Supermarkets have strict criteria for the cosmetic appearance of fresh fruit and vegetables. The result of these criteria is that a high percentage (10-40%) of a farmers harvest can be rejected because the vegetables do not meet these standard rules of conformity.

This problem of rejected vegetables was highlighted on a recent BBC programme ‘War on Waste‘

The programme highlighted a parsnip farm which was struggling to make a profit. Part of the problem was 40% of harvest was routinely rejected because it didn’t meet cosmetic specifications.

I have grown vegetables in the back-garden, and you realise how much diversity there is in different vegetable sizes. But, when you have grown them yourself, you would never think of throwing them away. In fact, you can become quite proud of different shapes (especially the amusing shapes, which I will not post on such a serious economics blog)

Photo Woodleywonderworks

Yet, if you go to a supermarket, many customers (perhaps sub-consciously) choose the most perfectly shaped vegetables. If you ask people if they would buy mis-shaped vegetables, nearly 100% of people would say they would. But, just because customers say the ‘would’ buy misshaped vegetables, doesn’t mean they actually will in practise.

Inefficiency of rejecting food

Nearly all the vegetables rejected are just the same on the inside. There is no difference in taste or nutrition, it is only outer superficial differences. To reject 20% of food grown is a waste of resources – increasing the costs of farmers, with a net welfare loss to society. Costs involved in rejecting food includes:

- Labour costs of sorting rejects

- Pesticides / fertiliser cost of growing food later discarded.

- Farmland used

All these factors associated with rejected foods have an opportunity cost. If you waste 20% of your land growing vegetables to be rejected, you could have used time and resources to grow other vegetables too.

Would customers choose to buy mis-shaped vegetables?

- The programme interviewed many potential customers about whether they would buy mis-shaped vegetables. 100% said they would. The programme also pointed out that in years of bad harvests, criteria are relaxed, and people keep buying the vegetables. In fact most people wouldn’t even notice.

- If this is the case, why do supermarkets have such rigorous criteria for rejecting food?

- The interesting experiment would be to have a pile of ‘perfect’ looking carrots and a pile of ‘imperfect’ looking carrots. I’m sure that given a choice between the two customers would choose the good looking ones, and leave the imperfect ones.

- It is rational for a customer to choose the ‘better looking’ vegetables. It’s a hard instinct to choose the uglier ones. Even if you know that essentially they are the same. Yet at the same time, the customer is being honest when they reply they would be happy to buy imperfect vegetables – they would if they have no choice.

How can supermarkets get around this problem?

- Selling mis-shaped veg at lower cost. Asda has announced a policy of selling mis-shaped vegetables at a lower price. It is called the wonky range. It is a good marketing strategy. But, there are costs involved in having separate sub-divisions for every type of vegetables. If all supermarkets had two options for different vegetables, there would be some higher costs involved.

- Relaxing criteria. Part of the problem is that the criteria seem unusually strict. Slightly relaxing criteria re: shape of vegetables would enable more veg to be sold, but not that much difference in shape.

- Educating customers. Campaigns to say mis-shaped vegetables are just as tasty. Interestingly the attraction of organic vegetables is that you get more realistic shapes. Customers feel organic food is higher quality because you don’t have too much interference and is closer to nature.

Problem of 40% increase in supply

You felt sorry for the parsnip farm which was struggling to stay afloat. The problem was that the price of parsnips (35p a kilo) was close to the average cost.

To the economist, this suggests the market is suffering from over-supply. The model of perfect competition suggests that if farmers are not making a profit, some firms will start to leave – reduce supply, increase price and make parsnips more profitable. It may sound harsh, but there are no easy solutions to over-supply – apart from reducing supply.

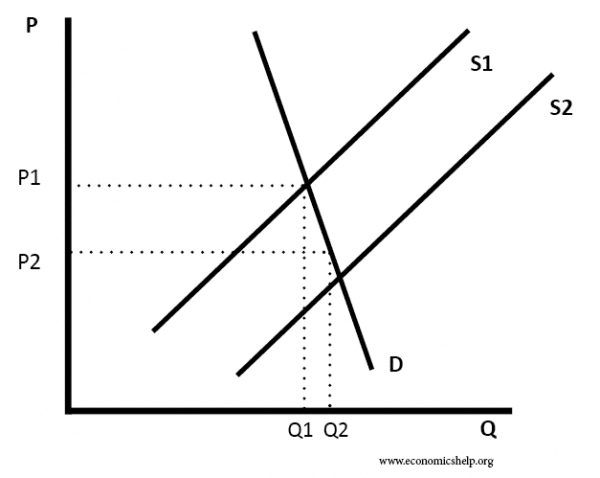

Suppose supermarkets overnight relaxed criteria and 40% more vegetables were released onto the market. What would happen?

Increase in supply with inelastic demand

- In the short run, the 40% increase in supply would depress prices (demand is quite inelastic)

- This would be actually bad for farmers in the short run – with inelastic demand, lower prices leads to even lower revenue.

- On the positive side, they would have lower average costs and may be able to sell more products. But, all farmers would see a fall in price due to the sudden increase in supply.

- In the long-run, it would still be good to change regulation. Because throwing away 40% of product is inefficient, leading to higher costs.

It does remind you of CAP – problem of excess food supply and then 40% of food stored and not sold to keep prices high. It’s not a good economic situation.

Three different issues

The important thing is that with the parsnip farm struggling to make a profit, there are three separate issues.

- Oversupply and low price in the parsnip market

- Issue of throwing away rejected vegetables

- Possibly monopsony power by supermarkets in setting low buying price from farmers.

Changing regulations on rejected vegetables, would not solve no. 1 and 2.

Conclusion

I like wonky vegetables, especially when I grow them myself. Yet, I’ve probably been guilty of unconsciously choosing better looking fruit and vegetables in a supermarket. Yet, even though I have definitely done it. I think it’s a big mistake that we place too much emphasis on cosmetic criteria.

I hope supermarkets relax the criteria, and I will do my part to buy vegetables even if they don’t meet my criteria for being perfect.

Related articles

i think is better to sell those misshaped veg at a low price than throwin them away…at least those farmers will receive something than nothing

Kenny, my response to your insight, based on my BTEC in economics, covers a wide range of vegetables.

A high minimum efficient scale, along with merger policy, should be implemented, rather than simply selling this ungodly veg.

The infrastructure should first be quantitatively eased.

Praise be to Tejvan

If the UK govt could contract out the fiscal policy to Microsoft, demand and supply would shift the privatisation in favour of the toothpick equilibrium as described by le Chatelier’s principle, solving the misshaped vegetable as well as the housing market; by proxy.

Of course this could all be avoided if we borrowed austerity from China and invested in Greek yoghurt.

Thank you for the article on the vegetable easing crisis, Tejvan.