The demand for money refers to how much assets individuals wish to hold in the form of money (as opposed to illiquid physical assets.) It is sometimes referred to as liquidity preference. The demand for money is related to income, interest rates and whether people prefer to hold cash(money) or illiquid assets like money.

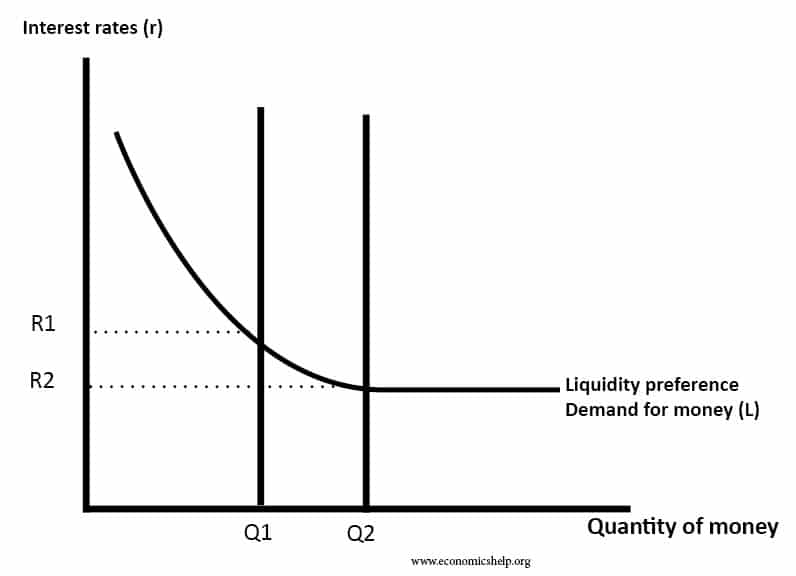

This shows that the demand for money is inversely related to the interest rate.

- At high-interest rates, people prefer to hold bonds (which give a high-interest payment).

- When interest rates fall, holding bonds gives a lower return so people prefer to hold cash.

Types of demand for money

- Transaction demand – money needed to buy goods – this is related to income.

- Precautionary demand – money needed for financial emergencies.

- Asset motive/speculative demand – when people wish to hold money rather than buy assets/bonds/risky investment.

Transaction demand for money

Transaction demand for money – the money we need to purchase goods and services in day to day life.

In the classical quantity theory of money. The demand for money is a function of prices and income (assuming the velocity of circulation is stable.) If income rises, demand for money will rise.

In an inventory model, the demand for holding money depends on the frequency of getting paid, and the cost of depositing money in a bank. When employees are paid, they will hold some money to buy goods. If they are paid once a month, they may deposit half to benefit from interest payments, and then withdraw after two months. However, electronic transfers and debit cards have made this less relevant.

Precautionary demand for money

- Precautionary demand for money – the money we may need for unexpected purchases or emergencies.

Asset motive

- The asset motive states that people demand money as a way to hold wealth. This may occur during periods of deflation or periods where investors expect bonds to fall in value.

Speculative demand

Keynes explained the asset motive through what he termed ‘speculative demand’. In this theory, he argued that demand for money is a choice between holding cash and buying bonds.

If interest rates are low, then people will tend to expect rising interest rates, and therefore a fall in the price of bonds. In this case, demand for holding wealth in the form of money will be higher.

If interest rates are high, and people expect interest rates to fall, then there is likely to be greater demand for buying bonds and less demand for holding money. If interest rates fall, then the price of bonds will rise.

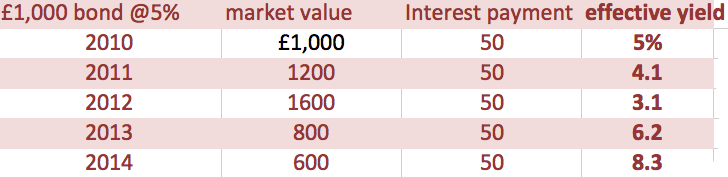

The inverse relationship between the price of bonds and bond yields.

Portfolio motive

The portfolio motive is another way of considering the asset motive. This theory was developed by James Tobin. He placed emphasis on the trade off between asset growth and risk aversion. For example, if an individual is nervous about future economic trends, he will hold money rather than purchase more risky bonds and shares. If the individual is optimistic, he will take risks and purchase fewer bonds and shares.

Evaluation how stable is demand for money?

The demand for money can vary due to many factors other than income and interest rates. These include

- Technological changes – e.g. debit cards, make holding cash less important. Easy access to current accounts can enable people to hold less cash.

- Availability of credit. If credit is more available, precautionary demand for money will fall as individuals feel they can borrow – if they meet short-term difficulties.

- Irrational behaviour of asset prices. Markets can enter boom and busts driven by psychological factors such as over-exuberance. In these bubble periods, demand for assets will rise and demand for holding money will fall.

- Empirical evidence in A Monetary History of the United States (1963) Friedman and Schwartz suggested a relationship between demand for money and income and interest rates. However, this relationship seems to break-down post-1975

- It depends on how you define money. Narrow definitions such as M0 and M1 are quite different from broader definitions. Also, there is near-money which includes short-term gilts with the maturity of fewer than six months.

- The demand for money can refer to narrow definitions of the money supply (M0, M1) or broad measures of the money supply like M3 or M4.

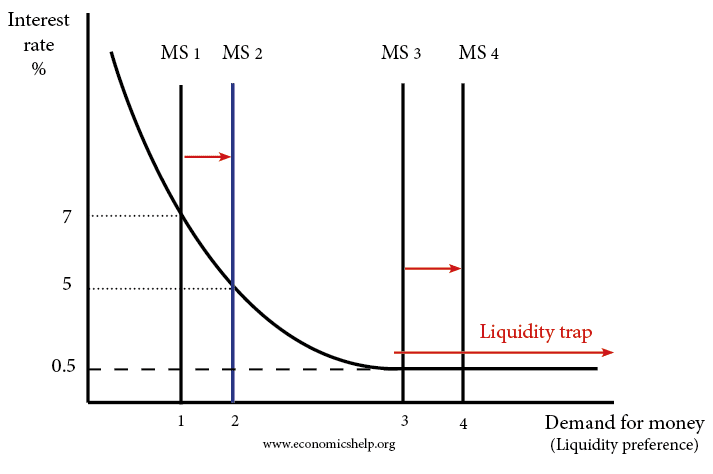

Money demand in a liquidity trap

In a liquidity trap, the demand for money is perfectly elastic. Increasing the money supply doesn’t reduce interest rates and the impact of increasing the money supply is ineffective in boosting demand.

Related