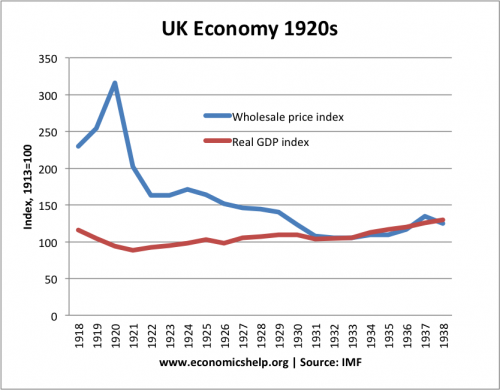

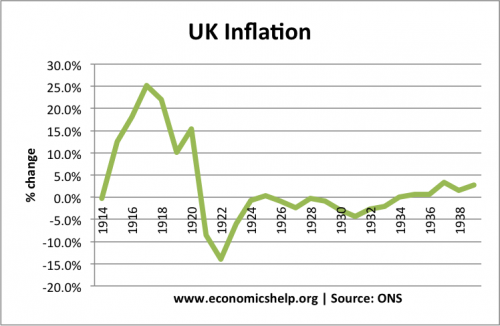

The 1920s are sometimes referred to as the ‘roaring twenties’, but for the UK economy, it was a period of depression, deflation and a steady decline in the UK’s former economic pre-eminence. In the US, the economy boomed on the back of mass production techniques, growing efficiency – and increasingly a credit bubble, which would later contribute to the stock market crash and the great depression. But the UK, tied to the gold standard, the economy experienced a decade of deflation and stagnant growth.

Mass Unemployment in the UK

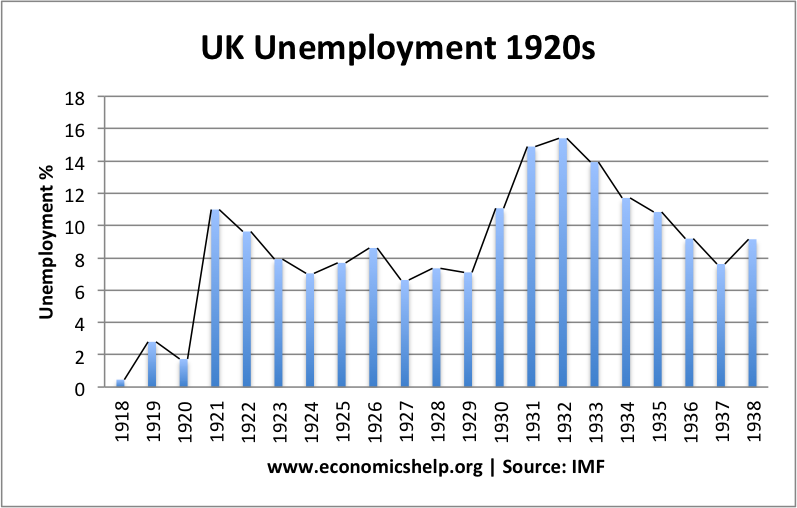

After the post-war boom of 1919-20 ended, UK unemployment rose sharply to over 10% and stayed high until the Second World War. The unemployment problem was particularly depressing for the many servicemen who returned from the Western front to find a lack of jobs on their return.

Reasons for Unemployment in the 1920s

- Lack of demand. Due to contractionary fiscal and monetary policy, there was insufficient demand in the UK economy, leading to stagnant economic growth.

- Efforts to keep Britain in the Gold Standard, and in particular, the decision in 1925 to return to the prewar level of $4.85. This meant UK exports were overvalued, and also monetary policy had to be kept tighter than necessary (real interest rates very high)

- Supply-side factors. Postwar, UK industries struggled to make the same productivity gains as competitors such as the US. British industries, which had performed well in the nineteenth century, such as cotton, steel, coal and iron faced difficulties from global oversupply and falling prices. There was a sluggishness in switching resources from these old industries to new growth industries like chemicals, rayon and motor cars. Other supply-side factors included a cut in the average working week and industrial unrest.

- Real Wage unemployment. Wholesale prices fell by 25 percent between 1921 and 1929. However, falling prices were not matched by falling wages, as understandably, the increasingly unionised labour movements resisted nominal wage cuts. This led to real wage unemployment.

- Deflation. Deflation discouraged consumer spending and increased the burden of debt. See: problems of deflation

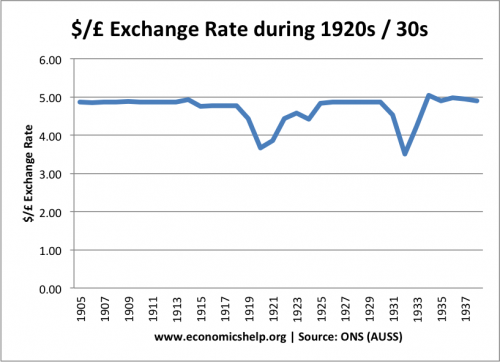

Gold Standard

A big feature of the UK economy in the 1920s was a desire to maintain the value of Sterling at its pre-war level of $4.86. This was partly a political move – the feeling a strong Pound was a key feature of Britain’s past economic success. During the war, Sterling had held its value relatively well – thanks to American loans. But, with the ending of the war and drying up of US loans, Sterling started to slide. The US dollar was becoming increasingly attractive due to:

- Rising US competitiveness

- Lower US inflation.

However, despite the weakness of the Pound, in 1925, Winston Churchill, as chancellor, returned the UK to its pre-war level.

To maintain the value of the £ at $4.85, it was necessary to pursue deflationary fiscal and monetary policy. (Higher interest rates to attract savings into the UK). Because US inflation was very low, this meant that the UK was effectively aiming for deflation. The attempt to keep the Pound in an overvalued fixed exchange rate was a key factor in contributing to deflation and lower economic growth.

Overvaluation of Pound

Keynes famously argued Sterling was overvalued by 10% compared to the dollar. Redmond (1984) argued the real effective exchange rates, between 1913 and 1925, for a variety of European countries meant Britain was overvalued by 5 to 10 percent for wholesale prices and by 15 to 20 percent in the case of retail prices

Deflationary Fiscal and Monetary Policy

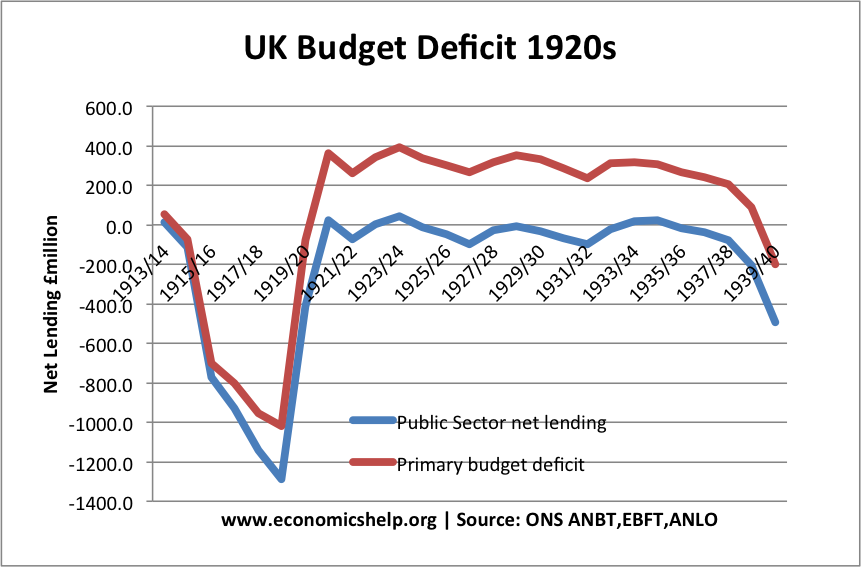

Between 1918 and 1920, government spending was cut by 75 percent. The government ran primary budget surpluses for most of the 1920s.

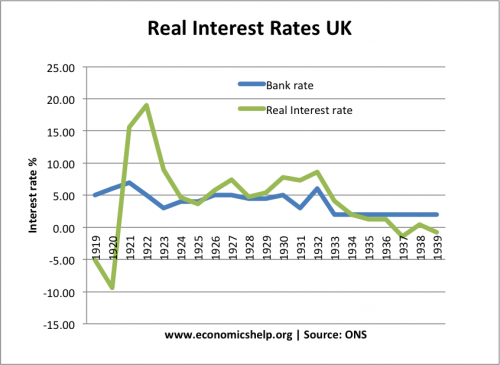

The Bank of England raised its discount rate from 5 to 6 percent in November 1919 and then to 7 percent in April 1920. Real interest rates remained high, throughout the 1920s, until Britain left the gold standard in 1931 and could cut interest rates. Higher interest rates reduced investment and spending. It also increased the cost of servicing Britain’s debt.

Compare this real interest rate, to the negative real interest rates of the 2000s.

Deflationary Fiscal Policy and National Debt

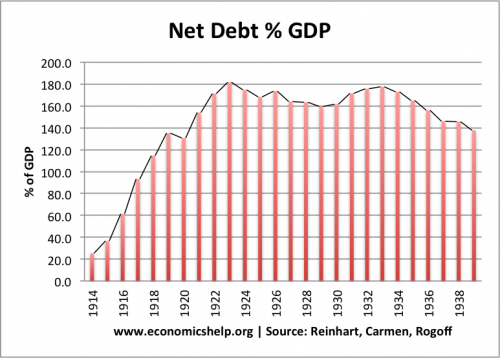

A sad fact about the 1920s was that despite the contractionary fiscal policy, the government failed to make a significant indent on the national debt as a % of GDP. Throughout the 1920s, the UK ran primary budget surpluses (excluding interest payments, tax revenue was greater than government spending). Yet, despite these efforts at fiscal austerity, national debt as a % of GDP was stubbornly high.

This has interesting parallels today (i.e EU austerity) because the UK experience shows that cutting spending during a deflationary recession (combined with tight monetary policy and fixed exchange rate) can be counterproductive to reducing debt burdens.

Very high debt levels, which were not solved by deflationary fiscal policy.

Industrial Policy

Post-1920, the UK experienced industrial stagnation. This was particularly marked in the UK coal industry. The declining industry led to lower wages and increasingly bitter trades disputes. In 1926, this culminated in a general strike. The miners went on strike for better pay and conditions, and were joined by some other trades unions. However, the general strike was only partial and led to the defeat of the miners. During the general strike, the middle class enthusiastically filled in for jobs helping to break the strike and increased a sense of class and social division.

Supply Side Policies in Economic Malaise

Labour productivity (1913-1950) rose by 59 percent in the UK. The United States and Canada did better (output per worker in these two countries rose by 77 percent and 67 percent),

In the early 1920s, when there was a 13 percent fall in the normal working week without any compensating adjustment in the weekly wage.

But, still faster than many countries such as Belgium, Denmark, France and Germany.

Source:

Related

I would like to know more about the return to the Gold standard and its relationship to the ‘cruiser crisis’

More about the Gold Standard here:

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/cabinetpapers/themes/economic-policy-1920s.htm