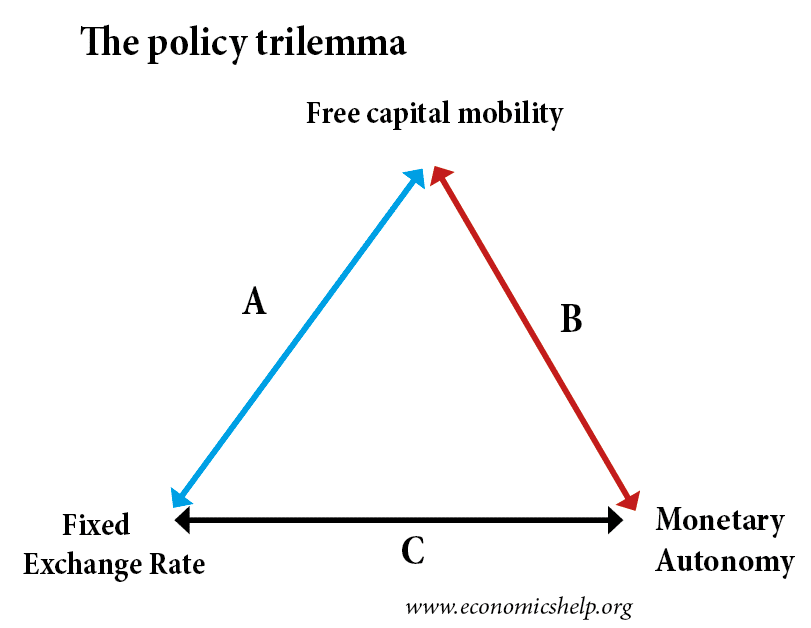

The policy trilemma refers to the trade-offs a government faces when deciding international monetary policy. In particular, the policy trilemma contends that it is not possible to have all three objectives at the same time, but has to choose two from the following three options:

- Free movement of capital

- Independent (autonomous) monetary policy

- Fixed (managed) exchange rates

Policy trilemma diagram

- A = Fixed exchange rate + free capital mobility

- B = Free capital mobility + monetary autonomy

- C = Fixed Exchange rate + monetary autonomy

Why the trilemma occurs

A = Fixed exchange rate + free capital mobility

If the government set a fixed exchange rate and allow the free movement of capital, then they will need to change interest rates according to outside pressures. For example, if the UK government wanted to keep the Pound fixed against the Euro, then the government would need to change interest rates similar to the ECB. If the market thought the Pound was overvalued, capital would flow out of UK into the Eurozone – putting downward pressure ont he Pound. Therefore, in response, the UK government would need to increase interest rates (and attract hot money flows) in order to maintain the value of the Pound and the fixed exchange rate peg.

- It means – in a recession, the UK could not cut interest rates because if it did, the Pound would fall in value.

B = Free capital mobility + monetary autonomy

If the government wished to purse monetary autonomy and it allowed free mobility of capital, it would need to allow a floating exchange rate. For example, if the government was worried about inflation, it could increase interest rates. These higher interest rates would cause appreciation in the currency. Countries which wished to promote growth would cut interest rates, but lower interest rates would cause hot money flows out of the economy and lead to a fall in the exchange rate

C = Fixed Exchange rate + monetary autonomy

If the government wished to have a fixed exchange rate but also change interest rates according to its own preferences, it would need to control the outflow of money. For example, suppose China wished to keep its exchange rate fixed but it wished to cut interest rates to boost growth. In this case, there is downward pressure on the Yuan. Investors wish to sell Chinese currency and buy dollars. However, if the Chinese government restrict capital flows. If it prevents the Chinese buying dollars and moving currency out of the country, then it can artificially keep the value of Yuan high.

Real world examples of policy trilemma

ERM crisis 1992

In 1992, the UK was in the exchange rate mechanism and trying to keep the value of the Pound fixed against the D-mark. However, during that time, there was free movement of capital. In 1992, markets felt the Pound was overvalued and so investors were selling Pounds – causing the value to fall. In response, the government increased interest rates (at one point up to 15%). But, this increase in interest rates was damaging to the economy (it caused a deep recession). Therefore, the UK government decided to give up on managing the exchange rate to regain control of monetary policy. They left ERM and interest rates were cut. This caused an economic recovery.

China

In period 2000-12, China wished to maintain relatively weak Yuan to boost exports and maintain strong economic growth. It also wishes to keep interest rates relatively low to maintain growth. To enable this combination, it has had to institute capital controls, which limit the amount of foreign currency Chinese nationals can buy. China would like to remove capital controls as part of moves to a more free-market situation, but from 2006-12 it was worried about excessive appreciation in Yuan – which is bad news for exporters.

In 2016, the Chinese again tried to loosen capital controls, but this time markets were concerned about the weakness of Chinese growth and the Yuan began to fall. This caused the government to re-strengthen capital controls.

Developing economies shadowing dollar

Many emerging markets seek to gain low inflation and economic stability by pegging currency against the dollar. It is a way for investors to gain confidence in investing and prevent inflationary pressures. However, once a developing economy pegs its currency against the dollar, it will need to give up freedom of capital or autonomous monetary policy.

- However, once a country has an exchange rate peg, interest rates will be set to achieve exchange rate target and not primarily for economic growth. It could mean (like the UK in 1992) that an emerging economy needs to increase interest rates, even in a downturn to keep the currency at its peg.

If a developing economy wanted to keep exchange rate peg and cut interest rates, it would need to prevent capital leaving the economy through capital controls.

Bretton Woods

The Bretton Woods system post war, involved most countries targetting their exchange rate to peg against the dollar. They also wished to maintain independent monetary policy. Therefore, in the post-war period, many countries used some form of capital controls. The breakdown of Bretton Woods was partly related to the increased difficulty of controlling capital flows.

Eurozone

In the Eurozone, countries have effectively locked into a fixed exchange rate, and also have committed to free movement of capital. This means countries in the Eurozone have to accept the loss of monetary policy. Interest rates are set by the ECB. There are even issues of whether Eurozone economies may need to give up autonomy of fiscal policy to maintain monetary union

Mundell Fleming model IS-LM- BoP

In 1962 and 1963, Mundell and Fleming presented papers which represented this policy trilemma in terms of an IS-LM-BoP trade-off.

Capital Mobility and Stabilization Policy under Fixed and Flexible Exchange Rates – R. A. Mundell The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science (JSTOR) Vol. 29, No. 4 (Nov. 1963), pp. 475-485

Evaluation

In practice, most fixed exchange rates rarely last. Countries invariably agree to devalue the currency if needed. In “Dilemma, not Trilemma: The Global Financial Cycle and Monetary Policy Independence” NBER 21162 Hélène Rey. (May 2015) argues the trilemma is effectively a dilemma between capital mobility and independent monetary policy.

– The difficulty of controlling capital. In theory, a government may wish to impose capital controls, but in practise, investors and individuals may seek ways around it. Also, once you impost capital controls, it may discourage investment and decrease confidence.

Related