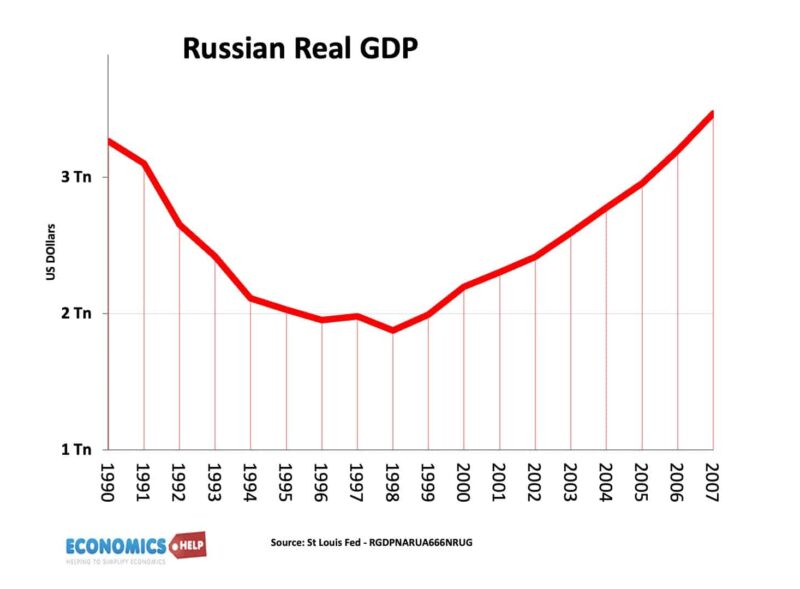

Between 1991 and 1998, Russian GDP fell an estimated 40%. The transition to a free market economy was plagued by hyperinflation, rising poverty, falling life expectancy and social dysfunction. Whilst the average citizen saw a marked deterioration in the quality of life, a few oligarchs became intensely rich as they bought state assets at a knockdown price.

In 2000, Vladimir Putin was first elected president. Helped by rising oil prices, the economy would grow 7% a year over the next decade. It seemed to ordinary citizens that the Russian economic nightmare was over and Putin would go on to enjoy persistent popularity.

Yet, in 2025, with falling oil prices, a plunging rouble, high interest rates and western sanctions, the Russian economy faces a new risk of crisis and stagflation. What happens to an economy can be more important than what happens on the battlefield.

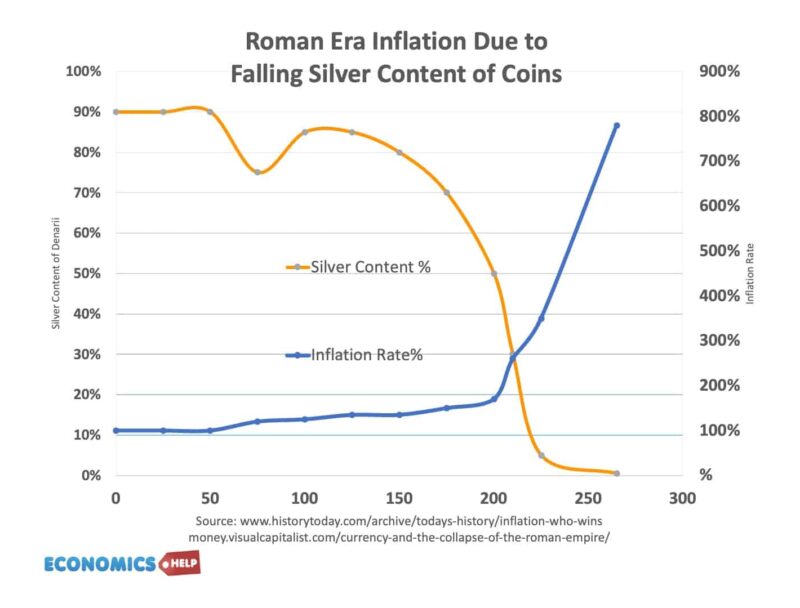

Ancient Rome Inflation

Nearly 2,000 years ago, the once mighty Roman Empire was starting to experience intense economic challenges. With trade declining, a succession of profligate emperors couldn’t fund their extravagant spending. With soldiers rebelling over a lack of pay, emperors started to print more coins by making it with less silver. As the amount of currency increased, prices rose, but it didn’t buy any more goods for the Roman soldier.

To deal with rising discontent, emperors just continued the debasement of the currency. By 220, the Denarius was worthless, just 0.5% silver and inflation was out of control. Soldiers on fixed incomes rebelled, stealing food from peasants, civil conflict escalated, and the emperors lost control. The Roman Empire would never recover.

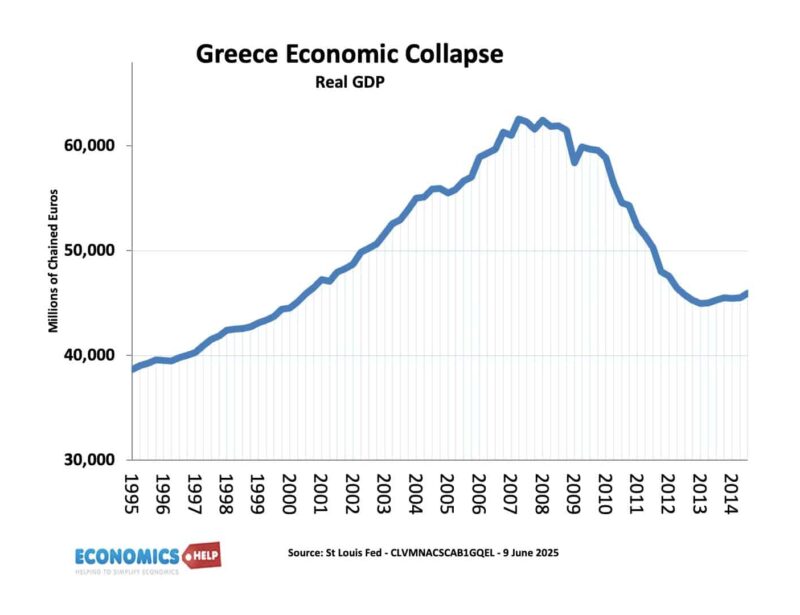

Modern Greek Decline

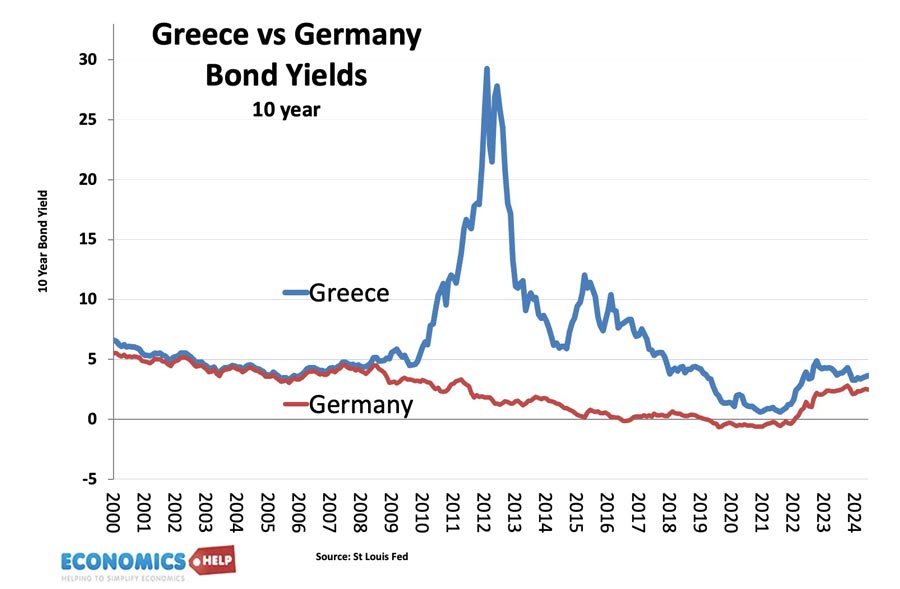

Fast forward 1,800 years, and it was modern Greece that would have one of the most dramatic collapses in modern history. After joining the Euro in 2000, the Greek economy boomed, but it was under false pretences. Greece was borrowing from European banks to fund domestic consumption. In 2008, the current account deficit was a spectacular 14% of GDP. But, in September 2008, Lehman Brothers went bust, and the bubble burst. For Greece, it was more devastating than anywhere else. German banks wanted some of their loans back, but Greece didn’t have it.

Bond markets had been happily buying up Greek debt like it was the safest asset in the world. But, the credit crunch and failure of credit rating agencies meant suddenly investors thought maybe buying greek debt when the government was insolvent wasn’t such a good idea. Bond yields surged to 30%. Not so much emerging market economy as a basket case economy. For all the talk of the Euro creating European unity, the reality was that German taxpayers didn’t see why they should bail out profligate Greek borrowing. The EU imposed painful austerity on the Greek economy. Taxes went up, spending was cut, but there was no outlet like a looseining of monetary policy or devaluation of an overvalued currency. Greece was in the Euro, and it couldn’t get out. The result was a bloodbath for the economy. GDP fell 30%, and unemployment rose to 28%. The rate for 15-24 year olds rose over 60%. Business closed and prospects seemed hopeless bleak. An estimated half a million Greeks left the country, causing a long-term decline in the working age population which is yet to be reversed. Greece was a good example of a self-reinforcing cycle of decline. As output fell, debt rose. As debt rose, the government imposed spending cuts. Spending cuts led to lower output. It was a cycle of despair. It could have been worse without some begrudging EU bailouts. They were never enough to end the cycle of austerity, but just enough to stave off complete bankruptcy. For all the talk of Greek economic collapse, recent years have proved more promising with debt coming down from a very high peak and the economy posting some of the most impressive growth figures in Europe. But, whilst the recovery is welcome, it is somewhat misleading. GDP is still 15% lower than 2008. The working age population has fallen by 12% and is still on a downward trend.

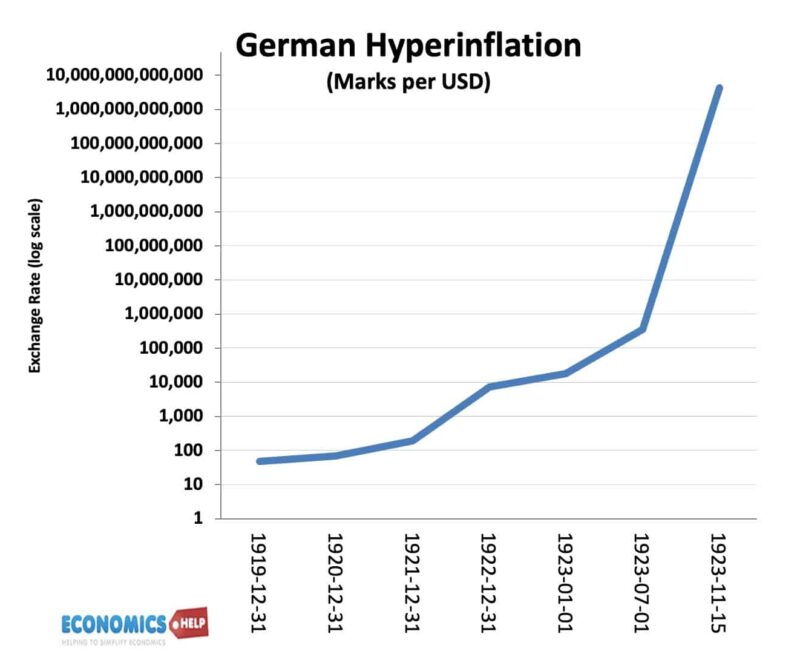

1922 Hyper Inflation Germany

In 1922, the German economy was buckling under the weight of post-war reconstruction and reparation payments. Similar to the Roman Empire, the government responded to worker discontent by printing money. It bought a few weeks’ respite, at least until workers realised the increase in wages was illusory, prices were rising faster, creating the pressure for only more money printing. Inflation soared, the German mark declined and the collapse in the currency created a real psychological shock. The middle classes who had saved for 50 years saw their pension value evaporate overnight. Money became worthless, people traded money for any tangible items be it buttons, paper clips or even string. The other impact of hyperinflation is that the collapse was not felt equally. Workers on fixed salaries and pensions lost everything, but those who owned assets, wealth and shares in companies were insulated. It was a psychological scar that Hitler would expertly exploit. You suffered, but they got richer –the calling card of every populist.

Great Depression

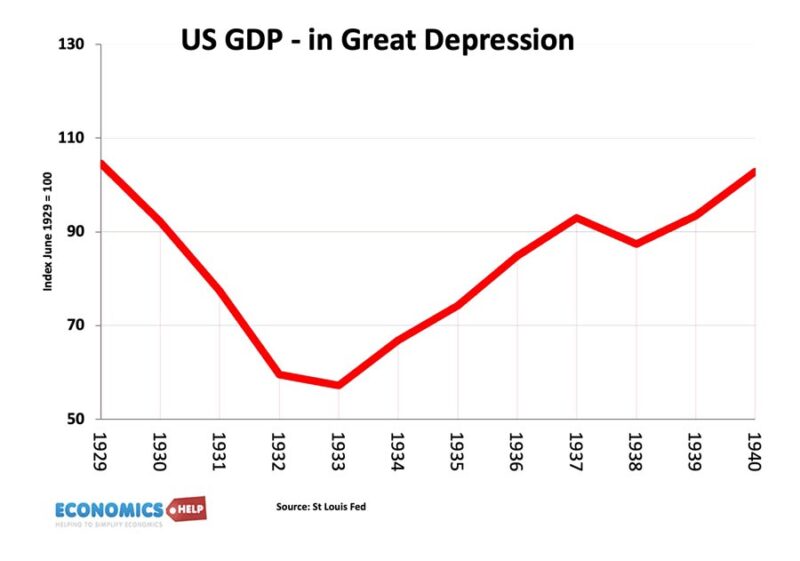

However, if hyperinflation sowed the seeds of Hitler’s rise, another economic collapse was needed to bring him to power. In 1929, the US stock market collapsed after years of a scarcely credible boom in share values. Investors had borrowed to get in on the act of rising prices. But, when sentiment turned, people lost everything and banks went bust. At first, the Wall Street crash affected only the 10% who owned shares. But, as banks went bankrupt and the government refused to intervene, the rot quickly spread. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon allegedly told Hoover, “Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate farmers, liquidate real estate. It will purge the rottenness out of the system.” Whether he said it or not is immaterial because that is what happened. 500 banks went bust, the money supply collapsed, wages fell, firms went bankrupt and GDP nosedived. Unemployment soared to 25%. The only real intervention in the Hoover years was a massive series of tariffs which caused a contraction in global trade. It created a whole generation of suffering at a time when government benefits were minimal or non-existent. The unemployed congregated in shacks outside cities, Hoovervilles desperate for the chance to work. On the positive side memories of the great depression were so vivid in the popular imagination that in 1945, there was a wave of support for creating a welfare system, an economy at full employment. Even war hero Winston Churchill would lose the 1945 election to Labour promising a welfare state.

In the US and UK, the great depression didn’t lead to political extremism, but back in Germany, with unemployment reaching 6 million, Hitler’s message of national renewal had a whole new constituency of the despairing and angry. One of the painful ironies of history is that Hitler’s remilitarisation of Germany and willingness to spend was actually pretty successful in reducing unemployment and revitalising the economy. A reminder that even when economies collapse under the weight of mass unemployment, it doesn’t have to be like this. Under Roosevelt, American dabbled with the new Keynesian ideas, some public works schemes did create employment. But the shadow of the depression never really left until 1940.

Venezuela

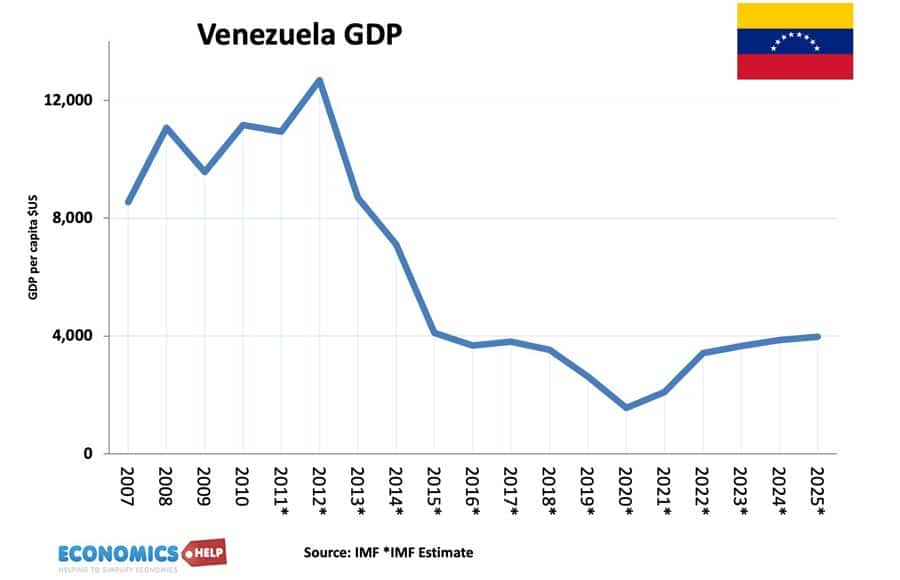

In the 1970s, Venezuela was widely admired for its functional democracy and the highest living standards in Latin America. There were good reasons to be optimistic. It has the world’s largest reserves of oil in the world. Yet, within the space of 8 years, the economy lost nearly 70% of its output in one of the most spectacular collapses of the modern era.

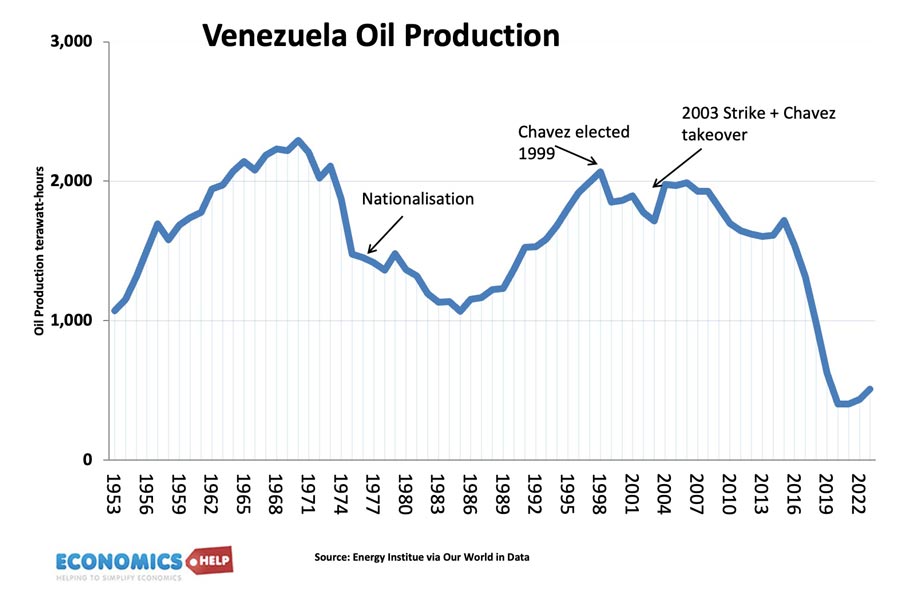

When Hugo Chavez was elected president in 1999, Venezuela was producing 2,000 terrawatt hours of oil. By 2020, this had fallen to 300. To retain popularity, the government funded generous welfare programmes. But, with falling oil prices, rampant corruption, crippling US santions and falling oil output, the income just wasn’t there. With social discontent rising, the government printed money to keep welfare programmes going, but this caused the inevitable inflation. Foreign investment fled, and so did Venezuelans. Between 1999 and 2019, an estimated four to six million of the best educated Venezuelans fled the country, nearly 20% of the whole population.

United States

Venezuela, Zimbabwe and Argentina have had spectacular collapses, but they don’t affect the global economy. But, the United States is a different matter. In 1929, the US economy was around 29% of global GDP, the US depression spread to nearly the entire world, because the knock-on effects of lower trade, decline in confidence and lower demand were felt everywhere. In 2008, the US accounted for 26% of global GDP, but an outsize influence on finance. A housing collapse largely focused on Flordia triggered a world wide financial crisis and recession. Global banks had been buying US debt, not entirely aware of what they were buying. The liquidity crunch led to banks going bust from Iceland to the UK. The effect on global growth was immediate, with GDP falling, unemployment rising and the hangover of the crisis leading to a period of austerity and growing instability.

The one bright side of the 2008 financial crisis is that, unlike 1929, government intervention was more decisive in preventing a full blown bank crisis. A massive injection of money kept the financial system afloat. But, arguable created winners and losers. The winners were the banks who had precipitated the crisis, the losers were the taxpayers who funded the bailout and largely faced a decade of lost growth and austerity.

Capacity of Renewal

However, I want to finish on a positive note. Arguably, the greatest economic collapse of the last century was the state of the German and Japanese economies in 1945. In Germany, infrastructure, industry and confidence was utterly destroyed; they had lost seven million lives. Yet, slowly at first, quicker later, the economies recovered and by the 1960’s people were talking of the German economic miracle, like a phoenix rising from the flames, is testament to the capacity of economies to recover and reinvent. Germany’s recovery was aided by the Marshall Plan and the relatively enlightened attitude in victory compared to 1919. But, to go from utterly defeated to economic superpower in a few decades is testamony to the capacity of economies to recover.

https://money.visualcapitalist.com/currency-and-the-collapse-of-the-roman-empire/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-45207092