In 1976, the minority Labour UK government of James Callaghan was ‘forced’ to borrow $3.9 billion from the IMF to stabilise the value of Pound. The loan was also accompanied with conditions to cut public spending and raise interest rates. It marked a symbolic break with the post-war economic consensus and was a reflection of persistent problems in the post-war UK economy. After the bailout, economic conditions turned around with an improvement in the current account, budget deficit and appreciation in Sterling. But, fundamental weaknesses remained with high inflation and a winter of discontent (1978/79) causing further instability.

Backdrop to the crisis of 1976

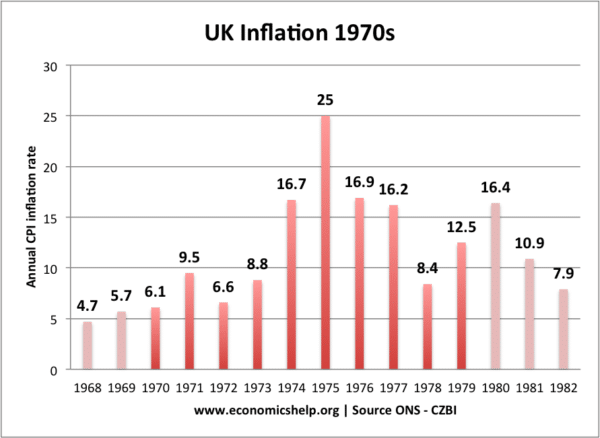

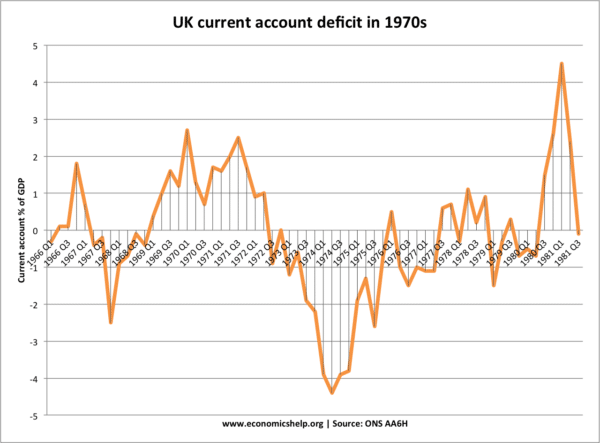

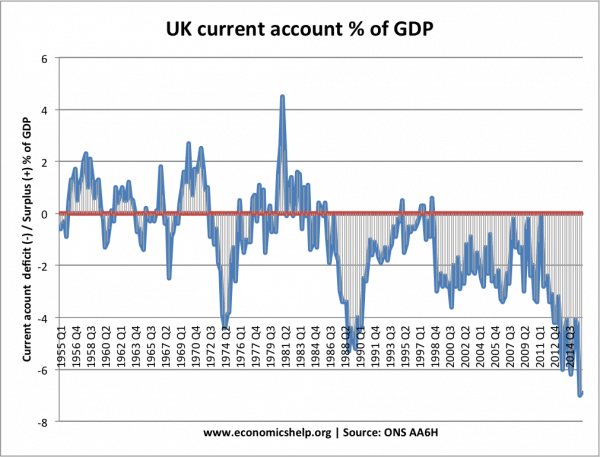

The crisis occurred against a backdrop of high inflation, the 1974 recession, oil crisis, high levels of government borrowing and a current account deficit. The weak UK economic picture had been putting downward pressure on the value of Sterling.

In 1974 the National Institute for Economic & Social Research made a report about the UK economy. Its conclusions made grim reading:

“It is not often that a government finds itself confronted with a possibility of a simultaneous failure to achieve all four main policy objectives: adequate economic growth, full employment, a satisfactory balance of payments, and reasonable, stable prices.” (Gresham Lecture)

The report could have added two further macroeconomic objectives in peril – a manageable budget deficit and stable Pound.

Given a growing budget deficit, in early 1976, James Callaghan proposed a white paper to cut the budget deficit, but it split the Labour cabinet with left-wing ministers like Michael Foot opposing the spending cuts.

Sterling

In the post-war Bretton Woods era, governments did not fully believe in floating exchange rates but targeted a ‘managed exchange rate’ – fearing a depreciation from their target would cause economic instability and problems such as more inflation. If the government had followed a floating exchange rate and not tried to intervene in the Sterling markets, the need for the loan would have been significantly less and probably not needed.

High inflation, a current account deficit, a weak export sector and economic uncertainty were all putting downward pressure on the value of Sterling. Between 1972 and 1976, Sterling depreciated 20%. The depreciation in the value of Sterling was welcomed by some in the Treasury who saw the depreciation as a way to restore competitiveness and reduce the current account deficit. But, the government retained an unofficial policy of trying to stabilise the currency – fearing among other things – continued depreciation would worsen the double-digit inflation.

It was the fall in Sterling which caused the government to approach the IMF for a bailout (with lesser concerns about government debt)

IMF Bailout

Investors felt the Pound was overvalued so started selling

IMF agreed to aa loan of $3.9 billion in September 1976, which was mostly used to repay Central Banks which had been offering loans to support the value of the Pound.

The IMF bailout was given under conditions of higher interest rates and cutting government spending to reduce the PSBR (budget deficit as it was called then)

Post Bailout

After the bailout, the UK economy recovered with stronger growth, growing oil revenues, an improved current account and appreciation in the value of the Pound. Even the budget deficit turned out lower than expected. The full loan was not taken out and loan was soon repaid.

“[an economist was] a man who, when you ask him for a telephone number, gives you an estimate”. Gresham Lecture

However, the crisis crystalised a new direction in UK economic policy; it was seen as the fading away of the old “Keynesian” post-war consensus and signalled a greater priority for targeting inflation, and deflating the economy if necessary.

Also, although the economy recovered, it still struggled with high inflation, poor industrial relations and (by post-war standards) high unemployment.

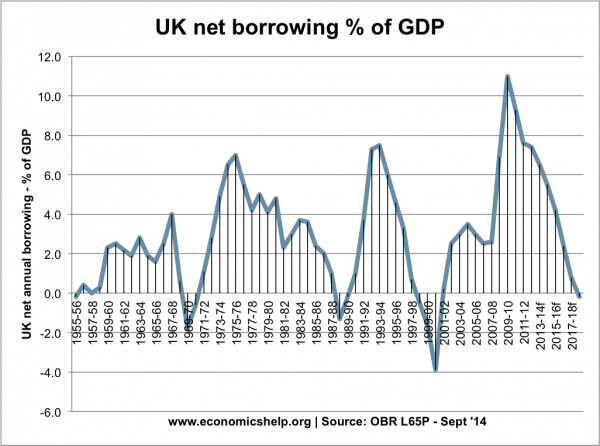

Budget deficit

The recession of 1974 caused a rise in the UK budget deficit to a record post-war level; the recession caused unemployment and a fall in tax revenues.

Interesting points about IMF Crisis 1976 – compared to current situation

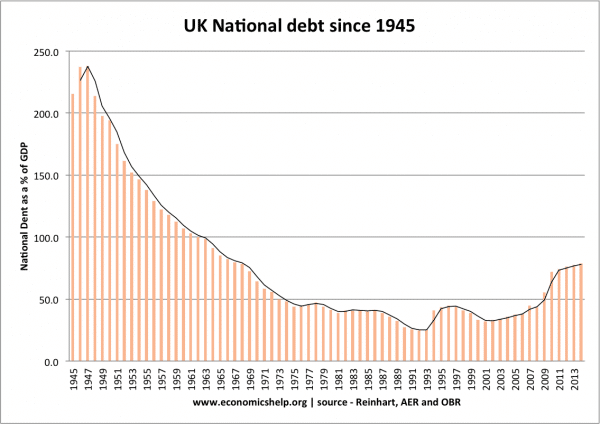

Government borrowing was relatively low by 2011 standards. At 7% of GDP, in 1976, the budget deficit was large, but less than the 11% seen in 2011/12. In the mid-1970s, the National debt had been steadily falling since 1945. In 1976 was less than 50% of GDP – half that of 15 years previous.

However, the presence of high and variable inflation meant investors were more reluctant to buy government debt. In 2010-16, growing debt corresponded with falling bond yields because we were in a low inflationary environment.

Managed exchange rates

A key contrast of the 1970s was the focus attached on managing the exchange rate. Ironically, after fears over devaluation in 1976, the Pound appreciated to a high of £1 to $2.5 by 1981 causing a recession – especially in export industries.

Devaluation of 1992. The 1976 crisis has some parallels with 1992 when the UK was trying (and failing) to maintain the exchange rate in the ERM. The government used foreign exchange reserves to try and keep value Pound within its target. Unlike 1976, they were also deflating the economy with very high-interest rates.

Related page

External pages

- IMF Crisis – Mainly Macro

- IMF Crisis 1976 – Richard Roberts at Amazon

- IMF Loan – at National Archives

Inflation is caused by government printing cash to make up for over spending. This is not mentioned or the reasons why spending was high and was not cut. This would help in understanding why and how the crisis got so bad due to political pressures on the government who must have been under pressure to make no cuts despite an income crash.

“Inflation is caused by government printing cash to make up for over spending.”

Actually that is not mentioned because it is not true. ‘Printing cash’ was exactly what QE was on a far greater scale than what was done done in 1976. It created no inflation.

And government spending creates cash. As anyone who knows basic macroeconomics will tell you. Some might argue that that spending should be offset by issuing government bonds. But not even that is actually necessary. It could simply be carried as a deficit like QE is.

The real cause of inflation is a bit more complex than you think.

This aged well.

And this is exactly what Corbyn is proposing to do now. Borrow billions and billions to nationalise water energy and rail and take private contractors out of all public services including the NHS. It could be much more than $500bn will be needed and they say it will all be borrowed so will lead to massive inflation.

You have twice above claimed Corbyn intends to borrow. Yet his last manifesto contained no such claim. Nor has he said that since. The Tories however made no such claim either but have increased their estimates of their own borrowing plans several times since.

I am afraid facts speak louder than words. Especially when those words were never spoken.

Corbyn’s plans for nationaling our major industries, would not be possible without major borrowing. Labour always makes inflated claims. Gordon Brown gave deadlines for medical operations and treatments. This resulted in my dad, having his new knees done in a private hospital. The NHS just didn’t have the funds, so, Labour went to the private sector for funding. I always congratulate Labour, for being the party who put the NHS into private hands!

Sidney Cordle is correct. As one of those who lived through those times knows. I was in the Army and the only way to increase income to pay the increased interest rates was to get moon lighting jobs.

We had the ludicrous situation that servicemen could claim benefit as they did not receive a living wage from HM govt, it was a rough time.

I lived through those times too. But my memories are different. For example I remember the ending of Bretton Woods and the subsequent removal of exchange controls creating massive volatility in sterling and balance of trade figures. And then YOM Kippur and the OPEC response to quadruple oil prices. I rather think those events had more influence on this crisis than anything else.

So I won’t blame the economic and industrial mess Labour inherited in 1974 solely on Ted Heath but in a sense he was lucky to get out when he did. Things were only going to get worse whoever was in power.

If you disagree then answer this question. If it was right and necessary that Callaghan went to the IMF in 1976 when our current account deficit was 4.5% of GDP how come It was not necessary for Thatcher between 1988 and 1992 when it was nearer 5.5% and UK net borrowing was nearly 8%?

The situation then is often represented by people who do not understand economics as a unique event – caused by Labour mismanagement. But the sudden increase in FOREX trading which occurred then was not created by Labour and was not a transient phenomenon. It did not subside but has grown into the biggest market in the world. Some would say the biggest gambling venue in the world.

Cost-push inflation is like the other side of the productivity coin and it’s complicated for the same reasons. When it comes to sharing productivity gains you have a big tasty pie that labor and capital fight over to see who gets the biggest share. Fortunately it only lends itself to mild inflation as everyone likes pie and the pie is growing.

With cost-push inflation you have labor and capital fighting to see who has to take the biggest bite of a shit sandwich. Something exogenous like the energy shocks of the 70s comes along to diminish real incomes and nobody wants to take the hit. There’s no straightforward fiscal or monetary policy answer to that problem. The more evenly matched the sides, the longer the tussle can drag out and the more inflation can result as both sides scream “You eat it!” “No, you eat it!” with rounds of wage and price increases.

A proper resolution really reaches broadly into labor, wage and price policy and, yeah, it’s complicated.

On the subject of “borrowing” only the truly feeble minded believe that monetarily sovereign governments borrow money from the private sector.

If you have a printing press, would you borrow money?

The government will let you deposit money at their central bank. It is not used, it is not spent.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Government_debt

“government debt held in the home currency are merely savings accounts held at the central bank. In this way this “debt” has a very different meaning to the debt acquired by households who are restricted by their income. Monetarily sovereign governments issue their own currencies and do not need this income to finance spending.”

What was that last part again?

“Monetarily sovereign governments issue their own currencies and do not need this income to finance spending.”

and for the avoidance of doubt:

“do not need this income to finance spending.”

Labour mismanagement or the quadrupling of oil prices? Sounds a bit like the worldwide recession of 2008 becoming ‘Labours recession’ every time a Tory opened their mouth.

So three years after joining the EEC we were so deep in the doo-doo that we had to borrow from the IMF. And our subsequent recovery was down to de-regulation and North Sea oil revenues. And employment levels have only just recovered to pre 1973 levels. Or am I missing something