A big issue is how net migration is affecting the National Health Service.

- Does an influx of migrants place greater strain on the NHS?

- Is migration a convenient excuse for the more long-term issues facing the NHS?

- To what extent do migrants work for the NHS?

- If we cut migration levels would that affect taxation and spending on the NHS?

National Heath Care under pressure

The first factor in determining the health of the National Health Care system is how many resources are put into it.

The government has often stated that it has ‘ringfenced NHS’ spending. This is to reinforce the notion that there has been no real spending cuts to the NHS. This is true, real spending on the NHS has risen consistently. See: UK Health care spending.

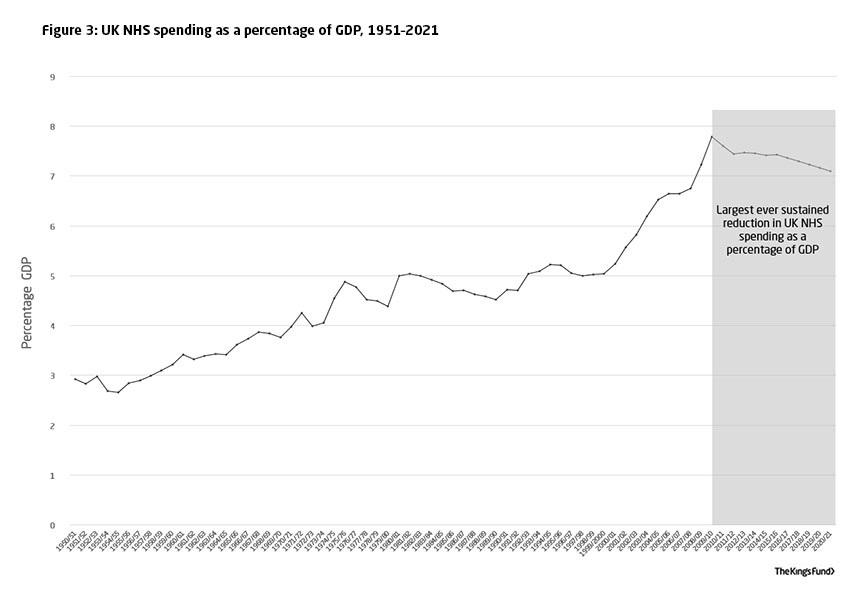

However, as a share of GDP, spending on the NHS has been falling since 2010 and is set to forecast to continue to fall.

Also, it’s easy to increase spending on the NHS when you have a rising population (partly caused by immigration). A more useful statistics to real spending is real spending per head.

In the post-war period, spending on the NHS as a share of GDP grew rapidly because

- Increased technology enables more treatment

- People live longer, needing more treatment.

- Expectations about the NHS have grown

- People consistently place NHS as one of most important areas of government spending

Because of all the increased potential treatments, if you start cutting NHS spending as a share of GDP, you start to get increased pressure, waiting lists and perceived inadequate resources.

It is this cut in the share of resources devoted to health care that is placing pressure on the NHS. Especially when you combine with an ageing population, which is placing more demands on health care.

When you’re stuck in a waiting list, it is tempting to blame the influx of migrants. However, if cut immigration to zero, it wouldn’t alter the trend in government spending on health care.

Fiscal contribution / cost of migrants

Generally, migrants are more likely to be young – 20s to mid 30s is the most common age.

One study found the average age of migrants from Eastern Europe (EEA10) was 26. This compares with an average age of 41 for UK born citizens. Link

Another study found nearly 34% of foreign-born workers were aged between 25 and 35 years old, while nearly 22% of UK-born workers were in that age group. (UK Labour Market – Migration Observatory)

As people get older, migrants often return to country of origin. This age range (20-30s) is the best demographic for contributing taxes, but not using health care services. Health care services are much more likely to be used by people over 65.

Fiscal Contribution of migrants

One study by Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration UCL ‘Fiscal Effects of Immigration to UK found

“The positive net fiscal contribution of recent migrants since 2000 from the east European accession states, including Poland, amounts to £5bn; those from the rest of the EU, including western and southern Europe, have contributed £15bn, and those from outside Europe more than £5bn… Whereas EEA immigrants have made an overall positive fiscal contribution to the UK, the net fiscal balance of non-EEA immigrants is negative, as it is for natives. If this is true, cutting immigration will lead to budget shortfalls, which will need to be met by spending cuts, tax rises.”

NHS staff and migration

55,000 out of the 1.2 million staff in the English NHS are citizens of other EU countries. (Full Fact) The UK has long relied on a relatively high percentage of doctors and nurses from abroad. In recent years, the numbers of NHS staff from Europe has increased.

Another study shows 11% of all staff and 26% of doctors are non-British. (link)

Leaving the EU would enable the UK to restrict migration from Europe, although, equally, a new migration policy could still enable migration of skilled workers such as nurses and doctors.

Cost savings from leaving the EU

Some argue that since the UK is a net contributor to the UK, if we leave, this money can be used to spend on the NHS. However, this cost saving of £9.9 net (according to ONS) has to be weighed against the potential fall in GDP / rates of economic growth from leaving the single market and decline in trade and inward investment which would affect tax revenue.

National health service vs housing

In a post on migration on housing, there is a good case to say high levels of migration are exacerbating the housing crisis. The difference is that there is a fundamental reluctance to build new houses in the UK, therefore a rising population is increasing the gap between demand and supply. However, the NHS is different, migrants are more likely to contribute towards the exchequer and, because of their relative younger age have low demand for health care. Ending migration from Eastern Europe would do nothing to deal with the long-term stresses on the NHS.

Conclusion

When people say immigration “exacerbates our housing crisis and puts pressure on our public services”. I only agree with the first part of the sentence. Yes it causes problems for housing market, but without immigration the UK fiscal position would be worse.

The National Health Service is stretched primarily because of rising demand from demographic changes combined with the growth of new (expensive) technology. At the same time, the cut in spending on the NHS as a percentage of GDP is limiting capacity to keep up with demand.

The influx of migration on the NHS is, according to studies above, not placing any greater strain on the NHS. Migrants of young working age tend to have a net contribution of public services. The NHS is also reliant on foreign staff to fill the gap in UK trained medical staff. Though in theory, a post Brexit immigration policy could enable migration for any medical staff.

related