- The Government doesn’t actually print that much money

The Bank of England is notionally independent, but heavily regulated by the government. Have you ever wondered how much physical cash the Bank of England printed last year?

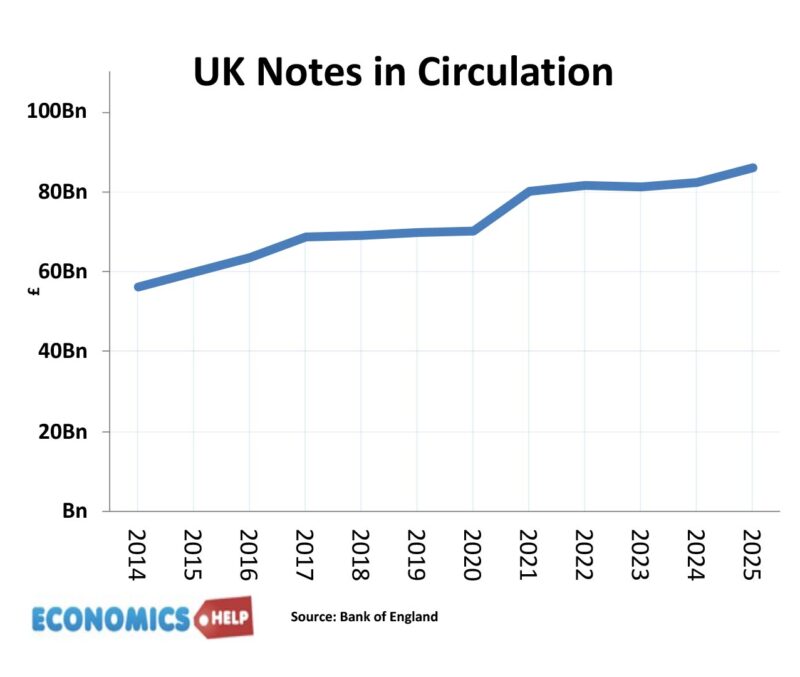

The net amount of notes in circulation increased from £83bn to £84bn, a tiny fraction of the total money supply. Now when people talk about the government printing money, they are probably referring to the modern day equivalent of Central Bank creating money out of thin air under quantitative easing to buy bonds from banks. But, is this actually like printing money? Not really. The Bank of England created nearly £900bn of electronic money between 2009 and 2020. The Fed in US created $6.8 trillion. This led to a massive increase in the monetary base; commercial banks had more money with the central bank, the excess reserves of commercial banks soared, but the impact on the actual broader money supply was much more muted. When QE started, there was a small increase in M4 money supply, but the link between the two is weak. Early versions of QE caused very little, if any, inflation. It wasn’t until 2022 inflation happened; we’ll return to this later. But, also, since 2022, the Bank of England have started to reverse QE, actually taking money out of the monetary base. Has this caused falling money supply, deflation and falling house prices? No

- It’s commercial banks which create most of the money

In a modern economy, commercial banks create 90-95% of the new money supply. When they lend you £200,000 to buy a mortgage, the bank literally create an electronic deposit in your bank account. Suddenly, there is £200,000 more money supply. A Central Bank can try and influence a commercial banks indirectly, through interest rates, bank regulations and quantitative easing. For example, deregulation of bank lending, can lead to an increase in money supply because banks are more willing to lend bigger mortgages. Recently a bank introduced a 100% mortgage, that is kind of thing that can increase the money supply.

By the way the government could more directly increase the money supply, if they wanted to. Rather than quantitative easing, they could create money electronically and give it directly to households and business. There is a concept called helicopter drop. When the government literally creates money and figuratively drops it from the sky, that would definitely increase the money supply.

- Trade deficits are not necessarily bad.

Before Adam Smith, the dominant economic ideology was mercantilism, the idea that you should seek to gain a trade surplus – accumulate gold and silver, and this would make you better off. It was kind of a justification for colonialism, the only way to get richer was to take wealth off other people. Perhaps this world view is making a comeback. But the real benefit of trade is that it allows you to import more goods. Imagine Saudi Arabia exported lots of oil and made huge trade surplus, which doesn’t actually increase living standards, but when you buy goods from abroad you start to be better off.

Trade deficits can definitely be bad. In 2011, The Greek current account deficit was running at 11% of GDP, the exchange rate was overvalued, they couldn’t devalue and Greek consumers were borrowing from German banks to import German cars, that’s a slight simplication but fiancing a trade deficit by borrowing when you are uncompetitive is a recipe for disaster.

But, if we take the example of the US it is seen, or at least used to be seen, as an attractive place for inward investment, and buying US assets like bonds. So the US has a capital surplus which finances the current account deficit. The US is getting the best of both worlds, enjoying more imports, but also seeing capital inflows which help to reduce bond yields on borrowing. It is ironic that efforts to reduce US trade deficit with tariffs is causing investors to sell US assets, causing rising bond yields. The important thing is that the trade deficit /current account deficit is only one part of the balance of payments. For 70 years 1800 to 1870, the US ran a trade deficit because it was attracting capital inflows, e.g. British banks investing in building US railroads. From 1870 to 1970, the US was a manufacturing powerhouse, and it had a trade surplus.

- Inflation good – deflation bad?

If inflation is bad, does that make deflation good? Well, the only thing worse than inflation is deflation. When prices fall, how can that be bad? Several reasons. Firstly, in a period of deflation, it’s not just downward pressure on prices, but downward pressure on wages. If you have debts, deflation makes it harder to pay them off. You can find yourself paying a larger share of wages on mortgage or loan repayments, leading to less income. When prices fell in Japan in 2000s, consumers became very reluctant to buy expensive products, because they always thought it would be cheaper in the future. Japan’s period of deflation and ultra-low inflation led to very low growth and a big rise in government debt as a share of GDP. The Japanese tried desperately to end deflation, but found it surprisingly difficult. Deflation can also lead to higher unemployment as falling prices and falling revenues mean firms can’t afford labour. The UK had a long period of deflation in the 1920s and 1930s, partly related to joining the gold standard at the wrong rate, but it was a disaster for the economy. Wages were cut, precipitating the general strike of 1926, and unemployment was persistently high.

- Government influence on the economy is usually limited

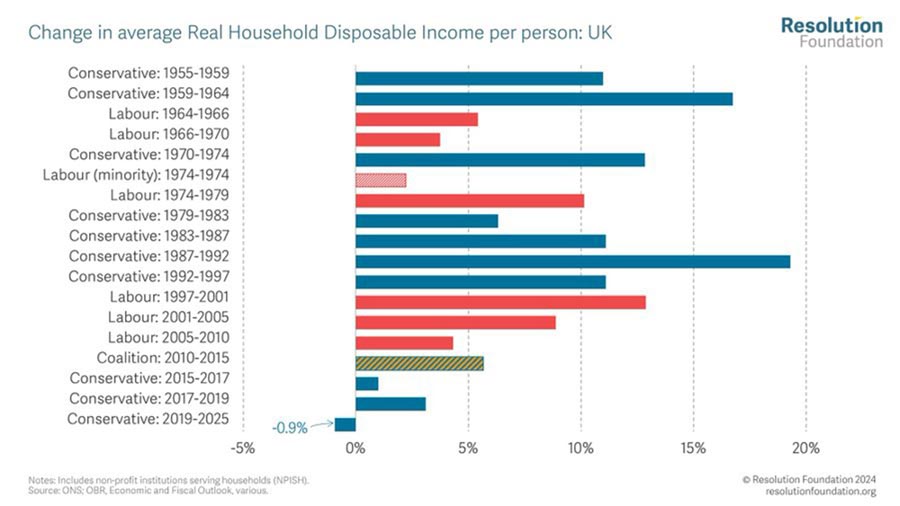

When things go wrong, we tend to blame the government, and there are often good reasons. But, it is often the case, governments are at the mercy of events more than we give credit. In 2022, inflation hit all advanced economies, whether they promoted economic stimulus or not. US stimulus and loose monetary policy did contribute to US inflation of 2022. But, countries without stimulus had very similar inflation rates. Nearly all incumbent governments standing in 2024 lost because economic fundamentals were bad across the world. This isn’t to say governments can’t be consequential. Very high tariffs will impact consumers, austerity can slow economic growth, and governments can cause inflation by overheating the economy. The Barber Boom, the Lawson boom were both cases of government causing inflation by rapid economic growth. But, 2022 inflation was a global phenomenon.

6. Lump of Labour Fallacy

Some argue if you allow immigrants into country, then this will cause unemployment and falling wages. But, if immigrants enter a country, the economy expands, jobs are created, and the number of jobs increased. At the turn of the century, the US population exploded due to immigration, it was still a time of rising real wages and unemployment stayed low. However, that doesn’t mean net migration will necessarily increase GDP per capita. If you double the population, GDP doubles, but ceteris paribus, GDP per capita will stay the same. It depends if migrants can improve productivity, e.g. technological innovations of US immigrant scientists like Einstein, Tesla and Enrico Fermi.

7. Technology will make us all unemployed.

New spinning machines made skilled weavers unemployed, so they smashed up machines hoping it would save their jobs. But, in the long-term, new technology moves jobs around. Once 90% of the population worked on the farm, technology caused job losses on farms, but over time created better ones in manufacturing then services. In 1920, the UK had 1 million coal miners; technology has destroyed all these jobs, but is the economy worse off as a result? I’d rather be making videos about economics than shovelling coal up in Yorkshire. That doesn’t mean that technology can’t cause real economic hardship, though. The transition to new jobs, can be very difficult for those affected, e.g. coal miners lacking skills to work in new jobs. Will AI make us all unemployed, well I hope not, but the impact could still be a lot of uncertainty.

8. No simple solution

Be wary of people who confidently give very simple answers to complex questions. Are all inflation and economic problems because we left the gold standard? Can we solve all our problems by printing money? Everything mentioned here is still a simplified version to make it palatable; you could spend hours teasing out the nuance and different aspects of this question. Often it just depends on the economy situation. In the 2010s, I would argue austerity was damaging economically, but it doesn’t mean that cutting government spending would always slow down economic growth. Canada cut spending in the 1990s, and had a stronger economy, but it depends so much on what else is happening. Do these videos ever change your mind? I sometimes learn things making them. I used to be a big fan of solar power just because I like the idea of clean energy, but after researching energy prices, I realised solar is only as good as storage and grid’s ability to distribute the energy.