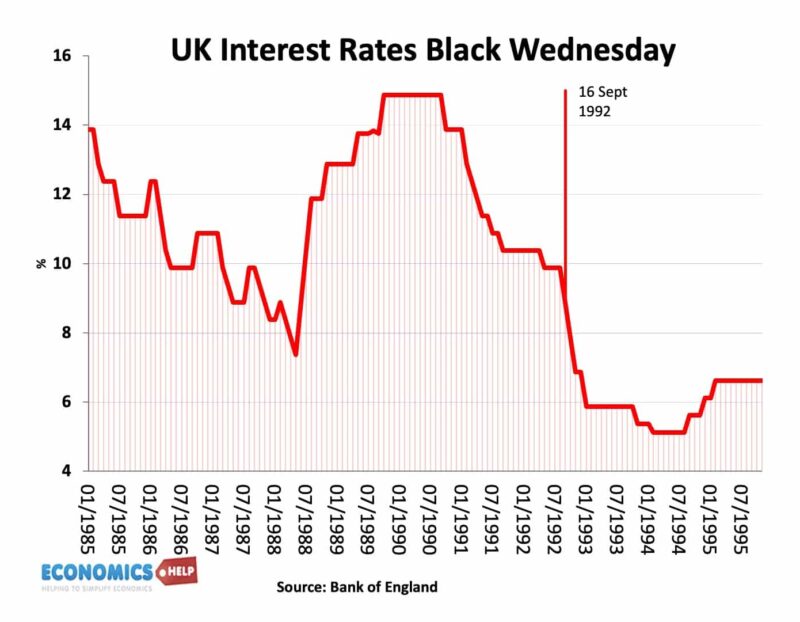

On Wednesday 16 September 1992, the UK economy was in deep recession, with unemployment of 10% interest rates of 10%, and the Pound was struggling to maintain its value against the D-Mark. As soon as markets opened, financial investors piled in to sell pounds to a beleaguered government, and Sterling fell, reaching the floor of the Exchange Rate Mechanism. But, the Conservative government were deeply committed to the ERM as the foundation of its economic policy. John Major and Norman Lamont ordered the Bank of England to sell $24 billion worth of foreign currency reserves in a bid to prop up Sterling. But, it was to no avail. A relatively unknown hedge fund manager George Soros had spent months shorting the Pound ready for what he predicted would be the Pounds inevitable demise.

In a day of frantic trading, the government couldn’t keep up with the volume of selling. The Bank of England had to accept whatever price sellers demanded. In desperation, the chancellor raised interest rates to 12%, which in theory should strengthen the Pound. But, with the housing market already crashing and the economy in deep recession, markets almost laughed off the desperate measure. Normal Lamont told John Major the game was up. But, Major didn’t want to admit defeat for his central economic policy. Not knowing what else to do, they promised interest rates would rise to 15%. It was an act of desperation and the markets knew it. Nothing could stop the selling of sterling. Eventually by the end of the day, the government succumbed to the inevitable, they left the ERM, devalued the Pound and interest rates could fall.

The day changed the direction of the UK economy. The ERM was the precursor to a single European currency, the UK’s disastrous experience left a profound scepticism about the Euro. Without the ERM debacle, Tony Blair would probably have taken the UK into the Euro in 1999. The ERM crisis and sight of flailing ministers caused a huge shock to the reputation for the Conservative management of the economy. Despite having just won an election, support for the Conservatives plummeted from 42% to 29% overnight and it never recovered. The rest of the parliament would be dominated by scandal, sleeze, a diminishing majority, rebellions by increasingly Eurosceptic backbenchers and a general sense in the country that 18 years of Conservative government was too much.

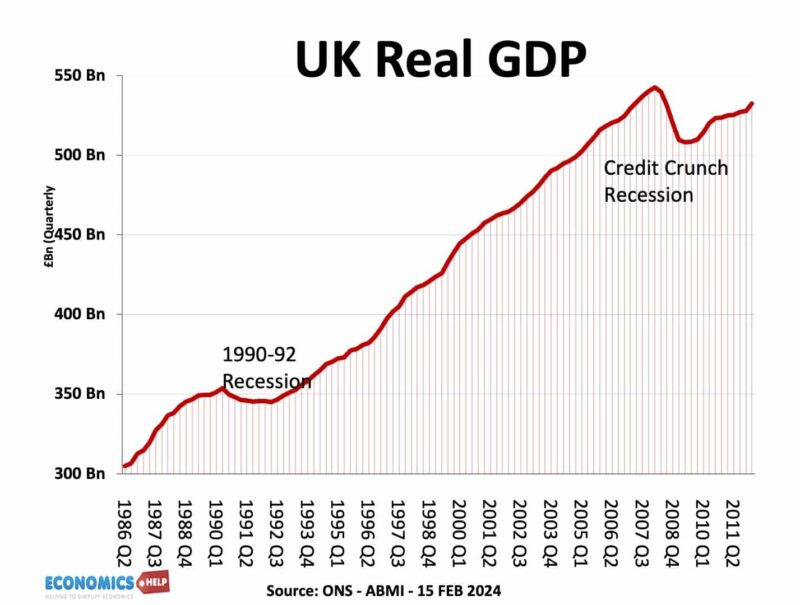

The biggest irony was that leaving the ERM was probably the best thing that could have happened to the UK economy. Many dubbed the ERM the eternal recession mechanism and in the case of the UK, there was a good deal of truth. After leaving, interest rates could be cut, reducing pressure on beleaguered homeowners, boosting economic growth, and the interesting thing is that devaluation didn’t cause any of the inflation that was generally feared. In fact, from 1992 to 2007, the UK went on the longest period of unbroken economic expansion in record. The boom and bust period seemed to be over. In 1997, New Labour won a landslide and they inherited a relatively good economy. National debt just 45% of GDP, low inflation, strong economic growth, the Pound even recovering lost ground.

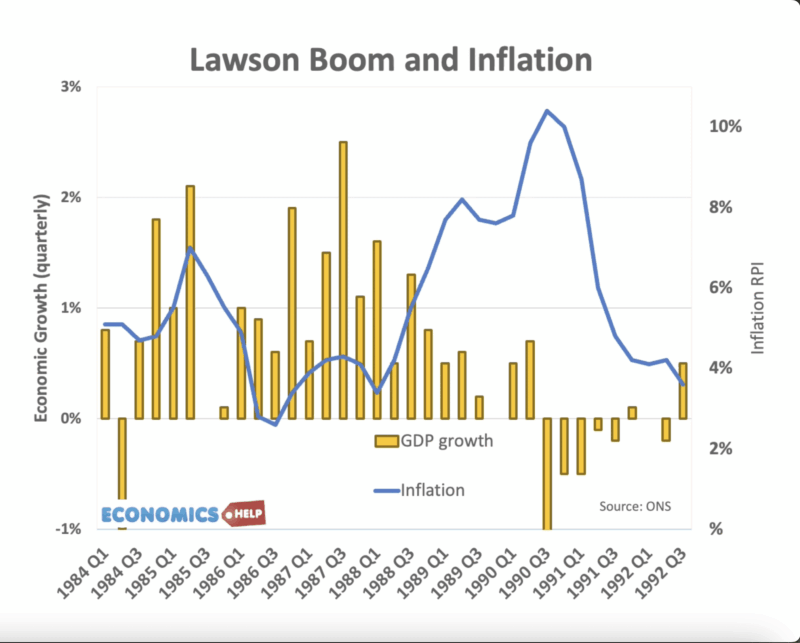

So if leaving was the best thing that ever happened, why did the UK ever join? In the early 1980s, the UK had rampant inflation, a hangover of surging oil prices, rising wages and high growth in money supply. Thatcher’s medicine was high interest rates and monetarism. Inflation fell, but at the cost of a deep recession and a surge in unemployment. In 1983, Nigel Lawson became chancellor and by then the economy was picking up. In fact, over the next six years, the UK economy started to boom, lower tax rates, lower interest rates and deregulation all helped creating rising incomes, and a surge in house prices, especially in the south.

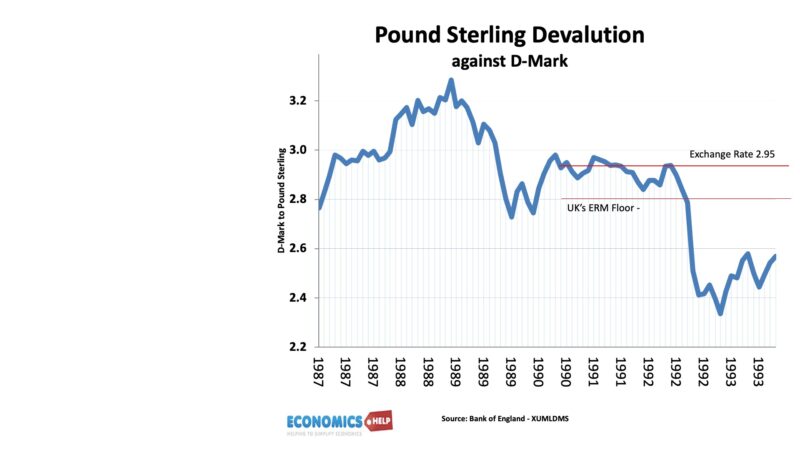

The UK economy grew so quickly, inflation made its inevitable return. The supposed supply side miracle was more hubris than reality Yet to Lawson, there was a simple solution: join the European Exchange Rate mechanism and fix your currency to the D-Mark. In the 1980s, the German economy was the envy of Europe, low inflation and high growth. The idea was that by fixing the value of the pound to the D-Mark, there would be a discipline to keep inflation low and this would help reduce inflation expectations. But Mrs Thatcher was sceptical and refused to join. In fact there was good reason to be sceptical in 1967, there were 11 DM to one Pound by 1989, this had fallen to just 3. The pound was in long-term decline it wishful thinking this could be suddenly be turned around.

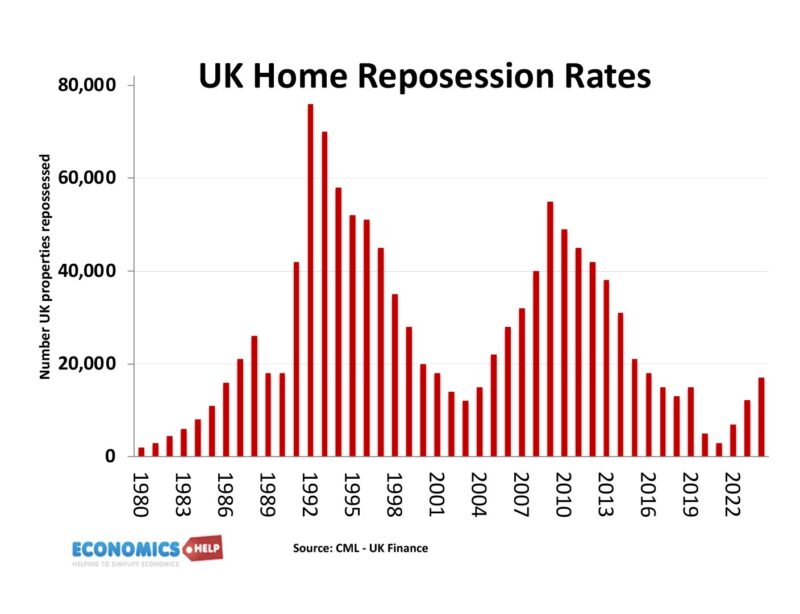

In an uneasy compromise, Lawson tried an unofficial shadowing of the D-Mark, to keep the pound at his desired level. But this required interest rates to increase to a really high level of 15%. But, given the surge in mortgage lending of the 1980s, this came as a huge shock to the economy. Mortgage rates immediately rose and people couldn’t keep up with repayments, reposessions would soar in the early 1990s, to unprecedented levels.

After criticism from within government, Lawson resigned and was replaced by John Major, who convinced Mrs Thatcher to join the ERM at a rate of 2.95. However, to some shrewd investors, this seemed like a bad decision. High interest rates were killing the UK economy, GDP was starting to fall, unemployment was rising and house prices were crashing. In fact house prices fell 20% in the early 1990s, and took nearly 6 years before they started to rise again.

George Soros had steadily built up considerable wealth as a private investor, and he reckoned this exchange rate was not sustainable. UK inflation was three times as high as Germany’s, UK exports were uncompetitive and the high interest rates were depressing the economy. He used his hedge Fund Quantum Fund to borrow in Pounds from banks and buy foreign currency. He also used options and future contracts to short the pound and leverage his position. Basically, he was making a huge bet the UK would have to devalue the Pound or leave the ERM. He would eventually make £1 billion profit on shorting the Pound, using funds he didn’t even own. No wonder he became something of a bogey man.

By September 1992, the UK economy had gone deeper into recession, unemployment was back up to 3 million and house prices were still falling. It was an untenable situation. Yet, the government as a point of pride were committed to the ERM as a cornerstone of their economic policy. To u-turn, would look weak or whatever. But, also the once mighty German economy was also having its difficulties. Re-unification was costly, German interest rates were rising, causing the D-mark to appreciate, putting more pressure on Sterling and other currencies like the Lira. On 15 September, the president of the Bundesbank mentioned to a journalist that a more comprehensive realignment of currencies was inevitable. That was the trigger for markets to go into overdrive and as soon as markets opened the next morning, the selling overwhelmed the Pound.

Jim Trott a former official at the Bank of England said that Black Wednesday was stunningly expensive for the government. During the day, he bought more sterling than at any time in history, but every purchase failed to stem the decline, and each purchase of sterling lost money, when the dust settled the UK treasury estimated Black Wednesday cost an estimated £3.5 billion, though at the time, losses were put at tens of billions.

There was a hope in the Bank of England that the German Bundesbank would intervene and help the UK by selling German D-Marks and buying Pounds. However, Trott remembers: “The cavalry were the Bundesbank. We kept on looking over the hill, but there was no dust and there were no hats and no sabres. And then later when we tried to talk. they suddenly didn’t speak English, which was extraordinary…”

So much for European unity, the ERM certainly gave a boost to the more eurosceptic wing of the conservative party which until 1992, was something of a fringe movement in the Conservative Party. The weakness of the John major and his association with the failure of the ERM, only strenghtened Eurosceptics who would vote against the government in the Maastricht rebellion of 1993.

It also led indirectly to a new inflation policy. Rather than targeting indirectly money supply like early 1980s or the exchange rate, now the UK would target inflation directly. In 1997, New Labour would actually give the Bank of England independence in setting monetary policy and interest rates, a tacit admission, politicians weren’t very good at managing the UK economy. There has never been any interest in managing the exchange rate since.

George Soros admitted that no one other than himself had benefitted from his financial speculation. He actually advocated a single currency, but whilst Tony Blair was definitely willing to join, Gordon Brown, who was shadow chancellor during black Wednesday, became vehemently opposed to Euro and persuaded Blair to not join.

By the was,y if the UK had joined the Euro in 1992, Brexit would have been completely different. It’s easy to join the Euro, but very difficult to leave.

The early 1990s was actually a traumatic period for the UK economy; membership of the ERM distorted the economy, interest rates were too high, and it caused a recession deeper than necessary. The UK economy did much worse than comparable countries. It was yet another self-inflicted wound. But, interestingly, the rest of the 1990s, were relatively good, at least by recent standards.