The 1980s was a decade of divides. The proud industrial heartlands of the north suffering irreversible decline. The City of London enjoying an unprecedented boom. In the early 80s, Unemployment soared to the highest level since the Great Depression, manufacturing fell off a cliff. But not everyone suffered in the 80s. Financial liberalisation and tax cuts saw a boom in finance. Capital flowed into the square mile, leading to soaring profits and rising wages, for some. A country which was once the workshop of the world, now the epicentre of global finance.

But it wasn’t just the new sky-scrapers that were transforming the capital city there was a new ethos of rugged individualism, greed is good, there is no such thing as society. The young upwardly mobile profesionals were living the dream, the first mobile phones, designer clothes, and flashy cars, but most of all Loads of Money. The Yuppie became a pejorative term, the early footsoldiers of gentrification and elitism. It was a stark contrast to the vanishing reality of old working class respectability, honesty and thrift. In fact, the 1980s saw a seeming breakdown in the old British values. Football hooliganism marred the terraces, English clubs banned from Europe. Crime rates soared to an all-time peak. In 1981, a wave of riots broke out in the inner cities, disaffected black youth especially suffering high rates of unemployment and harassment from the police. A breakdown in relations which would take years to heal.

1970s Hangover

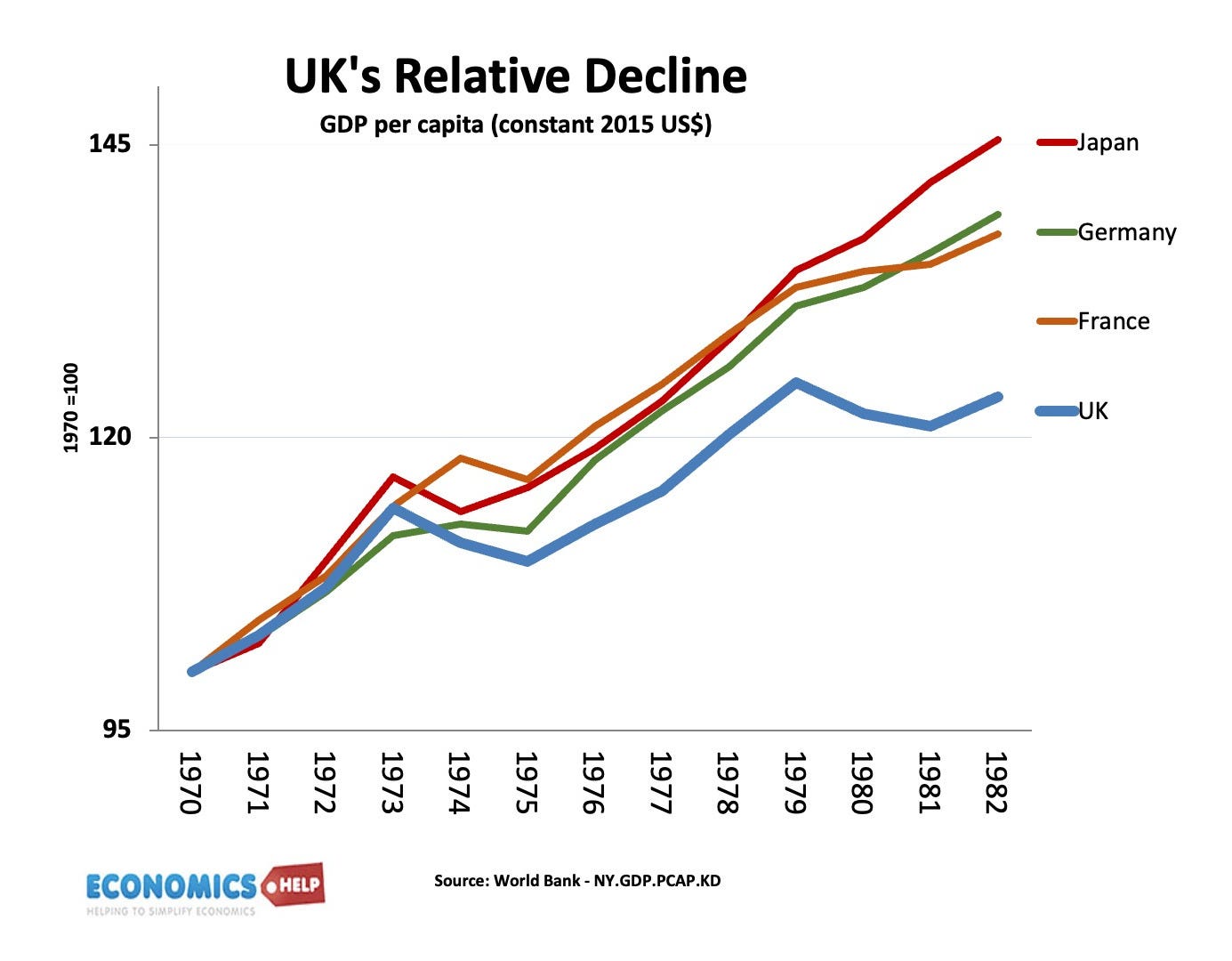

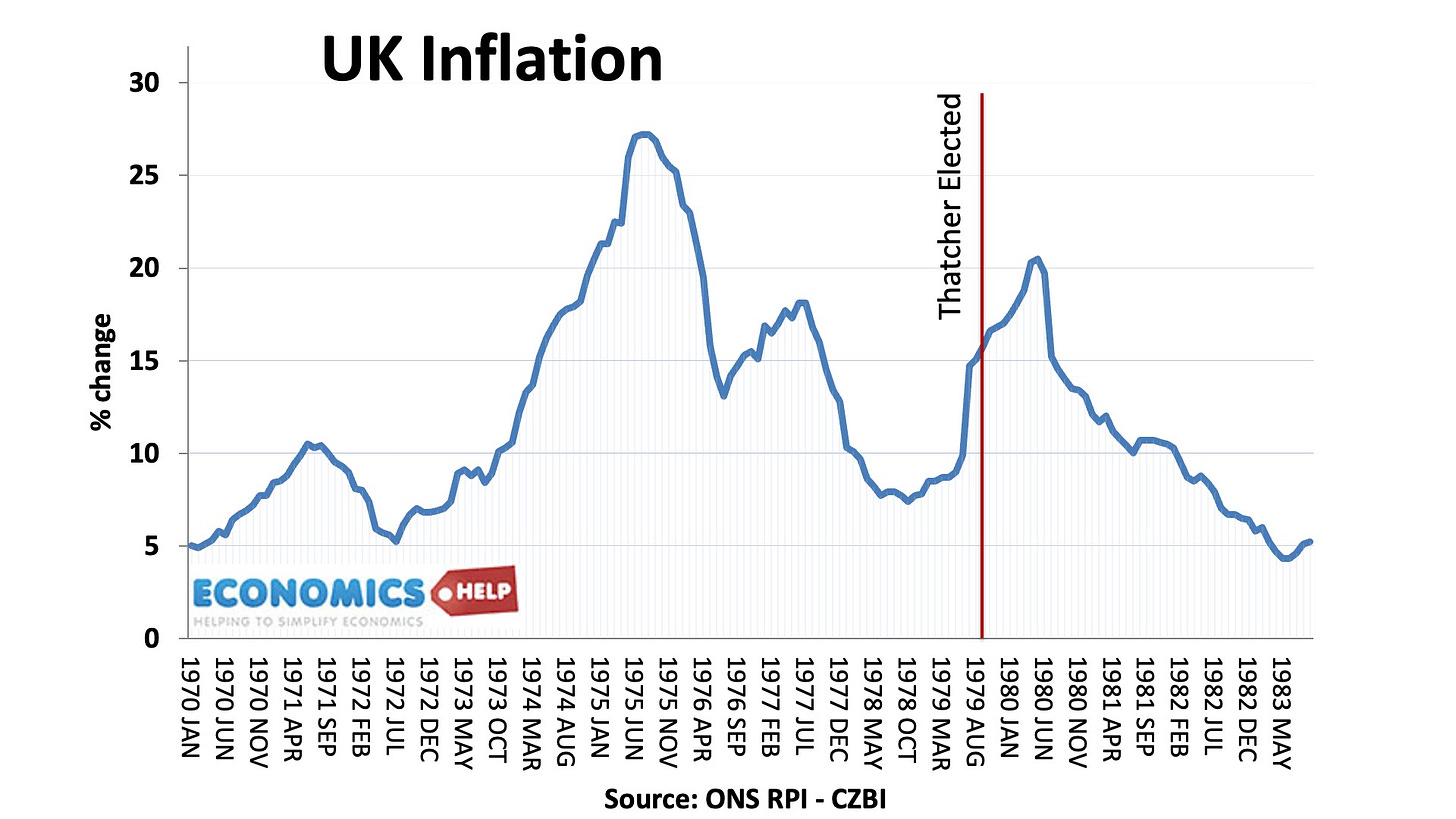

The decade had started with a hangover from the 1970s, rampant inflation, declining productivity, and a nation seemingly forever on strike.

This had to change said the Iron Lady. And If there was one figure who defined the divisive 80s, it was Margaret Thatcher, This lady is not for turning. “No, No, No.” at least you knew where you stood. Ironically, she had come to power in 1979, quoting St Francis of Assisi. “Where there is discord, may we bring harmony.” But, Thatcher was no saint, more revolutionary. Inflation had to be tamed, interest rates were increased, spending cut. The economy went into deep recession 365 economists urged her to change policy, but the lady was not for turning. It was all a far cry from the woolly consensual politics of the post-war period. Out was Keynes and full employment, in was Milton Friedman and free market orthodoxy. She divided opinion like no others, to some a saviour from Britain’s decline and capture by the unions, to others a prophet of materialism, selfishness and a growing economic divide.

Miners Strike

In 1973, she had served as a minister when a Conservative government apparently capitulated to striking miners, 10 years later and Thatcher was ready to take on the miners, and she was ready to do whatever it took. For a divisive decade, Arthur Scargill and Mrs Thatcher were the perfect double act. Both convinced history was on their side, stubborn and unwilling to bend. The miners strike gained widespread sympathy, working men fighting for their jobs, their community and a sense of belonging. Ideals which were perhaps slipping away from the country. But even the miners themselves were not united. Arthur Scargill had pressed ahead without ever calling a ballot. In Nottinghamshire, miners remained sceptical of Scargill’s authoritarianism and they kept working. The struggle became intensely bitter – communities divided, the police versus workers, the state versus the NUM, mining communities themselves driven apart. The Battle of Orgreave caused irreparable damage to the image of a neutral police force, not helped by the later Hillsborough disaster and long cover-up.

Media

Although the public was somewhat divided very largely the print media was on the side of Thatcher. Rupert Murdoch had bought the Sun in 1969, but his influence really doubled in 1981 when he bought the Times. Murdoch fought his own battle with unions. In 1986, he secretly moved the high tech Wapping plant, sidestepping the troublesome print unions. It was another nail in the coffin for union power in the UK. After the miners went back to work, exhausted and impoverished in March 1985, the days of union political influence were effectively over. The Murdoch era brought a new style of media, a media that had no qualms about openly campaigning and pushing an agenda. It was the Sun wot won in, gloated the Murdoch press in 1992, and it was not without considerable truth.

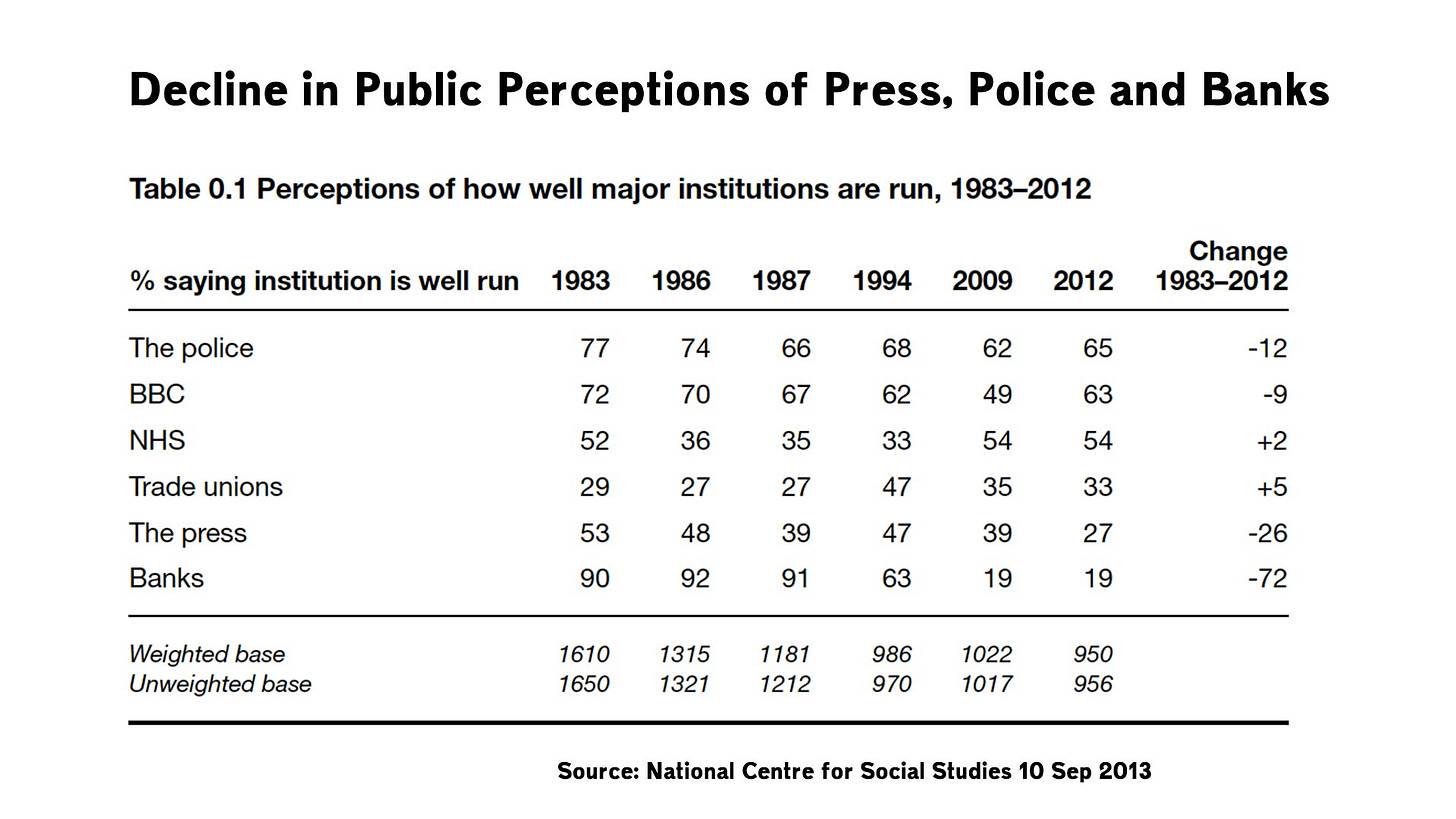

But, one of the striking features of the 80s, was the massive decline in trust in the media. In 1983, 53% said the media did a good job. 30 years later that had fallen to 27%. But, the fall from grace, was not as acute as in banking. Amazingly 90% felt the banks did a good job in 1983. 30 years later that would be just 19%.

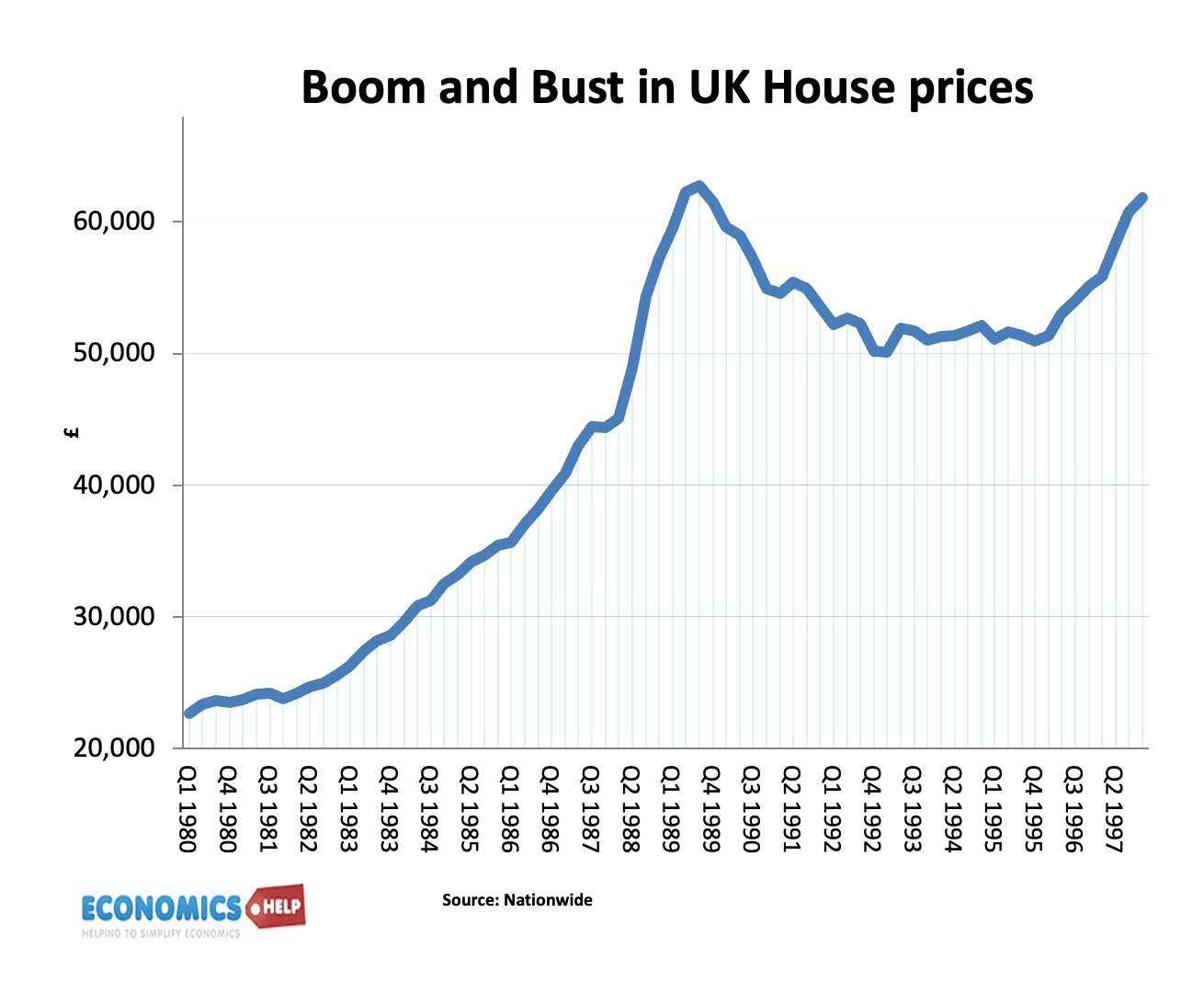

In the early 1980s, building societies lent mortgages based on existing savings. But, that was too boring and too unprofitable for the brave new world of the 1980s. The Big Bang financial regulation overturned decades of regulation and replaced with a profit-seeking culture, where bankers were rewarded for taking risks, but when things went bust, it would be the taxpayer who would bail them out. As banks were deregulated, mortgage lending increased.

It began the great UK house price boom, which would cause prices to soar over the next three decades. Home ownership rates increased, largely because of the right to buy. Council homes could be bought at a discount by tenants. But, like many aspects of the 1980s, it stored up problems for the future. There was no building of new council housing to replace those sold. It would lead to a system of winners and losers in the housing market. If you had bought a house in 1981, today it would have increased over 1,000%. But, equally, if you’re priced out and have to rent, the share of income going on rent, has increased from 10% in 1980 to 30% in 2025.

Privatisation

It wasn’t just council housing that was privatised in the 1980s, it was pretty much everything the government could get its hands on. British Airways, water, gas, electricity, and telecoms. Selling off the family silver bemoaned former Conservative PM Harold Macmillion in 1985. But for those buying shares at knock-down prices, privatisation was an easy way to make easy gains. There were some benefits of privatisation in those industries with competition. But, handing over ownership of water to private companies would see decades of underinvestment as new private firms took on debt, and paid themselves generous dividends. And what of the North Sea Oil bonanza? Which did so much to help government finances. Norway invested in a sovereign wealth fund, now worth over $1 trillion. The UK offered tax cuts to the wealth. Tax cuts, privatisation, unemployment and financialisation of the economy, all lead to an inevitable growth in inequality. To cap it all, Mrs Thatcher had the bright idea of a poll tax. The unemployed should pay the same amount of tax as a millionaire. The 1980s dream in a nutshell.

Cold War

At the start of the 1980s, the UK and US were in the midst of a red-hot cold war. In 1983, Reagan called the Soviet Union the evil empire, and Thatcher was the devoted follower of Reagan’s rhetoric and ideology. Both saw the world in stark terms, capitalism vs communism, good versus evil. In 1981, US nuclear cruise missiles were brought to the UK, just at a time when fear of nuclear war was reaching fever pitch. In 1980, the UK government produced a booklet, “Protect and survive” about what to do in the event of a nuclear attack. It helpfully informed you that if you lived in a bungalow,w you would have no protection against a nuclear bomb, but if you had one, you could fill your cellar with bottled water and toilet paper, it might keep you alive a few days. Needless to say, anxiety about a nuclear attack skyrocketed. But, some women wanted a different approach. Over 30,000 women descended on Greenham Common to protest the arrival of American cruise missiles. CND enjoyed a surge of support and was even embraced by Michael Foot, the leader of the Labour Party in 1983. In an age of divisive politics, Labour swung to the left and offered a radical manifesto of unilateral nuclear disarmament, massive renationalisation and wealth redistribution. It was later referred to as longest suicide note in history. At least you couldn’t argue the politicians were all the same. In 1983 Labour slumped to 27% of the vote, only the vagaries of the first past the post system meant they hung on to parliamentary seats. The Conservatives also helped by the Falklands War Effect. The new centre party the SDP had briefly enjoyed a poll lead, but the 1980s were not the time for a moderate centre party and they folded within a few years.

But, for all the talk of the 1980s as a divisive period in UK politics, the wider world, saw an unexpected breakthrough, almost miraculously, the Soviets elected a new leader, Mikhail Gorbachev who promised reform, democracy and freedom. Even the hard-bitten capitalists Reagan and Thatcher were smitten with a man who they felt they could do business with. Gorbachev didn’t just make speeches, he followed it through. With a wave of change sweeping Europe, people spontaneously demanded freedom and the end of the Iron Curtain. Any other soviet leader would have sent in the tanks, but Gorbachev said yes to self-determination. The Berlin Wall fell, and the iconic division of East and West dissolved almost overnight. It was a moment of optimism, unification and a real sense that history was changing.

Events that united a nation

Back in Britain there were other memorable events that united the nation. The 1981 wedding of Charles and Diana was probably the high point of the royal family in Britain. 28 million turned into watch the fairy tale wedding live on tv. It was an event that transcended class, politics and the economic malaise of the country. The fact the fairy tale wedding was more of a doomed threesome would not really emerge until the next decade, we could enjoy the spectacle for a while. Other memorable events of the 1980s included Band Aid in 1985, a grassroots response to the sight of starvation in Ethiopia and the global divide in wealth.

Apart from the threat of nuclear war, the other great fear of the 1980s, was AIDS. If you didn’t live through the time, it is hard to understand the strength of feeling or perhaps fear. In fact, the experience would lead to a softening in attitudes to homosexuality. The irony of Thatcher’s hold on British politics, is that in some respects, Britain became more liberal, the old victorian attitudes to sex, falling away for good.

Personal note

But born in 1976, my abiding memory of the 1980s, was not economics, global events or culture, but the 1986 World Cup quarter final against Argentina. The nation sat glued as Maradona dashed the hopes of a nation – first with blatant cheating and then the most beautiful mesmeric goal ever to grace a world cup. At that age, it was too much to lose. But at least, I knew England would probably be winning a major trophy very soon…

Sources

https://natcen.ac.uk/publications/british-social-attitudes-30

https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document%2F106689

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-45559456

https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/SN06623/