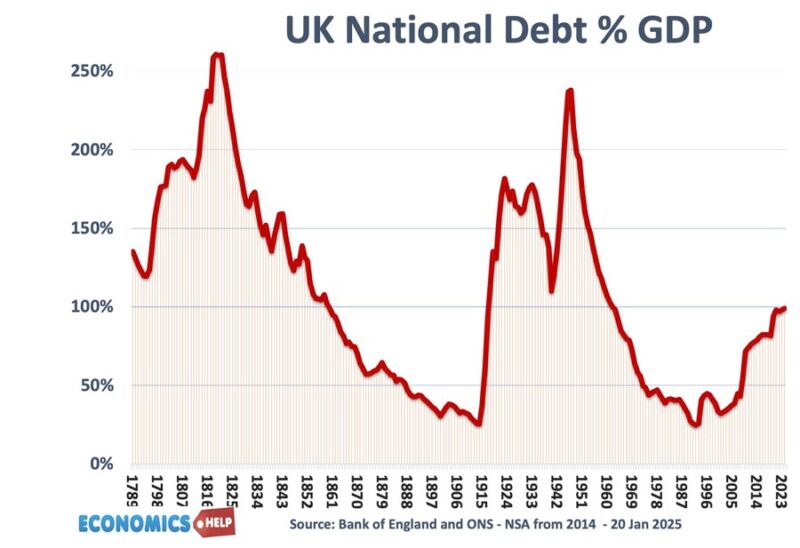

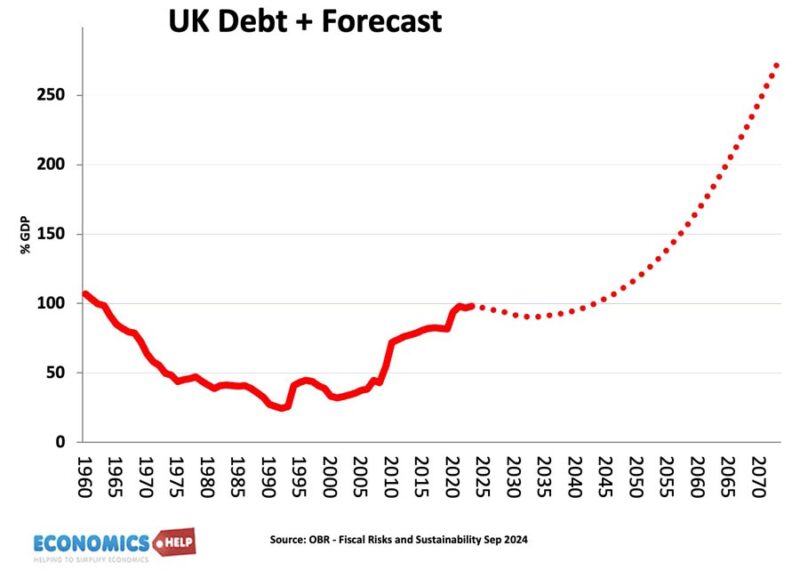

This is UK National debt since 1780. It tells part of the national story. Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo didn’t just change European history, it saved Britain from bankruptcy. The two world wars once again saw debt surge as the debt provided an emergency lifeline.

However, despite no global war, debt is once again rising and is forecast to keep rising over the next decades. And it’s not just the UK, you can see a similar trajectory in the United States. Who is buying all the debt? Will the UK go bust? And who benefits from this debt?

Who Buys Debt?

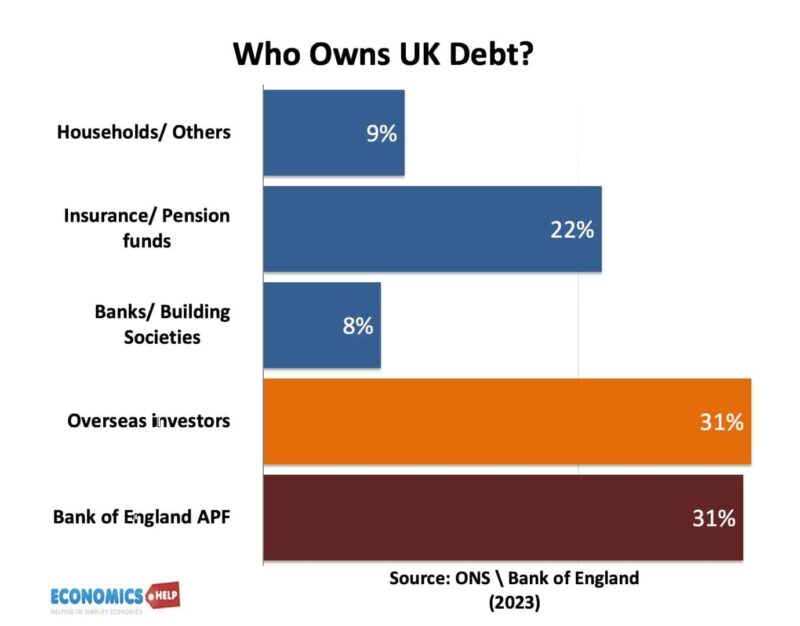

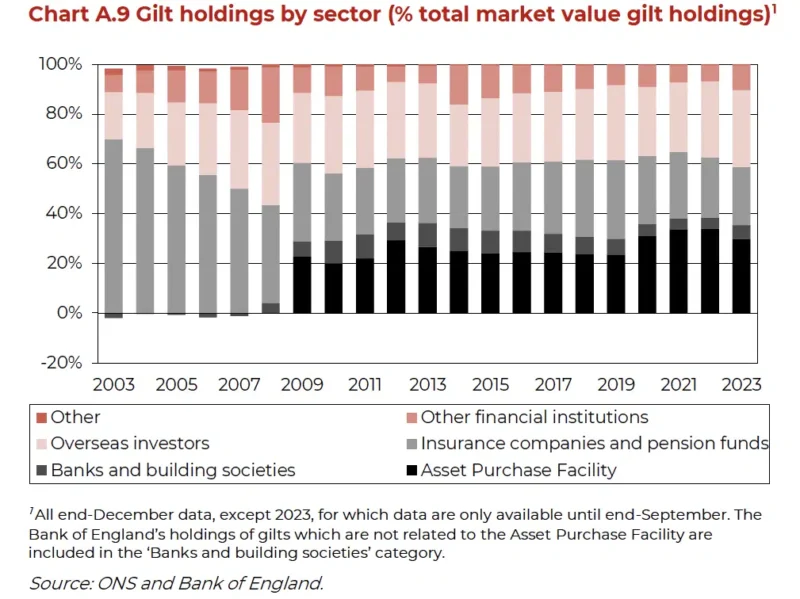

When governments spend more than they receive in tax revenue, they make up the shortfall by selling government bonds. These are typically bought by private investors, pension funds, investment banks and wealthy individuals. If you have a pension, you will indirectly have a stake in a few government bonds. But, mostly, it will be the richer investors, with significant spare savings. In the UK and US, around 30% of gilts are held by overseas investors. In recent years, government bonds have also been bought by Central Banks through quantitative easing. More on this later, but this shows who owns the UK’s government bonds at the end of 2023.

Also, it is interesting to see how this has evolved in the past 20 years. In 2003, insurance and pension funds owned nearly 70% of all UK bonds. Overseas investors are 18%, and the Bank of England nothing. We have become more reliant on the Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility and overseas investors. But, interestingly, the Bank of England is now reversing quantitative easing. It is selling those bonds it bought back onto the gilt market. So the government not only has to sell the bonds to fund current borrowing, but also the Bank is selling additional bonds. With gilts maturing, the debt management office will be selling £296bn of government gilts in the financial year 2024/25.

What if people stop buying?

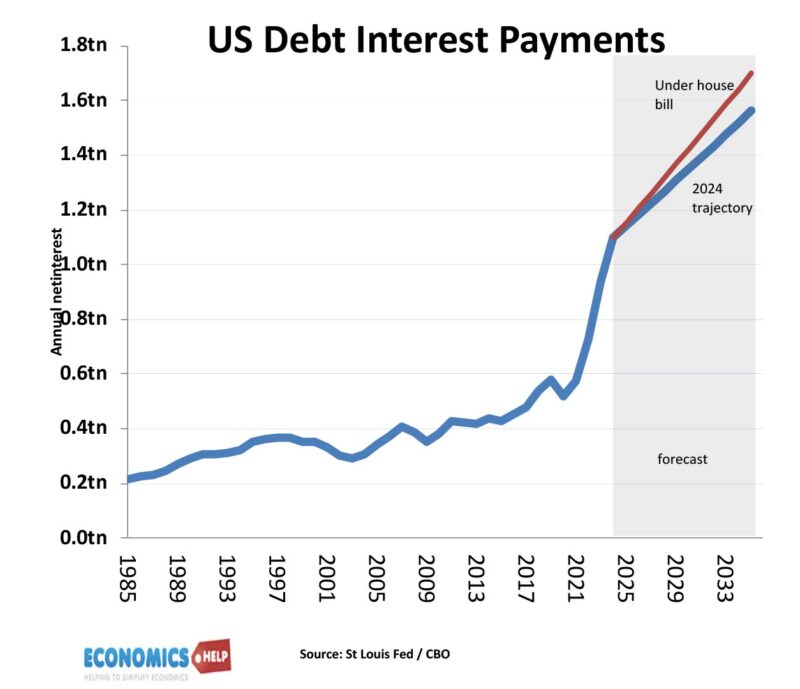

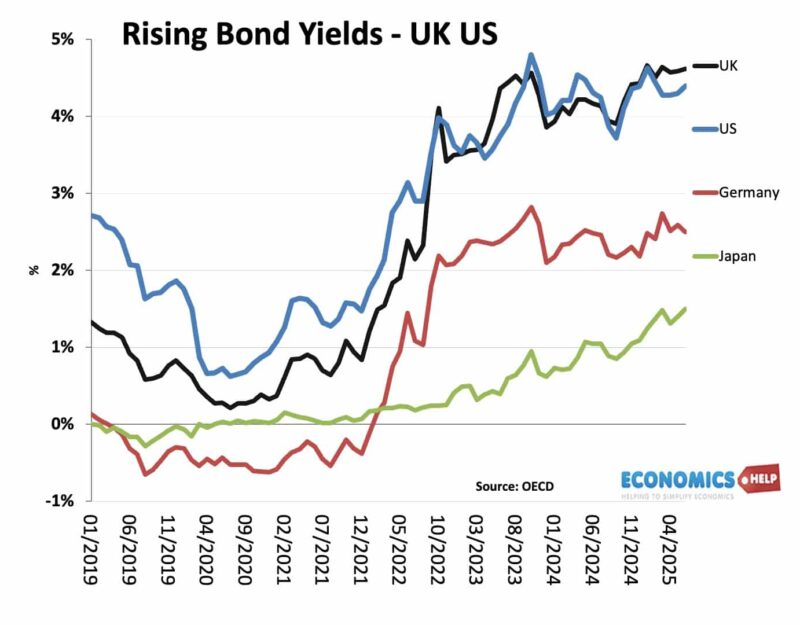

This sounds like a lot of gilt sales, and a good question to ask is what happens if the private sector and foreign investors don’t want to keep buying UK gilts anymore? Well, firstly, the government have to offer a sufficiently high interest rate to attract the private sector to buy. If government bond yields are higher, it will encourage investors to buy bonds rather than say invest in stock market. When inflation and inerest rates go up, this causes higher bond yields to keep investors buying UK bonds. In recent years the cost of debt interest has increased quite substantially. UK debt interest payments have doubled since 2021 due to the higher inflation and rise in interest rates. It means that debt interest payments are now one of biggest components of UK government spending. And this is one big cost of debt – it is £120bn that can’t be spent on health care or lower taxes. It is a similar story in the United States, where growing budget deficits are increasing the debt interest cost. The US debt interest bill could reach $1.8 trillion in 10 years time.

Global Savings

It is worth pointing out that the private sector does have a lot of savings. UK households have a total of £2 trillion in cash savings, Uk pension funds have assets of £3 trillion. There’s an estimated £21 to £32 trillion in offshore bank accounts. In 2024, the global asset management industry will have $128 trillion of funds to invest. The point is that there is a lot of global savings, which can be used to buy bonds, if investors think it is the best option. Amongst the Super rich, there is a lot of tax avoidance; they tend to have lower tax rates, which means there is a lot of money to buy bonds.

Who Benefits from Debt?

In a national emergency, government borrowing provides an emergency stop gap of funding. In Covid, the budget deficit reached 15% of GDP, but this helped provide support during lockdown and keep the economy going. Another good time to borrow is in a recession. In a recession, spending falls, people save more and interest rates go down. If the government tried to balance the budget, they would need higher taxes and spending cuts. But that would make the recession deeper. In fact, the government should borrow more, increase investment and stimulate economic growth because once the economy is growing, it becomes easier to pay back the debt. The big reduction in debt in the post-war period was not due to continual austerity, but from a long period of economic growth. In fact, the reduction in debt occurred despite setting up the welfare state and the NHS.

Debt interest Payments

However, if the economy is growing and interest rates are relatively high, increasing borrowing has several drawbacks. For example, the United States is proposing to cut taxes mostly for the rich and borrow more. Richer households benefit from tax cuts, which will give them more savings and so they can buy US bonds. The government then pays an interest on the bond. You could say the net effect is similar in that those richer households are funding government spending by buying bonds rather than paying taxes. But if you levied taxes, the government would save the debt interest payments. It is worth pointing out that Keynes advocated borrowing in the great depression, but he also advocated reducing the budget deficit during growth. The problem is when the economy stagnates like the UK in recent years, it becomes very hard to reduce the budget deficit.

What causes default?

If you look at countries that have defaulted on their debt, usually there is some serious structural failing with the economy. Venezuela defaulted on debt in 2017 after a fall in oil prices caused GDP to collapse and currency to fall. There was also corruption and the printing of money. Argentina have defaulted, usually after printing money and high rates of inflation caused a fall in the currency, making it impossible to repay debt denominated in the dollar.

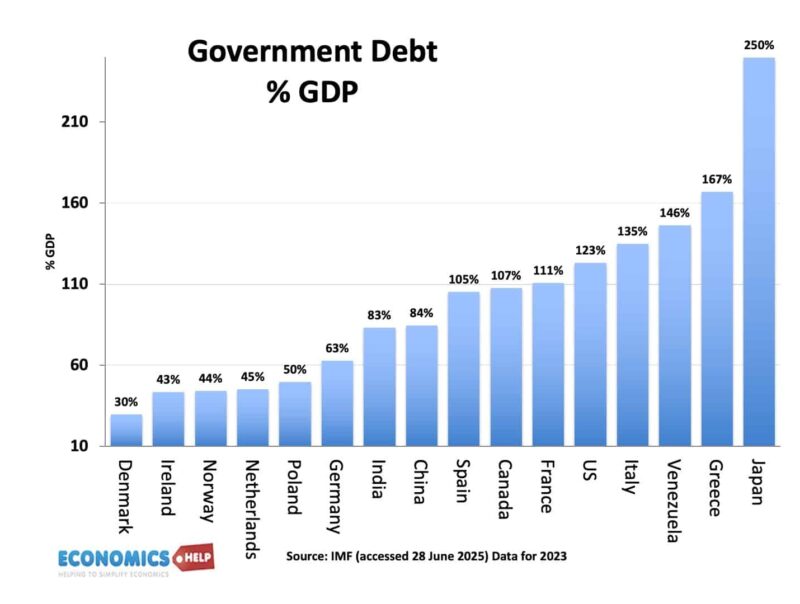

If we look at different levels of government debt, there is a big variance between Denmark at 30% and Japan at 250%. Japanese debt is a little misleading. Its gross debt is really high, but government bodies also have large financial assets, such as holding $1 trillion of US debt. So Japanese net debt is closer to 150% of GDP. Still high, but also Japan funds most of its debt by selling to domestic savers. If a country has its own currency and sells the majority of debt to domestic savings, you can say the country will never default because it can always create money to buy its own debt. This is true to one extent, but if you create too much money, it will cause inflation. Inflation will cause a partial default because inflation reduces the real value of bonds. This happened to some extent in the 1970s, when inflation was much higher than expected and bondholders lost out.

Bond Yields

For many years, Japan had very low bond yields, despite very high debt. But this year we have seen a rise in long-term bond yields in many countries. This reflects an uptick in inflation, but also a growing concern about the long-term fiscal sustainability of major economies. Bond yields can bring down governments. In September 2022, bond yields rose in response to the Truss mini-budget. When markets lose confidence in government policy, it can force governments to u-turn. Sometimes fear of bond market can be used to justify austerity, even if there is strong demand for buying debt, like in the early 2010s. Bill Clinton’s political advisor said, if there was reincarnation “I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.”

Why is debt increasing?

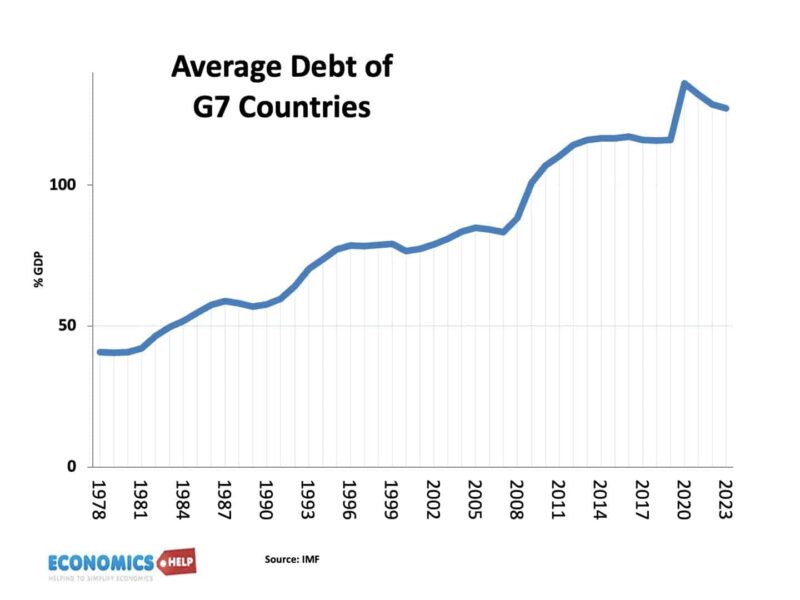

In recent decades, most advanced governments have seen a rise in government debt. The average debt of the G7 has increased from 41% in 1978 to 127% in 2023.

On current policy, debt is forecast to rise in the UK. This reflects a big change in demographic factors. Populations are ageing, which means higher spending on health care and pensions, but with shrinking working age population tax revenues will not keep up. A very few countries invested in sovereign wealth funds, investment protected from day to day spending, but giving interest on investment to help meet spending. Norway, and the oil rich states have built up trillions. But, most western economies like UK and US never created a pension fund, using North Sea oil revenues to cut taxes. So any future pensions will need to be paid out of future tax. There are also many other factors, for example, the UK has a rapid rise in sickness and disability benefits, a rise in social care spending and a desire to spend more on military spending. The problem is that as the current Labour government have found, once the electorate have certain spending or tax breaks, it is very hard politically to take it away. It is easy to add a policy, like say “pension triple lock” guarantee. But, after you’ve introduced, you end up being stuck with it. If you can’t increase taxes or cut spending, borrowing is the easiest short-term political response.

Can’t we Just Print Money?

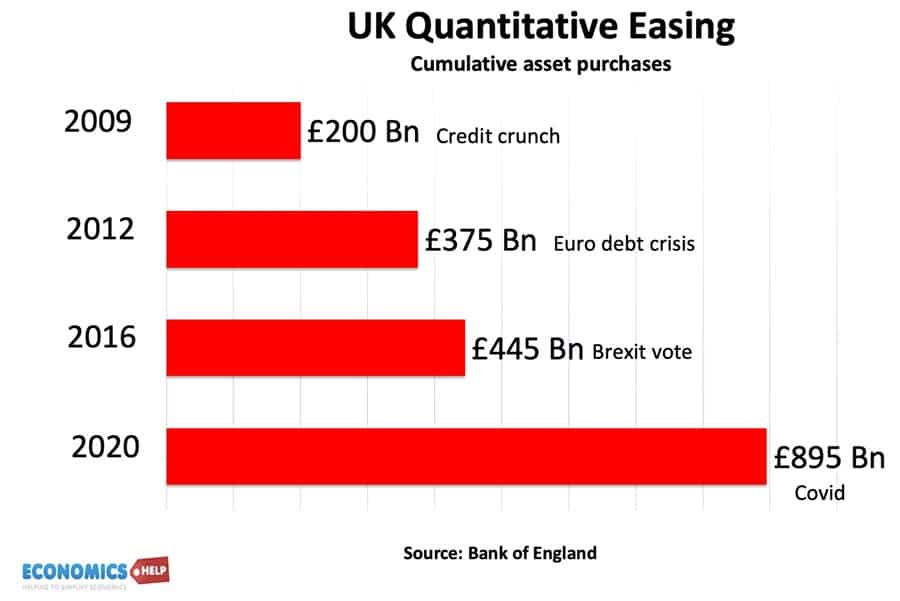

In 2009, Central Banks started to create money to buy government bonds as part of quantitative easing. The main motive was not to finance the government debt. They did it because interest rates were close to zero, and the economy was still depressed. They wanted to create money to try and stimulate economic activity. Funding the debt was kind of a side benefit. However, in 2022, inflation and interest rates rose, so Central Banks started to reverse quantitative easing as they felt the monetary stimulus of QE should be taken away.

MMT

A modern monetarist theory of debt is that governments can spend without collecting taxes or borrowing, but just get the Central Bank to create money. The key constraint is not borrowing but inflation. In the MMT model, the Central Bank would concentrate on creating money, keep interest rates very low, and the government would control inflation through taxes. I remain sceptical about this because I wouldn’t trust the government to control inflation through raising taxes, it’s virtually politically impossible for a start. Also, creating money to buy debt is fine when inflation and interest rates are very low, like the 2010s. But creating money to funnel into the real economy could soon create inflationary pressure. Also, there are few if any, examples of successful MMT theory in practice, possibly Japan and Singapore are floated. But, there are many examples of countries printing money where it has been a disaster, Germany, Zimbabwe, Venezuela.

Is UK Going Bankrupt?

Is UK going to go Bankrupt? Definitely not in the short-run. The UK has had much higher debt levels in the past. Also, it is true with own currency UK can always create money to buy bonds if necessary. However, that doesn’t mean it can’t become an increasing problem. The projections for debt are a concern because they are due to long-term factors, which may coincide with lower growth rates. What will happen is that we could end up spending a much higher share of national income on debt interest payments, which is good for bondholders, but with an opportunity cost for standard tax payers. And it is possible that if growth remains stagnant we will get to a dynamic where debt becomes an ever-increasing problem.