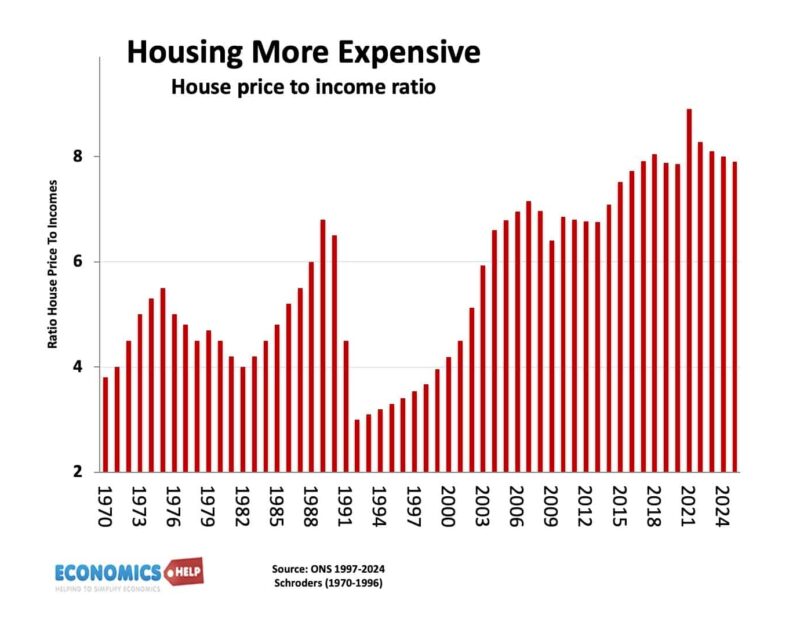

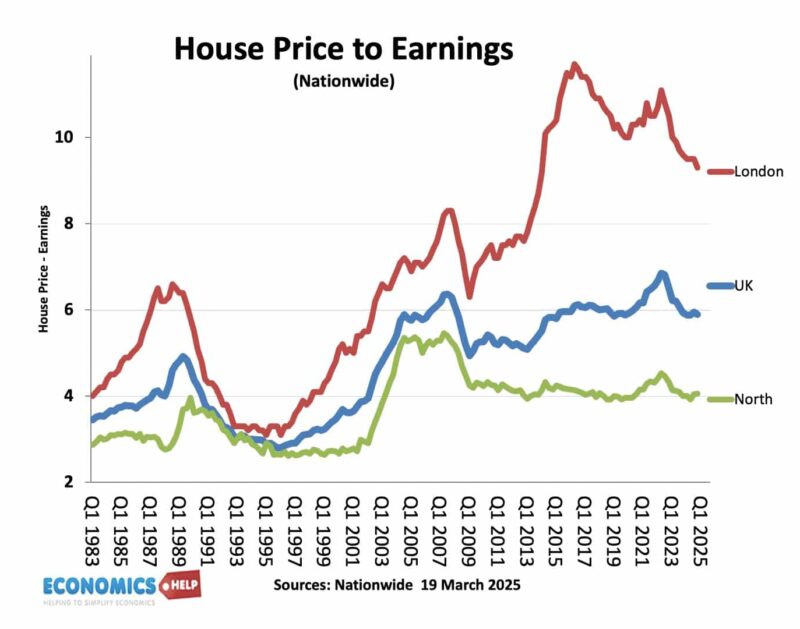

It’s hard to believe but there was a time in recent memory when the average worker could buy an average house for four times their salary. The post-war period was a golden era for home ownership. Home building rates were high and the average worker could buy an average house with a standard mortgage. Home ownership rates soared to a peak in 2008, of 72%, it was the great British dream own your own property. And those who bought, saw wealth increase to unprecedented levels.

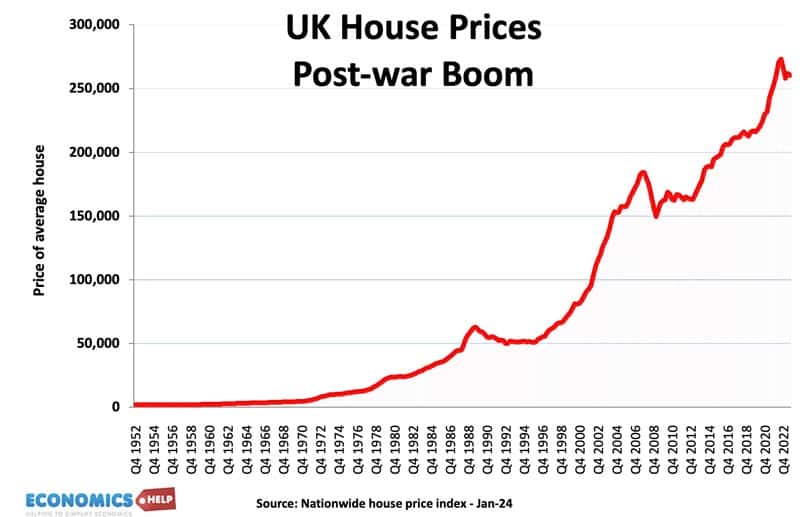

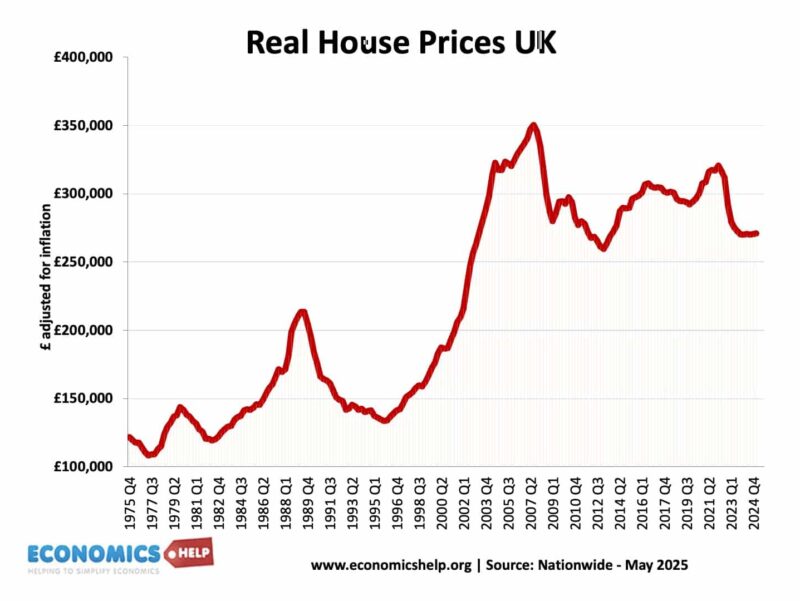

In 1983, average house prices were £27,000. Today, it is £270,000. If you bought a council house at a 50% discount, it was more like a 2,000% gain.

Even if you took inflation and wages into account, housing seemed a one-way bet.

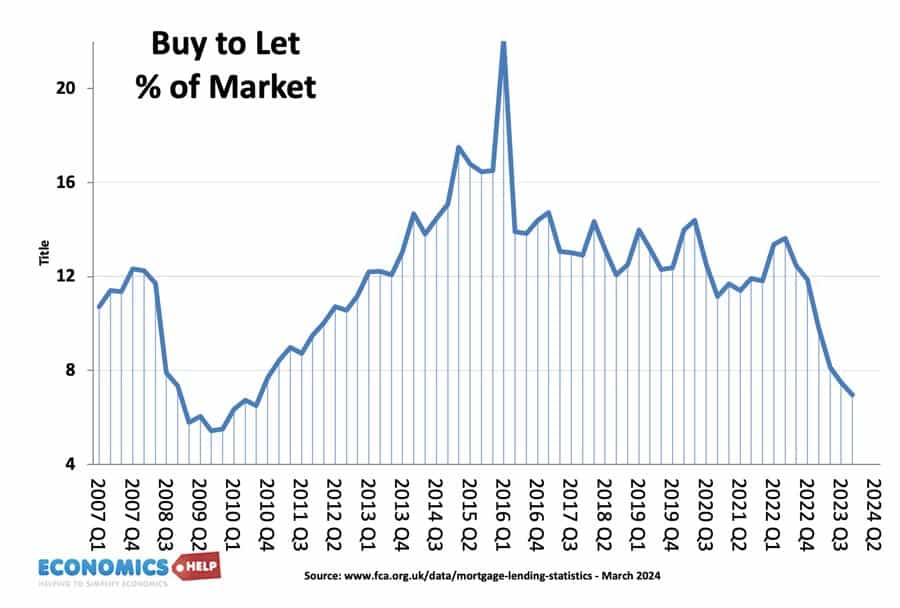

From the mid 1990s to 2008, real house prices doubled and for those whose house was their primary residency, no capital gains. Understandably, the soaring prices combined with relatively low interest rates caused a boom in buy-to-let.

Prices were going up, yields were good, tax breaks were numerous. Buy an old house, install some double glazing, and flip it for a huge profit. And that’s before all the rental income. However, this so-called golden era of housing investment had a darker side. It created a system of winners and losers. The surge in house prices faster than inflation and wages meant that many who had benefited from the housing ladder were metaphorically pulling the ladder up with them.

For a new generation entering the housing market, buying a house was more nightmare than dream. Nine times income, more in the south and London, where the best graduate jobs are.

2008 Turning Point

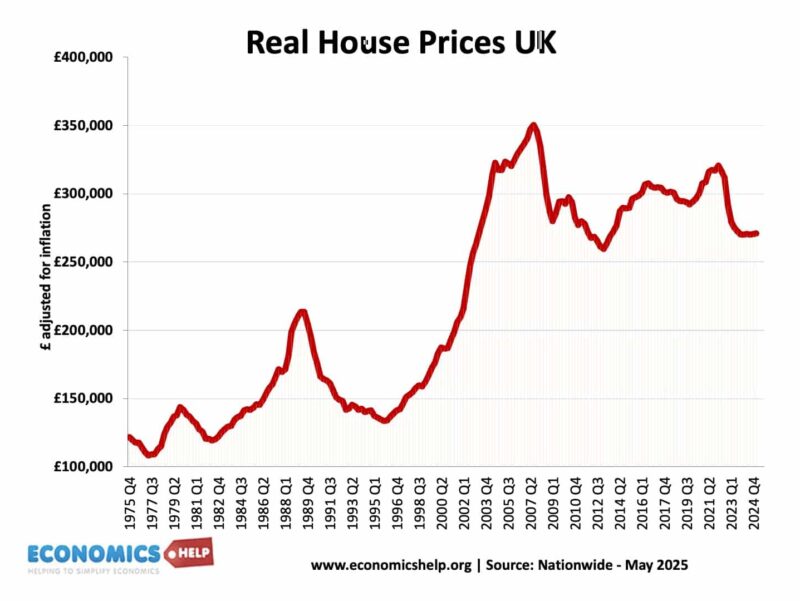

But 2008 was the first of the large turning points. House prices crashed for the first time since the 1991 recession. A 20% fall punctured the irrational exuberance of investors, a reminder that there is no iron law which says house prices have to keep rising, even if you do have a historical shortage. But, the credit crisis and subsequent economic stagnation did more to distort the market; we had 13 years of zero interest rates. And in the aftermath of the housing crisis it was once again buy-to-let investors who snapped up houses with cheap mortgages. House price to earnings rose, home-ownership rates started to fall and an era of stagnant wages, affordability worsened. Home ownership was now linked to parental wealth like never before.

Easier options

Rather than fix housing problems through increasing supply, the government chose the easier options, help to buy for first time buyers – and buy to let investors were hit with higher stamp duty, higher capital gains and phasing out mortgage interest relief. Since 2016, with more regulation and higher tax, the buy to let mortgage segment has slumped. But, it isn’t just about regulation and tax, house prices are no longer the one-way bet of previous decades. And this is one of the big changes.

Adjusted for inflation, house prices have fallen since 2007. Whilst the US stock market has given high returns and gold rises faster than inflation, buying a house is no longer a guarantee of easy capital gains. Whilst there may have been no crash in nominal house prices, the problem is that house price affordability is so stretched, there is little room for a new boom. The reality is that despite lower inflation adjusted house prices, we are still at historical high levels of unaffordability. Prices are out of reach. A whole generation of households mostly, though not exclusively, young are trapped by a housing market that is not working.

The bare truth is that without getting help from wealth, it can seem impossible to buy, unless you move up north to Scotland or Humberside, areas which have seen the biggest price rises in recent years. The egalitarian nature of the housing market is no more, and it is causing economic and social problems.

A prospective buyer currently faces having to save for 18 years to get a big enough deposit compared to just 3 years in 1986. And, for a working-age population experiencing stagnant real wages and rising student debt, there is little hope.

Renting

But, the alternative of renting is equally undesirable. A relative shortage of rental properties compared to the rising population means that rents have risen faster than inflation and have burdened households with record housing costs as a share of income. It’s also hard to save for a housing deposit when so much of your income goes on an expensive rental.

Why it is difficult to solve

Given the continued crisis in housing prices, why has is it proved so difficult to do anything about it, and does it mean the so called golden era is now out of reach? The housing market has fundamentally changed and this is why it is so difficult to put the genie back in the bottle.

Firstly, the post-war period was a period of rising wages. But, since 2008, that post-war growth of 2% has slowed down to slightly above 0%. This is why falling real house prices have done so little to improve affordability. Secondly, in the 1980s, and 90s, there was widespread financial deregulation, which led to a surge in the type and scope of mortgage lending. It led to a big growth in demand, which before had been curtailed. In 2005, I bought a house with an interest only, self-certification mortgage – a mortgage five times income. Happy days. In the late 1960s, household debt as a share of income was under 60%. By 2008, it was 158% of GDP. The rise in wealth was also marked by a rise in household debt.

Who is still buying?

The other good question is that if many households on average wages are priced out of the housing market, who is actually buying the houses to keep prices inflated? Firstly, inherited wealth is increasingly important. The value of estates is steadily rising. Which is hardly surprising, if house prices go up so will the value of estates. Where does this money go? It mostly goes back into the housing market. If you’re renting, and inherit £100,000 – what would you do? Finall,y you can buy. But parents increasingly want to help children before they die, parental gifts to help buy have more than doubled since 2007. But, this is only going to get more dramatic in the coming years. The baby boomer generation will be passing on unprecedented wealth in the next few decades. Where will this wealth end up? You guessed it – a lot will end up in the housing market. The Housing market has become a place to recycle its own wealth. Some call it a ponzi scheme, though actually a Ponzi scheme – is the wrong term. Also, the other factor is that whilst private buy to let investors drop out of the market, we are seeing a rise in institutional buyers Lloyds, Barclays, US private equity like Blackrock are all happy to buy up UK property as a long-term investment. Buying with cash, they are less worried about quick wealth gains, but see it is as stable returns. The sad thing is that as rents rise, the government pays more on housing benefits. In effect, the private equity investors are partially subsidised by the government. If you want a graph to see how the UK housing market has changed in the past 40 years, we used to spend money building houses now we spend money subsidising private renters.

Housebuilding

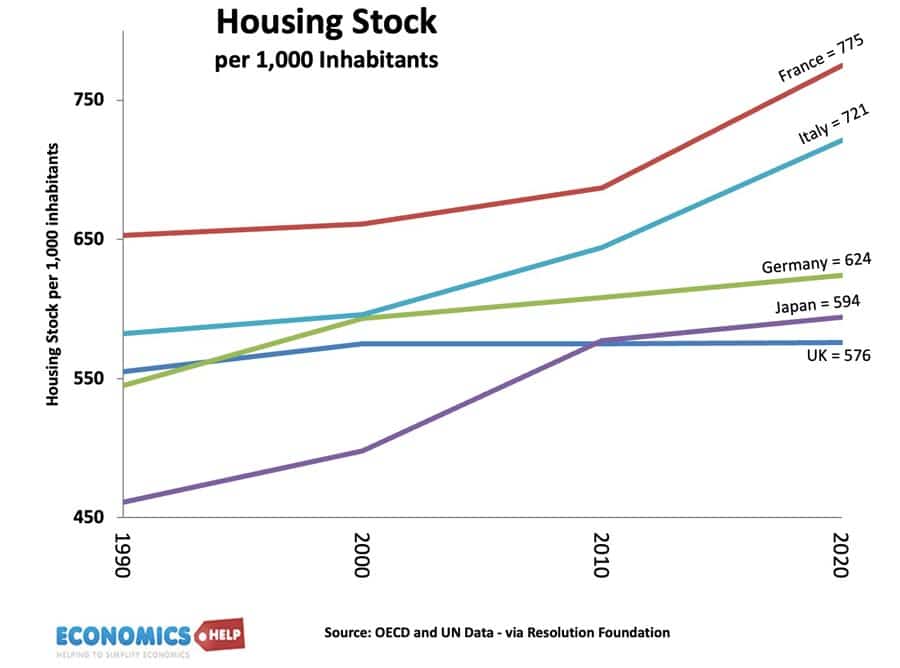

UK homebuilding reached a peak in the early 1970s at 400,000 a year. This included significant amounts of social housing. But, in 1980, Thatcher started to sell off council houses, but there was no reinvestment, the social housing stock fell, and private sector building was limited. Compared to European countries, the UK built fewer houses.

According to some think tanks, there is a shortage of over 4 million houses. It is not surprising, the UK had the largest rise in real prices. On top of low house building, the population has significantly increased, largely driven by high levels of net migration. Reaching a peak in 2023 of nearly 1 million. With house building struggling to get above 200,000 a year, let alone the government’s target of 300,000+, the fundamental shortage is there to keep prices and rents elevated.

Expensive to build

As any commentator will say, just build more houses, but the problem is it is really expensive to build houses. We use the same labour-intensive techniques as the 1930s. This is why the cost of constructing houses has increased faster than inflation. In 1960, a typical 3-bed house may cost £720–£1,080 to construct. Today that is £162,000–£198,000. Since 2000, construction costs have more than doubled. It’s not just labour costs, but also more expensive raw materials, also more regulations, and the risk of planning obstructions.

Government policy

The other aspect of the housing market is that government policy is always torn two ways. There is the awareness that housing is too expensive and this holds back the economy. But, there are also powerful political pressures fundamentally opposed to change. An opinion piece in the Times by Matthew Syed talks about need to address inequality through big changes in tax structure, e.g. land tax, end to private property relief, but these would be bitterly contested. The government make a big effort to build 1.5 million homes, but once in power, they will realise the enduring political strength of NIMByism. The Lib Dems manage to straddle a political tightrope by having a national target of 380,000 new homes a year but win local constituencies by opposing building.

Now, what about the weakness of the UK economy? Doesn’t this make house prices vulnerable to falling?. In recent months, the labour market has weakened and the economy has continued its trend rate of very low growth, even as inflation has remained above target. But, at the same time, if the economy continues to stagnate, it will mean lower interest rates and as interest rates fall, it will only make it more attractive to buy rather than rent. And given the difficulty of builing houses, once again, mortgage lending criteria have been weakened, risking a new rise in mortgage lending.

So this is why housing market has changed, it’s unaffordable, but the political solutions are unpalatable. We are torn between housing insiders and housing outsiders, but this division of wealth will only be a source of rising tension, and it is worth fixing.

Sources

https://www.economist.com/britain/2024/01/11/the-housing-ladder-1950-2005

https://www.ft.com/content/985a608e-17a3-42ff-abb1-d78a10627a12

winner losers