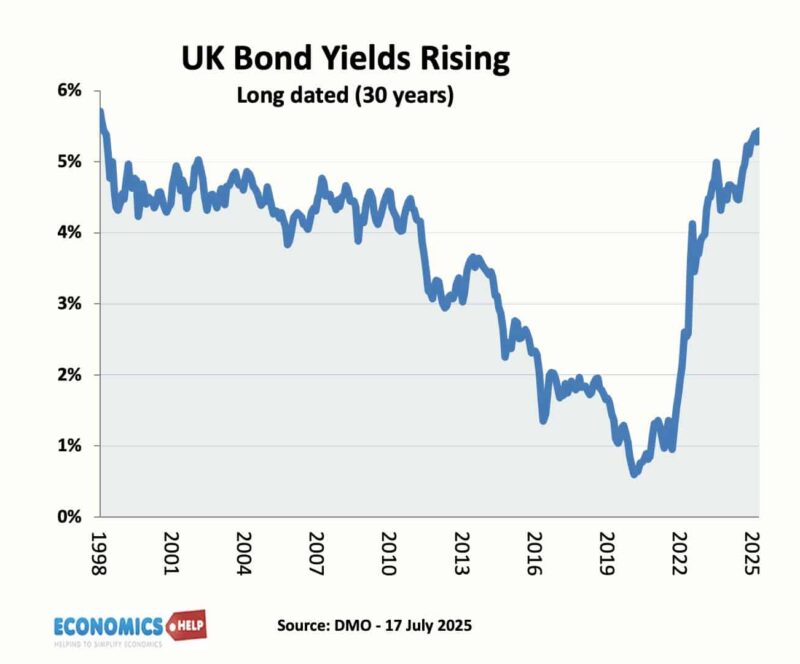

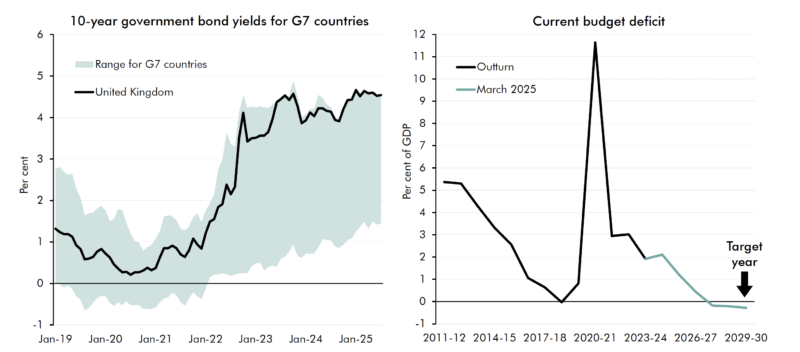

It’s not been as spectacular as September 2022 when bond yields made the front pages, but quietly markets are pushing up the cost of UK debt.

The bond yield for 30-year gilts has reached its highest level since 1998. You might think – Why does this matter to me? But this is partly a vote of no confidence in UK finances, and as bond yields rise, government spending on debt interest rises, which creates an unwelcome need to raise taxes just to pay interest cost.

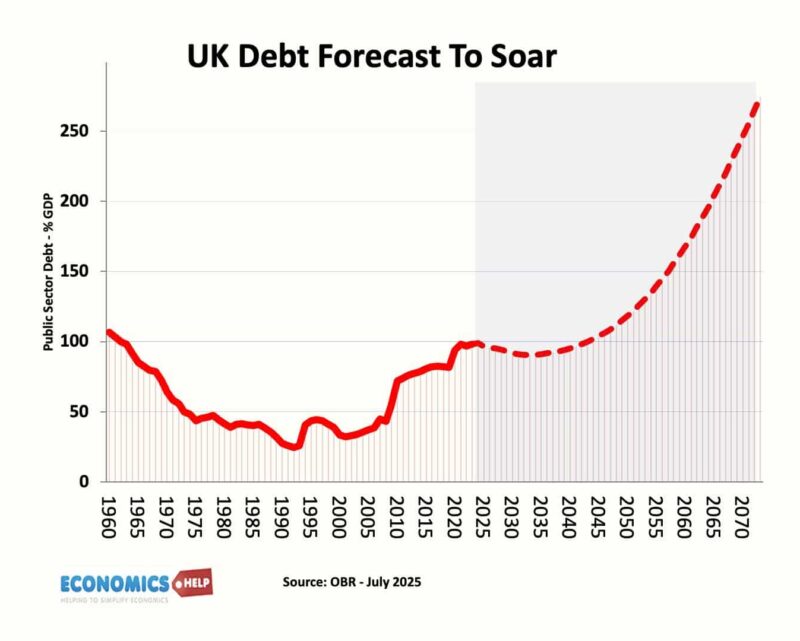

If the fiscal situation looks grim now, the long-term forecasts are worse. The OBR suggest on current trajectory, debt will be 270% of GDP by 2073. But, even that dire forecast seems rather optimistic that debt will fall over the next few years. With borrowing persistently coming in higher than expected, it is quite possible debt will rise sooner.

A few years ago, the UK could afford to run a budget deficit and still stabilise government debt as a share of GDP. But, because of lower growth, higher inflation and higher interest rates that relatively benign situation has been lost. We are heading towards a situation where the proportion of taxes on debt interest could rise from 7% towards 14% of all tax revenue. And that means you would need to run budget surpluses just to stabilise debt as a share of GDP.

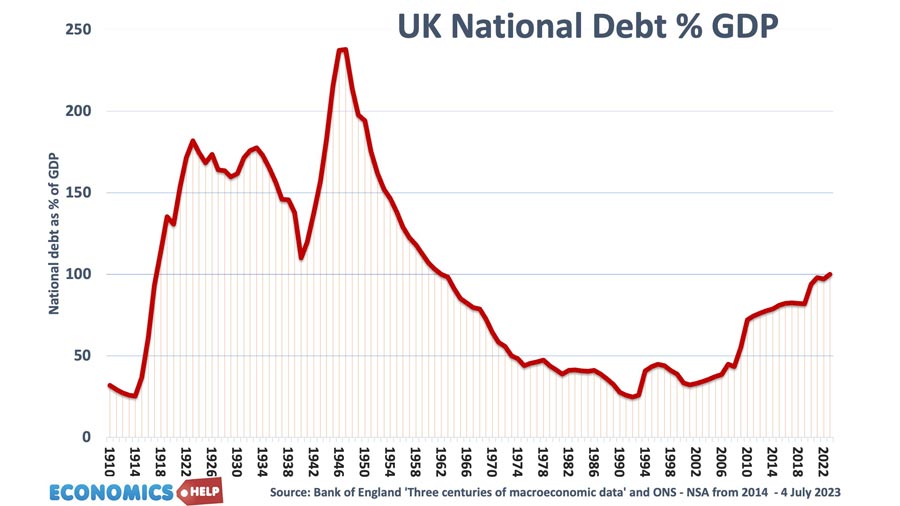

Falling Debt in post-war period

In the post-war period, high rates of growth led to falling debt as a share of GDP, even though the government mostly ran budget deficits. In the aftermath of the 2010s, the economy stagnated meaning that tax revenues were disappointing. But, as compensation, interest rates were cut to 0.5% and gilt yields fell to record lows. It was very cheap to borrow. Not only that but the Bank of England created money to buy gilts. Selling gilts had never been so easy. With borrowing so cheap, it was something of a missed opportunity to invest in things holding back the UK economy like housing and energy costs, but public sector investment was a key target of austerity. Another forward-looking strategy would have been to sell 30 year gilts to lock in the super low gilt yields. But, unfortunately, in recent years, the UK has actually moved from long-term dated gilts to much shorter term gilts. Short-term gilts, means that you keep have to refinancing the debt more frequently, so if interest rates go up, the government faces the higher interest payments sooner. The Debt Management office also sold a lot of inflation-index linked bonds, assuming inflation was over, this is one reason why debt interest payments soared with the return of inflation in 2022.

Reversal of QE

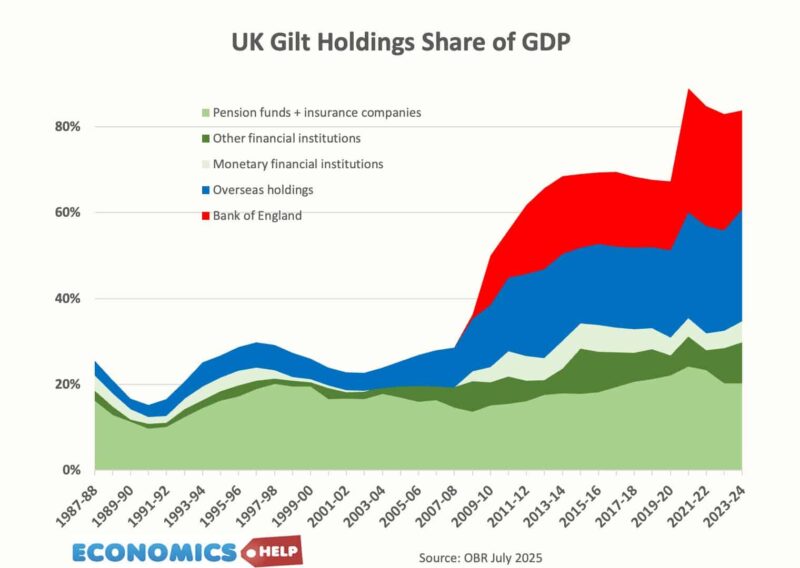

In 2025, the government faces many challenges. Firstly, the Bank of England is reversing quantitative easing. This means the Bank is selling additional gilts onto the market. Not only is the Bank selling gilts, it is selling at a loss. It bought bonds in 2020 when interest rates are low. But, the rise in bond yields means the value of bonds has fallen. A gilt maturing in 2061 was worth £96 in 2021, today it is trading at £25. And when the Bank of England sells at a loss, the loss is absorbed by the Treasury, i.e. the tax payer. There is a good case for halting the reversal of QE, at the very least just let the gilts mature rather than sell at a loss.

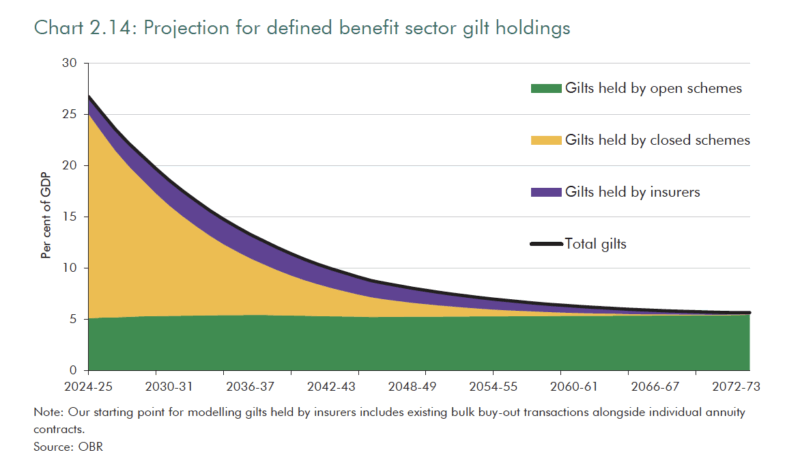

If you look at who owns government gilts, you can see the Bank of England holdings went from 0 to 22% of GDP in the last decade. But, these are set to be all sold off. But, there is more bad news in the gilt market. In the 1990s, over 60% of gilts were held by UK pension and insurance funds. But, the OBR predict that gilt holdings by pension funds will fall from 30% of GDP in 2025 to 11% in 2074.

Pensions used to be predominantly benefit defined, i.e. pension gave guaranteed income, and this made gilts with their definite interest payments attractive. But, the modern preference is for contribution based pension funds. These tend to invest in equities and invest much less in bonds The FT report that this shift from pension funds could raise overall interest rates on UK debt by around 0.8%. By the way as a rough rule of thumb for every 1 percentage point rise in gilt yields across the yield curve adds an extra £20bn in interest payments or if you prefer an extra 3.5p on the basic rate of income tax.

Who will buy UK Debt?

So if the Bank of England is selling and pension funds are less keen to buy, who will buy UK debt? Increasingly, we will rely on foreign overseas holders. They already account for nearly 30% of GDP. But, there is a drawback to relying on foreign buyers. The value of the Pound becomes more important. If the pound falls, foreign investors will want to sell. Also, the UK will need to offer higher bond yields to attract foreign buyers. And by the way, the UK will face a lot of international competition. It’s not just the UK experiencing a rise in debt. The biggest shock of 2025 has been the rise in Japanese bond yields though the UK has the highest bond yields in the G7.

But perhaps the biggest problem facing the UK bond market is that no one really wants to pay to fix Britain. Firstly, the number of working age adults to retired will fall around 30%. This will cause a projected rise in both health care and pensions as a share of GDP. The triple lock pension guarantee has already been £15bn more expensive than expected, and depending on the volatility of inflation the state pension could rise to 9% of GDP by 2070. That would be over 20% of tax revenue on state pensions. The pension triple lock also creates a lot of uncertainty about future revenues and future pensions. However, with over a third of voters over the age of 65, it is pretty big block of voters, especially when in the UK you can theoretically win a majority with 34% of the vote. Defense spending as a share of GDP is also supposed to rise, and the UK is also seeing a sharp rise in working age health related benefits too. But, the problem is that once a benefit is in place, it is hard to take it away. Winter fuel allowance was a temporary measure at a time when the state pension was much lower. Yet, trying to take it away was a political disaster.

SEND

In the 2010s, there was an expansion of special needs education with the legal right for parents to get school of choice. But the percentage diagnosed with special needs has soared beyond expectations. Local councils don’t have enough places and are spending up to £61,500 per pupil paying for private provision and taxis for transport if necessary. Unsurprisingly, combined with rising social care bills, it is bankrupting local councils. The government tried relatively modest efforts to limit the growth in some spending, but largely failed. Reform, the party currently leading the opinion polls have pledged very large tax cuts up to £80bn a year – tax cuts mostly favouring richer housholds. The tax cuts which will be financed by what the IFS call large unspecified spending cuts. It is somewhat reminiscent of the Truss budget.

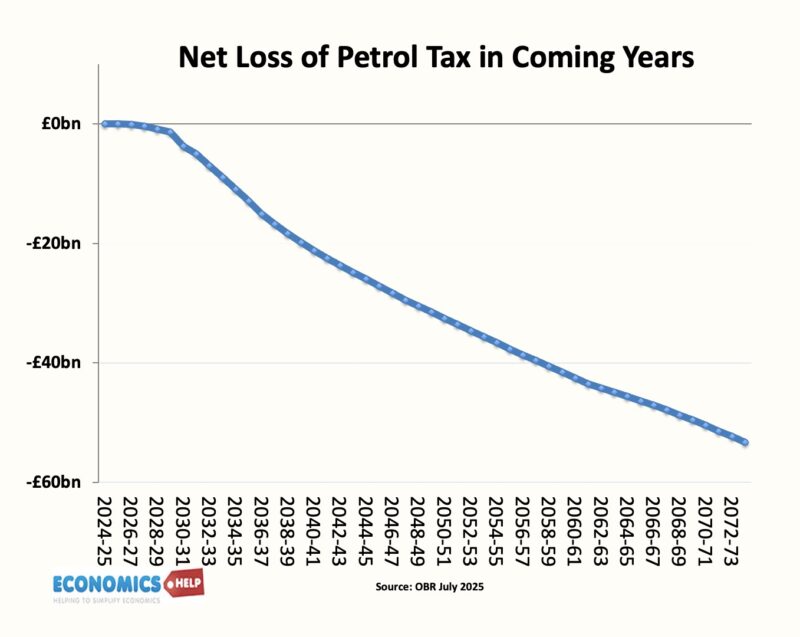

Falling Tax Revenue

Not only is spending rising, but tax revenue is also set to fall too. Petrol tax revenue is set to evaporate, leading to £56bn less revenue. Tobacco tax is set to fall too. (Inheritance tax is set to rise because of large wealth transfer) A solution would be to introduce electronic road pricing, but would voters welcome a new tax?

I could go on and on about fiscal pressures facing the country, but you get the idea. Of more interest is what could be done about it.

Wealth Tax

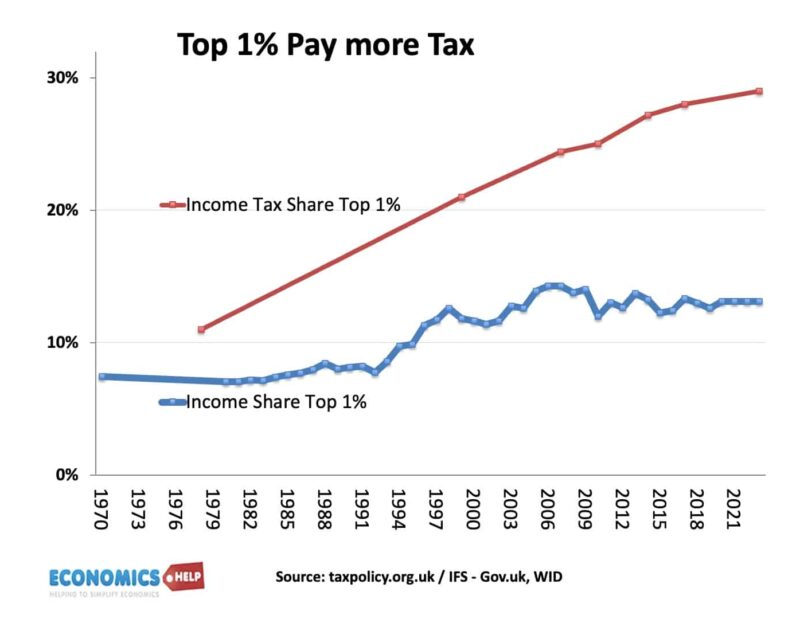

The first is tax the rich. How can the UK be living beyond its means when wealth has gone up so much. Some point to a wealth tax. E.g. 1% wealth tax on wealth over £10 million could raise an estimated £12 bn a year. Firstly, wealth taxes are administratively hard to implement, and £12bn is not very much, the kind of sum that could be wiped out by bond yields rising 0.6 percentage points. Although fears of a wealth exodus are greatly exaggerated by the media, a French wealth tax did lead to very disappointing revenue because it was easy for the French to relocate to Belgium and Monaco. There is a reason very few countries have a wealth tax, and even those who do, raise very small sums. Due to more inequality, the income share of the top 1% has increased from 8% in 1978 to 12% in 2022. However, the income tax share paid by top 1% has increased from 11% to 28% in 2022. Ironically, in some respects the UK tax system has become more progressive in the past four decades. The share the richest 20% pay has increased from 36.2% to 46.8%

So you could get some more out of the top 1 and top 10%, but it would not be easy to generate the sums the UK needs. If you look at countries with big welfare state and more generous state pensions like Scandanavia, they usually rely on higher broad based taxes like VAT rates of 25%. The real challenge for raising taxes from the top 0.1% is actually finding where the money is hidden. But taxing the rich would not be a panacea to the UK’s problems.

Policy Commissions

What the UK does need is indepth policy commissions, ideally with cross party support. For example, the 2002 pension commission arguably did a good job in improving private pension enrollment, raising state pensions, but with a trade off of raising retirement age. The reforms included both costs and benefits, but it is easier to get something through when there is a sense of long-term planning rather than panicking to meet the latest OBR thrice yearly forecast. The government have announced a new pension commission, although they have kept the triple lock off the table. The UK needs many such commissions from tax to welfare and education.

When looking at debt, it is always helpful to look at historical comparision. Debt has been much higher in the past. But, I would argue that is of limited comparison. After a war, you can easily cut government spending – defense spending can shrink. Also the post-war period of high growth seems to be deserting the UK. We also now have very different demographics, which is a big factor behind rise in debt.

I usually try to end videos with a more optimistic take. But, it is harder to find perhaps there is a chance governments get lucky with higher growth and lower interest rates. But the fiscal challenge is genuinely quite big. One final point – what about QE and creating money, does this cause inflation? – This video goes into a lot of detail on this tricky, but interesting question.

Sources

https://www.ft.com/content/261fa8ce-47a8-4180-870e-82331b61d03a?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://www.ft.com/content/8b5fe097-413b-4c7e-958c-61fadae91608

https://www.tes.com/magazine/analysis/general/how-many-school-pupils-have-send-ehcps

https://freethinkecon.wordpress.com/2025/07/15/there-really-is-no-getting-out-of-this-fiscal-corner/