Readers Question: Can you Spend Your Way to Full Employment?

Full employment implies.

- An economy without a significant negative output gap. Full employment requires positive economic growth, averaging close to the long run trend rate of economic growth. (in UK long run trend rate = 2.5%)

- Very low unemployment. Economists would say full employment is an unemployment rate of less than 2 or 3%. This 2 or 3% would be just the inevitable frictional unemployment.

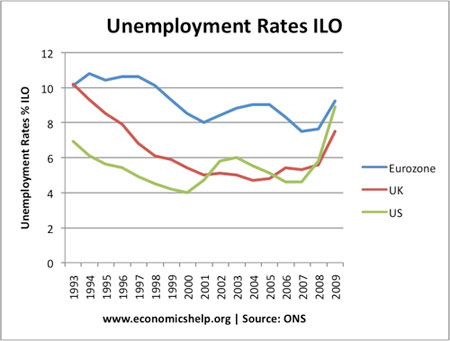

Currently, all major economies are a long way from full employment. Unemployment rates are close to 10% and recent years of negative or low growth have left an output gap.

How Spending can Create Full Employment.

Demand deficient unemployment occurs when there is a fall in aggregate demand leading to negative economic growth. As output fall, firms employ less workers. In this situation of falling output and low confidence, individuals are more likely to save and reduce their own spending. (paradox of thrift)

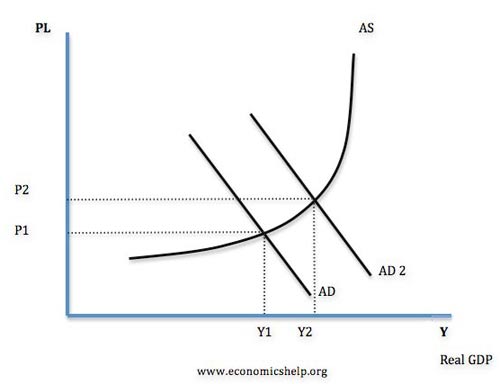

It is argued that if there is a rise in private sector saving and fall in private sector spending, the government can offset this fall in demand by spending more. The government can run a short term budget deficit and increase government spending. This government creates additional demand in the economy and leads to higher economic growth. As the economy recovers firms will employ more workers.

Government Spending on Increasing AD

Evaluation

- The increase in government spending may need to be very substantial. If GDP falls 6%, to correct the fall in spending, the overall increase in government spending required may be substantial.

- Crowding Out. Some economists argue that higher government spending leads to crowding out. Higher government borrowing can lead to higher interest rates; this leads to lower spending. Also, if the government spend more, it means the private sector has less funds for private sector investment.

- – However, if the private sector don’t want to spend, but are saving more then crowding out shouldn’t occur. For example, since 2008, UK and US debt have increased but interest rates on government debt has fallen (US debt). This is because in the current climate private sector are wanting to save more. Therefore, higher government borrowing doesn’t always lead to higher interest rates. Therefore, in a liquidity trap / recession there is little or no crowding out.

- Overall debt. A crucial issue is overall debt. If private sector debt falls because the private sector saves more, then an increase in government borrowing is not actually increasing overall debt in the economy. However, if the government borrowed to spend during a period of strong economic growth, then crowding out would be likely to occur.

- Fears of Debt Default. Countries in the Euro have experienced concerns over liquidity (partly due to being in the Euro). Therefore, they have much less scope for increasing government borrowing and spending their way out of a recession.

- Not Just Government Spending. Increasing government spending may have limited impact if the country is experiencing deflation and low expectations of growth. In this situation, increasing government spending may still fail to stimulate spending, e.g. Japan’s budget deficits failed to overcome output gap because they experienced deflation. Therefore, government spending may also require suitable monetary policies.

- Inflation Fears. On the other hand, if government spend too much, there is a danger of inflationary pressures, e.g. if AD increases faster than AS.

- Supply side unemployment. Higher spending can tackle demand deficient unemployment; in theory it can help boost economic growth. However, it will not tackle structural unemployment – e.g. unemployment due to lack of skills, geographical unemployment, poor information e.t.c. This type of unemployment will require supply side changes which make labour markets more flexible.

Related