Ever since the Euro debt crisis hit the headlines in 2008, economists have argued that the ECB need to act and buy bonds to prevent liquidity fears and prevent bond yields from being artificially high.

Held back by fears of the ECB exceeding their mandate, we have watched in despair, as bond yields on Eurozone economies have risen to damaging levels. The unwillingness of the ECB to act as lender of last resort has meant the Euro project has a deep structural flaw.

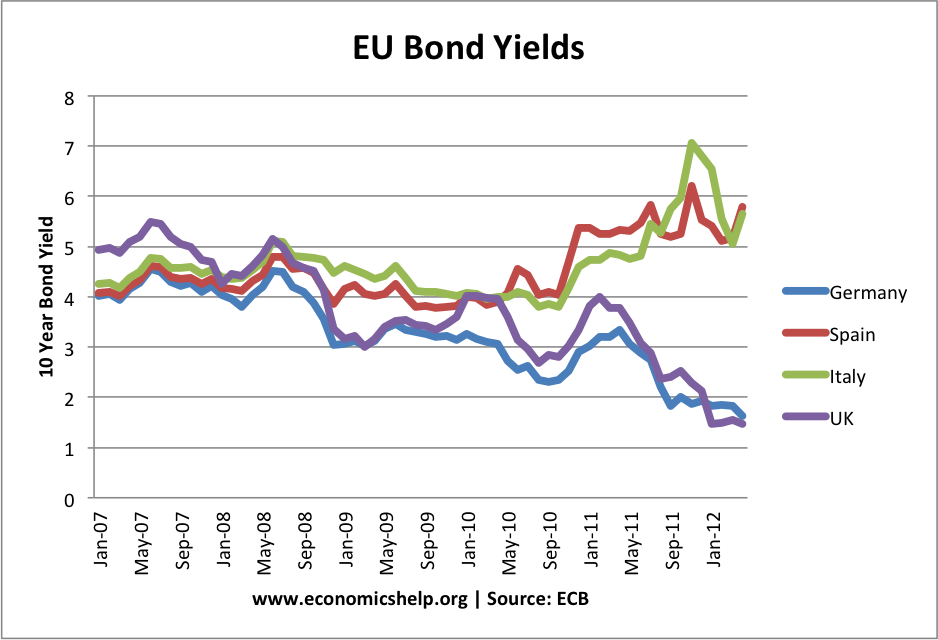

To take one example, Italy has a primary budget surplus. It has a lower level of indebtedness than the UK, but Italian bond yields have risen close to danger levels of 7% – whilst UK bond yields have fallen to 1.5%.

The consequence of this liquidity crisis is that Italy have been forced into excessive levels of austerity (spending cuts and tax rises). Yet, with bond yields at 7%, these austerity policies have been self-defeating. Debt to GDP ratios have failed to fall satisfactorily. Furthermore, markets have become worried about the fall in economic growth that austerity and overvalued exchange rates have caused. Markets can’t see how countries can attain sustainable reductions in debt to GDP when:

- The cost of borrowing is close to 7%.

- Austerity measures are creating a damaging deflationary spiral.

Bond Yields and Market Failure

Bond yields of 7% in Italy and Spain are a classic example of market failure. Because there has been no lender of last resort, markets fear a liquidity crisis. Confidence has evaporated. It means borrowing costs have become prohibitively expensive – making the task of deficit reduction much more difficult.

This below calculation is a very rough – but it does give an idea of the importance of bond yields to a government’s fiscal position.

- The UK is paying £43bn a year in debt interest payments on UK national debt. This is with a 10 year bond yield of 1.5%.

- If bond yields were 7% – our debt interest payments would be much higher – say over £100bn a year. That means we would have to find an extra £50 – £60bn of spending cuts – just to finance higher debt interest payments caused by higher bond yields.

- The UK’s effort to reduce long term debt commitments is definitely helped by a Central Bank willing to act as lender of last resort to the government and the consequent low bond yields.

The UK economy has suffered through much more moderate spending cuts. If we had faced bond yields over 7% and even stricter austerity policies, the UK economy would be in much deeper recession.

Will Unlimited Bond Purchases reduce bond yields?

- In the past, ECB bond purchases have been temporary / conditional – these bond purchases have failed to change market sentiment. After brief ECB interventions, bond yields returned to their former level.

- Now, if there really is unlimited bond purchases, then the ECB should be more effective in reducing bond yields.

Why Have Economists (mainly German) Opposed Unlimited Bond Purchases?

- With experience of hyper-inflation in the 1920s, Germany has always been fearful of monetary policy which could create inflation. Unlimited bond purchases, through creating money – have the potential to cause inflation. Though the policies of Quantitative Easing in UK and US have failed to cause any real inflationary pressure. These unlimited bond purchases will be sterilised – meaning there should be no increase in the money supply.

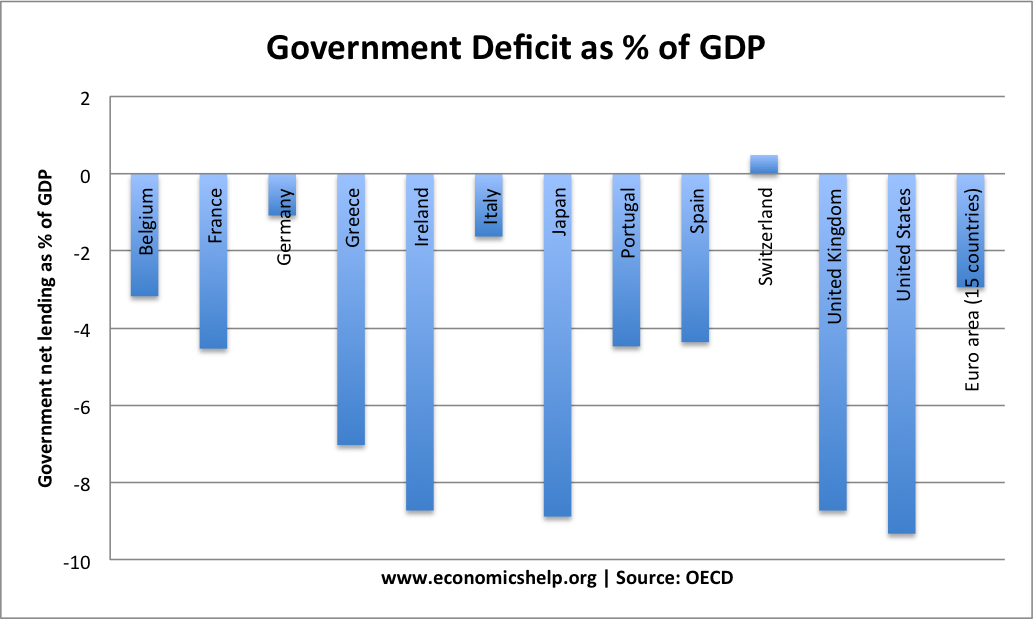

- Moral Hazard. From a German perspective, unlimited bond purchases could be seen as a way of rewarding profligate public spending. If countries run up debt, then they can rely on the ECB buying bond purchases to keep bond yields artificially low. If this happens there is an incentive to borrow because bond purchases will keep bond yields low. Therefore, there is a definite sentiment that countries with high debt levels – need that punishment of higher bond yields.

- Bond purchases arguably exceed the remit of ECB. There is a danger of making ECB a political body – e.g. which country will they save?

Why have the ECB changed their mind and started to Buy unlimited Bonds?

- The argument of moral hazard is fairly weak. Higher bond yields are a response to the exceptional situation we find ourselves in. Bond yields are much higher than debt levels would suggest. e.g. compare Spanish and UK debt levels at the start of the crisis, and there is no logic for difference in comparative bond yields.

- The Euro could collapse without decisive intervention. All previous half-hearted attempts at intervention have essentially failed. If the ECB want to save the Euro – which they do, then unlimited bond purchases has become a necessity.

- In the ECB, there is some concern at the descent into a double dip recession (though there should be much more concern). Austerity policies are creating mass unemployment and social instability in southern Europe. There is also a recognition of the self-defeating nature of austerity. Spending cuts have done nothing to solve the debt crisis in Greece, Italy and Spain. More austerity wouldn’t solve the problem.

- Even if you want to ‘punish’ ‘profligate’ spenders, bond yields of 7% are much more than necessary.

- The whole idea of the Eurozone is that countries would have the same interest rate and similar access to bond markets.

Will Bond Purchases Save the Eurozone Economy?

- Probably not. The Eurostat said GDP in the euro area fell 0.2% in the second quarter from the first, and 0.5% from a year earlier, confirming the region is already in recession.

- Countries are only eligible for unlimited bond purchases when they commit to a precautionary programme of sound finance. This is not quite as strict as previously, but for all practical purposes, countries have to be in bad shape before they are eligible for bond purchases.

- These bond purchases are essentially aimed at removing distortions in the bond market. They are not seen as unconventional expansionary monetary policy.

- The EU has no real policy to overturn the overwhelming deflationary pressures in the Eurozone. Inflation expectations continue to fall, leaving higher debt burdens and deflationary pressures in the economy.

- It will not tackle the growing credit crunch and capital flight in southern Europe.

Conclusion

Yes, this will help. But, why didn’t the ECB do this three or four years ago? It is also not enough. There has to be a willingness to pursue unconventional monetary policy aiming to reflate the stagnant European economy. Also, it doesn’t deal with the fundamental problem of uncompetitiveness within the Euro single currency. It is not a panacea to the structural weaknesses of the Euro. But, it will probably keep the Euro together for longer.

Related