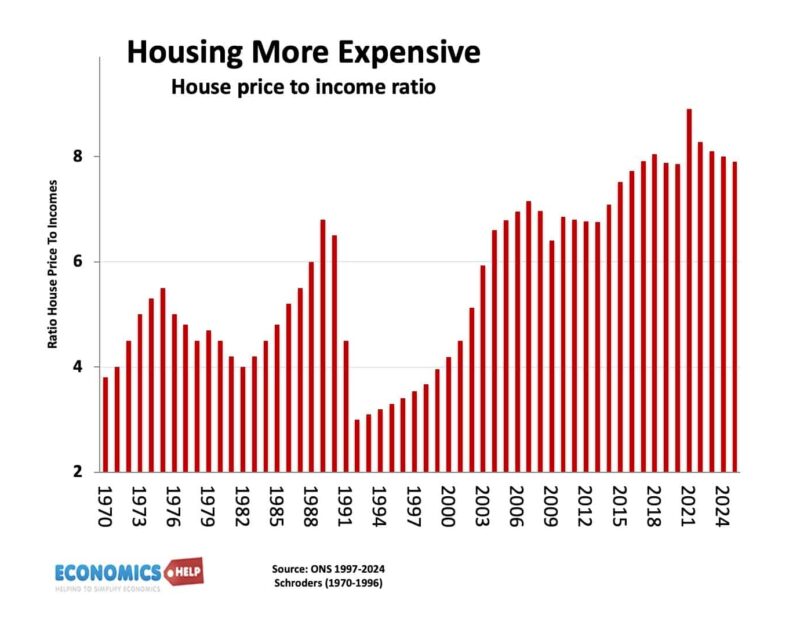

In the early 1980s, housing was around 4 times income, but today, a buyer will need 8 times their income. Young people cannot afford to buy, with average deposits running at over £60,000. Renting has also soared in recent years, with average rents nearly £1,400 a month in England, and £2,200 in London. In the past several years, we’ve seen countless initiatives which have all failed to address this problem. Why is it so hard to make housing affordable? And what would it take to fix the crisis?

Interest Rates

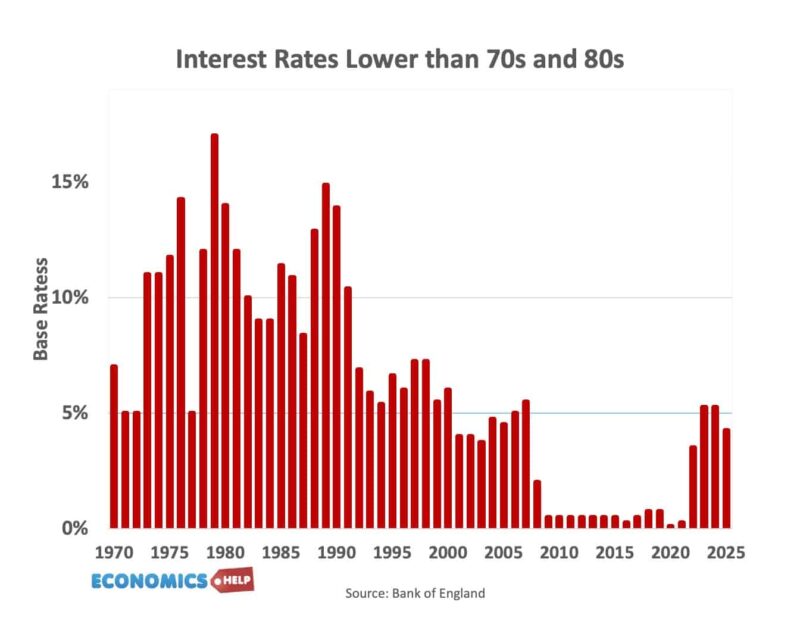

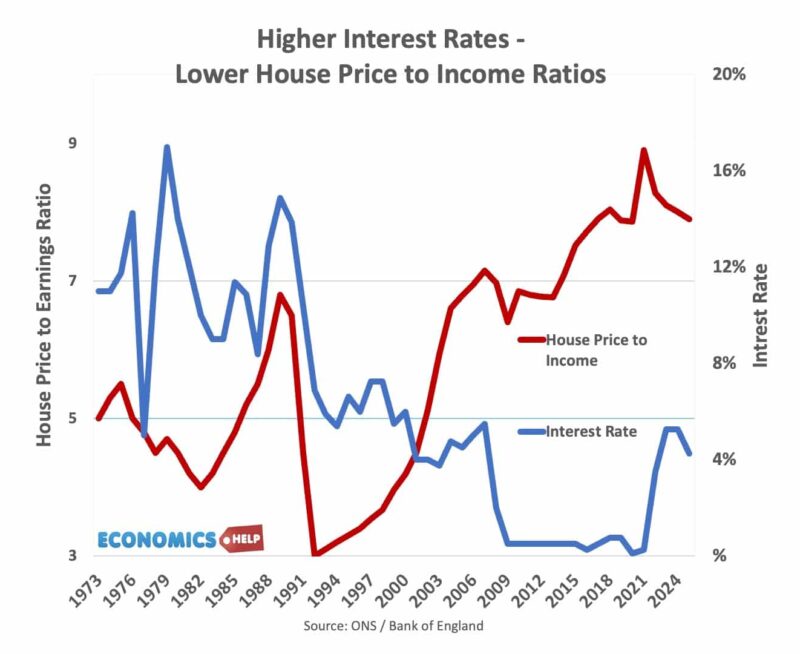

Firstly, when house prices to income ratios were very low in the 1970s and early 1980s, interest rates and mortgage payments were higher. When interest rates fell in the mid 1990s and mid 2010s house price to income ratios soared. It is a little crude but when interest rates are high, house prices tend to be lower. When interest rates fall, house prices to income ratios rise.

In 2022, interest rates rose and as a share of income, mortgage payments rose to levels close to previous crashes. It was worst of both worlds – high prices and high monthly mortgage payments. But, since then slightly lower interest rates are once again seeing a modest recovery in house prices. And this is the problem, as soon as mortgage rates go down, there is large pent up demand which tends to push up prices. The only time we had low house prices and low interest rates was the mid 1990s, but this caused a real boom in house prices.

One reason for high house prices, especially in certain regions is that supply is inelastic, it can’t easily respond to demand. The past 20 years is a time of house building continuously failing to meet government targets. The current government targets of 1.5 million would require the highest level of homebuilding since the early 1970s, but last year builds were nearly 50% less than the government target. To double the effective house building rates would take a monumental effort. Building companies claim even if planning restrictions are lessened there is a lack of skilled builders. In addition, they have little profit incentive to build enough houses to reduce prices and therefore reduce profits. They would often rather hang on to plots with planning permissions and not actually build anything. Some claim there are over 1 million plots with planning permission yet to start building.

Supply

But, even if the government were to build 1.5 million homes, would prices suddenly become affordable? Don’t hold your breath. A 1% rise in supply might reduce prices 1.5%. If you build 300,000 homes every year for 20 years, this would mean prices would be 10% less than otherwise. But some claim the UK has a comparable housing shortage of over 4 million, we have certainly built a lot less than comparable European countries in recent decades. To address this shortfall would take decades. Also, any government with the well-meaning intention to build more houses will come across the political reality that many people don’t want houses or flats to be built in their area. Sadiq Khan initially had a target of 35,000 affordable homes to be built in London, but these targets have been slashed after failing to get anywhere close. The problem is affordable housing is less profitable for builders, and the government lacks sufficient funds to build housing. But, also when affordable housing projects are suggested, councils may turn it down anyway. For example, this housing project in Battersea would have provided 50% affordable homes, but residents didn’t like it and it was blocked. If you want affordable housing, it tends to need housing density, but the UK is not keen on tower blocks, the 60s council blocks contributing to a persistant bad image.

Immigration

Given housing is so difficult to build, what are the other options to reduce price. One factor, behind the rise in housing demand is the growth in the population, largely fuelled by net migration. Since 2022, cumulative net migration totaled 2.5 million or about 1 million households, this is far higher than the ability to increase the housing stock and has had an inevitable impact on increasing rent demand and rent inflation. Despite higher cost of living and stagnant real wages, rents have risen by 24% in just three years. Reducing net migration to more manageable levels would help moderate demand. But, there are also drawbacks of cutting migration. OBR forecast low migration would lead to higher government borrowing. Low migration may make it difficult to recruit skilled bricklayers needed to build houses. Also, even if net migration was cut to zero, like increasing supply, it would take time to lead to lower house prices.

Benefits

Another reason behind the UK having high rate of unaffordable housing is that despite rising rents, housing benefits have been frozen, meaning that the share of private rentals which are affordable for those on housing benefits has fallen from 12% in 2021 to just 2.5% in 2025. One of the quickest solutions to make housing more affordable is uprating housing benefit to past levels, but given state of finances and pressure on budget, the government is very unlikely to do that.

Council Homes

In the 1970s and early 1980s, there was a much higher share of council properties to the population. This meant very low income households had the option of below market rents, which kept housing affordable for the poorest households. But, since 1980, 1.5 million council homes have been sold, without replacing them. It means the stock of council houses fell, even as the population rose. This has pushed more people into the private rented sector, which is another factor pushing up prices. The problem is with budgets squeezed there is not enough funds for government to directly build substantial numbers of homes.

Maximum Prices

One solution to high rents is maximum prices. It was briefly tried in Scotland and Sadiq Khan has intimated he would like to try in London. Even a fairly modest rent cap in Scotland introduced in 2022 saw landlords claim 22,000 left the market and upcoming maximum rents is a factor behind the 26% fall in new build to rent construction in the last year. To some extent the government face an unwelcome choice, rent caps, which are good for some renters, but create a shortage for other tenants who have less choice.

Help To Buy

Given the unaffordability of housing, a popular government response has been help to buy. This gave help with deposits for first time buyers. 385,000 benefited from help to buy, with £24 bn of loans and £109bn of property purchases. But, this was like trying to put out a fire by putting on more wood. It led to higher demand, and higher prices, it is not a long term solution. Since its end, there are other schemes such as shared ownership, lifetime ISAs and mortgage guarantee scheme. There will probably be more variants, but the solution is basically about helping people to buy, but the more successful they are in helping, the more demand rises and the more prices rises.

Wealth

A much bigger help to buying is not from the government but family and parents. Last year, a record amount of money was lent to help children buy a house. UK finance suggests this is causing a big disparity in buying power. Unassisted buyers had an average deposit of £61,000 and average income of £65,000. Assissted buyers had an average deposit of £118,000 and an average income of £55,000. For many this has become the main rung to get on the property ladder. It is one reason behind the long-term rise in house price to income ratios. Wealth is effectively recycled back into inflating the housing market, pushing up prices and sustaining permanently higher prices. The only solution would be to tax lifetime transfers. Kind of inheritance tax before you even die. Unlikely to be popular.

Second Homes

Doubling or tripling council tax on second, unoccupied homes could help to reduce prices in tourist hotspots and perhaps London. The UK has an estimated 1 million vacant homes the highest level in 10+ years.

It is good to look at cities which have reduced rents. In the US Minneapolis with most new dwelling approvals and biggest drop in rents. The biggest rises came from cities with lowest approvals. You can see similar results in Auckland, New Zealand and the rented sector in Austin, Texas. So the good news is that lower rents are possible. But, it is not without drawbacks. It does lead to the necessity of building more. And if you want to build more, there is need for restrictions on height, density.

Another way to get cheaper housing is to make it cheaper to buy, less environmental regulations like nitrate levels in water. But, again, there is trade off in terms of worse insulation and environmental costs.

The other aspect of affordability is income. Real house prices have actually fallen since 2009, but with stagnant real wages, many struggle to buy. But, increasing incomes is much easier said than done.

A long term solution is high density council housing, but in a way that doesn’t repeat the mistakes of the 1960s tower blocks.

No easy solution because everything policy has trade offs, but there are some things that will help. What is going to happen to house prices, are we facing another boom?

Texas, Auckland had much looser regulations, aloowing for rezoning and

https://www.scottishhousingnews.com/articles/landlords-blame-drop-of-22000-homes-to-rent-on-government-policy-and-rhetoric

At the end of last year, an average first time buyer needed to pay paid a deposit of £61,000

https://www.finder.com/uk/mortgages/first-time-buyer-statistics?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Build, build, build