Definition of creative destruction This refers to the process of how capitalism leads to a constantly changing structure of the economy. Old industries and firms, which are no longer profitable, close down enabling the resources (capital and labour) to move into more productive processes.

Creative destruction means that the company closures and job losses are good for the long-term well-being of the economy.

It can be seen from both a negative and positive perspective.

Creative destruction and Marxism

Karl Marx wrote at length about the nature of capitalism causing large-scale loss, which enabled new wealth to be created. Marx saw wars and economic crisis as methods for destroying production and enabling capitalism to start a new round of wealth creation for the owners. Although Marx saw how Capitalism could reinvent itself, he also felt it’s inherent tendency to self-destruction would eventually lead to its end.

“In these crises, a great part not only of existing production, but also of previously created productive forces, are periodically destroyed.”

– Karl Marx, Communist Manifesto

Creative destruction and Schumpeter

Joseph Schumpeter popularised the concept of creative destruction in ‘Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy‘ (1942). He used the phrase ‘gale of Creative Destruction’ and the concept is sometimes known as Schumpeter’s Gale. He derived his ideas from a close reading of Marx. However, whilst Marx believed capitalists crisis and destruction would lead to its demise, Schumpeter saw creative destruction as a necessary and natural way to enable new markets and new growth.

“Capitalism […] is by nature a form or method of economic change and not only never is but never can be stationary. […] The fundamental impulse that sets and keeps the capitalist engine in motion comes from the new consumers’ goods, the new methods of production or transportation, the new markets, the new forms of industrial organization that capitalist enterprise creates.”

– Joseph Schumpeter, ‘Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy‘ (1942)

Creative destruction and laissez-faire economics.

Ironically, for a concept derived from Marxist thought, free-market economists have seen creative destruction as a necessary and inevitable process of economic development and generally oppose government attempts to hold back this process of decline and renewal. Some economists even go so far as to argue that if banks fail, the government should not intervene as it is better to allow bad banks to fail and avoid the government artificially propping up the financial system.

Free market justification for creative destruction

- If a firm becomes unprofitable, then it should close down so that resources, (labour and capital) can move into more productive and profitable firms and industries. Without this willingness to change, we might have got stuck with Nineteenth Century living standards.

- The threat of going out of business is an incentive for firms to move with the changing market and keep costs low. For example, in an electronic age, newspapers are needing to re-invent themselves with an online presence.

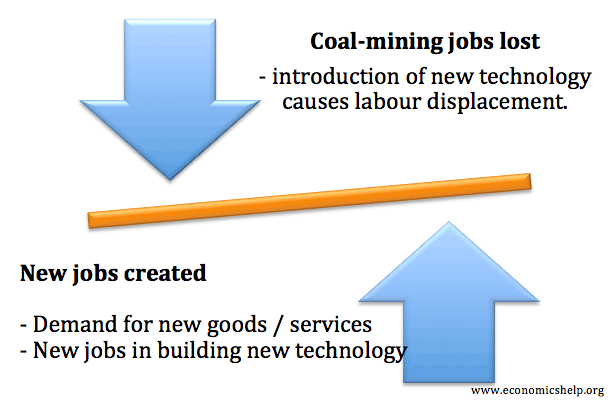

- Although short-term job losses are bad for those involved, people often forget the less visible new jobs created during the economic change. In the long-term, periods of labour market change have enabled rising real wages.

- In 1920, over 1 million worked in British coal industry, now there are just a few thousand. This shift in labour has enabled the growth of new industries and firms in the service sector, enabling better standards of living.

Examples of creative destruction

Powered looms. The invention of the steam-powered loom reduced the cost of making clothes. This put the traditional cottage industries out of business. But, it helped a new industry of manufactured cotton and clothes which created new kinds of jobs. (This particular invention led to the Luddites, who saw the new power looms as destroying their livelihoods)

The large mills which once dominated the towns of northern England have now closed down due to cheaper imports from Asia. As the mills have closed down, the local economy has been more geared towards the service sector and less towards manufacturing.

Music

The music industry has seen numerous technological changes which have led to the rise and fall of several companies.

- In the early 1980s, the cassette started to overtake vinyl, harming firms which relied on the manufacturer of vinyl. But the early 1990s, the compact disc had started to replace the cassette. For a short period, the compact disc was very profitable for record labels and manufacturers, such as Phillips and Sony.

- However, from the early 2000s, electronic downloads wiped out the profitability of compact disc manufacturer and sale, creating a very different music industry, dominated by digital downloads and new companies like Napster and Apple taking the place of other more traditional music companies.

The problems of creative destruction

Free-market economics makes a case for allowing any unprofitable firm to go out of business whatever the consequences. However, some argue that the process of creative destruction can lead to long-term damage and needs to be more carefully managed.

- Structural unemployment. When some industries close down, there is no guarantee the unemployed workers will be sufficiently skilled to shift employment prospects. At the very least, there may be a need for government intervention to give better skills to the long-term unemployed.

- The firm industry may provide external benefits which impact on social efficiency. For example, in the 1960s, the Beeching report advocated closure of many UK railways because the car was more efficient. It was a classic example of creative destruction – close railways and invest in roads. However, 40 years later many rail closures are regretted because railways can help reduce road congestion, pollution, plus no-body predicted the increase in rail demand of the past 20 years.

- Regional unemployment. In a shifting economy, regional immobilities can make the ‘destruction phrase’ last for a long time. A large-scale closure and the loss of many jobs can be difficult for an area to deal with. New jobs may be created in the economy, but not in the area of high unemployment. This can lead to a prolonged period of low growth and high regional unemployment.

- Winner and losers. In the process of creative destruction, some will benefit a lot, but others may lose out, e.g. long-term unemployed struggling to shift occupation. It is not a Pareto improvement.

- Closure can lead to inefficiency itself. If a firm with experience and investment in human and labour capital closes down, then it can take a long time for these resources to be efficiently redistributed. For example, the theory of hysteresis, suggests short-term unemployment can lead to a higher natural rate.

- Unprofitability doesn’t mean the firm always should close down. Market forces may lead to many firms closing down because of lack of profitability. However, this closure may not be an efficient outcome. A firm may become unprofitable from short-term factors, such as

- High tariffs hitting exports

- Short-term recession hits output

- Short-term labour market problems, such as strikes

- A temporary glut in supply from overseas.

- See bailout of US car industry

In these cases, the lack of profitability is not a sign the firm is terminally inefficient. In these cases, there may be a strong case for temporary government help to enable the firm to come through the short-term difficulties. It may also be possible for a firm to restructure and diversify – this can be less damaging than wholesale closure.

Similarity with Luddite fallacy

The Luddites protested against the introduction of new machines which took the jobs of skilled artisans. However, although jobs were lost in hand-spinning – new jobs were created in other areas of the economy.

Related

Nice summary. We need to respect the virtue and necessity of destructive Schumpeterian “gales”. Modern “Safety Nazism” (a term first used by the Auto industry in the 1970’s), has become a dominate objective of Government policy. It this wise? Consider the chart, showing “coal mining jobs lost” vs “new jobs created”. It is asymetric, is it not? “Mining jobs lost” = several thousand, while “New jobs created because of the internet” = several 10’s of millions, no? I am not saying we should blow up things, but an understanding of what Schumpeter and others have said, suggests that an aggressive reduction in the scale, extent and cost of delivering “government”, would probably lead to both a somewhat more dangerous world, but also one in which there is *much* greater opportunity and self-stimulating economic growth. And the current expansion underway in USA (which contrasts to the stagnation and drift in hyper-social-welfare oriented Canada, for example), seems to bear out the truth of assertion that “Less is More”, when it comes to the toxicity of constant expansion of the non-self-financed “Government” sector. In Canada, despite our skills and factor endowments, we still run poorer and with typically double the rate of unemployment and half the rate of economic growth that our neighbours to the south enjoy. We constrain Schumpeter’s “gales” here, and we protect and restrict just about all human action here as well. This is perhaps an unwise strategy, which has been pushed too far, and needs to change, lest we choke on regulations and restrictions, living and then dying poor in our “safety zones” of low-quality, subsidized economic ghettos. We may have to dump the whole “Saftey Nazi” idea, and cut back sharply our bloated “Public Sector”, especially in light of a possible collapse of NAFTA, and a downturn in global commodity valuations. We may need Schumpeter’s Storm to get this done.