A majority of Europeans fear the EU could break up in the next 10 to 20 years. This is despite support for EU membership increasing in recent years. So why is there concern the world’s most successful regional block could split apart?

Brexit was a real shock for the European establishment, the seemingly unthinkable happened. For the first time, a country voluntarily left on a wave of Euroscepticism. Yet, far from being a tipping point, the costs and failures of Brexit, have actually increased support for EU membership. Brexiteers hoped the UK example would encourage other countries to follow. But EU Commissioner Josep Borrell said, Brexit – feared to be an epidemic, has proved to be more of a vaccine. There has been a rise in support for anti-establishment parties in the European Union, but so far populists have refrained from talking of leaving the EU because, at the moment, it is not very popular. Nevertheless, there are six pressure points which could cause the EU to breakup.

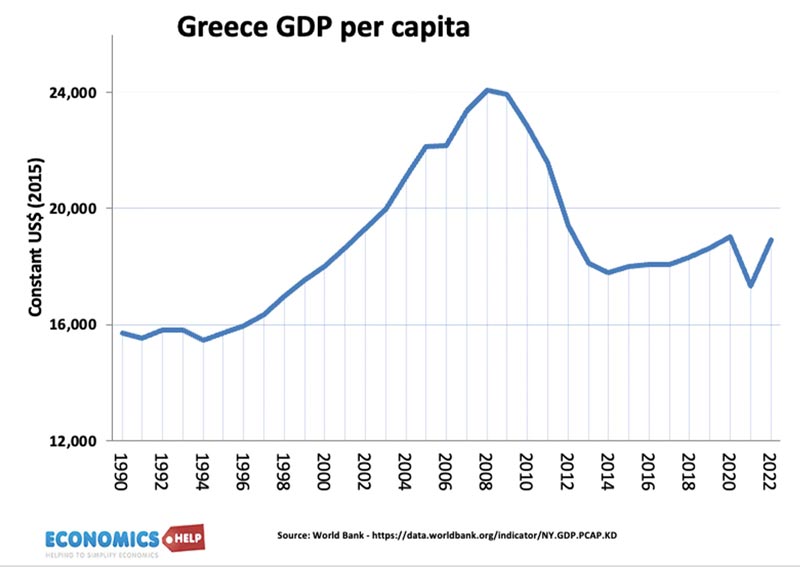

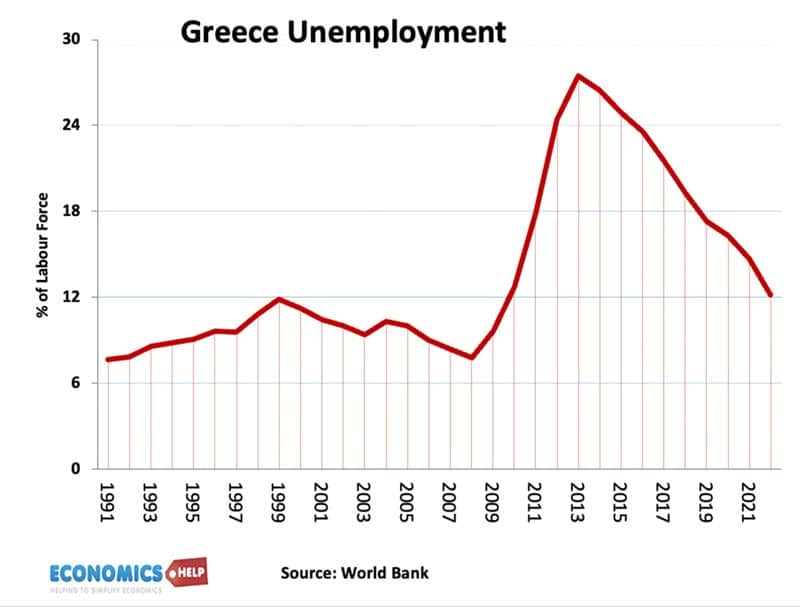

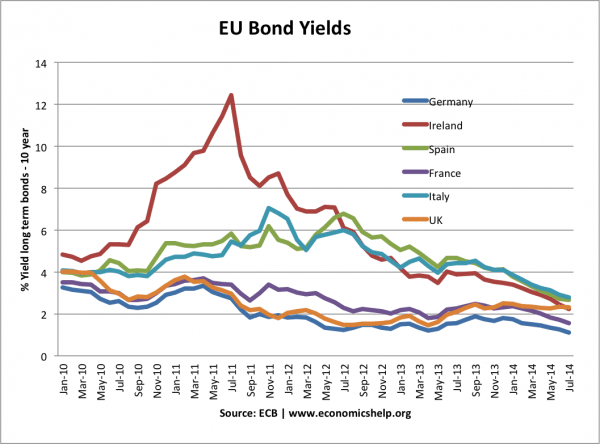

Firstly, the Euro was conceived as a project to foster economic integration, but a lack of flexibility and structural problems have often worsened regional differences. In the straightjacket of the Euro, the Greek economy was squeezed with high interest rates, an overvalued exchange rate, falling demand and a surge in bond yields. The recipe from the EU was austerity – cutting spending. This was the last thing the recession hit the Greek economy needed, but this was the cost of being in the Euro. Rather like the medieval practice of bleeding ill patients, austerity caused a record rise in unemployment and a fall in output.

Yet, despite the obvious unsuitability of the Euro for the Greek economy, even at the darkest moment of the crisis, the most ardent critics of the European project baulked at the idea of leaving the Euro. Because no one would want a new Greek currency. Once you’re in the Euro, even if you don’t like it, it’s very costly, if not impossible for a small country to leave. This is a metaphor for the European Union, once embedded in its systems and economic integration it is hard to leave.

Since the worst of the Euro debt crisis, the ECB did learn some lessons becoming more willing to intervene in bond markets. On the one hand, a deeper crisis was averted but on the other hand, the economic damage Greece experienced and continues to suffer has led to the highest levels of dissatisfaction with how democracy works in the EU. This is the concern that a slowing European economy and economic insecurity will feed political movements less supportive of European integration.

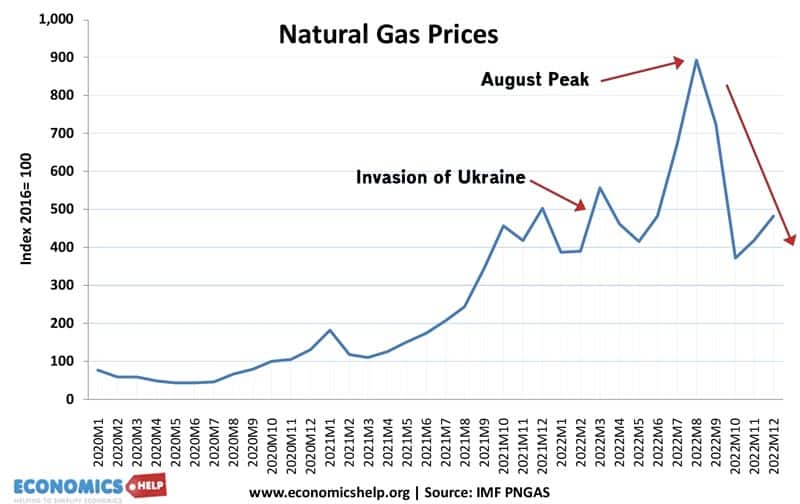

In 2022, the Russian invasion of Ukraine sent gas and oil prices soaring – stressing the European economy. To some extent, it galvanised European unity on foreign policy. But, the loss of gas supplies, also led to cracks in European economic unity. Germany, the economy most dependent on cheap Russian gas, rejected EU fiscal rules and calls for an EU Wide price cap, choosing instead a domestic €200bn package of domestic heating subsidies.

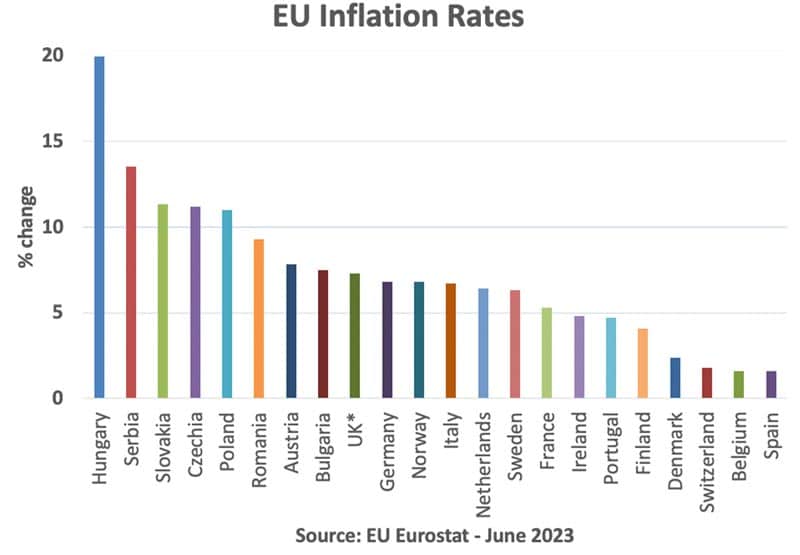

Whilst Germany has the scope to borrow heavily at low interest rates, weaker economies have seen their borrowing costs rise. The energy shock led to high inflation, especially in central and eastern European economies, threatening to cause a divergence of economic fortunes. A divergence of inflation and growth is particularly problematic in the Eurozone because of the common monetary policy – and as Greece and other found out, one size may not fit all. The toxic combination of lower growth, inflation and a cost of living crisis have all lead to support for anti-establishment parties.

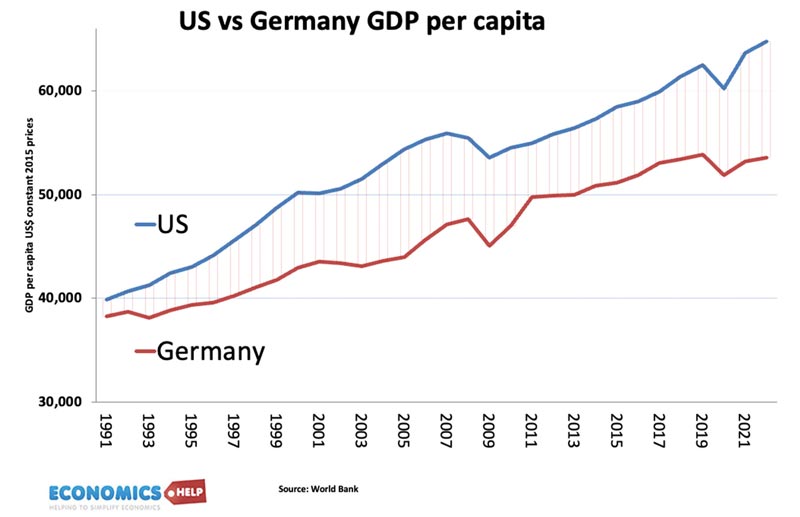

Another challenge to the EU project may come from economic weakness amongst the major economies Italy, Germany and France. A key pillar of the European Union was the marriage between French political leadership and Germany’s economic strength. But, in recent years, the German economy has faltered. Its manufacturing sector has been hit particularly hard by the loss of cheap gas. It has caused record inflation, recession and an unusual economic pessimism. Germany is the biggest net contributor to the EU and its economy is the engine of European growth. The problem is that its past economic success has hidden longer-term problems. It has an ageing population, a dependence on exports to China and businesses complain about a raft of regulations and restrictions which hold back investment. Although fears of Germany’s economic demise can be overblown, European economies are definitely losing ground to the US and rising global stars like India.

Perhaps the greatest threat to a common European response is the migration crisis, which has seen thousands of displaced people, largely from Africa seek refuge in Europe. Countries in the south, such as Greece and Italy and have been at the forefront of receiving refugees and struggling to keep up with the number. The EU has a common external border. It is essential for the founding principle of free movement of labour. But, within the EU, there are widely different views on how to deal with migration. Some countries like Spain have a greater tradition for accepting migration, whilst there has been a backlash from many countries such as Italy at the scale of the problem. It is proving very difficult to create a common migration policy.

In the next few years, the EU is committed to growing in size, but with more members it is to retain unity. An important principle of the EU is a national veto on key policies. It is a way for countries to retain sovereignty whilst working together. But, if the size of the EU rises above 30, there will be increased difficulty in agreeing unilateral decisions. Some argue the EU will need to move to qualified majority voting, but this risks alienating countries who would lose their veto.

An interesting development is the European Political Community established in 2022, including 47 European countries including the UK and Turkey it offers a forum to find cooperation on politics, security, energy, infrastructure, investment, and migration. Could this be the future alternative? A looser confederation of European states, which can pick and choose which subjects to work on.

Europe faces many threats, not least economic slowdown, structural weaknesses in the Euro and a migration crisis that raises strong political pressures. Yet for all the crisis facing the EU, there is at the moment, little appetite to undo the decades of economic and political integration. Once embedded, it is hard to undo, it is ironic that Brexit could end up being a real shot in the arm for the European Union. Yet, nevertheless, in a fast-changing world, nothing can be taken for granted. Within a couple of years, the whole economic and political certainties of the post-war period have been threatened, and increasingly there is a risk of regional blocks within the EU developing. In particular elections in Poland will be watched closely, there is a chance elections will be dominated by the far right, creating an illiberal, authoritarian government which is close to Hungary, but increasingly distant from the pro-EU centre.

On the issue of Brexit, European unity held pretty well. The big threats facing the European economy such as global warming and the growth of big tech and multinational tax avoidance, do require cooperation, so there is definitely a logic to a co-ordinated European movement, but continued economic and geo-political shocks could undermine the foundations of the EU. Whether Brexit is a one-off or a sign of things to come is at the moment uncertain.