There have been a couple of thoughtful pieces from Paul Krugman challenging the consensus that Brexit will have very high short-term economic cost.

Krugman’s argument is:

- There is uncertainty, but uncertainty on itself is not enough to create a significant demand side shock.

- In fact, when the uncertainty is resolved, we could have a mini-boom as delayed investment decisions are then taken six months later.

- The turmoil in the markets is actually quite mild by comparison to other events. The dollar denominated FT-SE 100 hasn’t fallen much and has regained most of initial falls. The Pound has fallen, but not at an unprecedented rate to create instability, and of course a falling Pound will help boost exports and aggregate demand.

The most interesting part of the point is the link between politics, emotion and economics. The vast majority of economists were united in saying Brexit would lead to economic costs (decline in trade, uncertainty, decline in inward investment). But, in the EU campaign several senior politicians told voters to ignore the advice of ‘experts’ like economists – because ‘economists’ are always wrong.

So it is understandable the human nature in economists would like to be ‘proved correct’ and for people to see the economiccosts of Brexit. But, with this mindset (especially with raw emotion of losing referendum and political turmoil) this can cloud your judgement and you start cherry picking looking for evidence of depressed investment and perhaps exaggerating the short-term costs.

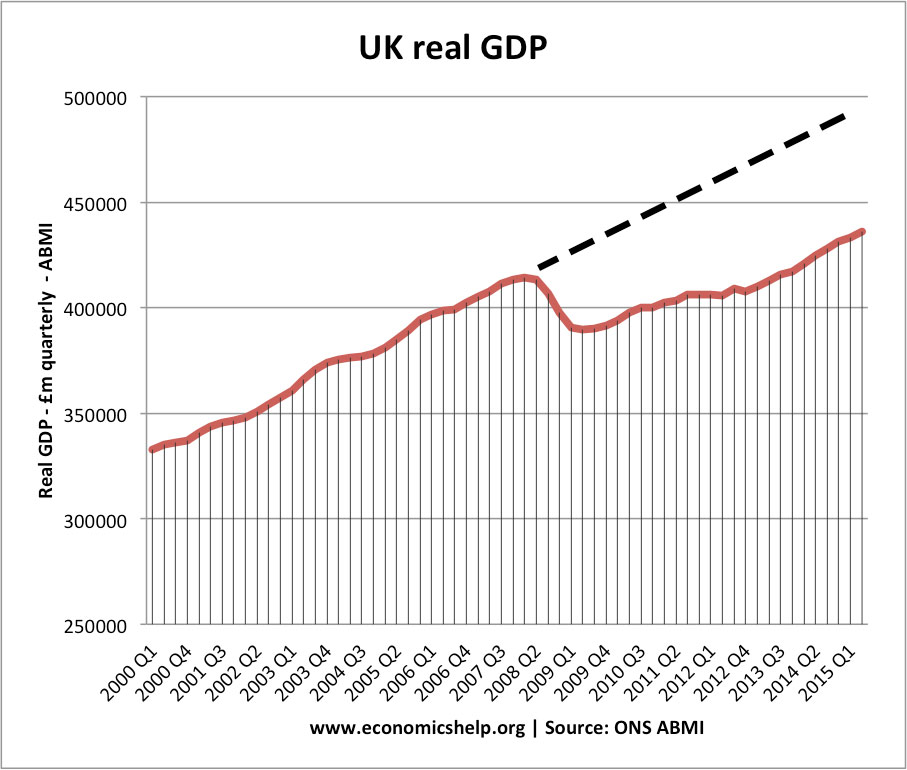

Note: Krugman does not defend Brexit, and argues there will be a long-term cost to Brexit. (Macroeconomics of Brexit) On long-term costs, Krugman admits it is very hard to calculate, but as a best guess suggests – a permanent loss of 2-3% of real GDP

“This reduction in trade relative to what would otherwise happen will, in turn, make the British economy less productive and poorer than it would otherwise have been. It takes fairly heroic assumptions to make this into a specific number, but 2-3 percent lower income in perpetuity seems plausible.” – Paul Krugman.

- Note, you can lose 2-3% of real GDP in perpetuity, without even having a recession. In theory, a decline in ease of trade, less attractive for inward investment could just reduce the UK’s long run trend rate from say 2.5% to 2.3% for a few years. It is possible the economic costs of Brexit will not be felt in easily understandable terms – i.e. a recession.

Short term Macro economic costs

But, is Krugman’s macro-economic reasoning correct? You could point to other factors, which may well cause a more significant demand side shock.

More than uncertainty. Leaving the EU is more than uncertainty; businesses are realising the UK is leaving the EU and in all probability direct access to the Single Market. This makes the UK a permanently less attractive place to set up a HQ and invest for exporting to EU. It is not just a case of delaying until uncertainty is resolved. When the UK / EU deal is finalised, the UK will not be in the EU and the UK may start to lose its global position as top 3 location for inward investment.. Already investment decisions have been delayed – possibly permanently. EDF delays Nuclear Power station. Companies like Vodafone and Easy Jet have hinted at moving their headquarters out of Europe.

- However, one other point. Delays in big investment decisions are quite striking, but Brexit could lead to less well-publicised opportunities, e.g. exporting firms benefiting from weaker Pound.

Decline in consumer confidence. Given the importance of consumer spending to the UK economy, consumer confidence is very important. In March 2015, Market research by GfK state that consumers’ confidence in the UK economy has fallen from + 6 to -12, a swing of 18 points. Consumer confidence is volatile and could swing back, but in this climate, we are likely to see a withdrawal of consumer spending, falling house prices and this will definitely have impact on UK aggregate demand.

Will exports benefit from devaluation? In 2011, the unfortunate aspect of Sterling’s devaluation is that it only had a very limited impact on increasing UK exports and failed to reduce current account deficit. In that period demand for UK exports proved to be very inelastic – harmed by weak Eurozone growth. The problem the UK faces is that its main trading partner – the EU is struggling and a recent recovery could easily be put that into check.

See more: Will Brexit cause recession?

Why Chancellor should go

During the referendum, the chancellor Osbourne made many dire predictions about UK economy post-Brexit. Perhaps the low point of the entire Remain campaign was Osbourne’s threatened ‘punishment budget’ of tax rises and spending cuts. Of course, now we are leaving the EU, he has no intention of implementing this kind of budget because it would definitely cause a recession.

However, it is bad thing to have a Chancellor who has made many dire economic predictions about the economy. A chancellor should , as much as possible, have an optimistic approach to the UK, even if it is making the best of a bad job. There can be room for in the back of your mind wishing to be proved right.

Fortunately, the next chancellor will receive quite a lot of support from the governor of the Bank of England – who has been a rare voice of reason in this Brexit trauma.

“Will exports benefit from devaluation? In 2011, the unfortunate aspect of Sterling’s devaluation is that it only had a very limited impact on increasing UK exports and failed to reduce current account deficit. In that period demand for UK exports proved to be very inelastic – harmed by weak Eurozone growth”

The exchange rate eleaticity of demand for exports might have been quite high. We should not confuse the effects of other factors, such as weak Eurozone growth, with the effects of £depreciation, especially if consisdering future efefcts. We have to try to compare outcomes with what we think would have happened without £depreciation.