In 2010, the UK hit at a record peace time deficit. The incoming government sought to reduce debt through austerity.

In 2010, the UK hit at a record peace time deficit. The incoming government sought to reduce debt through austerity.

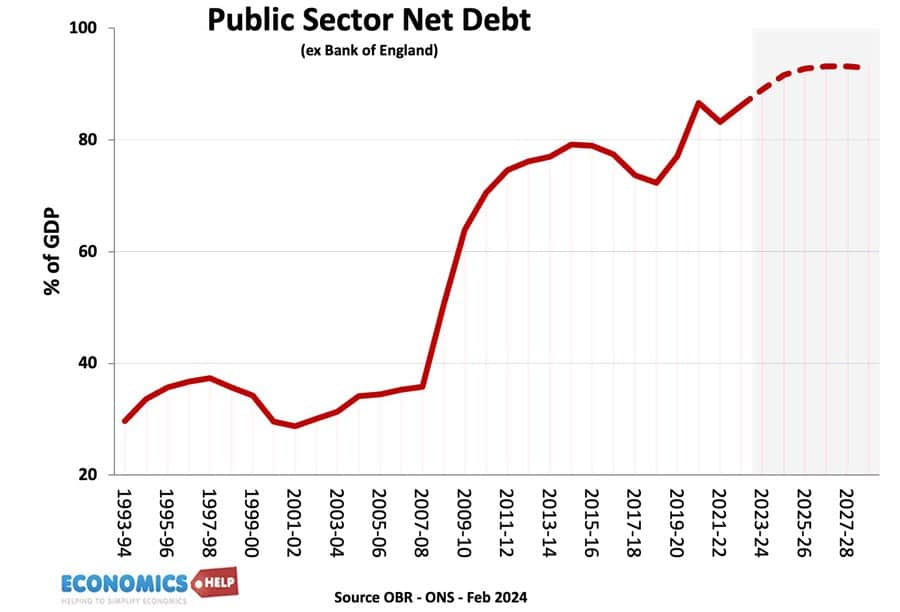

But, over the next 13 years, debt to GDP has steadily increased and is forecast to keep rising, with a vague hope that debt will fall in four years time. Due to deteriorating economic circumstances the Labour Party have cut back their green investment plan, saying we can’t afford it. It’s not just central government debt, local councils are on the brink of bankruptcy, the High Street is in crisis and mortgage insolvencies are rising. But, is it as bad as these negative headlines, and is there a way to break the doom loop of rising debt and falling growth?

Problems with UK Fiscal Situation

Unfortunately, the UK fiscal situation is worse than it appears for three reasons. Firstly, The forecasts are based on unrealistic assumptions of government spending. The head of OBR was scathing – stating there debt forecasts had to use government figures, which had been plucked out of thin air. “Worse than fiction” does not offer reassurance. There are no spending plans by department only two numbers on tax and spending. It means that whoever is the next government will need to implement swinging spending cuts to meet these arbitarry target. To achieve these cuts will require deeper austerity than 2010.

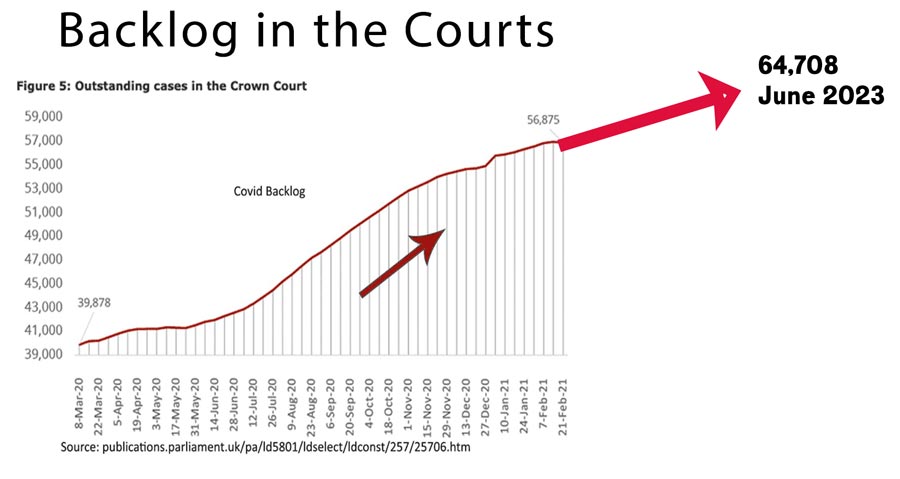

The problem is that there is little left to trim. Education has been hard hit, leading to crumbling schools, low teacher morale and slipping standards. The legal system has been underfunded, leading to a backlog of cases and waiting list.

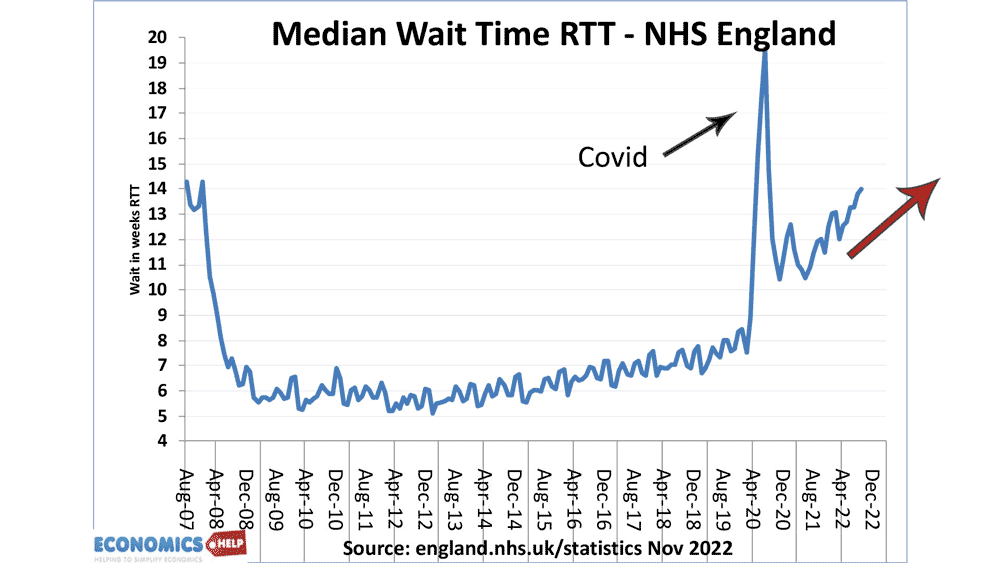

Even the NHS which has seen increases in real spending is struggling to keep up with demand as an ageing population and sicker population places greater strain on services. One reason for the UK’s poor economic growth is a record numbers of sick people, unable to work. Recently ONS revised the UK’s long term sick to 2.8 million. Underprovision of health, has a large economic cost.

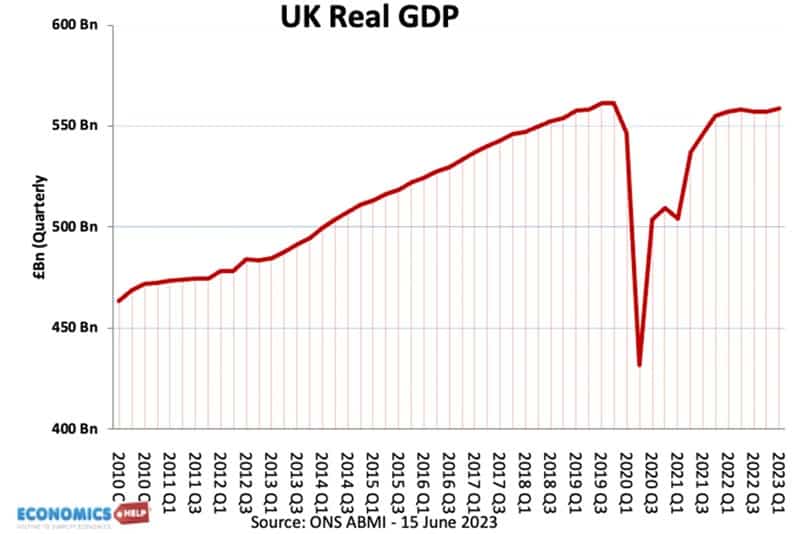

The second reason to be concerned about the UK’s debt is that in the past 15 years, economic growth has dramtically slowed down. This means we have seen lower tax revenues than expected. But, at the same time, there is growing demand for government spending from pensions, health care and economic inactivity. If we ignore population growth, real GDP per capita is basically stagnating.

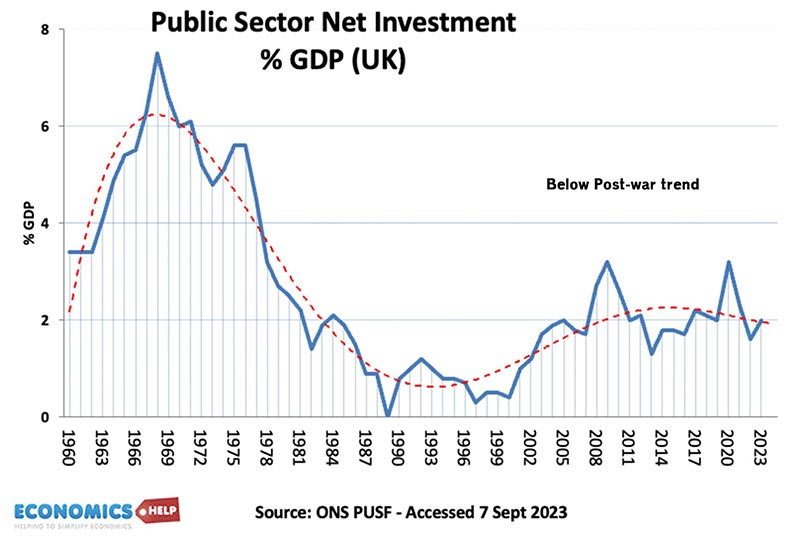

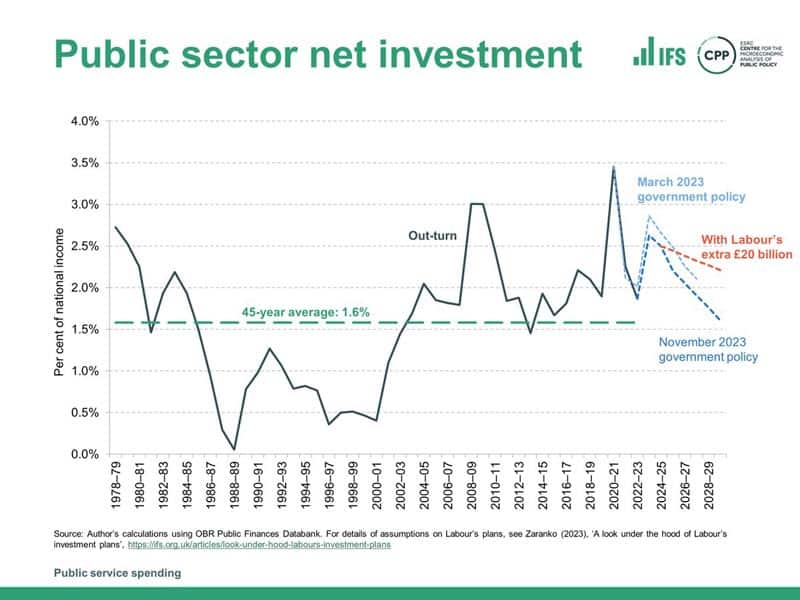

Given the pressures on government spending, the easiest thing to cut is public investment, and it is much lower than the post-war period. Under Conservative plans, it will fall to 1.5% of GDP. Under Labour’s new plans it will fall to an estimated 1.6% little different to the government’s own fiscal position.

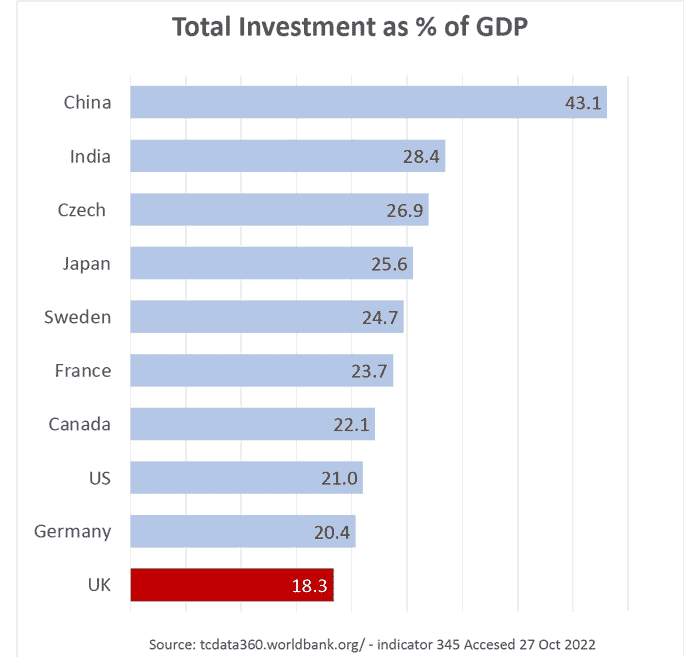

The problem is the UK has had a prolonged period of low investment. Private sector investment has fallen behind since 2016 and the UK has one of the lowest rates of investment in the OECD.

This combination of low private and public sector investment is a key factor behind the UK’s very low rates of growth. It also stores up problems for the long-term. Potholes, congestion, lack of housing and poor health all damage the long-run potential of the economy.

Now, in fairness it has been a difficult global environment, higher energy prices, slower productivity growth, Europe and China struggling, but it would be a mistake to argue there is no alternative. The US economy although – far from perfect shows that higher growth is possible. Since 2018, the US has clearly outpeformed the UK and European economies. Whilst Germany and the UK pursues austerity, the US took something of a gamble with a bold industrial policy, incentivising investment in green technology. It led to a surge in private sector manufacturing investment. It has been expensive and has led to significant US budget deficit, but is also leading to higher tax revenues. And this is the real reason behind the UK’s long-tern rising debt. 15 years of below trend economic rate has caused tax revenues to fall behind the demand for services. With low confidence and investment, the economy has become stagnant.

Also, whilst, we think we can’t afford investment in renewable energy, it is worth bearing in mind, the cost of the receent energy price surge was very expensive. £280bn. This manifested in inflation and a cost of living crisis. This is why investment in insulation and renewable energy can have significant long-term benefits. There is a cost of investment, but also cost of non-action.

The government’s fiscal rule is to reduce debt over the long-term, but the problem is economists have very little faith in these fiscal rules. It encourages creative accounting, and in the UK seems to cause cutting public sector investment, something the UK needs more not less. This is the real reason for the UK’s deteriorating debt situation, – a lack of economic growth.

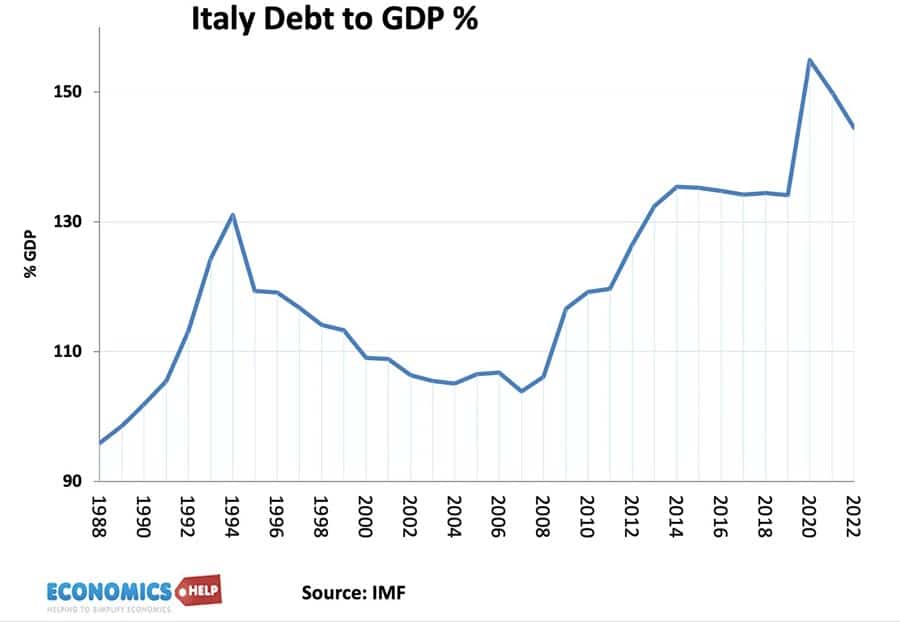

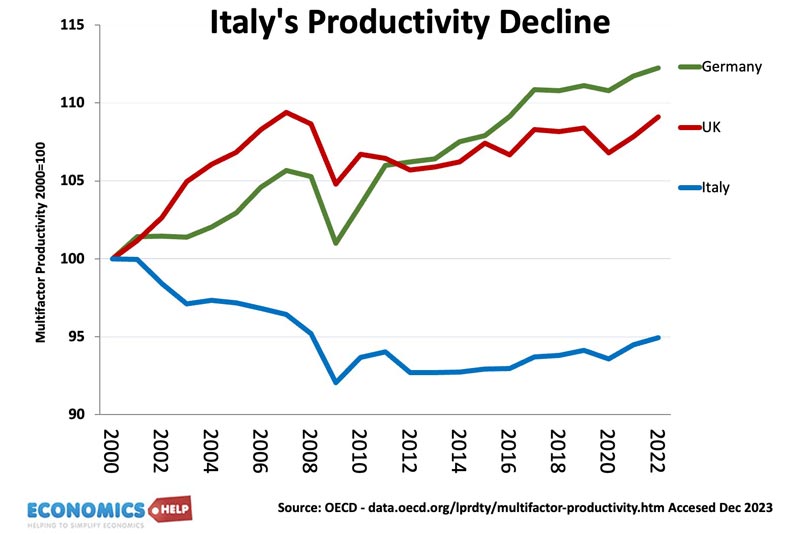

There is a real risk, the UK could start to emulate Italy. Italy has stopped growing since 2000, and despite frequent efforts to reduce their budget deficit, debt to GDP in Italy continues to grow.

This is the worst of both worlds, low growth and rising debt. The best policy for a new government would be to prioritising kick starting economic growth. Ironically, Truss and Kwarteng had the right idea to increase growth, they just went about it in the wrong way.

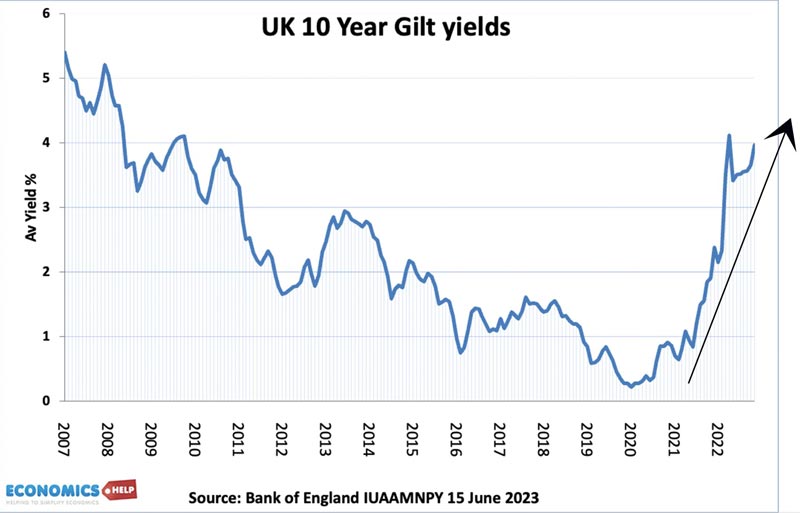

A third problem about the UK’s fiscal situation is rising interest rates. Since the return of inflation, bond yields have soared, massively increasing the cost of debt interest payments. When borrowing was cheap, the UK didn’t take advantage to invest, it was a missed opportunity, but that era is probably over.

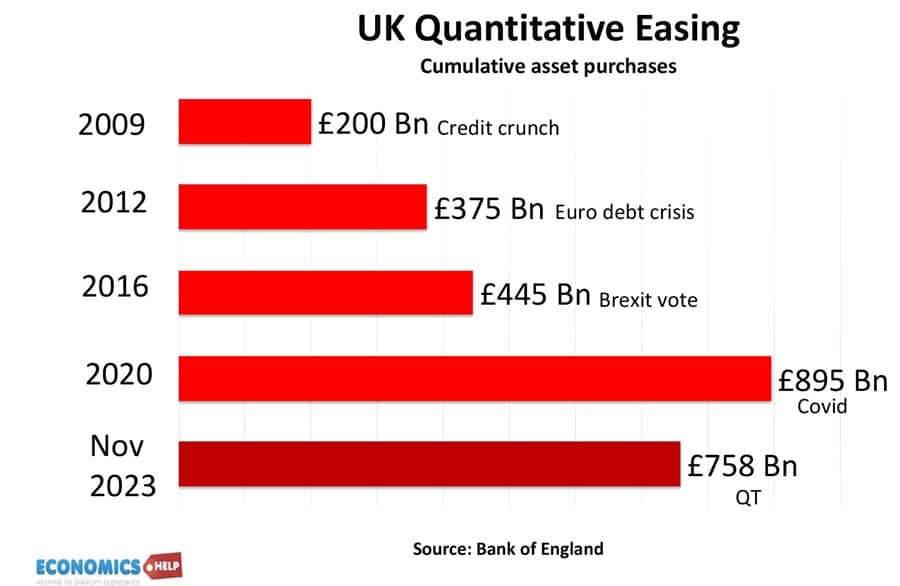

The future direction of interest rates is uncertain. Inflation is forecast to fall, but under QE the Bank of England bought £895bn of bonds – which made government borrowing cheaper. But now it is trying to reverse all this and sell the bonds they own. It has actually sold £140bn, but it still has another £750bn to go. Quantitative tightening will push up interest rates further and make it harder for the government to borrow. No one really knows the impact of unwinding £700bn of QE or whether Bank will even be able to achieve it. But it definitely makes a future government’s role harder.

Does the rise in interest rates and market reaction to the mini-budget of 2022 mean we should just give up on public investment, and focus only debt reduction? I think that would be a mistake for three reasons.

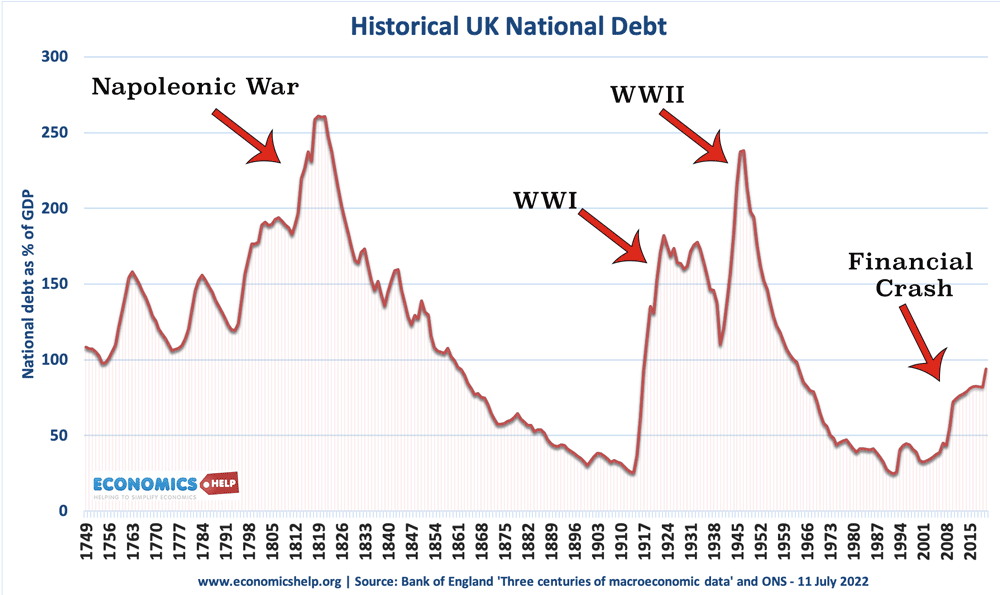

Firstly, the UK debt situation is deteriorating, but it was much worse for most of the post-war period. In 1950, the UK debt was over 200% of GDP. But, we still invested in NHS, education and building houses. The reason debt was not a problem was – partly we had a big loan from the US, but mainly, in the post-war period, economic growth averaged 2.5%. This is the real method to reduce debt to GDP. Not austerity, which reduces demand and investment, but consistent economic growth. Now, economic growth can come from many sources, it could be private investment, new technology, it doesn’t have to be a government green energy deal. But, at the moment, hoping something will turn up to change the UK’s fortunes feels a bit too much like wishful thinking. Bold government investment can stimulate private entreprise. At the moment, the private sector is lacking in confidence because of frequent u-turns in policies, costly changes to trade rules and weak growth.

Arbitarty debt rules are not helping. They are too easy to fudge and, but also they fail to distinguish between borrowing which can help long-term economic growth. This doesn’t mean the UK can improve its public services by borrowing. If we want to tackle long list of waiting lists and have higher spending, we will need higher taxes. If we want lower taxes, we can go private or put up with the long waiting lists. However, if the economy is stuck in the doldrums, then there is strong logic for some fiscal intervention to kick start the economy. The goal would be to achieve something called ‘escape velocity’ This means escape the cycle of high debt, low growth, low investment. When the economy escapes this doom loop cycle of low growth and austerity, then the government starts to have a much better trade off and can concentrate more on reducing debt. I googled escape velocity and realised I wrote about this in 2013, ten years ago. Ten years later we still haven’t achieved it.

To reach escape velocity – you do need some degree of boldness and not to be hemmed in by artifical debt targets. Things might seem grim, but it could change for the better.

Related