In 1978, the Conservative Party hit on a fantastic election poster, Labour’s not working. Unemployment had recently hit 1.6 million or 5%. Ironically, a few years later unemployment would soon double to over 12% after the devastating early 1980s recession.

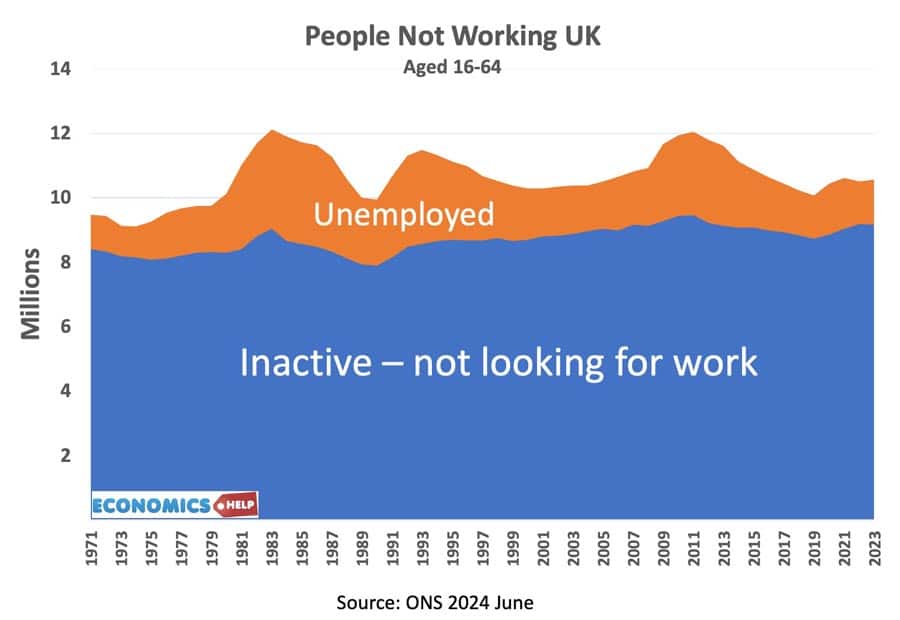

But, what about 2024, is there a new epidemic of economic inactivity, people not working? Well in total, there are 10.5 million adults not working for various reasons. This contrasts with 32 million adults in employment – so nearly one-quarter of the adult workforce. Why are so many people not working and does this explain the reason for high immigration? And can we do anything about it?

Inactivity

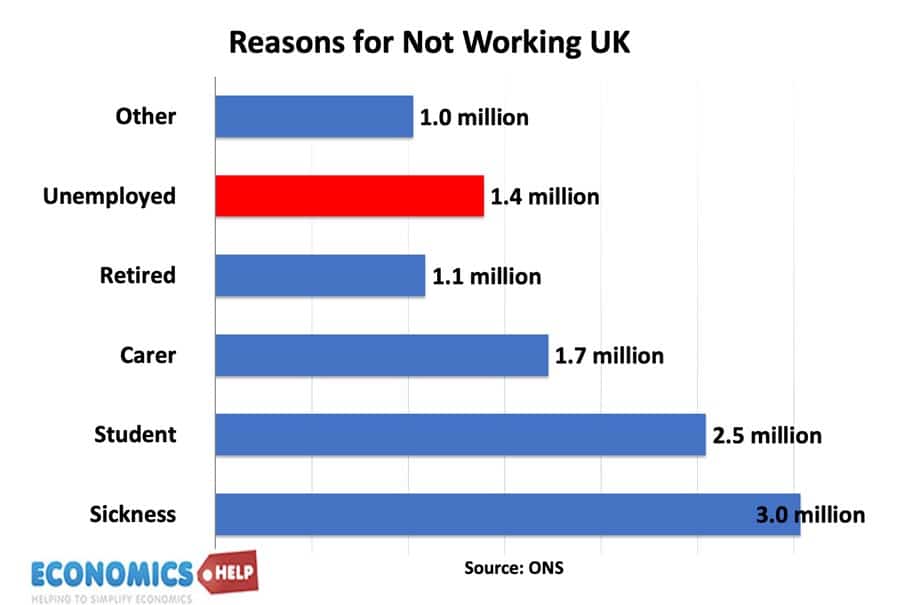

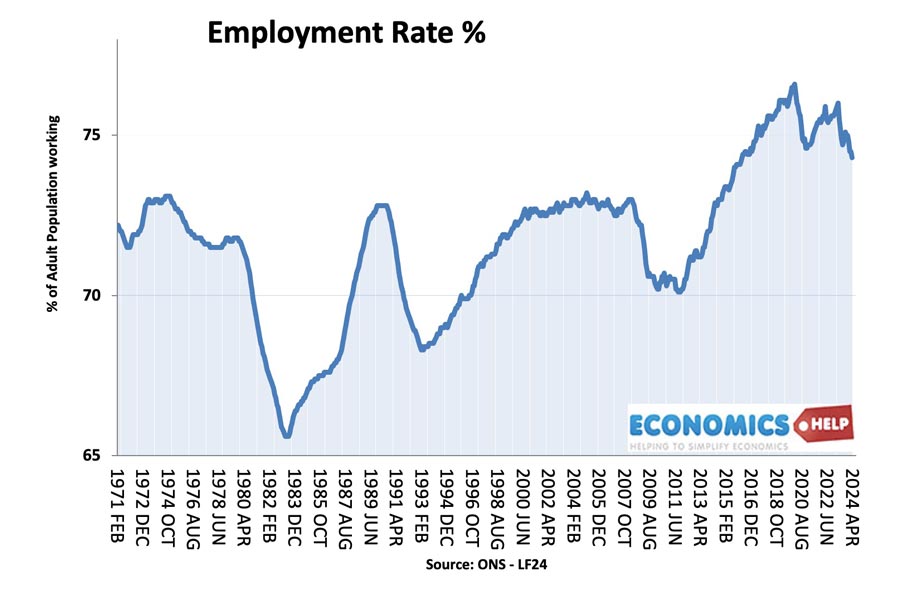

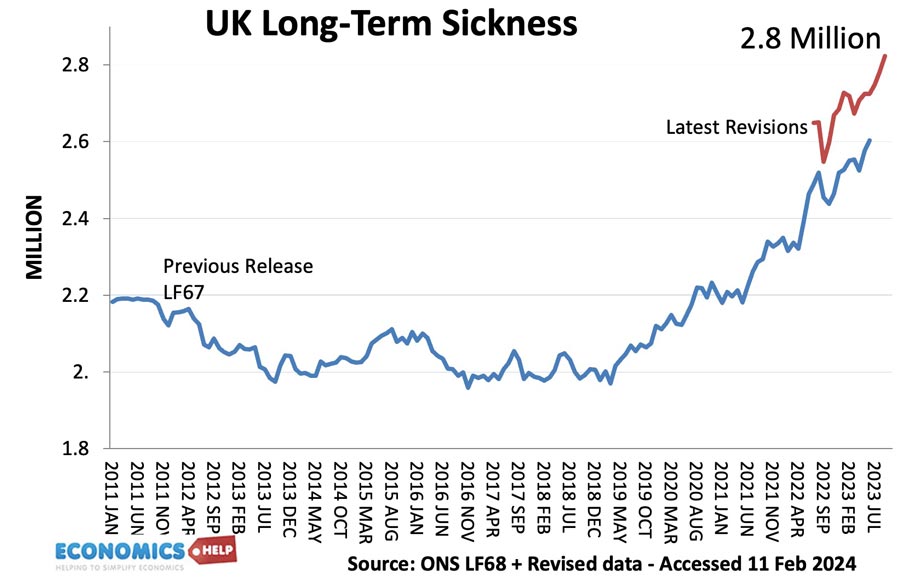

Firstly, this rate of people not working is nothing new. Since the early 1980s, we have consistently had over 10 million adults not working. The peaks in early 80s and 90s correspond to recessions and higher uenmployment. This figures of 11 million includes both those who are counted as unemployed and also those who are counted as economically inactive. Inactive means not actively seeking work. So why are there nearly 9 million inactive adults? The biggest group is people leaving the labour force because of sickness. 2.8 million long term sick, 200,000 temporary sickness. This is perhaps the most concerning sector, because it has increased by nearly a million in the past few years.

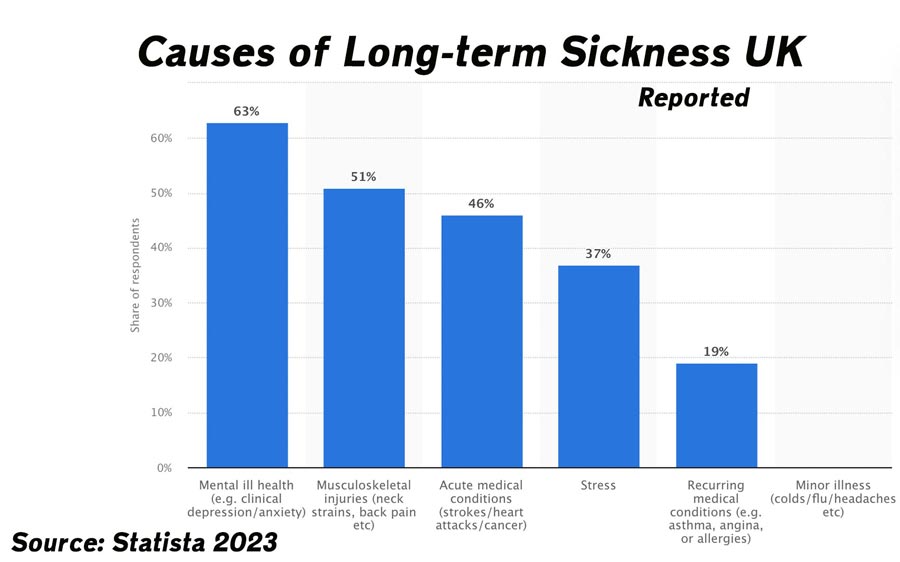

The biggest cause is mental health issues, followed by bad backs and acute medical conditions. Neurological conditions like strokes, parkinsons, dementias have all increased rapidly in the developed world. But, it is not just the long-term sick affected, another leading cause of inactivity is those who stay off work to look after family members with health conditions 1.7 million. In the 1990s, this reason was nearly double at 3 million. Possibly more feel obliged to work as well as look after family members. Certainly, the care sector is particularly hard hit with local councils overwhelmed by demand. But, without government support, many are left juggling both work and caring. The next reason for inactivity is students. But if you are juggling several things at once you might be interested in today’s very quick video sponsor.

Students

The number of students in the UK has increased from 1.5 million to 2.5 million, largely due to the expansion of university education. It is a far cry from the 1960s, when just 200,000 were at university. On the one hand, the UK’s service sector economy has a need for skilled and qualified workers. More in education means fewer workers, but also a more qualified workforce. The UK desperately needs to increase labour productivity and higher education is one route to this. Still some might argue, we pushed university education too far, with less academic students gaining little value from 3 year academic degrees, when shorter vocational training may have given greater benefit.

Early Retirement

The next big reason is early retirement. In 2009, this reached 1.5 million but has since fallen to 1 million. A reflection perhaps of a decade of ultra low interest rates and stagnant wages forcing more people to go back to work rather than take early retirement. On the other hand, rising house prices have given homeowners who have paid off their mortgages more wealth to be able to afford early retirement. The last reason for inactivity is “other”. The ONS says this includes people waiting to decide what to do next, and people who don’t need to work. Perhaps people who won the lottery or more likely inherited money or grow their own food. The last group of people not working are those who are officially counted as unemployed. People actively seeking work. A good question to ask is how come there are 1.4 million unemployed when firms complain about shortages and the need to hire immigrants from abroad. Firstly, in any economy you always have some frictional unemployment, this is people taking time to move between jobs. If you lost your job tomorrow, would you immediately take the first cleaning job that came along? Probably not, you would prefer to give it a few months to see if you can get a job suited to qualifications. Secondly, there is a mismatch in labour skills. There is a shortage of say carers and medical staff. Not enough people want to follow these careers. This is a combination of economic factors and also cultural factors, e.g. picking fruit is not seen as a career but is more suited to seasonal migrant workers. Certainly, firms do complain that native-born workers just don’t want to do certain types of jobs.

Benefit Levels?

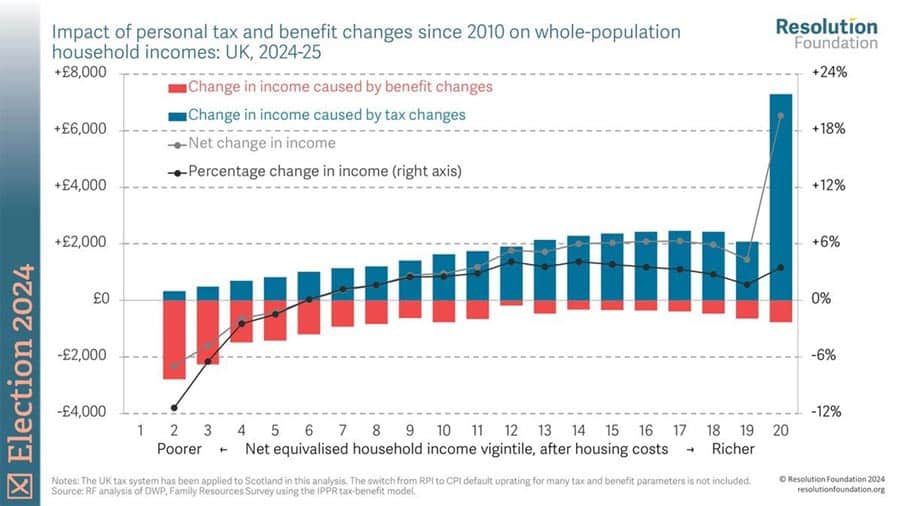

Do we have high levels of economic inactivity because of generous benefits? In the past 14 years, the poorest decile have seen a fall in real incomes because of falling real value of benefits. Unemployment benefits have become a smaller share of median wages. Sickness benefits are not particularly desirable. Also, falling housing benefit has pushed more into poverty, particularly affecing families with more than 2 children.

Can anything be done to reduce levels of inactivity?

Firstly, the rate of employment is actually near an all time high. More people are in employment than ever before. Secondly economic inactivity is not necessarily a bad thing. Education has value, so does being a carer, in a way, this is very valuable work, just not paid. Just because you don’t have a formal job doesn’t make it any less worthwhile. Nevertheless, the social care sector does need greater attention. Many people who have to stay at home as carers would like to work, if circumstances were different. Unfortunately since Theresa May’s so called death tax suggestion during 2017 election, parties don’t want to touch it.

Long-term Sickness

A big concern is the rise in long-term sickness. Certainly, record waiting lists of over 7 million cannot be helping. Certain departments like mental health are particularly stretched, despite this kind of anxiety be given as a reason for not being able to work. I’ve spoken to quite a few employers who really struggle to get staff, and they report a cultural shift in the past few years with workers becoming much more flakey – willing to take days off or less willing to look for work. The whole Covid experience did change perceptions of work, there was a greater willingness for people to question the whole work experience. It is still debatable how real this kind of cultural shift is, but it is hard for policy to make a quick difference.

Disappointed you don’t have Degrowth or Doughnut Economics on your website Tevjan. 😔

Best resources for these are Kate Raworth & Jason Hickel.

The 25% real unemployment figure is why 100s of people apply for one basic software QA tester role on a starting salary of 24K in 2025 ! Companies are tightening their belts and there simply are not enough jobs in the British economy since de-industrialisation and the rise of AI and automation and the lack of any UBI.