People often observe my videos/articles on the UK economy tend to be doom and gloom, this is partly the youtube alogorithm, but mainly because the UK economy really hasn’t been doing very well, whether you look at average wages, productivity or housing costs, it’s pretty grim and you can’t change these facts. And there is a reasonable case that it will continue to deteriorate. But, for a challenge, I’d like to look at a more optimistic take on UK economy and what a strong recovery could look like and what could cause it.

First of all good news that can slip under the radar.

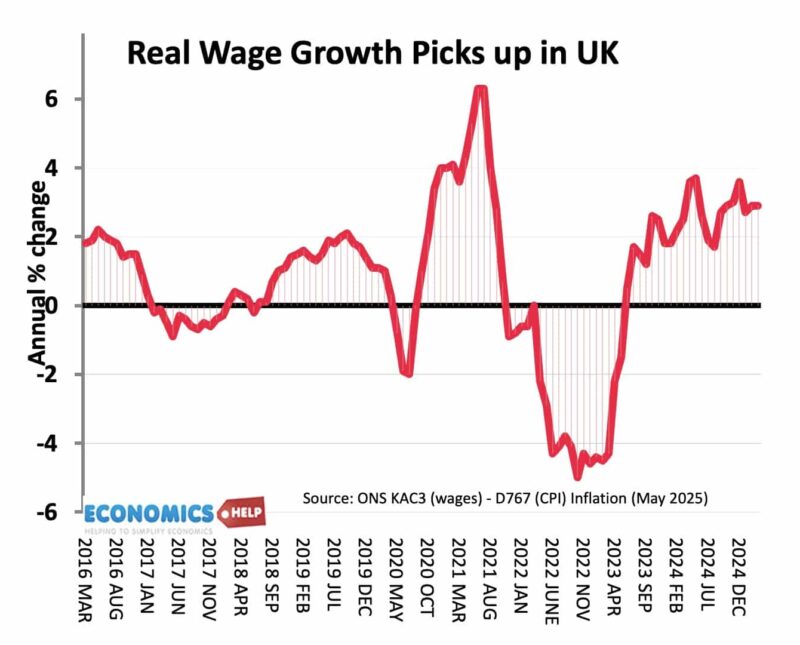

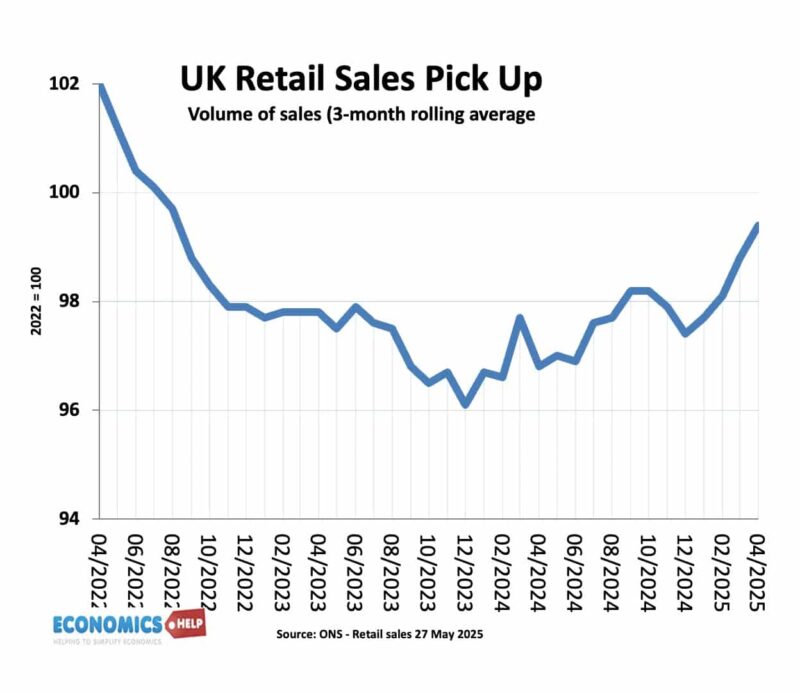

Since April 2023, real wage growth has averaged 2%. And this growth in wages has supported a recovery in retail sales.

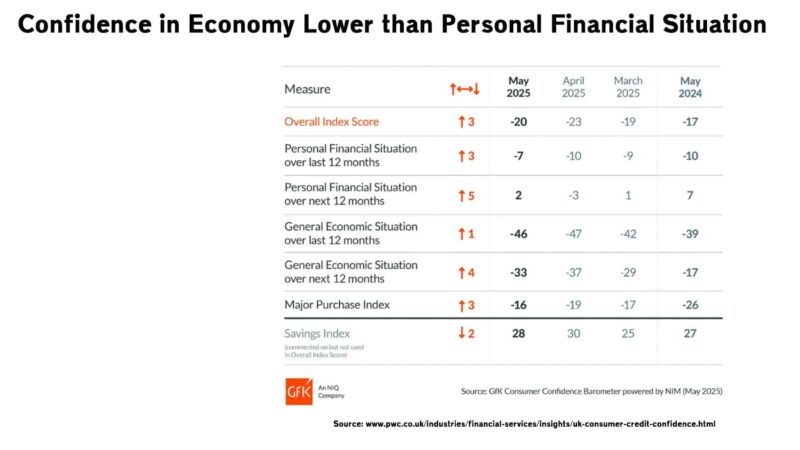

In the past few decades, the UK economy has often relied on the service sector and consumer spending to boost growth rates. As a result of rising real wages, confidence levels have improved from -23 to -20. Fantastic talk about clutching at straws.

But a really interesting divide is that on the general economy there is a net score of -46 – a near record low. But, in terms of personal financial situation, there is a positive score of +5, a big improvement over April. The strength of personal financial situation is reflected in growing savings. Since the pandemic, households have a significantly increased level of savings; in fact, it is very unlike the UK economy to have such a high savings rate if 12%.

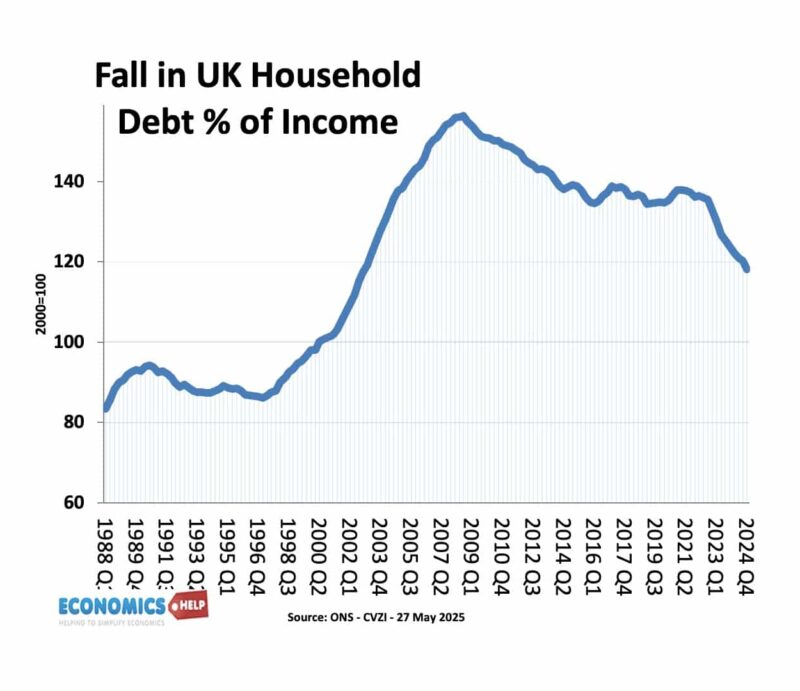

We have also seen a decline in household debt-to-income ratios to the lowest levels since 2004. It is worth bearing in mind, this is for the average household and it can mask problems at the lowest end of the income spectrum, with squeezed benefits particularly affecting working-age people out of work. But, this rise in savings reflects the dichotomy between personal finances and a general view of the economy. If, and I admit this is a big if, people became more optimistic about the wider economy, it could lead to improvements in spending and investment, which could break some of the recent stagnation. Other more positive aspects of the UK economy include one of the lowest unemployment rates in past three decades, though we shouldn’t forget there is a rise in people not working just on sickness benefits.

Inflation

Last month’s inflation was a big jump to 3.5%. CPIH is even higher. A large part of the jump was the rise in energy bills and water bills. But lower gas prices mean that from July, energy bills will fall by 7%. This will definitely help reduce inflation later in year. But, worryingly, consumers are not convinced, inflation expectations are actually going up, this is because of a sense that bills rising faster than inflation and perhaps fears of tariff-related price increases. But this really highlights how dependent the UK economy is on gas prices, and since 2022, there has been increased volatility of inflation and energy prices. I feel this leads to loss of confidence and need for higher savings. Who will trust energy prices to remain low, when prices keep going up and down like a yo-yo. Fixing the energy market is a big issue for households and industry.

Will growth be maintained?

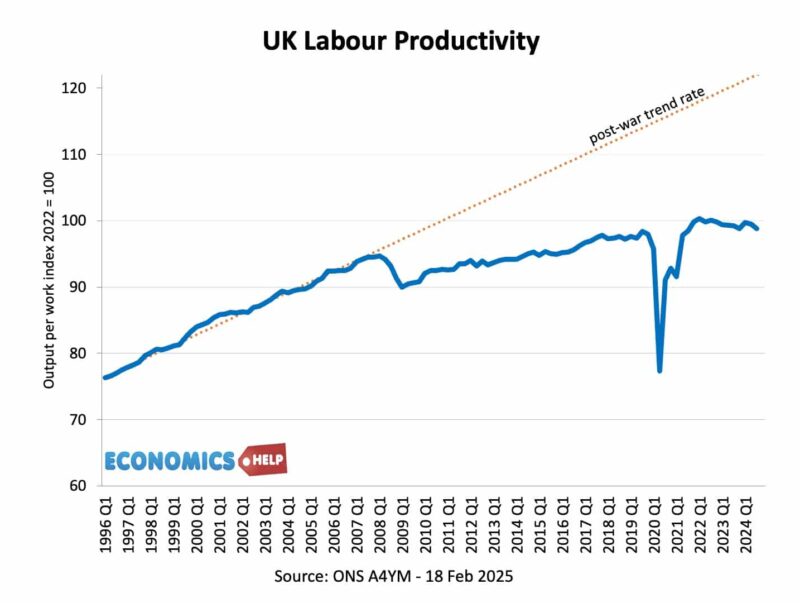

But, a good question is how durable is this growth in real wages? Part of the increase is simply undoing the big fall in 2022, when inflation ran at 10%. Workers are catching up for lost wages, and also big rise in public sector wages after a decade of austerity. If the UK is to maintain real wage growth of 2% for a considerable time, something would need to change with productivity. Productivity is output per per worker. And if this is stagnant, firms can’t pay higher real wages.

The OBR have spent the past 13 years predicting an uptick in productivity that hasn’t materialised, so it would take a brave economist to stick your neck out and forecast it is finally going to come at the 14th time of asking. But, it is still worth considering. There are 3 aspects to the UK productivity stagnation. Firstly, there has been a global slowdown in productivity growth since 2008, secondly, the UK has done relatively worse, and thirdly productivity has been terrible since 2020. To some extent the economy is dependent on global trends in productivity and technology. But, some things are improving. AI could transform the economy, a year ago I was a sceptic, but now I see how it can help. Many technological advances are occuring. In California batteries supply 30% of electricity at peak demand. Battery technology will improve and be a big help in the future.

Migration and productivity

Also, one theory for very low productivity growth since 2020 is the very high levels of migration of people who tend to have lower average wages. If you get over 2 million people with slightly lower wages and skills, like a simple batting average, this will depress labour productivity. The Migration Advisory Committee (MAC), suggest that free movement of labour and high migration may have incentivised recruitment over labour saving capital investment. Since 2010, you can see that economic growth has primarily come from higher levels of employment, but little from capital and multi-factor productivity. The big Boris boom in migration is starting to fade. Last year migration fell to 450,000 still very high, but it will probably fall, this could have some impact in increasing productivity, though it could also lead to a shortage of care workers and fruit pickers. Also, if you really like to see your glass half full, you could even argue that the increase in the minimum wage and higher NI tax will be another factor incentivising capital investment and higher labour productivity. Another perspective of course is that it will lead to fall in employment. Recent PMI studies show slight decline in orders in April.

What is UK economy good at?

Another question what is the UK economy good at? If you wanted to be cynical you could say Last year we had a 23% rise in the number of buy to let companies setting up as landlords try to avoid tax and charge more rent. 20 years ago Patrick Collinson wrote how if the US domainates technology and Germany car production, the UK produces buy-to-let landlords. But, although this is true to some extent, the UK does have some world-class industries in bio-tech research, nuclear components, media and film, IT and computer gaming development, even the premier league contributed £8bn to UK economy and that was in covid year of 2021/22

Funny story, at Christmas I got some book tokens and I bought a book “Made in Britain” by Evan Davis– why our economy is more successful than you think. I thought it would give ideas, but when I read it, nothing was really resonated. I looked at the date of the book, published 2011, It hasn’t aged particularly well in the past 14 years. And away from consumer spending and service sector, the industrial side of the UK is in deep recession, despite a small uptick at the start of the year, output is at the same levels as 2016.

Global Headwinds

My efforts to big up the UK economy are now starting to fade. There is some improvement in personal finance, but there is a still a lot of unknowns and global uncertainties to make a very convincing case. Bond yields are rising on the back of uncertainty, rising deficits, and the UK has been more badly affected than most countries. The UK has one of the highest bond yields in G7 and this has played havoc with government’s very small fiscal headroom. There is understandable awareness that the government could snuff out any recovery with more tax rises or benefit cuts. The global economy could also be a real problem with a slowdown in US growth, and tariff wars affecting the UK. The EU reset is a step in the right direction, but it hard to get excited about a deal which might raise GDP by 0.3% over a 15 year period. A more optimistic take would be to see this as a further step in the right direction.

Quick question

Does economic growth actually improve living standards? Without higher real GDP per capita, it is certainly pretty hard to improve living standards. Now in theory, if housing costs fell drastically or new technology massively reduced energy bills, then you could see improved living standards without any increase in real GDP. But, also it is a fair point, that sometimes, even if you have economic growth and real GDP per capita growth, it fails to improve living standards, especially, if economic growth pushes up rents and house prices, meaning that the gains of economic growth are unequally felt. Going back to Collinson’s quote, higher rents do increase GDP, but obviously, the distributional impact is uneven. But, also, higher growth will help improve tax revenues, and enable more spending on benefits and health. Without economic growth, you can expect more austerity. So both are needed at the moment, economic growth and better distribution. Well if this is the positive angle, what does the negative angle look like?