In economics, there is often a trade off between macro economic variables. A simple trade off could be – increase interest rates; this leads to lower inflation, but also lower output. Cut interest rates, and you help boost growth, but increase inflation.

In an ideal world, we would have low inflation, high growth and full employment. Every month the MPC would meet and change interest rates to nicely meet targets for growth and unemployment. To a large extent we were able to do that in the late 1990s and early 2000s (though this hid an asset bubble) Unfortunately, in the real world, there are often times when this simple trade off becomes more difficult, and we have to accept a worse trade-off – without either inflation, lower growth or both at the same time. This is often known as stagflation.

As I mentioned in higher inflation, lower growth, a supply-side shock like rising oil prices can cause lower growth and higher inflation. This presents a dilemma for policymakers. Interest rates can reduce inflation or increase growth, but not improve both at the same time.

Therefore, we sometimes just need to accept there is a worse trade-off. It is not ideal, but, in the short term, there isn’t anything you can do about it.

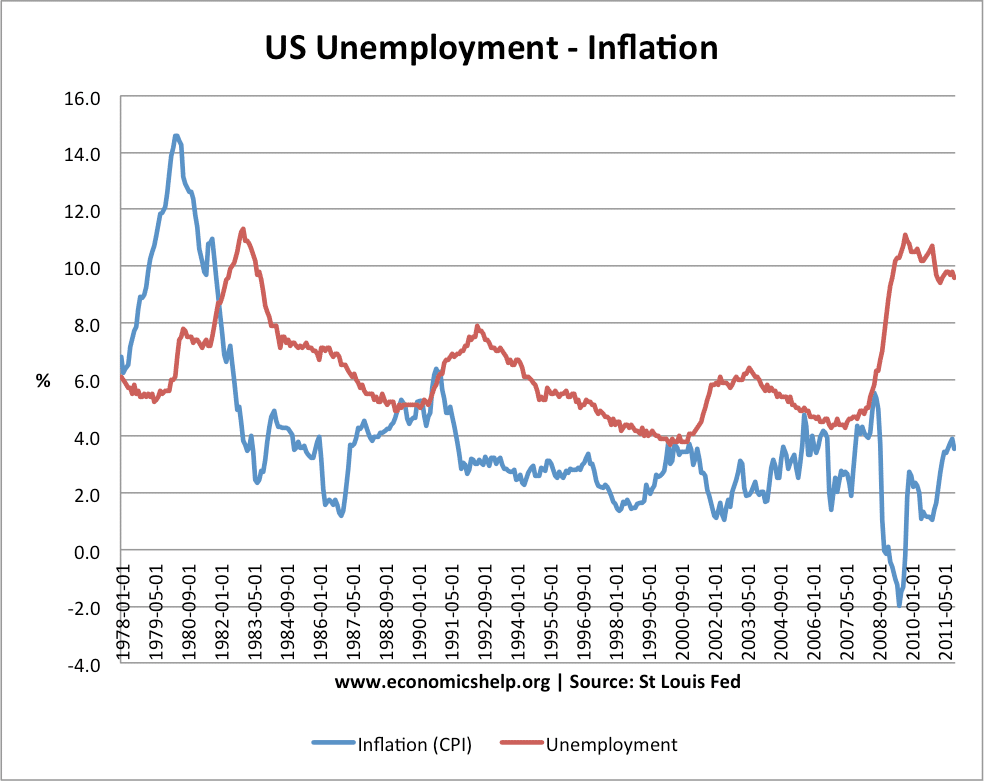

It could be much worse. In the 1970s, we really did have stagflation. (inflation in double digits) and rising unemployment. By comparison to the 1970s, the inflation surge of 3.7%, hardly seems the end of the world.

In recent months, I have rarely agreed with Jean Claude Trichet, of ECB. I feel the ECB is too committed to low inflation in Germany at the expense of wider problems in the Eurozone. However, even Trichet feels that the current cost-push inflation is not something to deflect policymakers, feeling current rates are appropriate.

“All central banks, in periods like this where you have inflation threats that are coming from commodities, have to go through the hump and be very careful that there are no second-round effects,” Mr Trichet said.

What does he mean by Second-round effects?

I think he means that if we get commodity induced inflation, people could respond by demanding wage increases. This wage increase could feed through into permanent wage push inflation. Therefore, even if oil prices stop rising, inflation is embedded in the economy.

However, throughout Europe and the UK, wage inflation is fairly muted in the face of high unemployment. At the moment, there is no wage-price spiral (which did occur in the 1970s)

The ECB doesn’t see any second-round effects “at this stage” and “everybody knows we would not let second-round effects materialise,” he added.

Related