A look at various economic policies to deal with an economic crisis, such as a fall in GDP.

Economic crisis could involve

- Lack of economic growth/recession

- High Unemployment

- Long-term structural deficits

- Lack of confidence in finance and consumer sector.

- Rapid devaluation

Solutions to economic crisis

- Fiscal policy – When the government influences demand through changing spending or taxes.

- Government investment in new infrastructure (e.g. New Deal in the 1930s) helps to stimulate demand and creates jobs.

- Income tax cuts – increasing the disposable income of workers, encouraging them to spend.

- Monetary policy – When Central Bank influences demand and supply of money.

- Cutting interest rates – makes borrowing cheaper and should increase the disposable income of firms and households – leading to higher spending.

- Quantitative easing – when Central Bank creates money and buys bonds to reduce bond yields and

- Helicopter money – when the central bank creates (prints) money and gives it to everyone in the economy.

- Supply-side policies – Long-term policies to try and improve productivity and efficiency in the economy.

- Free market supply-side policies – reducing government intervention in the economy, e.g. lower taxes

- Interventionist policies – government spending on education and training

- IMF bailout – IMF give money to stem the loss of confidence and implement structural adjustment policies, e.g. better tax collection, privatisation, price liberalisation.

- Government bailout of industries/banks. To prevent loss of confidence in financial sectors.

Example – March 2020

In March 2020, the coronavirus has caused a sharp shock to demand – leading to recessionary pressures. It has caused a plummet in the oil price and the stock market falls. Some sectors of the economy have been particularly hard hit – travel, leisure, the gig economy. It is not known whether it will prove a temporary blip or turn into a full-scale recession. What is the best response to this crisis?

- Interest rate cut – The Bank of England and the Federal Reserve have cut interest rates. This will provide some relief to businesses and homeowners (they will have lower mortgage costs). However, it is unlikely to stimulate demand or make that much difference. In a difficult climate, business won’t start investing because of a minor cut in interest rates. Many gig-economy workers will not notice the interest rate cut. In essence, the interest rate cut is outweighed by negative sentiment.

- Income tax cut. Proposed by the White House, a payroll (income) tax cut increases disposable income and in theory, may encourage spending. However, an income tax cut doesn’t help those most affected by the crisis. Those made unemployed or the self-employed who see a fall in income. Also, many householders will probably save the tax cut – because of low confidence and uncertainty.

- Helicopter Money. This involves the Central Bank creating money and giving a fixed amount to everyone. This avoids means-testing and means those badly affected will get some income. In normal circumstances, printing money causes inflation. But, at the moment, there is a greater threat from deflationary pressures.

- Higher unemployment/sickness benefits. Higher benefits for those sick or unemployed – and make it easier to claim benefits. This will make big difference to those on the fringes of the economy. It will enable them to keep spending and pay their rent. Higher benefits are disliked by those who think it creates disincentives to work.

- Expansionary fiscal policy – Higher spending on public investment can kickstart the economy. But, this is a slow policy to act.

- Rent relief/mortgage relief – – Since this may prove to be a very short-run but steep crisis, the other option is to force banks to allow those with lost income to delay paying rent/mortgage relief or the government can offer relief on tax bills and rates. This could make a difference between bankruptcy and surviving for firms on the edge after fall in demand.

To some extent, there are no policies that can prevent a slump in demand, when you get a crisis like this. But, the government can

- Mitigate the effects for those left with no income – direct payment, rent relief, tax relief

- Prevent the temporary slump turning into larger-scale recession – if the private sector cuts back investment, there is a role for both monetary and fiscal policy to provide additional demand.

Example of 2008/09 Recession

The first policy response was a cut in interest rates. In the UK, rates fell from 5% to 0.5%

In theory, lower interest rates make borrowing cheaper, and this should encourage consumption and investment. In the long term this may lead to higher growth.

However, cutting interest rates was not particularly effective in 2008/09. This was because

- Interest rates were lower but banks didn’t want to lend – there was a shortage of funds.

- Time lags involved – homeowners on fixed rate mortgages don’t notice for perhaps 2 years.

- Consumers had an inelastic response to lower rates, people didn’t want to spend because of economic climate

There was also a government bailout out for banks to prevent a loss of confidence in the financial system. This was a significant factor in preventing the crisis escalating.

Fiscal policy

In 2009 the UK, the government cut the rate of VAT to provide a fiscal stimulus.

In the US, there was a modest fiscal stimulus from the Obama administration.

The US also agreed to bailout large car firms which were at risk of going bankrupt. Bailing out car firms cost a lot, but it prevented a further rise in unemployment in the car and related industries.

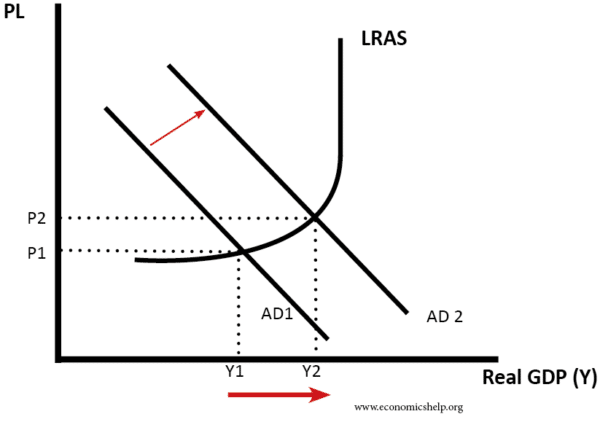

It helped mitigate the effect of falling income and provide some receovery. In theory, lower taxes should increase consumer disposable income and therefore help increase Aggregate Demand (AD).

The recovery in the US was strong than the Eurozone, where governments were more concerned about levels of government borrowing and there was no real fiscal stimulus.

The drawback of fiscal policy is that developing countries may already have large public debts and therefore they may be nervous about borrowing more. In the Eurozone this was a big factor.

Fiscal policy can also be ineffective in increasing AD, for various reasons. See: limitations of fiscal policy

Supply Side Policies

Some economic crisis arise from structural problems in the economy. For example, they may involve

- Corruption and failure to raise sufficient tax revenue

- Lack of competitiveness (e.g. rising wage costs)

- Poor productivity growth

- Low levels of education and training

In these cases, countries may not just need an increase in Aggregate demand, but also to reform the supply side of the economy to improve competitiveness. Therefore, it may be necessary to pursue policies such as:

- Education and training – increase skills and mobility of labour.

- Reduce the power of trades unions and minimum wages to reduce labour costs

- Reduce labour market protection which increases costs of labour and discourages firms from employing workers.

- Privatisation and deregulation

Devaluation

Devaluation is a policy to reduce the value of the exchange rate. This has the advantage of:

- Reducing the cost of exports and improving competitiveness

- Helping to boost export demand and therefore increase aggregate demand and economic growth.

For example, countries in the Euro-zone such as Italy, Greece and Spain have suffered from a decline in competitiveness which has contributed to lower growth and higher unemployment.

The drawback of devaluation is that it can cause inflationary pressures, but if an economy is experiencing low growth, then inflation may not be a problem.

Dealing with a debt crisis

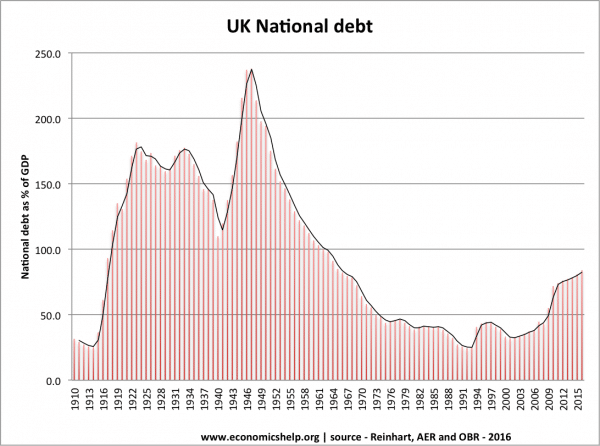

UK National debt – grew significantly during First and Second World War – long period of economic growth enabled the economy to pay off debt.

Many countries are making the mistake of trying to solve long term structural deficits, by sacrificing short term growth. In the name of long term structural change, governments are deflating the economy at a time when they should be doing the opposite.

The UK and US should be setting out plans to reduce the long term deficit, but this should not be involving short term cuts in spending on important capital investment. These long term policies should involve:

- Raising retirement age in response to an ageing population.

- Evaluating automatic health care spending in the US.

- Seeking to move people off long term benefit (e.g. helping those on disability allowance find less taxing jobs)

- Planned tax rises which are appropriate for incentives, efficiency and equality. e.g. US should be planning to raise tax on petrol, and tax on those high income earners who have befitted from recent tax cuts.

These kind of policies are sustainable and actually, make a big difference to long term budget situation. If you sell off assets or stop current capital investment projects, it is a very limited benefit to the long term budget. But, if you make changes to retirement age or entitlement spending this isn’t just a one off benefit, but a permanent improvement to the government’s fiscal position.

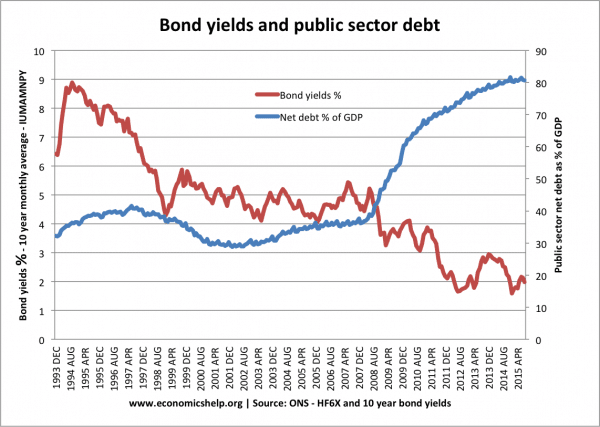

Bond yields in the UK and US are near record lows. If the government came up with plans to improve long term budget situation over next 20 years, markets would be willing to lend for short-term economic recovery.

Higher debt leads to lower bond yields (lower borrowing costs)

See also: