Resale price Maintenance RPM used to be a common practise for manufacturers to set a minimum price for retailers to sell their goods. In the UK, the use of RPM was quite common in the post-war period from clothes to books, records, clothes and electronic goods. It ensured a minimum price of resale and avoided price competition. However, in recent years it has rapidly disappeared from the UK economy.

This post was inspired by Robert Peston’s BBC documentary – Robert Peston goes shopping because it reminded my how common RPM used to be.

The logic of resale price maintenance is that:

- It helps retailers to be more profitable. Manufacturers may like this as they feel that if they keep retailers profitable, then retailers are more able to keep selling their goods.

- It prevents damaging price wars with retailers under-cutting each other in a race to the bottom.

- Provides support for smaller retailers, who cannot buy in bulk, to remain profitable. For example, small bookshops benefited from a RPM for books because they can’t benefit from purchase economies of scale. Since the removal of RPM on books, many smaller independent retailers have gone out of business, losing out to large scale distributors like Amazon.com

- It enables manufacturers to reward shops who promote their product through advertising. It also enables manufacturers to invest more in future products. For example, since the end of RPM in books and music, the industry claims it has lost some types of investment in music production and in the promotion of authors.

- RPM can also reward firms who provide a high quality of personal service. For example, without RPM, consumers can take the free advice of knowledgeable sales assistants and then go and buy online from a cheaper provider. In effect the online retailer who doesn’t offer any service is free riding on the ‘bricks and mortar’ shops who can offer a personal service.

- Consumers don’t have to waste time searching around for the best deal. They know the price will be the same where-ever they buy it.

Criticisms of RPM

- It artificially inflates prices, leading to a decline in consumer surplus and gives consumers less discretionary income to spend on other goods. It is allocatively inefficient as the price is likely to be above marginal cost.

- Artificially high prices may reduce incentives for manufacturers to remain internationally competitive. RPM enables an easy profit margin in domestic markets, but the result is that inefficient manufacturers may stay in business and lose the market incentive to cut costs and become more efficient.

- For example, when Dixon’s started to import cheap cameras from Hong Kong in the 1960s it was able to undercut British manufacturers who had relied on the old RPM to remain profitable. British manufacturers who had been protected by RPM in the domestic market started to go rapidly out of business when cheaper imports were bought in. RPM had masked their decline in competitiveness.

Conclusion

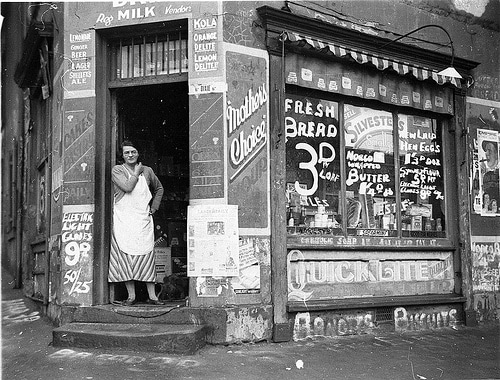

It seems almost quaint the idea that goods have a minimum price set by manufacturers. It’s hard to imagine in the current culture of shopping around on the internet for the cheapest products.

In the 1950s and 1960s, RPM was perhaps one factor in propping up inefficient manufacturers. It didn’t help provide the right market incentives for the long-term performance of UK manufacturing.

However, although it’s hard to support the basic principle of RPM, very cheap internet goods has created some unfortunate side-effects. Many small retailers and retailers who offer high quality of personal service have lost out. It means the High Street is having an increasingly small choice of independent shops. The retail sector is increasingly moving towards lower cost online purchase, but the drawback is we lose some personal service, we may start to regret. But, at the same time, it’s very hard to imagine any reversal and a return to RPM. If nothing else, the internet has made it almost impossible to enforce anyway.

UK history of RPM

- In 1955, the UK recommended that resale price maintenance when collectively enforced by manufacturers should be made illegal, but individual manufacturers should be allowed to continue the practice.

- In 1964, the resale price act considered all forms of resale price maintenance to be against the public interest, unless it could be proved otherwise. Cases were evaluated on a case by case basis. Though many were still allowed.

- In the 1960s and 1970s, retailers increasingly find ways around RPM by introducing their own brand of goods. For example, large supermarkets like Sainsbury’s introduced their own brand of goods so that they could avoid the RMP of established manufacturers.

- In 1997, resale price maintenance on Books was abolished. (also known as the net book agreement) (this was one of last RPM to be maintained)

- In 2010, the OFT investigated allegations of resale price maintenance in the hotel industry. Discount hotel sellers like Skoosh complained they were forced to raise prices (BBC link)

Related