Cognitive bias occurs when an individual person makes an ill-informed decision – often result from past preferences and deeply held beliefs. Cognitive bias means individuals diverge from rational choice and are influenced by non-economic factors, such as emotion and invested opinions.

For example, an economist who supports tax cuts is more likely to concentrate on economic data which supports their claim about how taxes lead to increased revenue.

However, an economist who is more sceptical about the benefits of tax cuts could find data which supports their beliefs.

Cherry-picking data

In economics, there is always the scope to ‘cherry-pick data’

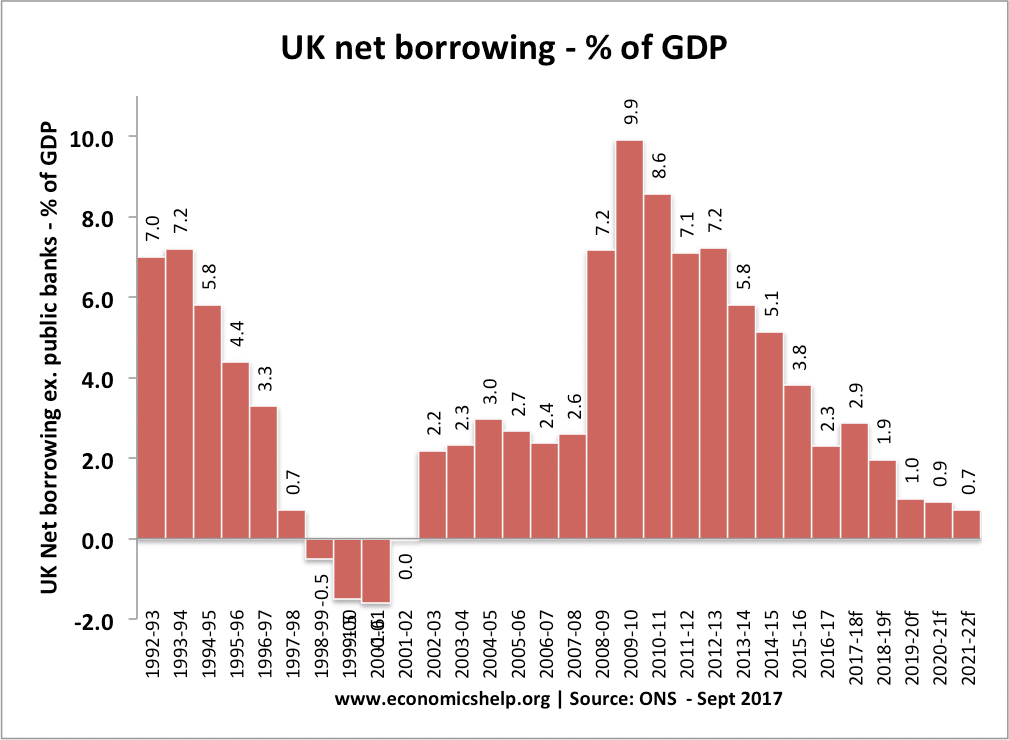

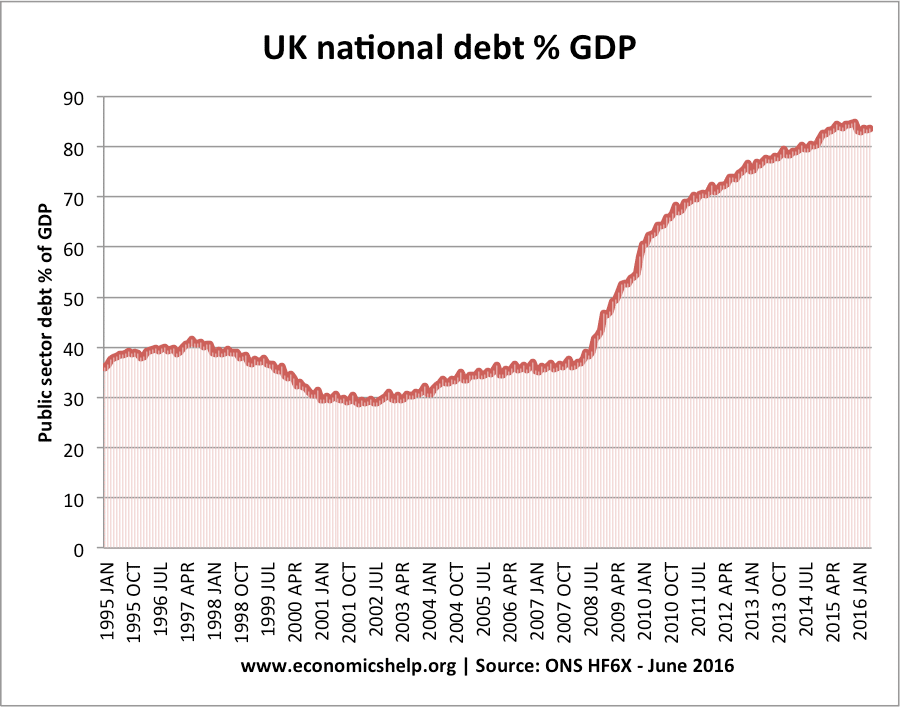

Fall in borrowing – rise in debt

In the period 2011 to 2018, total debt rose. However, at the same time, annual borrowing fell. You can say total debt was rising at a slower rate. However, from the same data, you could choose two very different newspaper headlines.

- ‘Sharp fall in UK net borrowing.’

- ‘UK debt rises to record levels.’

Both statements are correct. But, they give different impressions about the state of UK public finances.

Rise in debt

Other sources of cognitive bias in economics

Availability bias. If something is repeatedly frequently by mainstream media. For example, ‘debt is too high’ is often more politically appealing than Keynesian economics which states that borrowing may be necessary for the state of the economic cycle.

Understandability. Keynesian economics which states borrowing may desirable to offset a fall in private sector spending. Is not intuitive. When we make a comparison to our personal situation, high debt seems bad, so it is harder to make a comparison to macro-economics where different principles apply.

Sunk-cost bias. If we invest in a project, then human nature wants to make our project succeed. However, economics suggests that we should let former sunk-costs go, but consider the marginal cost and marginal benefit of a project. If we have spent £10,000 on a project, then this £10,000 is gone. We shouldn’t persevere just to try and get back the £10,000. However, this decision to invest can weigh heavily on our mind and counter-act the marginal benefit of the decision. See Sunk cost fallacy.

Related