The sunk cost fallacy is when we continue an action because of our past decisions (time, money, resources) rather than a rational choice of what will maximise our utility at this present time. For example, because we order a big meal and have paid for it, we feel a pressure to eat all the food.

“The sunk cost effect is manifested in a greater tendency to continue an endeavor once an investment in money, effort, or time has been made.”

Hal Arkes and Catherine Blumer. (1985), The psychology of sunk costs. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 35, 124-140.

Definition of sunk costs

A sunk cost is an irretrievable cost. It is a cost that we cannot get back. For example, if we spend $1 million on advertising ‘mini-discs’ you cannot reclaim this money from advertising agencies. If you buy a factory, you will be able to sell the capital and reclaim some money.

Making decisions at the margin

An important issue in economics is making decisions at the margin. What are the marginal benefits and marginal costs of deciding to continue with investment? When we make decisions at the margin, we discount any sunk costs. Because these historic costs do not affect future marginal benefits and marginal costs.

“It’s no use crying over spilt milk”

It is like the analogy of ‘no use crying over spilt milk’ Once the milk is spilt, we can’t change that action. If someone wasted money in the past, that action cannot be changed, we need to focus on the best decision at the present moment.

Sunk costs in business

In business, a sunk cost fallacy can cost a business greater financial losses. For example, suppose a firm invested $1bn in research for developing a more efficient CD player, it may feel that because it has invested $1bn, it should continue with more research until it can bring it to the market and get something back for this $1bn. However, if CD’s are no longer selling, it would be more rational to write off these sunk costs, rather than wasting more money on developing a product which will never make a profit. However, if managers were attached to past investment they would keep going – even though it leads to bigger loss in the future.

Examples of Sunk Cost Fallacies

- Using a product to get your money’s worth. Suppose you take out a 12-month gym membership, costing $40 a month. You have committed to spending 12*$40 = $480. Once you have signed your contract, you have effectively committed to $480. It is now a sunk cost – you can’t get it back. Whether you go to the gym or not, makes no difference to the sunk cost.

Now, suppose you injure your arm, the utility maximising decision would be to not go to the gym. However, because of the investment of $480, we may feel we need to ‘get our money’s worth’ and therefore, we go to the gym even though we would actually be better off resting at home.

Of course, some people may take out a gym membership because they know if they commit to spending $40 a month, it will create an incentive for them to go and work out!

2. Investment in ‘white elephants’ or ‘Concorde Fallacy’

Concorde was a supersonic passenger jet, which was a joint project between the French and British governments. After a period of significant investment, it became apparent that the project was likely to be a bad financial investment. Costs were high, and revenue was limited. However, because a lot had been invested in the project already, it was decided to continue with the project causing further financial losses – rather than writing off the sunk costs and accepting initial financial losses. (There were also political reasons for continuing with investment, such as Britain’s entry to the Single Market)

Pursuing a career because of an investment in education

Suppose, you spend seven years gaining a degree and qualifications to be a lawyer. The investment in education is now a sunk cost (in terms of time and money). However, once qualified, you find you don’t like the job and want to do something different like open up a cafe. If you wish to honour the sunk costs of education, you will continue to work as a lawyer, despite not enjoying it. However, if you ignore these sunk costs, you are free to make a choice about which career you prefer to do.

Honouring purchase because of a cost

Suppose you bought a ticket for a concert at $100. However, on the night of the concert, you remembered you have an exam the next morning. The $100 is a sunk cost – you can’t get it back. However, you feel, that since it cost so much you should go – otherwise you’ve wasted $100.

However, if you had been given the ticket for free, you would find it much easier to stay home and revise – because you don’t have any attachment to the ticket.

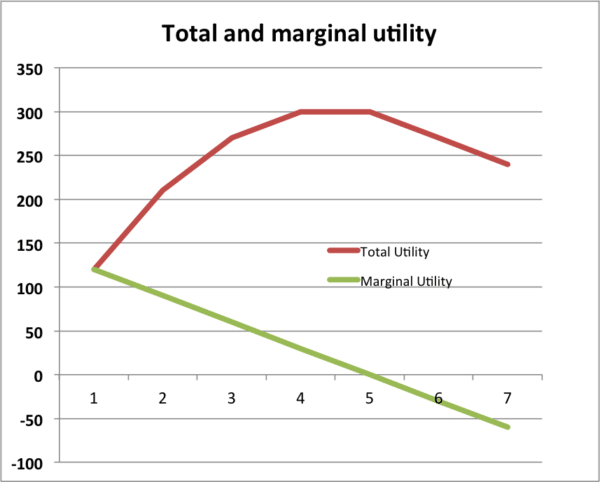

Example – 7 cakes

Suppose you buy seven cakes for £5.00 costing £35.00 – how much should you eat?

- The 5th cake gives zero marginal utility – total utility stays the same.

- But the 6th cake gives negative utility – 30 utils.

- If you eat the 6th and 7th cake because you have bought it, you are making yourself worse off.

- It is better to throw away the last two cakes. The fact you spent £10 on them is no longer relevant.

Related concepts

Mental accounting – developed by Richard Thaler. This states that we hold different views of goods depending on how we received it. If we pay $100 for a ticket, we feel a strong attachment to using the ticket. However, if we receive the ticket for free, we are more likely to ignore its market value, but decide which gives us most utility – staying at home or using a ticket.

Prospect theory – “An essential feature of Prospect Theory is that carriers of value are changes in wealth or welfare – rather than final outcomes.” and “Losses loom larger than gains.” This can explain why we may not want to sell a house at a loss even if we might be better off.

Is the sunk cost fallacy always a fallacy?

Ryan Doody argues it is not always irrational to make decisions because of sunk costs. Doody argues that if we invest in a project, we may wish to continue with investment to hide our flaws and exhibit a strong reputation. If a firm invests in a high profile project, it may be better to make continued losses rather than the reputational harm of admitting it made a failure.

“Acting so as to hide that you’ve suffered diachronic mis-fortune involves striving to make yourself easily understood to others (as well as your future self) while disguising any shortcomings that might damage your reputation as a desirable teammate.”

Economic studies

- Psychology of Sunk cost – Hal Arkes and Catherine Blumer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 1985, vol. 35, issue 1, pages 124-140

Related

- Types of cost

- Contestable markets – a market with low/zero sunk costs

Hi Tejvan,

Thanks for referencing my work!

My website has changed, so the link to my paper no longer works. It can now be found here instead: http://rdoody.com/SunkCostFallacyIsNotaFallacy.pdf

(Or the published version can be found here: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/ergo/12405314.0006.040?view=text;rgn=main)

Thanks again!

Best,

Ryan Doody

Thanks have updated link

Question about the sunk cost fallacy. If you have invested money in a project and are deciding whether to continue to invest, when you look at returns should you look at the return on the incremental dollars you would be investing and ignore what you already put into it? It’s kind of the opposite of the examples you usually see.

Yes. Generally you should make a decision based on revenues and costs and ignore the lost sunk costs.