Readers question: “Can an economy achieve low unemployment, low inflation and economic growth at the same time?”

To achieve low unemployment, low inflation and economic growth at the same time is possible. For example, the UK economy 1993-2006 saw a prolonged period of low inflationary growth. Since early 2000, the Chinese economy has been growing at a rapid rate, with inflation staying relatively muted (with some exceptions, e.g. 2008)

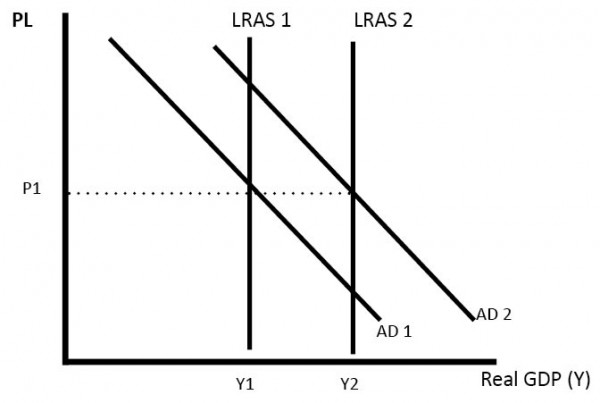

For low inflation and high economic growth to occur, we need to see growth in aggregate demand and aggregate supply (productive capacity). In particular, the growth needs to be sustainable and avoid a boom and bust cycle.

Simple AD/AS diagram showing a rise in both AD and LRAS.

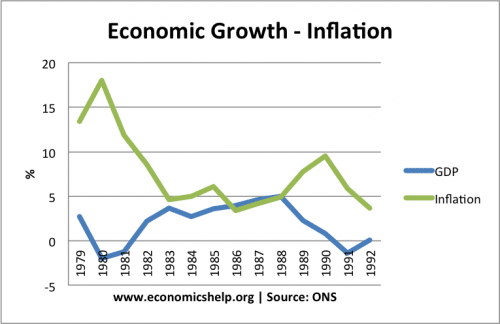

For example, if we have a long-run trend rate of 2.5%, we need economic growth to be close to this. If monetary policy is too loose and growth increased to 4 or 5%, then we would see low unemployment, but inflation would start to rise, and this high growth rate would be unsustainable. We would be likely to see a situation like the late 1980s in the UK when above-trend rate growth led to inflation and then a recession.

Economic growth of 5% in 1987 and 1988, led to a rise in inflation, causing the recession of 1991.

Other factors that are needed for low inflationary growth

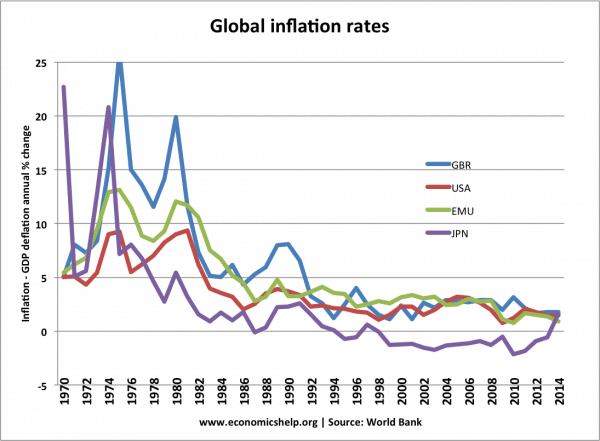

Low cost-push factors. In the period 1995-2006, we see low global inflation. This was partly due to low oil prices and muted commodity prices. With downward pressure on costs and prices, these made it much easier for economies to experience economic growth without inflation.

By, contrast, if you look at periods of rising oil prices/commodity prices, it is very rare to see low inflationary growth. The rising oil prices feed through to both higher cost-push inflation and lower demand.

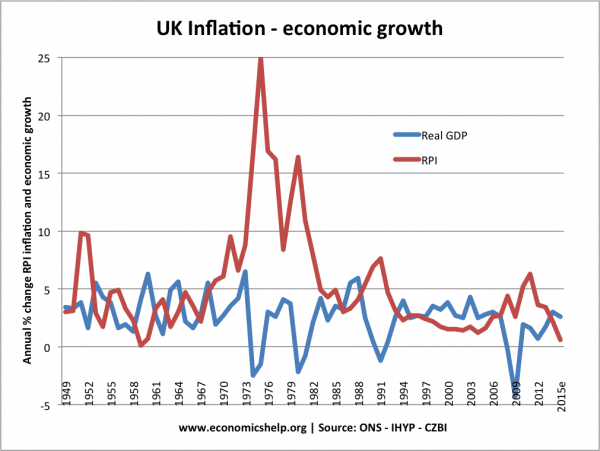

UK economic growth and inflation. Very high inflation in the 1970s due to cost push factors – wage rises, petrol price rises. The 1990s and early 2000s were a golden age of low inflation and high economic growth.

Supply capacity

Another important feature determining the possibility of low inflationary growth is the available supply capacity. One success of high growth in emerging economies, such as China and other Asian economies is the relatively elastic supply of labour. As manufacturing capacity expands, firms find it easy to fill labour vacancies as many farmers are willing to move from low paid jobs in agriculture to manufacturing. The elastic supply of labour in China is a significant factor in enabling high economic growth. As the labour market becomes closer to full capacity, wages will start to rise, and this may feed through into higher inflation – challenging the low inflationary growth.

High growth and low unemployment

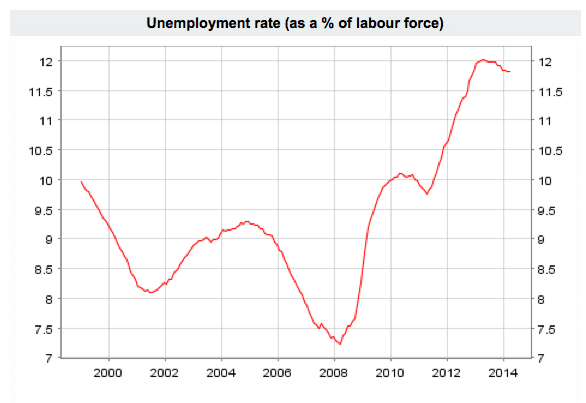

Generally, you would expect a period of stable, sustainable economic growth to reduce the unemployment rate. Higher economic growth will reduce demand deficient unemployment. However, if there is substantial structural unemployment, then we could still see high unemployment rates – despite low inflation and high growth. For example, Europe has struggled with a relatively high natural rate of unemployment in the past decades. Even in 2008 before the economic crisis began, EU unemployment averaged 7.5%

Reasons for high European structural unemployment include inflexible labour markets, mismatch of skills e.t.c

Role of monetary policy in achieving low inflation and high growth

The aim of monetary policy will be to achieve this ‘holy grail’ of high growth, low inflation and low unemployment. In benign circumstances, the Central Bank can use monetary policy to fine-tune the economy. If growth is becoming inflationary, they can increase interest rates. If growth is slowing down, they can cut interest rates. In the 90s and 2000s, Central banks (including the newly independent Bank of England) seemed to be able to hit many of these major macroeconomic variables. However, since the 2008 crisis, they have faced a much more challenging environment. Low growth, high unemployment (and at times cost-push inflation). Due to banking crisis and other structural factors, low interest rates have failed to stimulate economic demand like in previous times.

Conclusion

It is possible to have low inflationary growth and low unemployment. However, it requires more than just successful monetary policy. It also requires helpful external factors – low commodity price increases / improved technology / stable political climate. If these factors are absent, monetary policy cannot do the impossible and create a perfect macroeconomic environment.

Related

How fast can the Canadian economy grow, and at what level can it perform without generating inflation, and therefore higher interest rates? This question has had suprising answers in the United States, and is just now coming to the top of the agenda in Canada. The responsibility for getting the answer right here falls largely to the Bank of Canada.

“The job of the Bank of Canada must be to keep inflation in Canada low and stable. Without that, we will be risking both the economic expansion and the potential productivity gains,” said Governor Gordon Thiessen last week in New York. But Mr. Thiessen well knows that the inflation rate in Canada is the product of many variables, of which the central bank is only one.

In the United States, inflation has not appeared despite high growth rates in consumption, very low unemployment rates and high levels of capacity utilization in firms. The old costly tradeoff between inflation and robust growth has been largely absent, allowing the U.S. expansion to continue into the longest run of the last century. Why?

One core reason is productivity growth, abetted by new technology. The more production that can be generated from a single unit of input, the more the economy can grow without causing supply bottlenecks and rising prices.

The U.S. unemployment rate stands near 4 per cent, yet more jobs are created and filled every month without inciting unusual pressure on wages. One reason for that is the expanding labour force. More people are joining the U.S. labour market as the economy grows, so a rising participation rate expands supply to meet demand.

The United States has also benefited from a strong dollar, which keeps import prices low, and the Asian crisis of 1997-99, which reduced global prices for many goods and commodities. This provided contextual support for the high-growth, low-inflation story in the United States.

Can Canada count on similar forces to support the expansion here as we start to encounter traditional limits to non-inflationary growth? Mr. Thiessen posed that question in New York, answering it with a worried brow: “The Bank of Canada has been concerned about our economy picking up too much speed. There is a risk we could hit the capacity ceiling too hard, causing supply bottlenecks and shortages that could lead to an ongoing increase in inflation.”

Hello, I would like to ask you a question regarding low inflation, low unemployment and high economic growth. I’d like to know how the AS/AD graph would shift and move and how it would look. Also examples of how this could happen and the long run and short run implications.

Thank you.

Abba lerner made a theory that influenced keynes a long time ago. Its about low inflation and unemployment rate at the same time.