Government intervention in the labour market to reduce inequality and market failure can take various forms.

- Minimum wages/living wages

- Maximum wages (rarely used)

- Legislation to prevent discrimination on the grounds of age, sex, religion.

- Legislation to support or regulate trade unions.

- Maximum working week

- Legislation on health and safety

- Behavioural nudges (e.g. encouraging workers to take pensions)

- Government provision of education and training schemes

Minimum wages

The minimum wage sets a legal floor below which employers cannot pay. The minimum wage is designed to help increase the income of the low-paid. The national minimum wage has become a significant feature of government intervention in the labour market because of

- The decline of trade unions,

- A rise in part-time temporary work

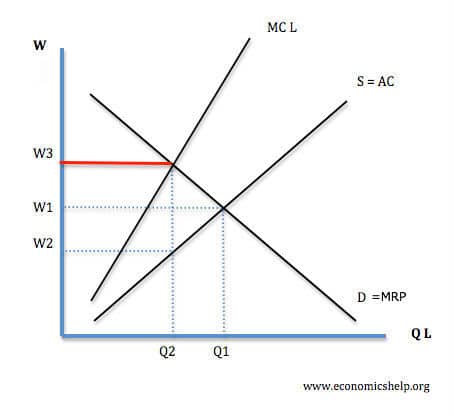

- And a rise in monopsony power of employers.

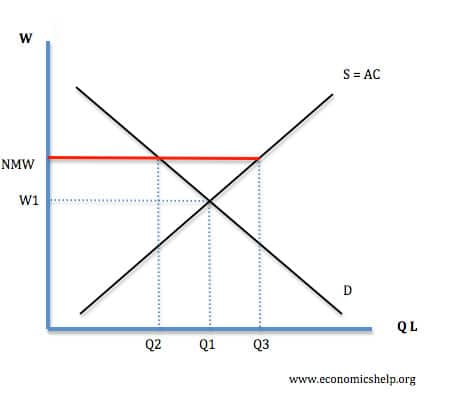

The disadvantage of a minimum wage is that it increases costs for employers and could lead to lower levels of employment as some firms will not be able to afford to pay the higher salary.

Diagram for minimum wage

However, since 1999 the UK government has increased the national minimum wage from £3.60 to £7.83. In June 2018, UK unemployment is near record low-levels. This suggests the government can set a minimum wage without causing unemployment. This suggests that:

- Demand for labour is wage inelastic (firms willing to pay higher wages)

- Higher wages can increase labour productivity (efficiency wage theory)

- Some firms have monopsony power to set wages below the equilibrium.

Therefore, if labour markets are imperfect – if firms have a degree of monopsony power, there is a stronger case for government intervention to set wages.

See more at: National minimum wages

Maximum wages

In theory, the government could set a maximum wage. Up until January 1961, British footballers had a maximum pay of £20 a week – set by the Football Association (not the government).

However, maximum wages have been proposed as a way to limit executive pay. For example, the government could set a limit where the maximum salary for a firm is 20 times the lowest pay. Firms may complain this would make it harder to attract the best staff to important positions.

Legislation against discrimination

- In 1970, the UK passed the Equal Pay Act which outlawed paying different wages for the same job on the grounds of sex.

- The Sex Discrimination Act (1975) sought to promote greater equality of opportunity in training, employment and promotion. It created the Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC) which enabled people to bring cases of discrimination.

- The Equality Act 2010. The Equality Act brought together different acts outlawing different types of discrimination – age, sex, disability, religion, sexual orientation.

In labour markets, firms can engage in discrimination through hiring, firing, paying different wages influenced by non-economic factors, such as race or sex. The Equal Pay Act (1970) was targetted at women who were paid lower wages for doing very similar jobs to men. This targetted obvious sex discrimination, but harder to target is less obvious barriers such as the ‘invisible glass ceiling’ which is suggested a factor for fewer women get promoted to high paid jobs in certain sectors.

The UK government passed a law which, from 2017, made companies of more than 250 employers publish data on their gender pay gap (BBC) – the difference between the average female and male salary. In 2017, the UK gender pay gap was 18.1% for all workers, or 9.4% for full-time staff. By making companies publishing data on the gender pay gap, the government is hoping that the public information will nudge firms into promoting more women to top jobs.

Trade unions legislation

Some governments, e.g. Conservative from 1979-91 sought to reduce the power of trade unions. Mrs Thatcher believed trade unions had too much power and caused economic inefficiency through strikes, wages above the equilibrium and making it difficult for non-union members to get jobs. Other economists argue that trade unions can help increase labour productivity and provide a counter-balance to monopsonist employers.

Like minimum wages, the impact of trade unions depends on the market structure, impact on productivity and sector involved.

Maximum working week

A maximum working week is designed to limit excess work. Governments may also hope a maximum working week could reduce unemployment. The theory is that if workers have fewer hours, the firm will need to employ more workers. France experimented with a maximum working week of 35 hours but in practice, the effect on unemployment was disappointing.

Behavioural nudges

A new form of economic policy is government nudges to change behaviour. A good example of this is the policy to encourage take up rates of private pensions. By making a private company pension a default opt-in – the government has significantly increased take up rates of private pensions.

Government provision of education and training schemes

Perhaps the most important type of government intervention. The government provide basic education for free. This provides a more skilled workforce to increase labour productivity and overcome market failure.

In addition to academic education, there is a strong case for the government to provide more vocational training and support for apprenticeships which help bridge the skills gap in the economy and overcome market failure in under-provision of training schemes for workers.

Related

Very interesting article, I love economy, so I think this topic is urgent in our days

Thank you so much

I need your help more and more

May the dear Lord bless you