Readers Question: The Labour party, among others, protests about the effects of government austerity policies on ordinary people but does government spending, even so-called ‘investment in infrastructure’, not automatically increase national debt which means punishing future generations?

Firstly, if a government increases spending without any corresponding increase in taxes, then this change in the government’s fiscal stance will, ceteris paribus, lead to higher government borrowing – at least in the short-term.

However, in the long-term, we need to consider the effect of:

- Impact of borrowing on economic growth – and future tax returns.

- Cost of borrowing – bond yields

- State of the economy – is the economy close to full capacity (in which case extra borrowing may cause crowding out) or is there spare capacity?

- How effective is the investment in improving the supply side of the economy?

- What does the government borrowing e.g. is to finance pensions or invest in improved infrastructure?

Long-term effects

An important factor is the effect of government spending on economic growth. Suppose the UK has a transport bottleneck, which is causing congestion, higher cost for business and time lost. In this case, judicial spending on infrastructure – public goods, such as better roads, railways and airport capacity, then this can have a positive impact on the supply side of the UK economy. Removing capacity constraints can enable a higher rate of long-run economic growth. In this case, future generations of taxpayers will benefit from these supply-side improvements, higher economic growth and improved tax receipts.

Therefore, in theory, government investment in public sector infrastructure can have a beneficial effect for future taxpayers – even if there is a short-term increase in government borrowing. You could compare to the analogy of a household taking out a mortgage or a business investing in better machines.

State of economy

Another issue is the state of the economy. If the economy is in recession/weak economic growth, then there will be surplus savings in the economy and high demand for buying government bonds. Keynesian theory advocates government borrowing when there is surplus private sector saving to make use of unused resources.

However, if the economy is close to full capacity, then higher government borrowing is likely to lead to some form of crowding out (government spending takes the place of the private sector). This is why economists are generally critical of the Trump tax cuts – which increase US national debt during a period of economic boom.

Interest rates

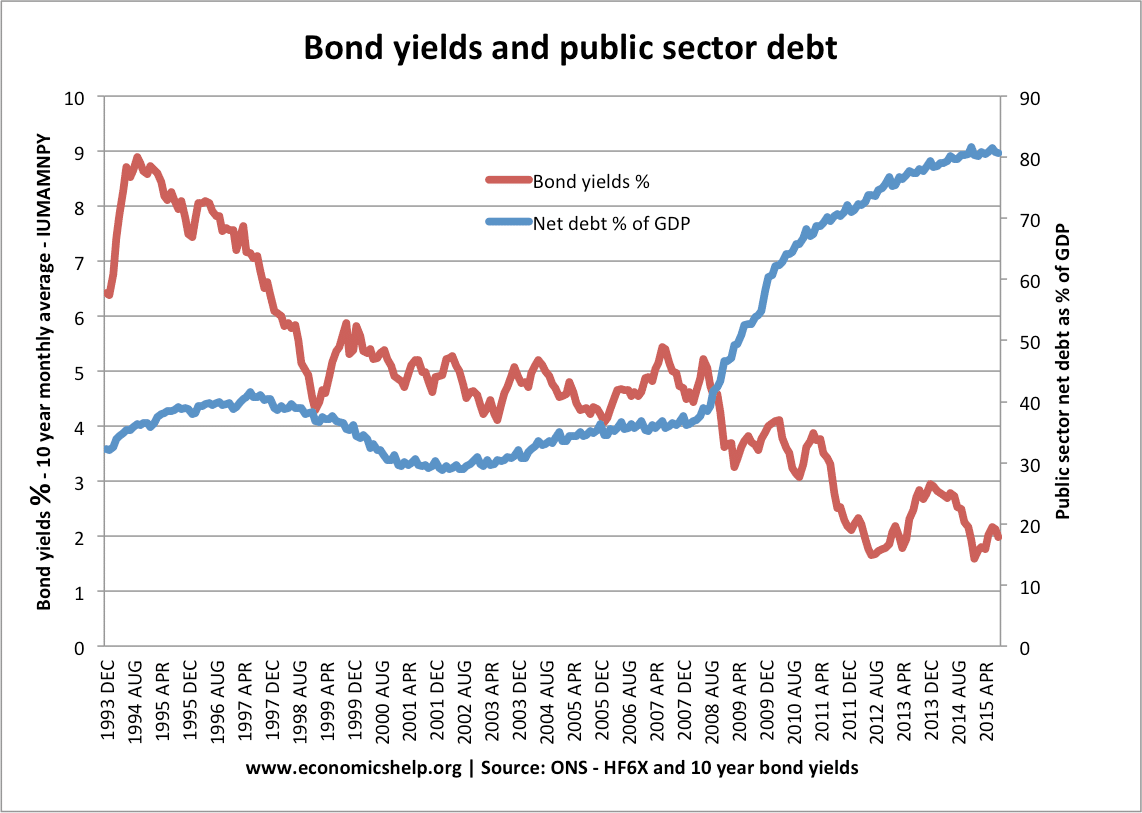

Another factor worth bearing in mind is – what is the cost of government borrowing? Since 2008, interest rates on government bonds have been very low. This makes borrowing relatively cheap, it means government investment projects need a smaller rate of return to still be ‘profitable’ – a rate of return higher than interest rate cost.

However, if interest rates were to return to levels seen in the early 1990s, the cost of servicing debt would be significantly higher and fewer projects would give a higher return than the cost of servicing debt.

Debt as a % of GDP

It is always important to bear in mind the most useful measure of national debt is debt as a % of GDP. If you increase total government debt by 1%, but there is an increase in GDP of 2%, then you are effectively reducing the debt burden – despite that increase in nominal debt.

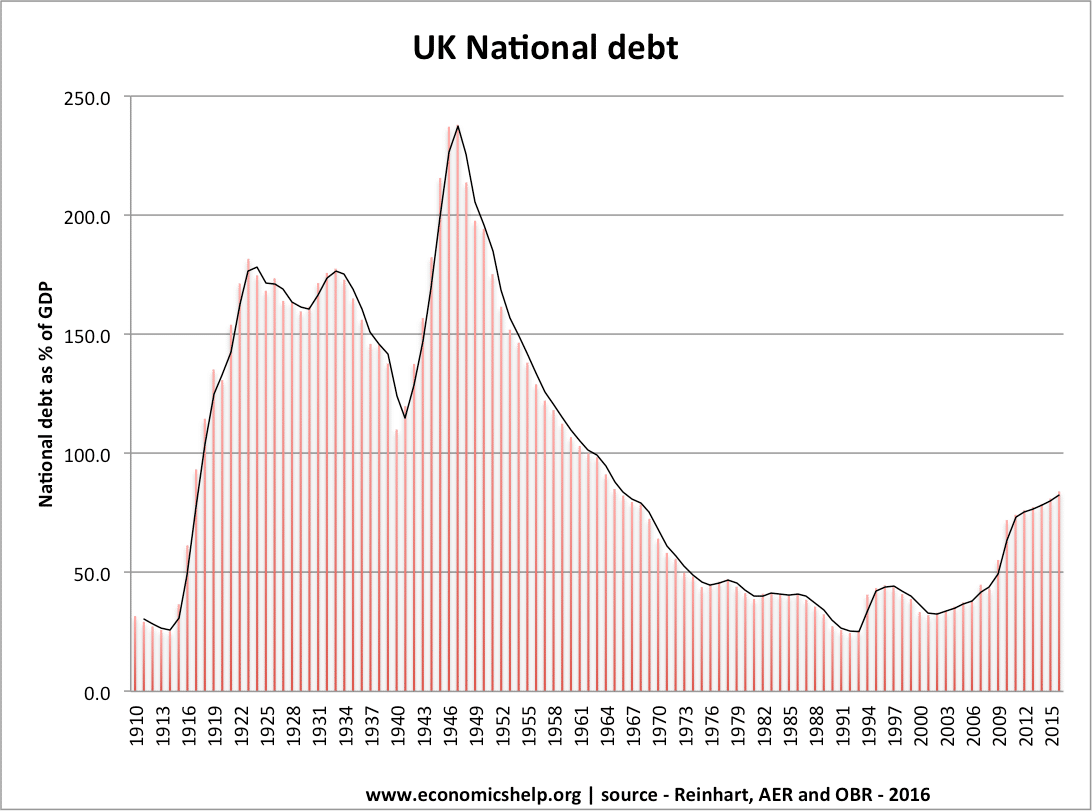

Post-war, the UK had record levels of public sector debt – over 200% due to the cost of war, but also setting up welfare state and building new houses. But, this investment and borrowing proved a good investment for future generations.

When higher borrowing does punish future generations

There are cases of economies responding to economic crisis by increasing government borrowing and financing the increased debt by printing money. If output is falling and inflation rising, and the government responds by printing more money to finance debt, then it can cause hyperinflation. Bondholders will see a fall in the real value of their bonds and will become reluctant to lend the government money. This is a combination of borrowing and inflation, and we can see in economies, such as Zimbabwe (2000s), Germany (1920s)

To complicate matters, in the liquidity trap, 2008-15, UK and US increased the money supply without causing inflation.

Evaluation

There is no guarantee that government spending will automatically improve the long-run rate of economic growth. For example, if the government spent £50 billion on an ineffective railway that was not really used, then it would have limited impact on improving the trend rate of growth and the cost would not be returned by improved tax revenues.

It also depends on other factors affecting economic growth. For example, in the 1990s, a long and sustained period of economic growth, enabled the UK debt as % of GDP to fall – with little austerity. However, since 2008, global economies have generally seen lower rates of growth. This has made it harder to reduce debt to GDP ratios. For some economies in southern Europe, austerity has even been self-defeating.

Related

Great analysis! This was one of the topics I evaluated, recently, in my blog as well. As someone who benefited a great deal from you and your resources during my A-level years, it would mean a great if you could read mine, when you have time, to see what you think (i.e. if you agree?, what I could have done to improve it?)

Here’s the link: https://youngcentrist.com/2018/08/11/three-myths-about-government-debt/

What is your response to those who say that, if a state issues its own currency and that currency is not backed by a commodity (such as gold), there is no need to borrow to finance a fiscal deficit? (Although borrowing may have other economic purposes).

See http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2018/02/09/modern-monetary-theory-in-a-nutshell/

Or

https://youtu.be/6IBEoWSiTHc

I can’t claim any insight, but I can’t see how what you say hear and what Prof Murphy or Stephanie Kelton say can be made to fit together.

Nice article, except that it makes the common claim that government borrowing can be justified if such borrowing funds infrastructure investment. Certainly investment can justify borrowing for a microeconomic entity like a firm, but government is very different. That is, given that government can grab near infinite amounts of money off taxpayers and print a certain amount of money each year, it clearly does not need to borrow to fund investment. Indeed the arguments for government borrowing are feeble in the extreme, as I explain in section 2 here:

http://www.openthesis.org/document/view/603834_0.pdf