In the run-up to the 2016 referendum, Brexit supporting economist Professor Minford wrote: “Over time, if we left the EU [hard Brexit model], it seems likely that we would mostly eliminate manufacturing , leaving mainly industries such as design, marketing and hi-tech. But this shouldn’t scare us.”(Source)

In 2012 Mr Minford said “It’s perfectly true that if you remove protections, the sort that have been given to the car industry and to other manufacturing industries inside the protection wall, you’re going to have a change in the situation in that industry.

“You are going to have to run it down. It will be in your interests to do it, just in the same way we ran down the coal industry and the steel industry. These things happen.” (P. Minford 2012)

Later he clarified these comments saying only some parts of unskilled intensive manufacturing would be eliminated and “the bits of manufacturing that were skill intensive would probably expand”. (Source)

But, in Minford’s model of “Britain alone” – outside the EU, single market and customs union, the car industry would face grave threats. But, does it really matter if the car industry (which employs directly or indirectly 800,000 people) went the way of the coal and steel industry as Minford suggests? After all, the coal industry used to employ 1.2 million people, but nobody believes we should still have a million people going down the mines.

Justification for allowing car industry to decline

Free market economic theory gives some justification for allowing market forces to dictate the nature of the economy. One hundred fifty years ago, 90% of the workforce was employed in agriculture. The process of mechanisation saw jobs lost in agriculture, but new jobs created in manufacturing. When the Luddites smashed up machines in the nineteenth century, they feared the decline of one industry would leave them unemployed. But, despite temporary disruption in some sectors, the total number of jobs continued to rise as new technology led to lower prices and increased demand for a new range of goods. Economists term a fear of job losses from new technology as the “Luddite fallacy.”

Joseph Schumpeter also mentioned the concept of creative destruction – the idea that it is necessary for inefficient industries to decline to enable resources to move to new more efficient industries and enable continued growth in productivity and living standards. Capitalism has been undergoing creative destruction for the past 300 years, and it is foolhardy to think we can prevent it.

EU protection of cars

The EU has tariff protection on the imports of cars from Japan and the US. US motor vehicle exporters face EU tariffs averaging 8.0 percent, including tariffs of 10.0 percent on finished vehicles and 3.0 percent to 4.5 percent on most parts, in addition to a variety of non-tariff measures (NTMs) that further restrict access to the EU market. (Gov. UK)

As of 2018 EU has also had high tariffs (up to 10%) on car imports from Japan.

The result is that the UK pay higher prices for imported cars and give UK car manufacturers a form of protection. In a liberalised world, where the UK dropped import tariffs. UK consumers could buy cheaper cars from abroad. This would leave more disposable income to buy other goods – creating new demand in different sectors. As Minford argues:

” quitting the protectionist EU… should also be accompanied by an 8 per cent fall in prices – which would add an average of £40 a week to such households” (UK Brexit Boost)

But, the drawback for the UK car industry is that removing these EU import tariffs would cause less demand for the UK produced cars as consumers switch to cheaper imports.

Problems with running down the car industry

However, while there is always a case for allowing market forces to dictate industrial change, there are many negative consequences.

Wage inequality. Jobs in the car industry offer relatively well-paid and full-time jobs for manual workers. The decline of the car industry would see jobs shift to new sectors. But, in recent years, new jobs created have been characterised by the gig economy – part-time, temporary, zero-hour contracts, non-unionised and as a result, lower paid. In recent years, wage inequality has increased and real wage growth has been low. According to a study at LSE, this policy could imply

“an increase in wage inequality: skilled workers’ nominal wages increase by around 11%, but unskilled workers’ wages fall by 14% (LSE, PaperBrexit06)

Structural unemployment

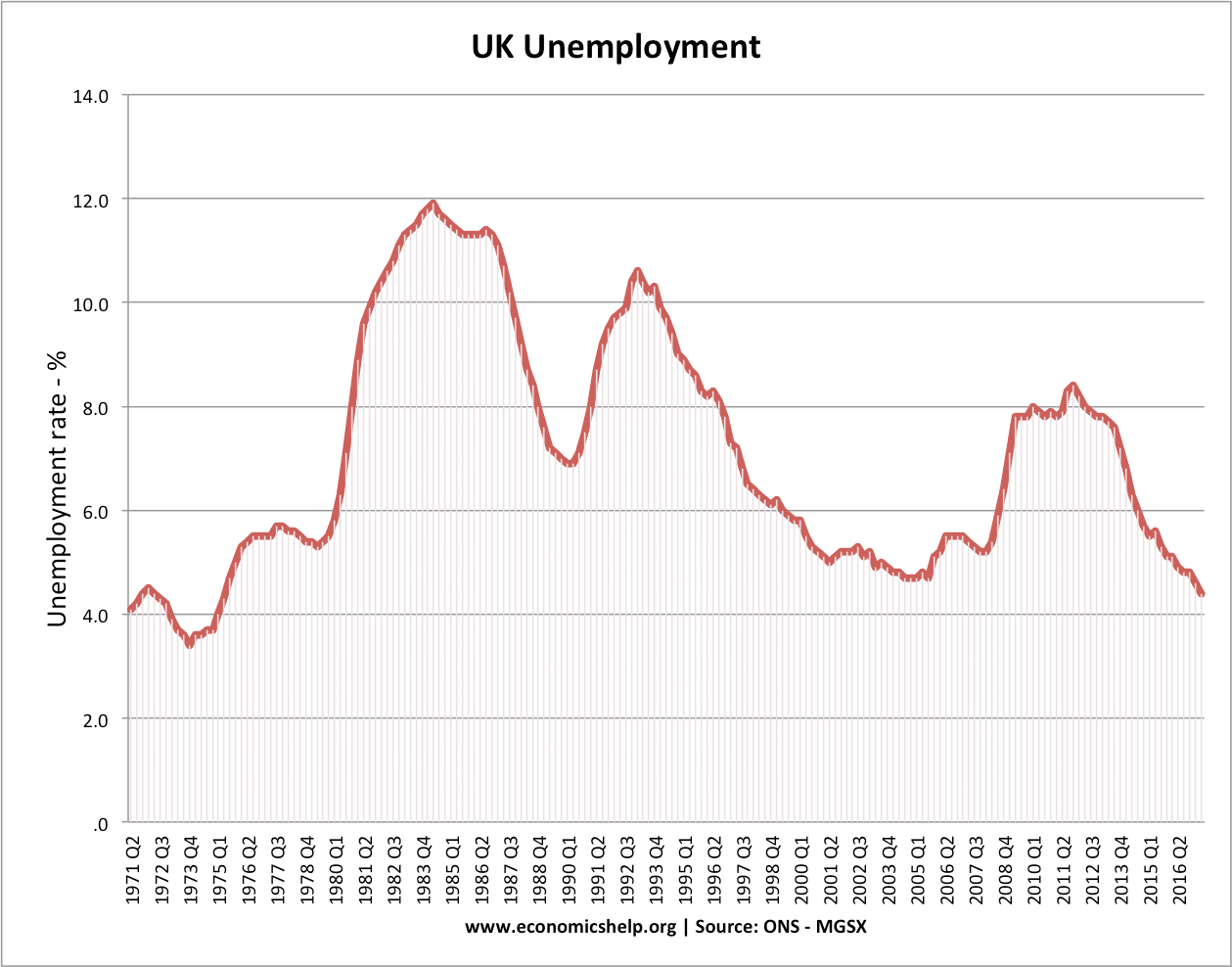

In the long-run, job losses in the car industry will be offset by new jobs. But, the long-run can be several years of economic hardship for those who lose their jobs. The decline of manufacturing in the early 1980s led to several years of persistent structural unemployment.

Even in 1986, with the economy booming, unemployment barely fell below 7%. For those who face long-term structural unemployment, it is little consolation to know the economy is slowly moving to more efficient production methods. This is a real economic hardship, but also a personal cost of not having a job and the effect on life-satisfaction

The car industry is still viable

The UK car industry in 2019 is not like the coal mines in the early 1980s (or even like the car industry of 1970s, pre foreign-investment). UK car firms are some of the most efficient in Europe (helped by inward investment from successful multinationals like BMW and Nissan). The biggest potential cost to the car industry is not removing import tariffs in Japan and the US – but the creation of export tariffs and non-tariff barriers from the UK leaving the Single Market. The UK car industry could survive despite cheaper imports; their key concern is being able to export to Europe and use the European Single market for the import of car parts. Leaving Brexit without a deal would discourage firms from investing in the UK car industry. What car firms really want is the guarantee the UK will stay in the Single Market.

In other words, there is no benefit from running down a viable industry which has good labour relations, and good long-term performance.

Macro-effects

A shock fall in UK manufacturing would affect UK economy growth and could be a factor in causing a recession. Although manufacturing only accounts for 10% of GDP, job losses in the car industry will have real effects on both spending and also confidence.

Balanced economy

On the one hand – to an economist, it doesn’t matter whether exports come from manufacturing or the service sector. In the political world, there is arguably an obsession with manufacturing and a tendency to give it greater value than equivalent output in the service sector. However, leaving the Single Market will also cause costs for the service sector, such as losing passport rights on trading in the city of London. The decline in manufacturing may not be easily offset by improvements in the service sector.

Also, the UK has a persistent current account deficit. Car industry exports and inward investment play a role in improving the UK position. A decline of UK exports of cars and a decline in foreign investment in the car industry would put more pressure on the current account and sterling.

EU Free trade deals

The EU has already signed a free trade deal with Japan, which will see the removal of EU tariffs on imports from Japan. The EU is also negotiating a new trade deal with US which will see free trade in cars. Inside the EU customs union, the UK would benefit from these free trade deals, but outside in the “Britain alone” model, the UK would need to negotiate its own trade deals – which could take many years. Both Japan and the US have said they prefer to make deals with the EU as a whole.

Minford assumes the EU acts primarily as a trade diversion model – placing tariffs on imports to protect domestic EU. But, it ignores the role of the EU in trade creation and the coming free trade deals. Ironically, the UK is leaving the Single Market, just as the EU is reducing import tariffs on imports from Japan and the US

Gravity theory.

In Minford’s model, he assumes frictionless trade around the world – regardless of distance. However, modern trade theory places emphasis on gravity theory – the observation that cost is only one factor out of many. In the real world, countries tend to trade with near neighbours, because of shorter time periods, and similar cultural and business preferences. For example, BMW producing a car in Oxford “UK point out that the crankshaft is made in France, drilled and milled in Warwickshire, and integrated into an engine in Bavaria” A key factor for car companies is having frictionless trade – not just tariffs but the absence of paperwork and customs checks – also this is under threat outside the Single Market.

Conclusion

A government can rarely fight against economic forces in the long-term. If an industry is in terminal decline – like coal and steel, it is an uphill struggle to keep it going. However, if the UK leaves the EU without frictionless trade with the EU, it could cause a needless decline in the car industry – even thought it is relatively efficient. The danger to the UK car industry does not come from reducing EU import tariffs (which the EU is going to do anyway) but the UK losing its free-market access to the Single Market. This would be a welfare loss to the UK economy.

Related