The Lib Dems have proposed a budget rule that would run a persistent current budget surplus of 1%. This means that current spending (day to day costs of government) should always be less than tax revenue.

Borrowing would only be allowed to finance capital investment after an independent watchdog found that the return would be greater than the initial cost.

The argument for running a current budget surplus is that.

- Lower debt. Over time, it will reduce the total amount of public sector debt as a % of GDP

- Lower interest payments. Over time, it will reduce interest rate payments on debt.

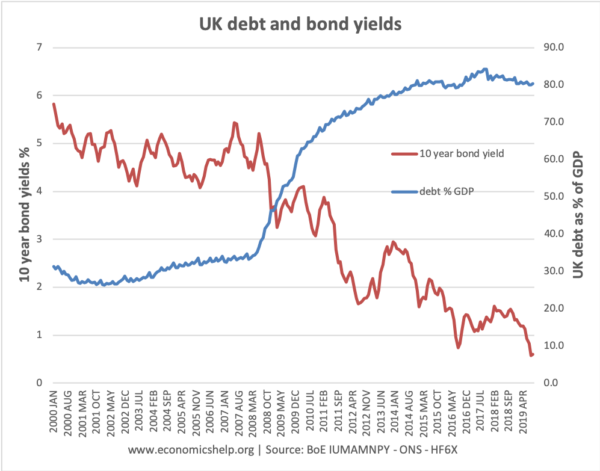

- Lower bond yields. It could reduce bond yields as if the government buys back debt, this will push up bond prices and push down bond yields.

- Avoid spending splurges. It provides a mechanism to prevent politicians from making bold spending commitments that don’t have a source of tax revenue.

- Low inflation. Reducing debt will encourage private sector investors that the government is committed to sound finances and there is no possibility of printing money which would be inflationary.

However, there are many criticisms of proposing a fiscal rule which requires current budget surplus.

Deflationary. A fiscal rule that requires a permanent budget surplus is likely to lead to deflationary pressures in the economy. For example, if the economy enters recession or even a very slow rate of economic growth (e.g. since 2010) then cyclical tax revenues fall, but cyclical government spending (e.g. benefits) rise. This would cause a budget deficit, but under this fiscal rule, the government would be obliged to cut spending or raise taxes in response to the slowdown. But, this would worsen the economic slowdown. Cutting benefits in a recession gives people less money to spend and leads to even lower growth.

- In recent years, interest rates have fallen to zero, meaning that if the government cut spending in a slowdown, there is limited room for monetary policy to offset the fiscal cuts.

- I like the analogy Paul Krugman gave of austerity in a recession to that of medieval blood-letting. The doctors thought that – although it was painful – it was in the patient’s interest – but, it merely made the patient worse. It is the same with austerity in a recession, it may feel ‘the right thing to do’ but it depresses demand and growth even further.

Government debt is not ‘mortgaging our future’ When a government borrows, it involves selling bonds to the private sector (approx 75% UK private sector) like banks and pension funds. The private sector has significant private savings and is currently keen to buy bonds at low-interest rates. Government borrowing is making use of these unused savings. Repaying debt can be done but in practice, it would involve cutting spending on public services and sending cash to (relatively wealthy) private sector investors (who then have to find alternative places to put their cash) It is helpful to think of government borrowing as borrowing money from another family member. We aren’t mortgaging UK assets to borrow from abroad, it is just some family members have surplus cash and are willing to buy bonds to use for useful spending.

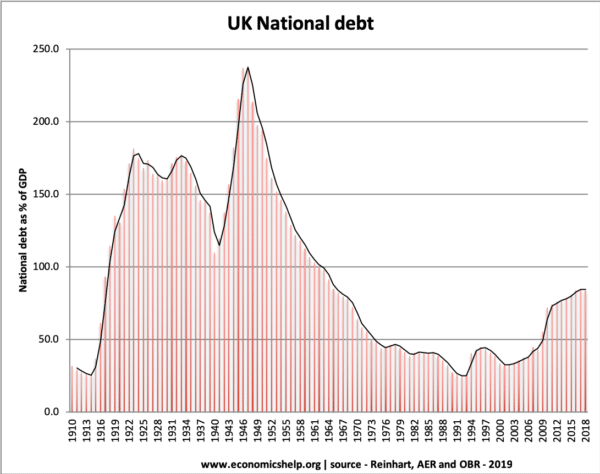

UK national debt

This graph shows that UK debt has been much higher in the past. For example, by 1950, UK debt as a % of GDP was over 200% of GDP. Far from holding back the economy, the high debt corresponded with a long period of economic expansion.

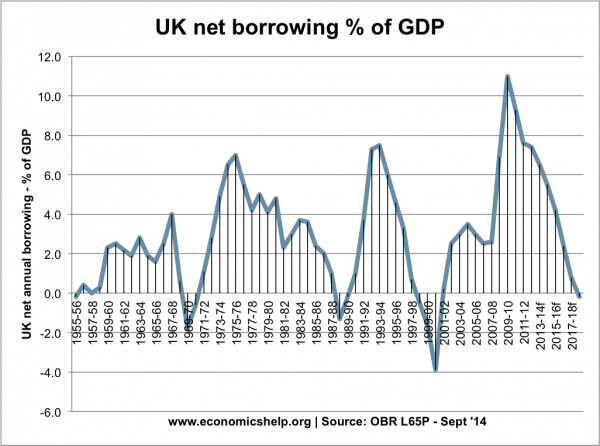

This graph shows the UK very rarely runs a budget surplus. Yet, even though the UK rarely ran a budget surplus in the post-war period, net debt as a % of GDP still fell.

1920s and 1930s Deflation

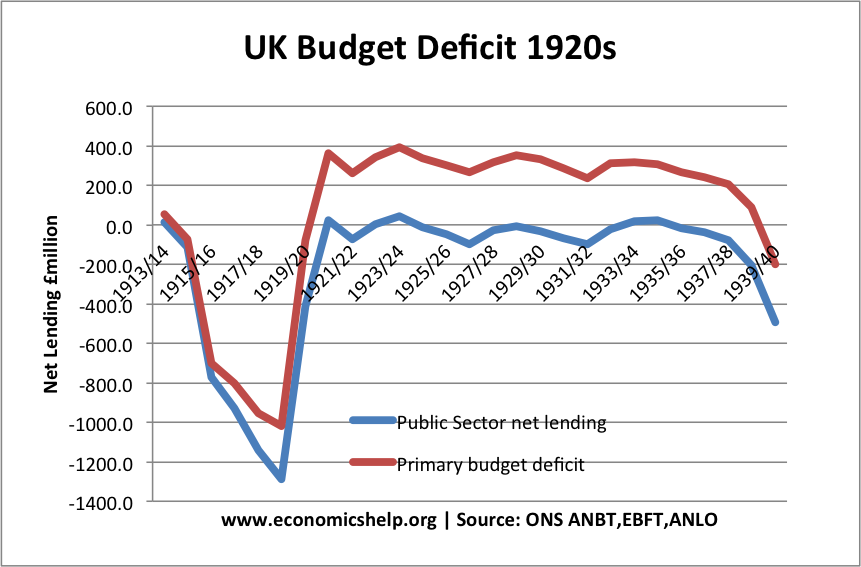

The efforts to run a budget surplus are reminiscent of the 1920s and 1930s. In those decades, the “Treasury View” was that the government should run a budget surplus. In the 1920s, the government pursued austerity and strict spending limits to run a primary budget surplus.

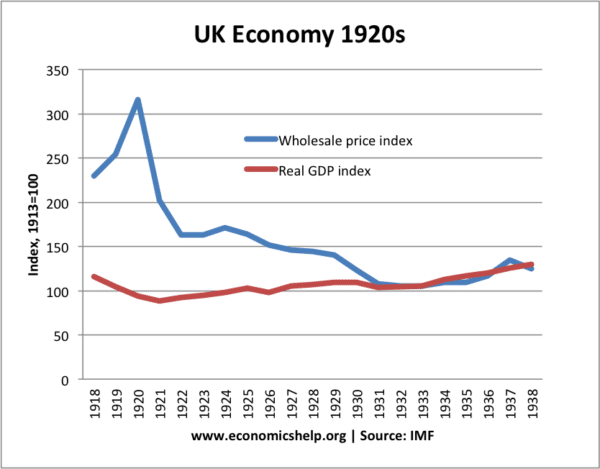

But, combined with high-interest rates, this was a period of prolonged unemployment, deflation and very weak economic growth.

In the 1930s, the Great Depression caused a rise in government borrowing, the Treasury put great pressure on government to run a budget surplus. A coalition government cut unemployment benefits and increased taxes in an effort to balance the budget, but this deflationary fiscal policy was damaging to the economy and exacerbated the recession. It led to Keynes developing his general theory in criticising efforts to run budget surplus in recession. This is why fiscal rules like the one proposed can be highly damaging.

Interest rates are already very low

In the mainstream media, it is often lazily assumed the high debt is ‘unsustainable’ and leads to higher interest rates, but the reality is very different. As debt has increased since the 2009 recession, interest rates have fallen to record lows – showing despite the £600bn increase in national debt under the Conservatives – there is still very strong demand to buy government bonds. The low bond yields are a reflection of low inflation and low growth. With interest rates of 0.5%, there is no need to pursue austerity to prevent high-interest rates.

- One thing with the proposed fiscal rule is that if the return is greater than the cost, then this means capital investment is fine. But, if interest rates are 0.5% – there will be a huge number of projects which do give a greater return than the very low cost.

Does government debt really place a burden on future generations?

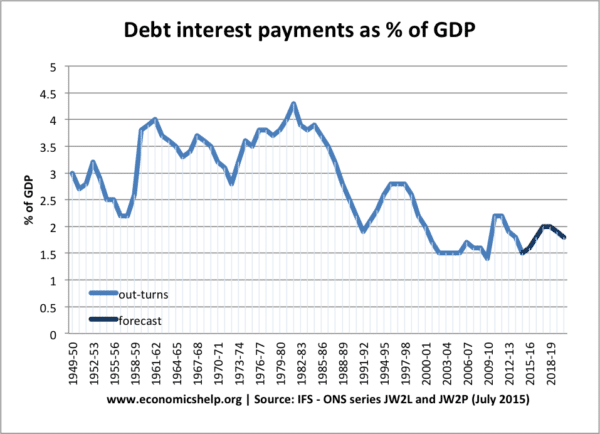

No. Future generations will benefit from the capital investment (broadband, internet, environmental investment). Also, the cost of servicing national debt is a relatively small percentage of tax revenue.

The real cost of servicing national debt is the debt interest payments as a % of GDP. This graph shows that they have been fairly constant around 3% and in recent years, debt interest payments as % of GDP have fallen (due to lower interest rates). These debt interest payments could be reduced by paying off debt.

Inflation

It is more important to target inflation than government borrowing. If inflation is very low, this suggests need for expansionary policy (be it fiscal or monetary). If inflation is high, there is much greater justification for trying to run a budget surplus

Evaluation

Running a budget surplus can be a good thing to do. When the economy is growing strongly, the government should be aiming to run a current budget surplus. But, it is a mistake to make an inflexible rule out of it. There is no magic payoff to running a budget surplus; there is no current need to worry about government debt. Given unusual economic circumstances (interest rates close to zero) the cost of borrowing is very low, and the benefits of paying back bonds very low.

This is not to say governments should ignore debt. If a fiscal policy rule is desired a much better policy is to aim at long-term debt stabilisation of around 60-70% (for example). Aiming at long-term debt stabilisation is much better than focusing on annual deficits.

Related