Slowbalisation – a phenomena which involves a slowing down of the pace of global integration.

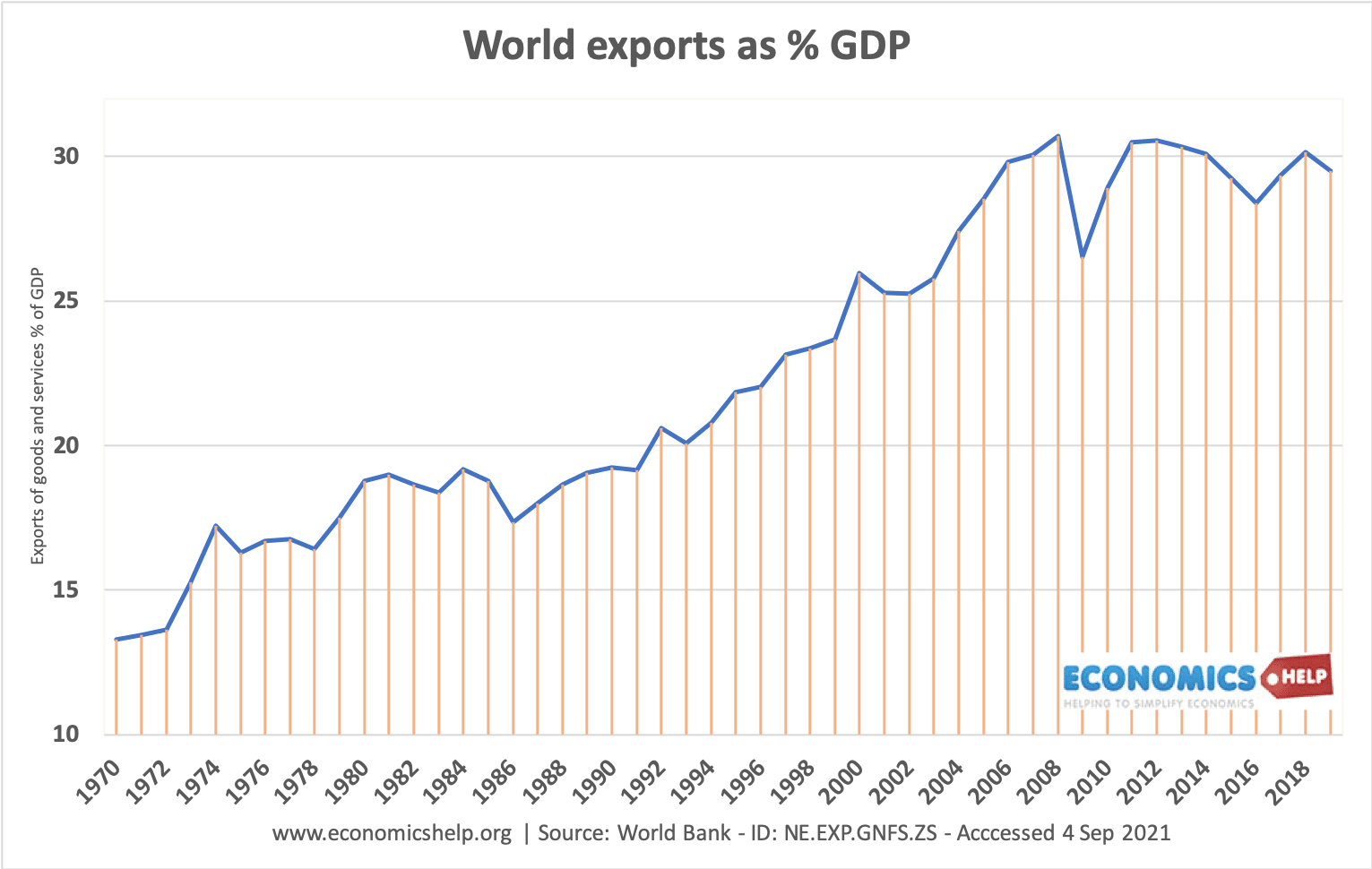

In recent decades globalisation has become so dominant, that we often assume the process is never-ending. Between 1970 and 2008, world exports as a share of GDP rose from 13% to 31%, and it seemed that globalisation was an unstoppable force.

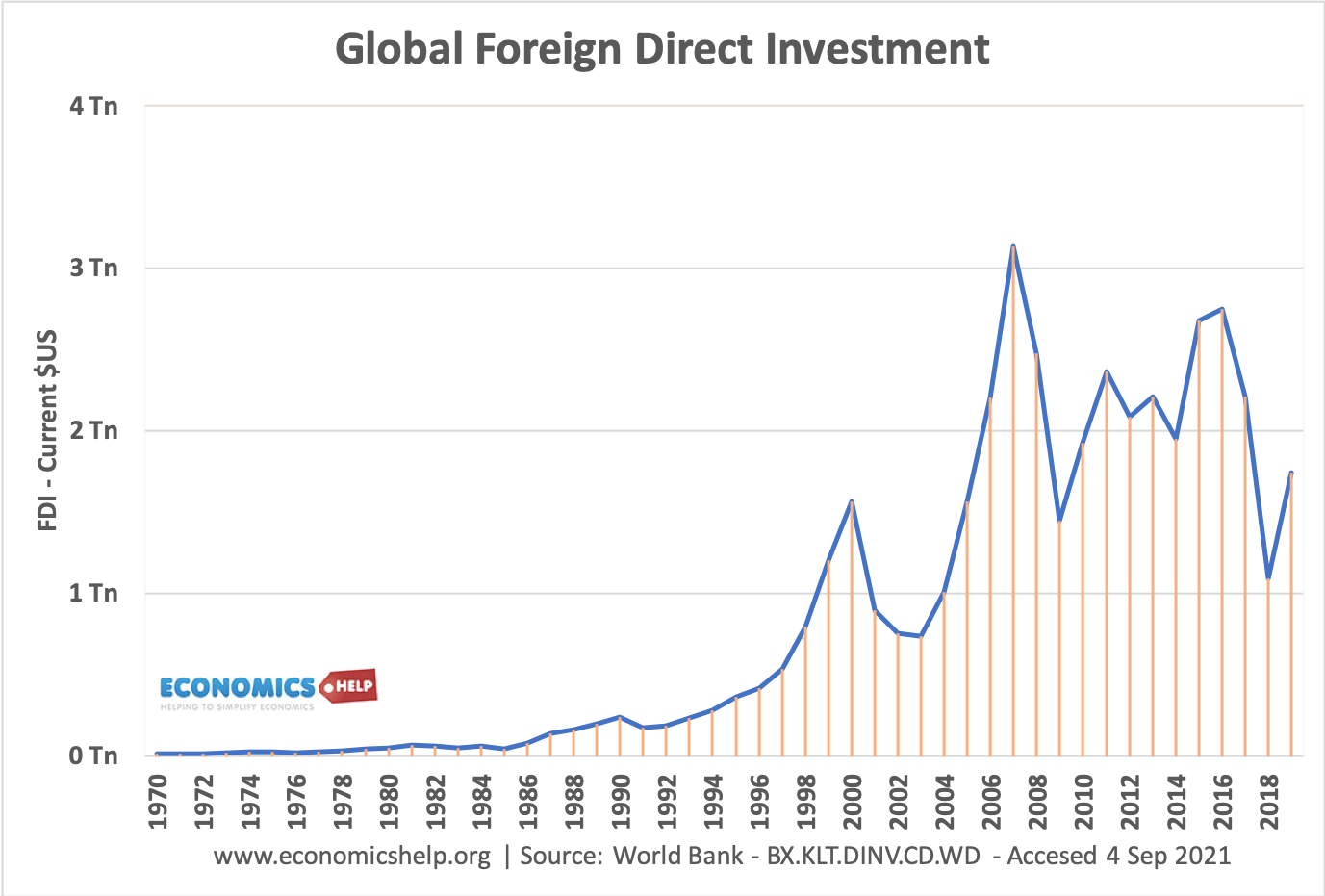

However, since 2008, something unexpected has happened. Exports as a share of GDP has flatlined and even started to fall. Other metrics show a similar fate, a fall in global bank loans, foreign direct investment has fallen quite sharply and multinationals share of profit has decreased.

Covid has further brought into question more aspects of globalisation, such as international travel.

Of course, we still live in a very globalised world, and other metrics such as – internet use, and international phone call measurements, globalisation continues to intensify. But, in terms of trade and the movement of people, we may have reached peak globalisation.

What factors are behind the slowdown in globalisation?

- Gains from lower costs reached. From the 1960s, we saw a very sharp fall in transport costs, due to processes such as containerisation, this made trade much more profitable, but these ‘easy’ gains have been largely exhausted. Now transport faces higher costs from rising fossil fuel prices.

- Improved technology. With labour-intensive industries there is a very clear incentive for firms to move production to countries with significantly lower costs. In the past, manufacturing firms in the US and Europe had a strong incentive to move manufacturing off-shore. However, as manufacturing processes become increasingly automated, labour costs will become a smaller share of total costs. In the future manufacturing will not rely on cheap, plentiful labour, but a more skilled workforce able to manage technology. Therefore the need to ship goods halfway around the world will not be there. Already there are examples of ‘reshoring’ Between 2008 and 2017, US manufacturing has created 16,000 jobs through reshoring. (1)

- Relative decline of manufacturing to services. As incomes rise, we tend to see higher growth for income elastic services rather than goods. For example, as incomes rise we spend more on beauty treatments, going out for restaurant meals and personal services. These services cannot obviously be imported from across the world in the same way goods are. Therefore, more of our income is going on local services compared to international goods.

- Changing consumer preferences. In the past, many manufactured goods were identical. A firm would produce millions of goods on a large scale. However, the modern consumer is increasingly demanding a much more personalised product. Thirty years ago, if you wanted a chair, you would buy what you are given. But, now a consumer can choose between 20-30 variations of colour and features. This means firms have an incentive to move production closer to where consumers live. If you have to wait three months for a shipping container to arrive from Asia, it is too long – consumer preferences may have changed. Successful firms will be based close to their retail market so that the highly individual products can be delivered quickly.

- Higher tariffs. Free trade has created winners and losers. Overall there is a net economic welfare gain, but often the losers have been more visible, creating political pressure. Populists such as Trump have responded by placing higher tariffs on goods – challenging the assumption that tariffs would always fall. It is not just tariffs, but regional blocks are increasingly splintering on issues such as regulation, privacy requirements and tax policy.

- Environmental concerns. In the past decade, environmental concerns such as the global imprint of products have become increasingly important. Consumers are increasingly wary about buying goods, which are imported from the other side of the world, and are willing to pay a premium for goods and food sourced locally. Firms are also responding to this pressure by making some efforts to source locally.

- Carbon taxes. Another factor that may feature in the future is higher taxes on carbon emissions which will increase the costs for airplane use and global shipping. Of course, the industry may find more environmentally friendly methods of transport, but electric engines are harder to use for shipping and planes.

- Multinational firms have found their limits. Multinational firms have often found that global expansion is not without risks. If the multinational doesn’t understand the local market, it can fail to replicate its domestic success. One example, Tesco and Marks and Spencers set up in France but failed to win over the French shopper and they had to retreat.

Globalisation isn’t declining its changing

- Another way of looking at the situation is that globalisation is still occurring but it is changing. Rather than growth through trade of goods, we are seeing a growth in the diffusion of ideas, technology and some services. 10 years ago, if you wanted a print designer, you would find someone local, but now it is just as easy to employ a designer in Brazil or India.

- Covid has led to a slowdown in international travel, but we are still meeting with people around the world through Zoom and Skype.

20 years ago we bought computers, but now we spend more on data storage, apps and pdfs. This data storage and web-traffic is very much a global industry. - Also, whilst trade in goods has flatlined, it is still just under 30% of GDP. Some industries, like car and steel manufacture, have such significant economies of scale, it is hard to envisage anything other than the global supply chains we see now.

Related pages

External links

- The steam has gone out of globalisation – Economist (2019)