For many people, especially those under 40, the UK housing market appears broken, with excessive prices making it difficult to buy and very expensive to rent. Housing costs are one the biggest factors in a long-term cost of living crisis. The UK isn’t alone, with many advanced economies also facing a broken housing market and the risk of big house price falls soon. Why did house prices become so expensive and what are the problems of this?

Lack of housing supply

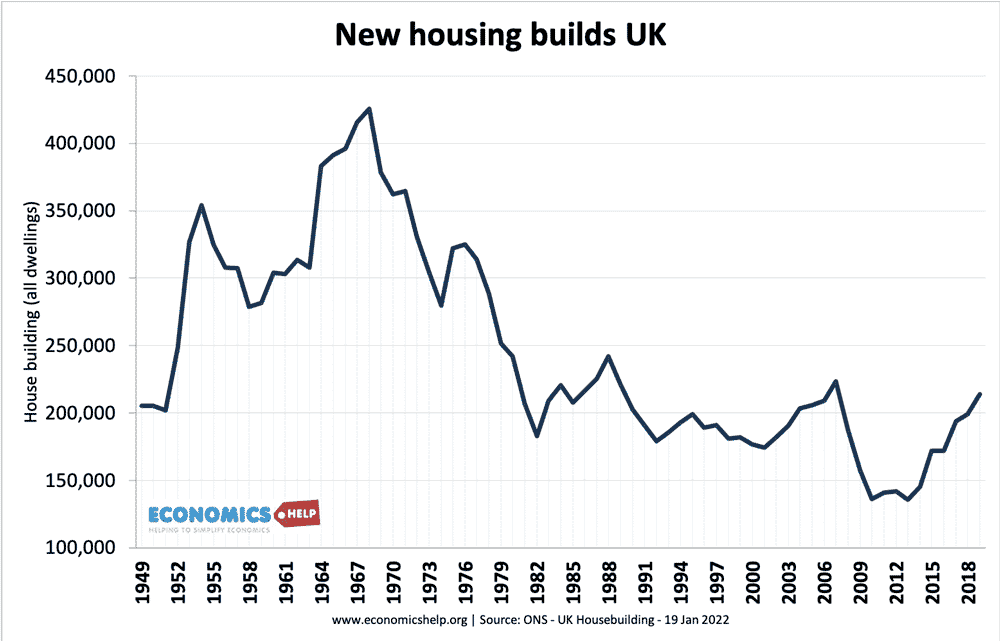

Source: House building ONS July 2022

In the long-term, the fundamental problem is that it has proved difficult to build sufficient housing to meet rising demand. Since the 1980s, new home builds have been consistently below the government’s target. There are several reasons for the lack of home building.

The most significant is the strong local opposition to the building of new homes. Generally, people agree more homes need to be built, but there is a real NIMBY problem. We want them built elsewhere. Politicians on a national level know the need to build housing and often make optimistic promises, but on a local level, there is political opposition to widespread home building and so it proves difficult to keep up with demand.

In the UK, planning regulations definitely make it harder to build homes and empower local communities to hold up many projects. The issue has been made more challenging because there has been a flight from densely populated housing in inner cities to the suburbs, where there is more pressure put on greenbelt land.

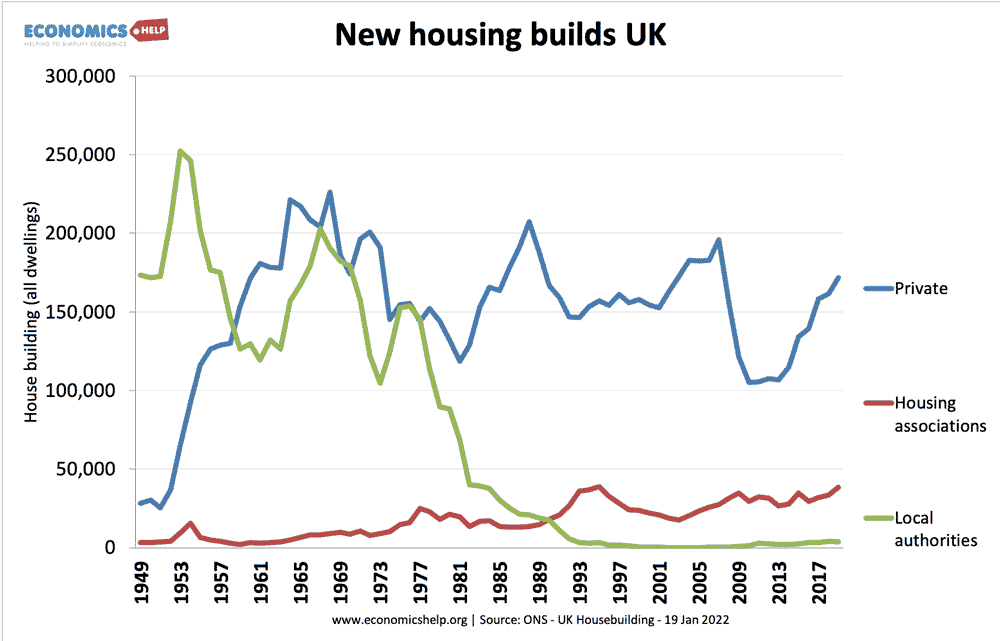

A decline of council housing. In the aftermath of the Second World War, Britain had an acute housing shortage, but in the 1950s made strenuous efforts to build housing, including a large of number of council housing. These good-quality houses were then rented at low rates to the working population. However, in the 1980s, a big change of policy saw the government cut funding for building council houses. Also, council housing was sold off, under a ‘right to buy’. It was very popular with council tenants who were able to buy a property cheaply, but the long-term costs is a lack of affordable council housing and extremely long waiting lists. In many cases, councils have had to rent the property back from landlords to provide accommodation for the homeless. There are now 1.4 million fewer households living in social housing in England alone than there were 40 years ago. (link)

The post-war saw large numbers of housing built by local authorities, this fell in the 1980s and never really recovered. It was a policy decision to rely on the free market to build houses and provide little public funding for the building of new houses.

Increased demand

The difficulty in building houses has been exacerbated by a substantial rise in demand. The increased demand for housing has occurred for a few reasons related to population growth, declining household size, net migration and growth in second homes.

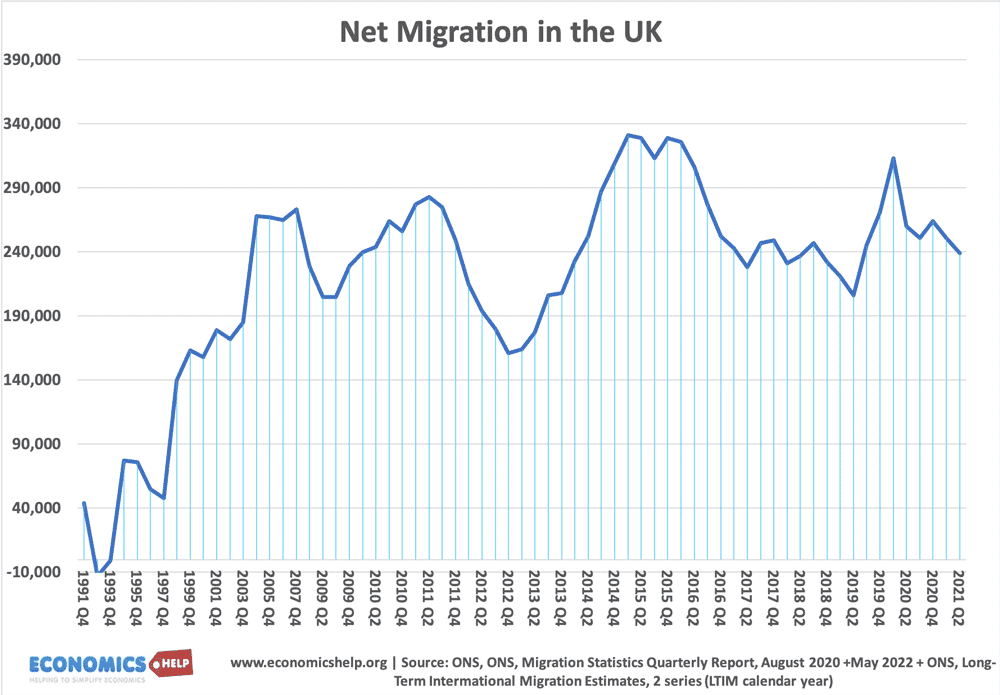

Net migration

Since the early 1990s, net migration has averaged over 200,000 accounting for roughly 50% of the UK’s population growth. Even Brexit has not reduced net migration because EU migration has been replaced with non-EU migration.

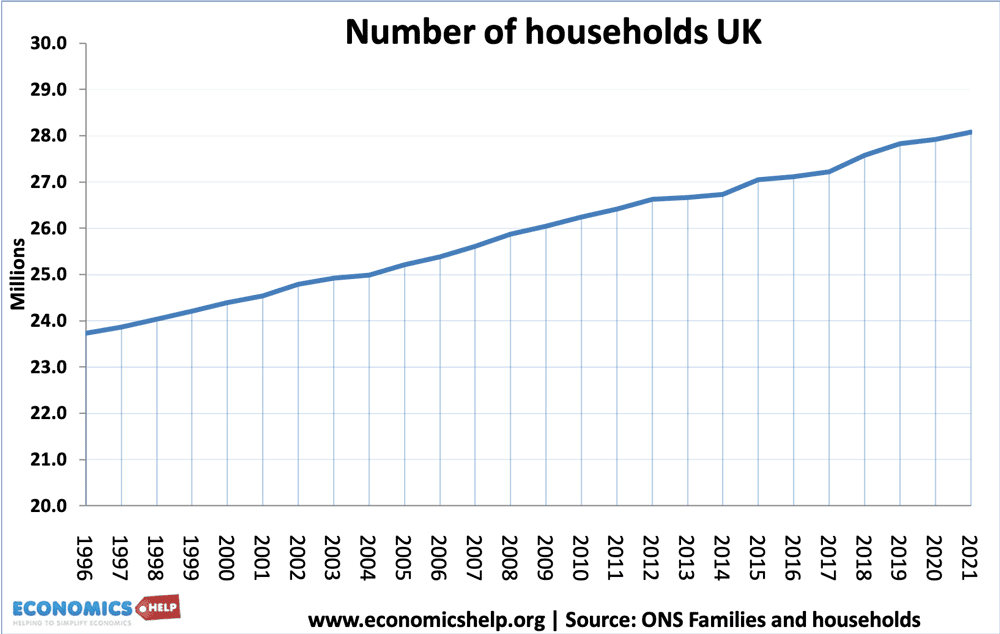

Rising number of households

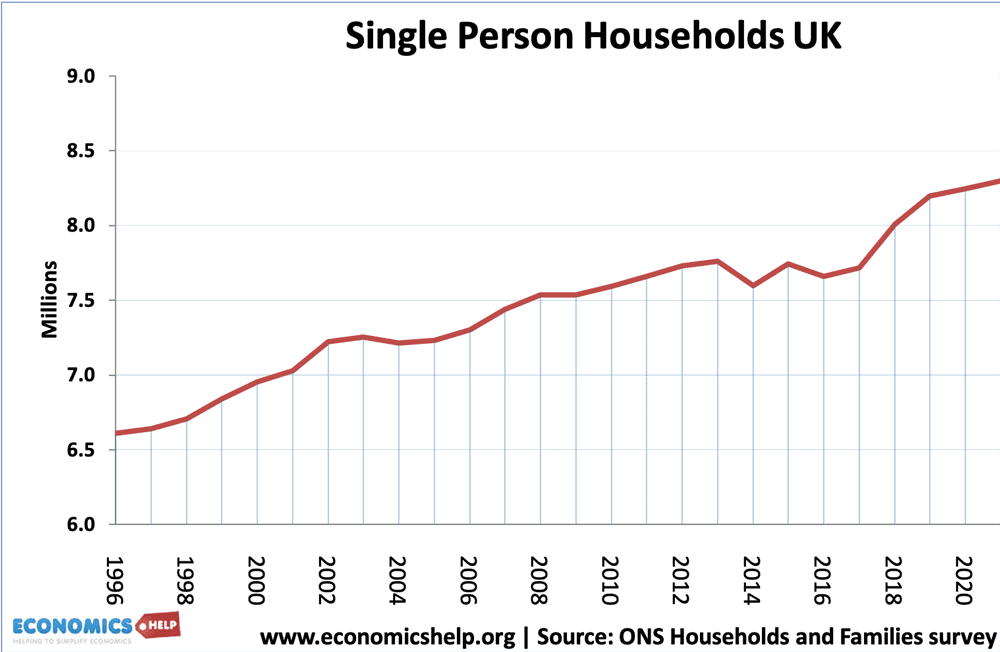

The ONS state there were an estimated 28.1 million households in the UK in 2021, an increase of 6.3% over the last 10 years and a 16% increase since 1996.

One driving force behind the rise in the number of households is a rise in the number of people living alone – usually old, people who have divorced, separated or outlived their partner.

There has been a decline in the size of the average household with rapid growth in one-person households.

However, the housing crisis itself has started to reverse some household trends. The number of young people living with their parents has increased significantly. The number of young adults living with their parents has grown by over 1.1 million since 1996, reaching a peak in 2020 of 3.5 million. (ONS) In 2020, 47% of males and 36% of females aged 15-34 lived with their parents, an increase of 15% since 1996. (record rise)

Rise in buy to let

A period of ultra low interest rates have increased the attractiveness of investors buying houses to let. Property has become one of the best forms of investment, especially in major cities and tourist areas, where AirBNB has created a new market for housing. The English Housing Survey estimates that English households owned 873,000 second homes, of which 495,000 were second homes located in the UK. (Parliament)

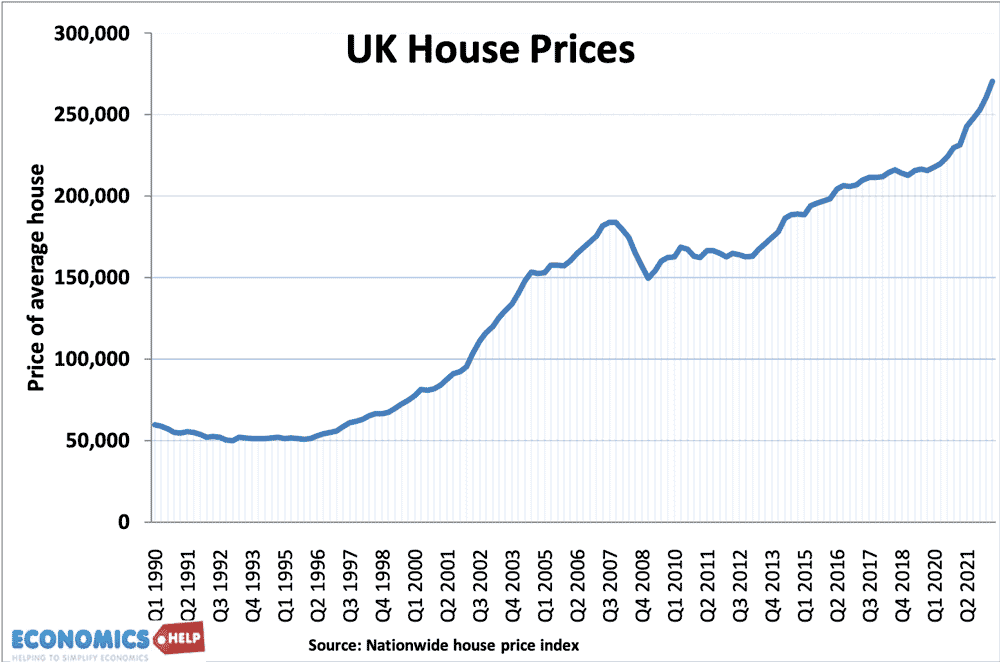

Incomes fallen behind house prices

According to the IFS since 1997 property prices have increased by over 173% in England whereas real incomes for 25-35 year olds have increased by just 19%. The last 20 years have seen a substantial fall in homeownership among young adults. In 2017, 35% of 25- to 34-year-olds were homeowners, down from 55% in 1997.

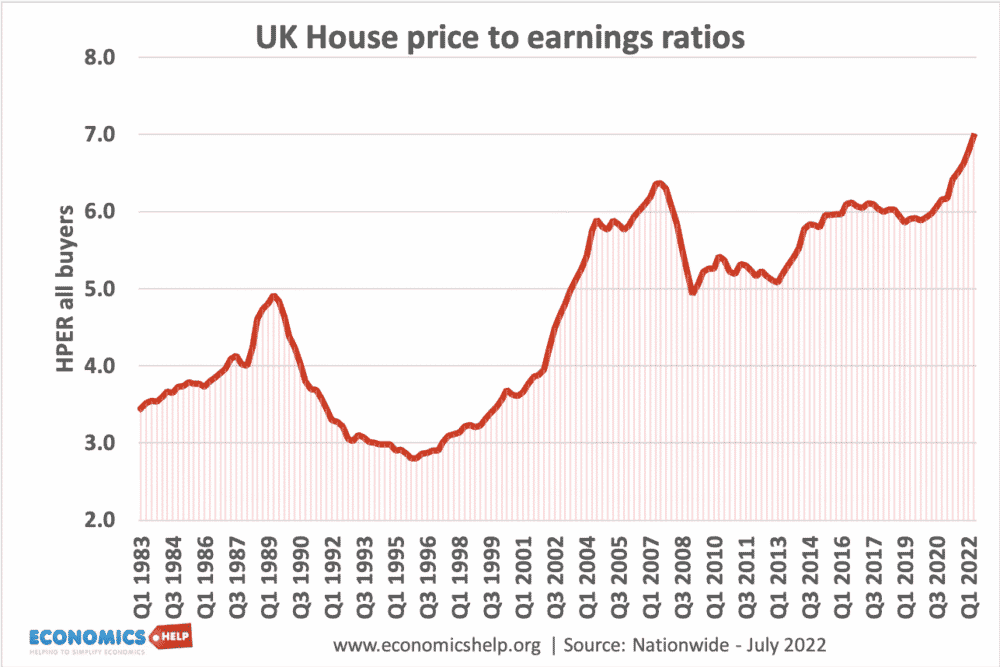

The result is that the ratio of house price to earning ratios are at a record high in 2022. According to the ONS, in 2021 median household income in the UK was Median household disposable income in the UK was £31,400. With lenders rarely lending out more than four times multiple salaries, there are few properties within reach. (4 * £31,400 = £125,600.)

In 2022, average house prices are £281,161.

Help to buy. Given the difficulty of buying homes, one government policy was to give help to young people to borrow more. Help to buy gave first time buyers the option to an extra government backed equity loan of up to 20% of the new home build. However, this policy only masks the real issue and further inflates prices rather than tackle the fundamental disequilibrium.

Wealth inequality and intergenerational lending. Another factor that has kept house prices artificially high is that some parents with spare equity have helped their children buy house by offering deposit or part funding. Despite incomes appearing to be insufficient to buy houses, demand has been maintained by this intergenerational lending. A drawback is that this has increased inequality between those who can borrow from parents and those who can’t. According to Zoopla

“Nearly two-thirds of parents have helped their children with a deposit for a new home, forking out an average of £32,440.”

Problems of expensive house prices

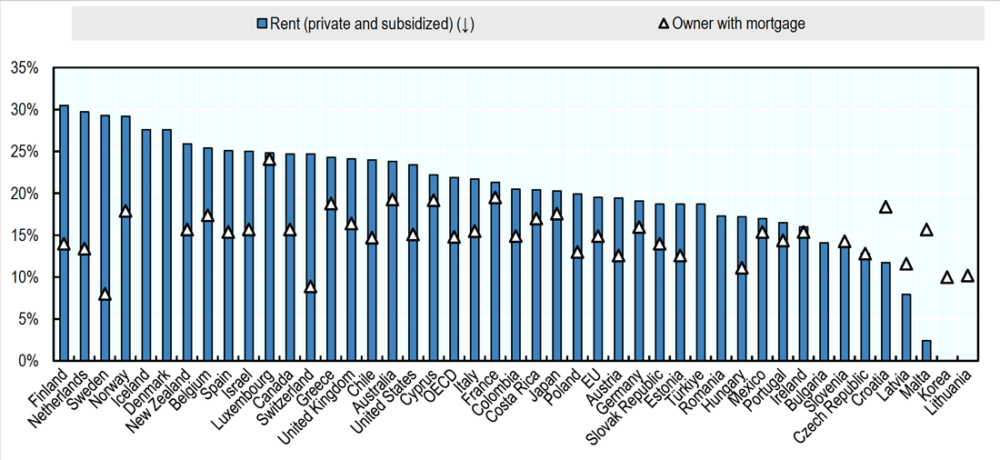

1. Inequality. Housing is a major source of expenditure. With people in the lowest income decile who privately rent tending to spend the highest share of income on housing costs.

Future costs of housing crisis. There are also concerns that the current generation rent, will face poverty in old age, where a generation of retired workers will need to continue paying expensive rents, rather than benefitting from having paid off a mortgage and living rent free in retirement. The importance of housing costs distorts actual living standards.

2. Geographical immobility. The housing market creates problems for the economy as a whole. The difficulty of renting or buying has a direct impact on difficulty filling labour shortages. In particular areas such as London, with the worst housing crisis often have difficulty filling public sector jobs, such as nursing and teaching. It can worsen geographical unemployment, with the unemployed in depressed areas hampered by difficulty of finding accommodation in booming areas.

3. Homelessness. Shelter report that 274,000 people are homeless in England, including 126,000 children of these roughly 2,700 people are sleeping rough. Whilst there are many reasons for homelessness, the shortage and expense of housing is a major contributory factor and the decline of available council housing, exacerbating the problem.

The volatility of house prices

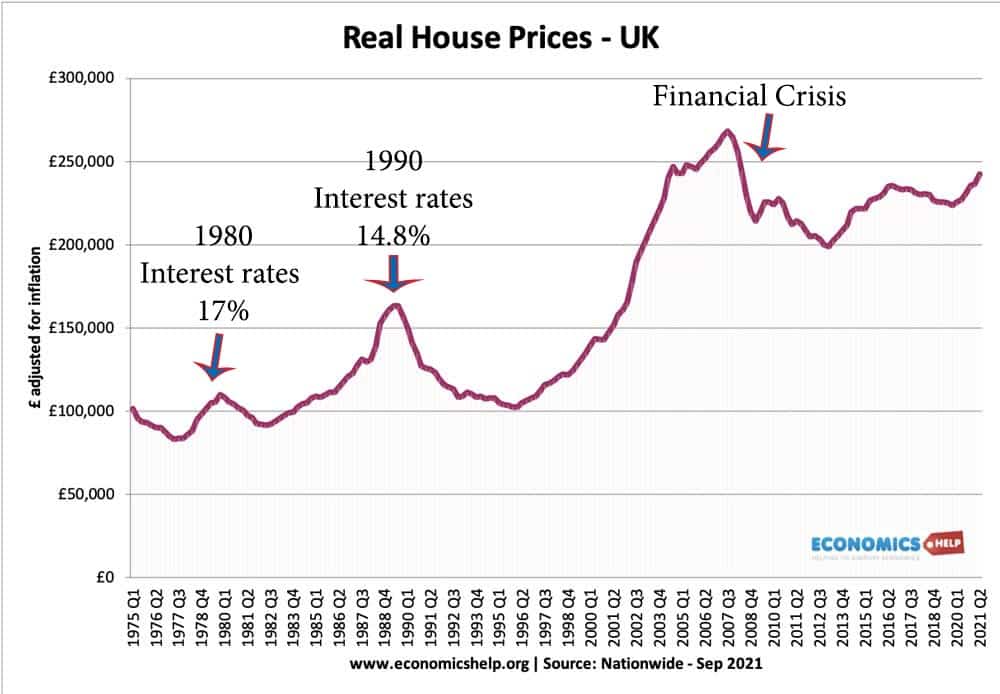

Although house prices are exceptionally high, there are not immune from house price falls which can leave people with negative equity. In particular, when interest rates rise, there is a strong pattern of falling prices. For example, in the early 80s, 90s. The financial crisis of 2007 was different in that interest rates did not rise, but there was the whole issue of bad bank loans and people getting carried away by rising house prices.