Since privatisation in 1989, water bills have risen 40% and the industry is profitable for shareholders. Yet are households getting benefits? In recent years, we have seen a surge in the discharge of raw sewage, hosepipe bans and a lack of investment. OFWAT, the water regulator recently stated.

“For some companies, poor performance has become the norm. This cannot go on,”

Despite the many problems in the industry, water companies have been able to pay themselves £72bn in dividends since privatisation. A utility once run in the public interest, is now run for the benefit of private companies. Even the market friendly Financial Times recently stated.

“water privatisation looks like little more than an organised rip-off”

What is the logic of privatisation, what has gone wrong and can anything be done to fix it?

In 1989, the water industry was publically owned and the creaking infrastructure needed significant investment to improve water standards. During the 1980s, the amount the water industry was able to invest was capped at £2 billion a year. But, in the late 1980s European directives on water quality meant the UK would need to significantly improve water infrastructure. Rather than invest public money, Mrs Thatcher sold the whole industry to the private sector. The privatisation raised £7.5 billion.

The arguments for Privatisation were

- The private sector would be more efficient and make better use of investment funds.

- The private sector would not be held back by government limits on investment levels.

- The government would raise a one off lump sum for selling the infrastructure.

- The water regulator, OFWAT would prevent the new private monopolies from abusing their market power.

Privatisation

In the first five years of privatisation, bills rose rapidly. But, rather than use this increase in prices, water companies borrowed to finance investment. Higher profits have led to higher dividends. For example in 10 years from 2007-2017, profits of £18.8bn led to dividend payments of £18.1. (FT)

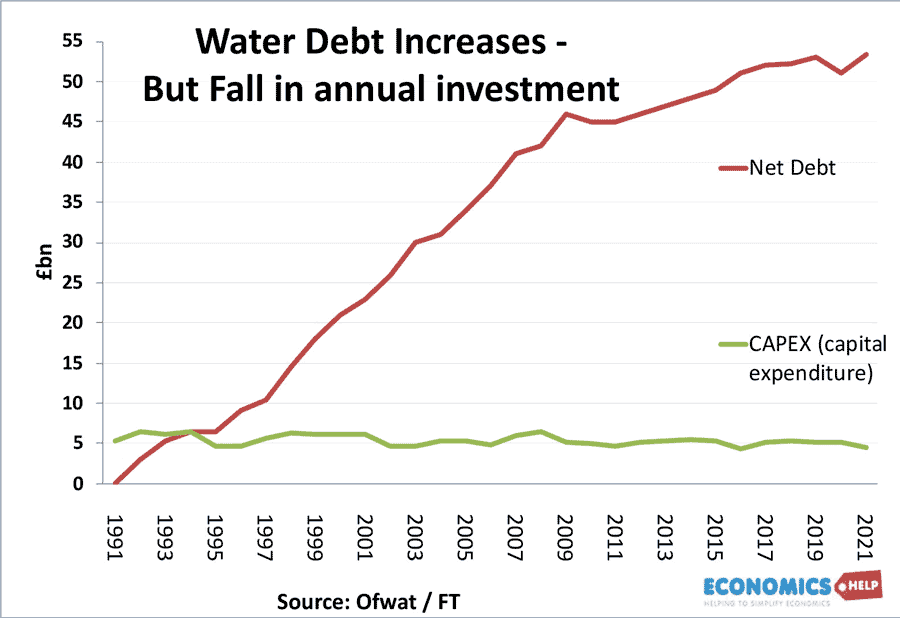

Since privatisation, the FT point to a total of £72bn dividend payments whilst debt has risen to £54bn. This £54bn of debt has led to higher debt interest payments which push up bills. David Hall a professor at the University of Greenwich reports last year the annual cost of dividends and debt payments was £2.3 billion.

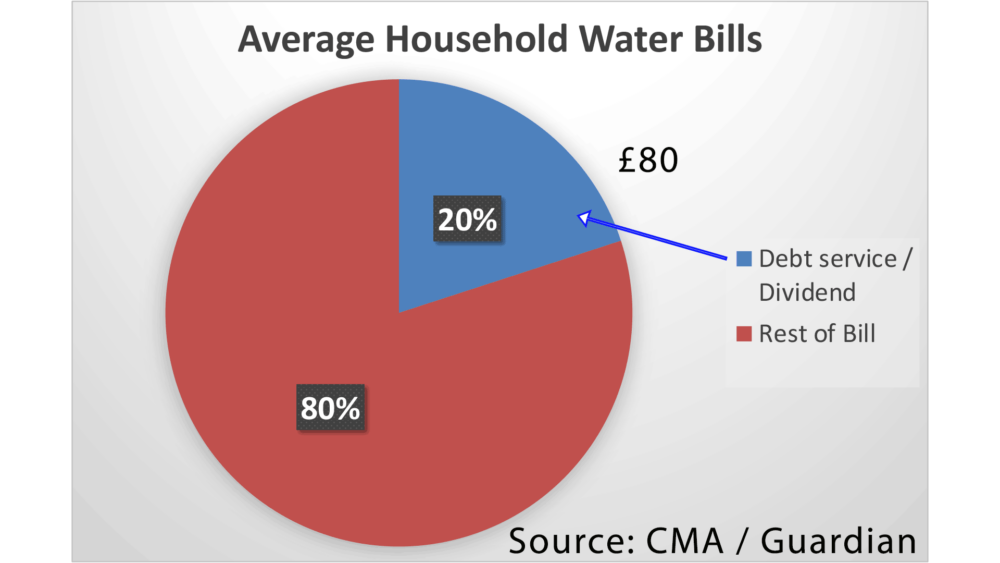

The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) estimate customers are paying £80 or 20% of their water bill towards servicing debt and rewarding shareholders. This is a cost of privatisation. And as interest rates rise rapidly, this interest cost is rising and even threatens the financial viability of the heavily indebted companies.

It is sometimes assumed that the private sector is more efficient than the public sector. It is taught as an almost universal law in economics. But governments can borrow more cheaply than the private sector. Privatisation has led to a rise in debt of water companies, and households pay towards the cost of servicing it.

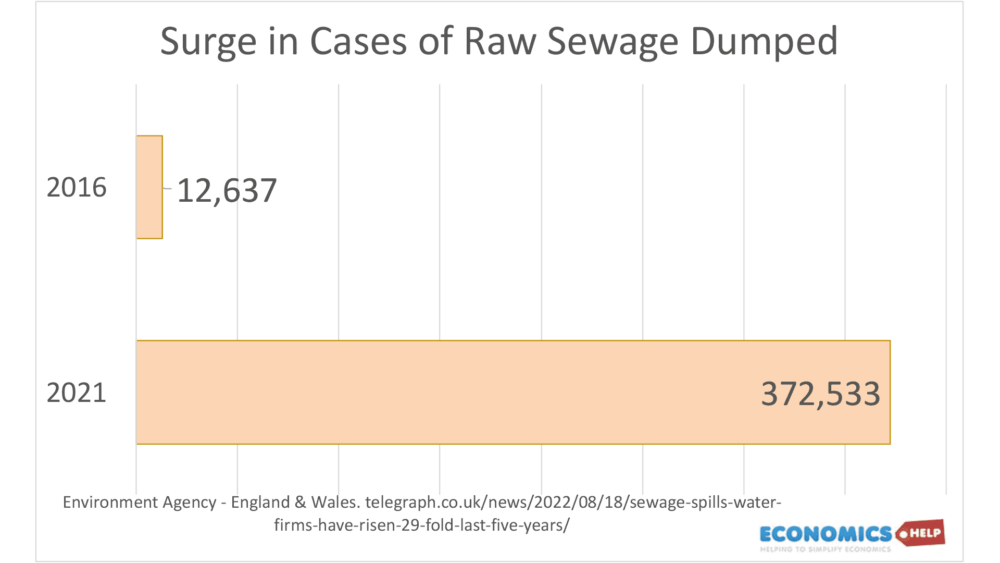

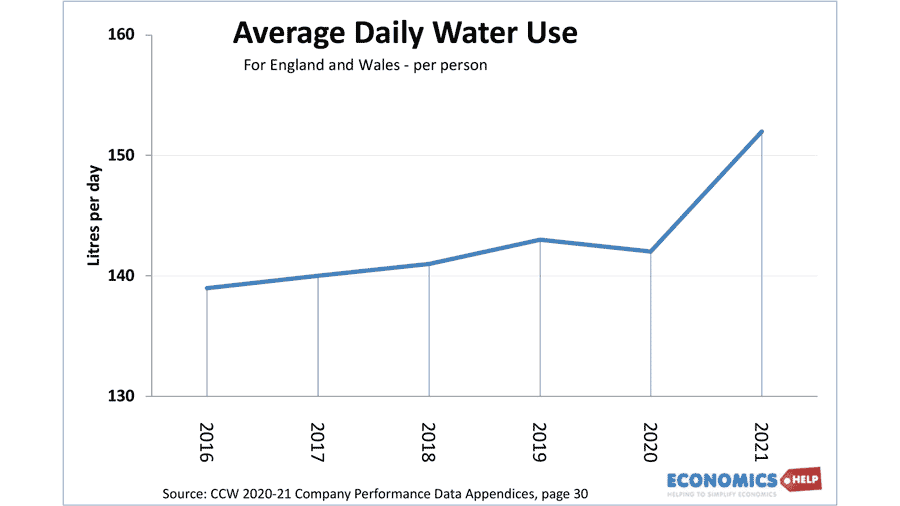

In theory, a profit motive can increase efficiency, but in a public utility like water the profit motive is more dubious. In a public utility like water the easiest path to higher profits is to under-invest, put up bills and discharge sewage into rivers rather than treat it. And this discharge of waste has become a very visible problem for many who live near rivers and seas. According to the Environment Agency, incidents of discharging raw sewage has risen from 12,637 in 2016 to 372,533 last year a 29 fold increase. This increase is primarily because of an increase in the number of monitoring of sewage systems, which is hoping to provide better data for the scope of the problem.

There have been occasions when water companies find it more profitable to pay relatively small fines than avoid dumping. This is a classic example of a negative externality with the environment and people suffering the effects of polluted rivers and beaches.

Companies have often sought to hide their own pollution. Only 77% of recorded incidents are self-reported, leaving it to the environment agency and local pressure groups to raise awareness of pollution.

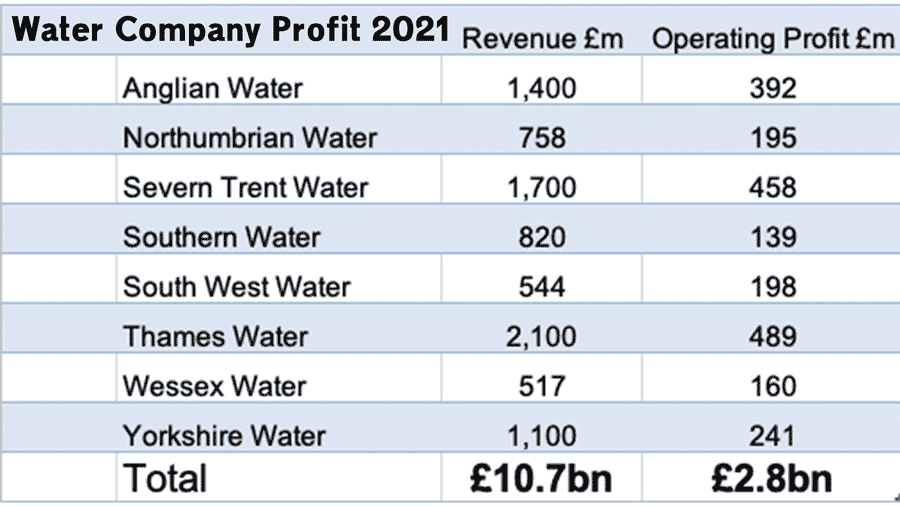

Despite water companies being fined for pollution and missing targets, in 2021 they received 20% higher bonuses. In total, the 22 water bosses paid themselves £24.8m over half in bonuses in 2021-2022.

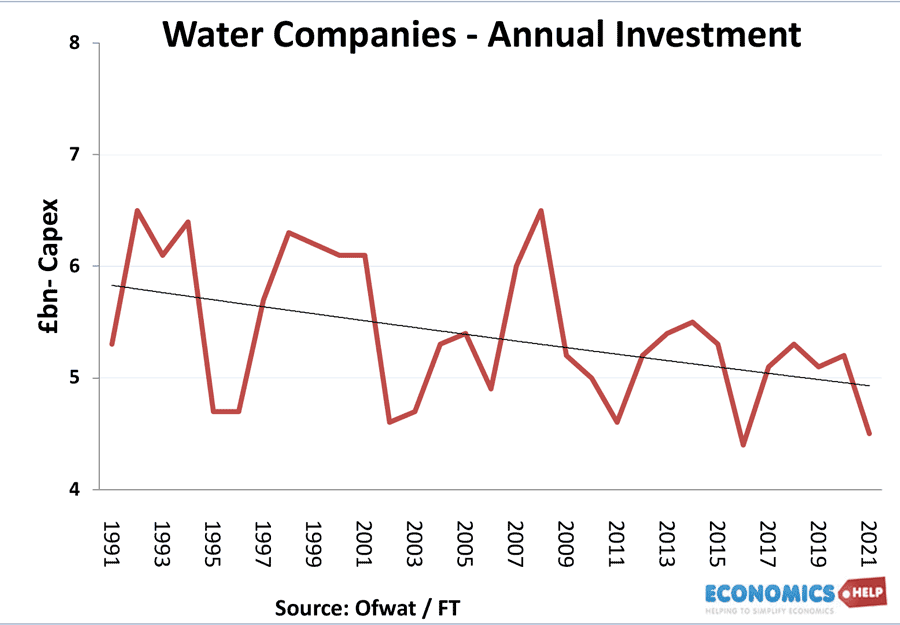

It is important to stress, there has been significant investment by water companies since privatisation – a total of £123bn – although annual investment has fallen in recent years. They can also point to improvements in some service criteria. The National Audit Office state between 1990 to 2010 rates of low water pressure fell from 1.3% to 0.01%. Unplanned supply interruptions of more than 12 hours fell from 0.33% to 0.06%.

However, there is a strong perception that privatisation has given a raw deal to the consumers and the environment. According to researchers at Greenwich University – between 2002-18, Scottish water, which stayed in public hands, have kept real prices stable, whilst prices in England rose 15%. And during the same period, Scottish Water invested 35% more per household than English water companies.

England and Wales is pretty much alone in the world to privatise the whole water infrastructure. Water is an essential public service where the profit motive of companies is not helpful.

France tried partial privatisation but has since allowed private licenses to lapse and bring the system back into public ownership.

By contrast, the English water system is increasingly owned by a complex network of foreign companies, with companies often registered in countries like the Channel Islands to pay lower tax. The FT reports that in a ten year review of water company accounts, that on profits of £20.7 bn they only paid an average tax rate of 8% or £1.7bn.

Because there is no competition in water, it still requires quasi government intervention. With a government body OFWAT responsible for setting prices, investment levels. Yet, in 2016, the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee found OFWAT were too generous and “As a result, water companies made windfall gains of at least £1.2 billion between 2010 and 2015 from bills being higher than necessary.”

The reason British water companies are attractive to foreign investors is the very good rates of return. The FT report for example, Macquarie received returns of between 15.9 per cent and 19 per cent during the 11 years it controlled Thames Water, double the usual average for utilities.

In a recent review of water industry, OFWAT admitted that apart from one success in reducing water leakages to lowest levels since privatisation the state of the industry was dire with unfolding scandals about sewage discharge and underinvestment despite rising dividends. Whilst OFWAT admit, poor performance has become the norm, it also seems OFWAT is too weak to deal with the water companies. They have been powerless to prevent rising debt or the payment of dividends whilst investment is underfunded. Naming and shaming firms who pollute rivers hasn’t really altered behaviour.

This is a problem of water privatisation, it still needs very strong government intervention to make private companies behave in the public interest. Which raises the question – what is the point of privatisation?

It is true that nationalisation is no panacea. Under public control, in the 1980s the water industry was starved of necessary investment by Central Govermment (pre 1989, investment was capped at £2bn per year). Fixing Victorian sewers and dealing with climate change is a big task, but, it is hard to see what the consumer has gained from privatisation.

Paying higher prices to enable the payment of dividends to foreign shareholders is galling, when you read about your local rivers polluted with waste water and hosepipe bans because no new reservoirs built in past 30 years. If water was publically owned, at least you know higher prices would go to the public purse rather than foreign shareholders.

Water privatisation stems from an ideological belief in the superiority of the private sector, but it would have been much cheaper for government investment in the industry rather than private investment which requires higher interest rates, plus dividend payments.

There is a lot of literature on the efficiency of private vs public ownership. Many studies show it is difficult to find any strong relationship either way.

“For utilities, it seems that in general ownership often does not matter as much as sometimes argued. Most cross-country papers on utilities find no statistically significant difference in efficiency scores between public and private providers.”

“there is no hard evidence which points to a causal relation between management ownership and efficiency”.

González-Gómez, Francisco, and Miguel A. García-Rubio. 2008. ‘Efficiency in the Management of Urban Water Services. What Have We Learned after Four Decades of Research’. Hacienda Pública Española/Revista de de Economía Pública 185 (2): 39–67.

“after privatization, productivity growth did not improve … average efficiency levels were actually moderately lower in 2000 than they had been at privatization [in 1989].”59

Saal D., Parker D., and Weyman-Jones T. (2007) Determining the contribution of technical change, efficiency change and scale change to productivity growth in the privatized English and Welsh water and sewerage industry: 1985–2000. J Prod Anal (2007) 28:127–139 DOI 10.1007/s11123-007-0040-z

So we have all the drawbacks of privatisation without any of the benefits. It seems the average householder is getting the worst of high bills, poor service and disregard for the environment. With global warming causing extreme weather, there is likely to be increasing pressure on water infrastructure in the coming years, but the system of private ownership and weak government regulation seems poorly equipped to deal with the challenges of the coming years.

Further reading