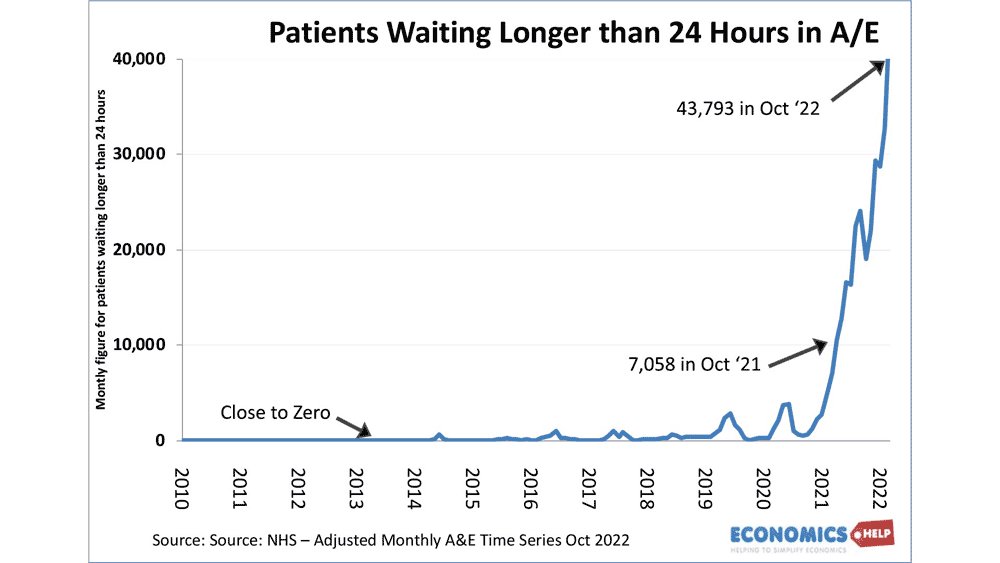

Last week I accompanied a friend with a broken arm to a local hospital. We arrived 8 pm, but we didn’t get seen until 5 am. This kind of experience is typical of the recent surge in waiting lists that we have seen in the NHS.

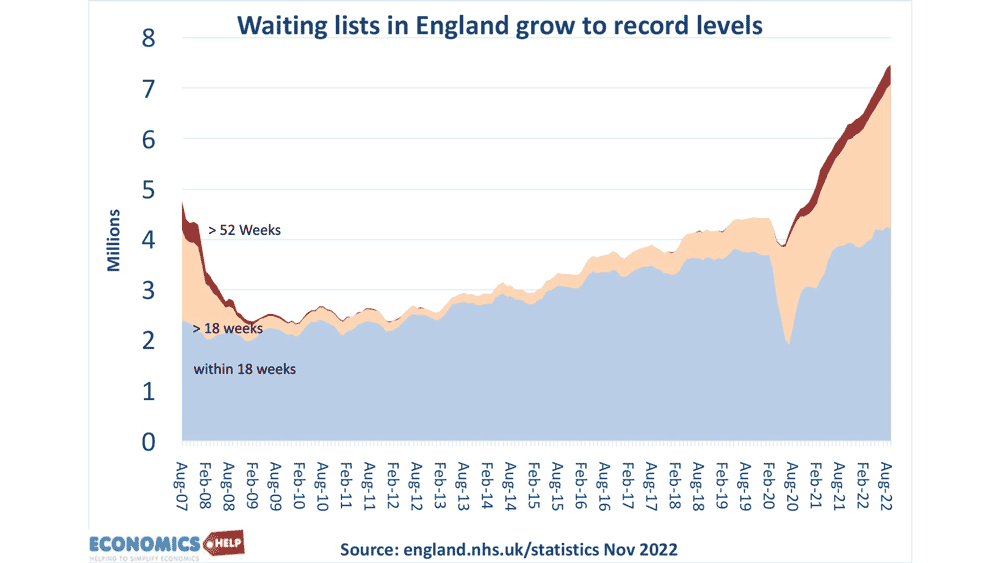

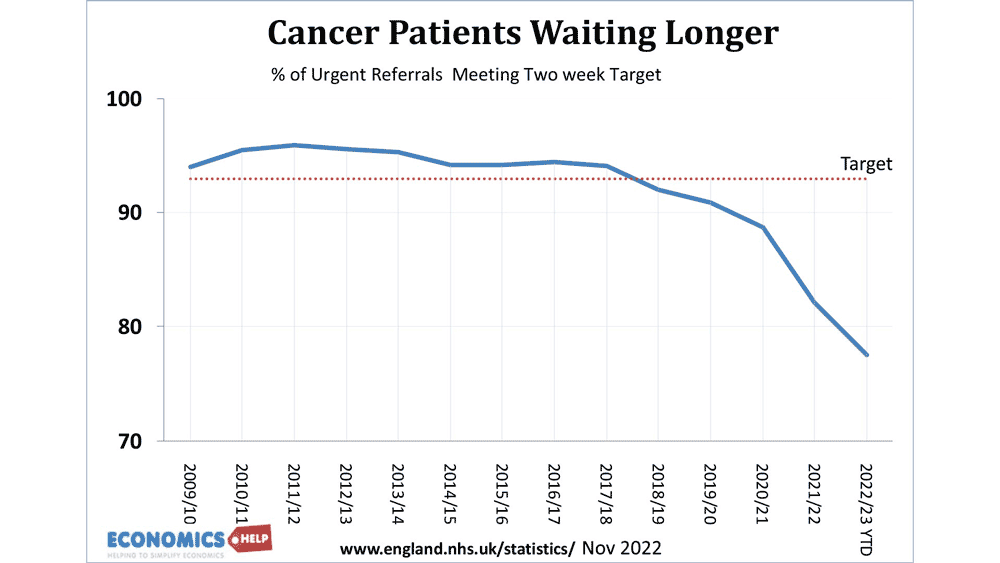

We can see it in waiting lists for A&E, ambulance waiting times, cancer treatments and general waiting lists.

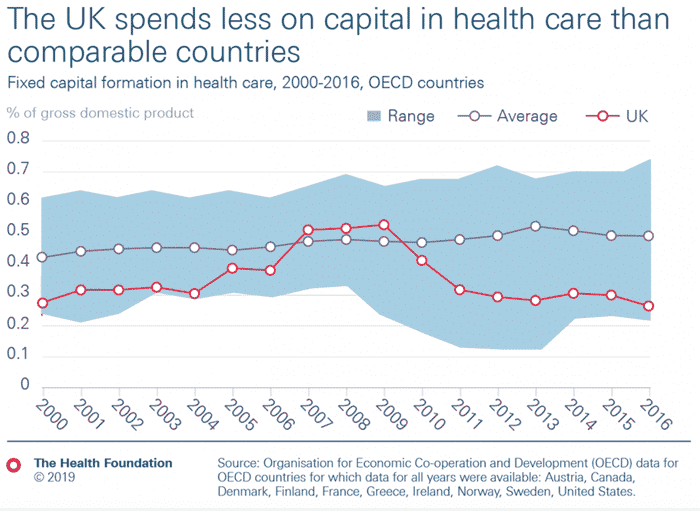

One of the biggest problems in the NHS is the lack of capital spending. The UK has one of the lowest ratios of health capital spending in the OECD.

This is the long-term investment in building new hospitals, increasing beds and also improved technology to aid doctors and nurses. Capital investment does not give immediate headline returns, but years of under-investment mean the system lacks capacity – and when Covid struck, there was no spare capacity to absorb the surge in demand.

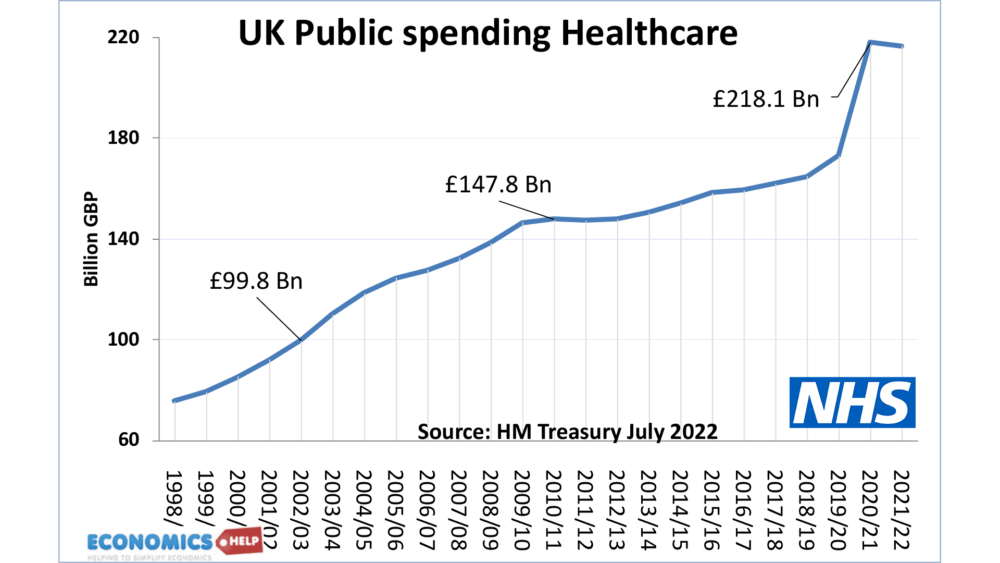

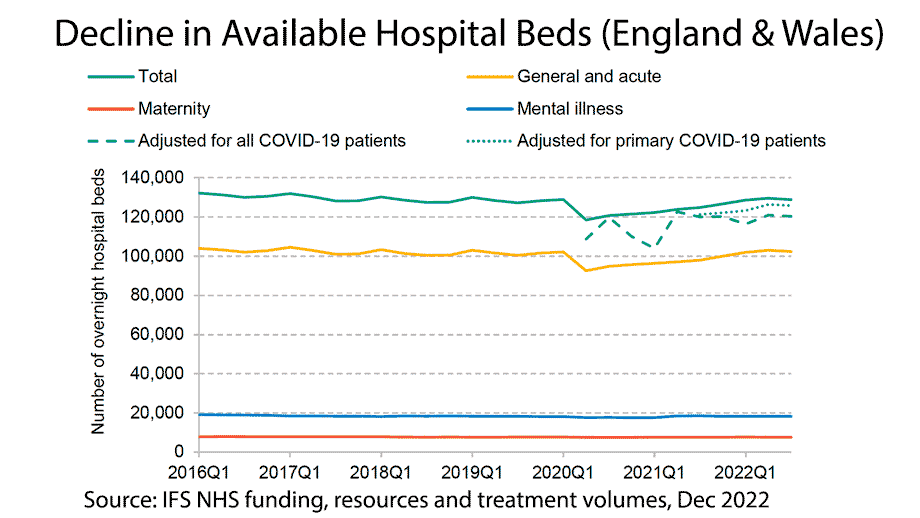

To deal with Covid, since 2019, there has been an increase in real healthcare spending and an increase in the number of doctors and nurses, but their productivity has fallen. There has been a decline in the average number of treatments per doctor/nurse. It is a result of having to juggle a system at breaking point. For example, there is a continual struggle to find beds for patients. The IFS report that since 2016, there has been a decline in available hospital beds – despite a sharp rise in demand and a growing population. Adjusted for Covid, the decline in hospital beds is even more acute.

Given the record low levels of bed vacancies, doctors and administrators waste time juggling the acute shortages making it difficult to concentrate on patient treatment. It is not just the frontline NHS but also the state of social care. Hospital beds are taken by patients who could go home, but with inadequate social care, beds get taken by long-term patients. The FT also report issues with administration and knowing where available beds are.

To fix waiting lists does not just require more consultants and nurses, it also requires more hospital beds, and equipment to be able to deal with the backlog. The government have promised to build 40 new hospitals before 2030, but this has been a contentious claim with

According to Full Fact, mentioning this includes only 3 completely new hospitals, with the rest being rebuilds or new wings added to existing hospitals. It is also uncertain whether these projects will be completed on time

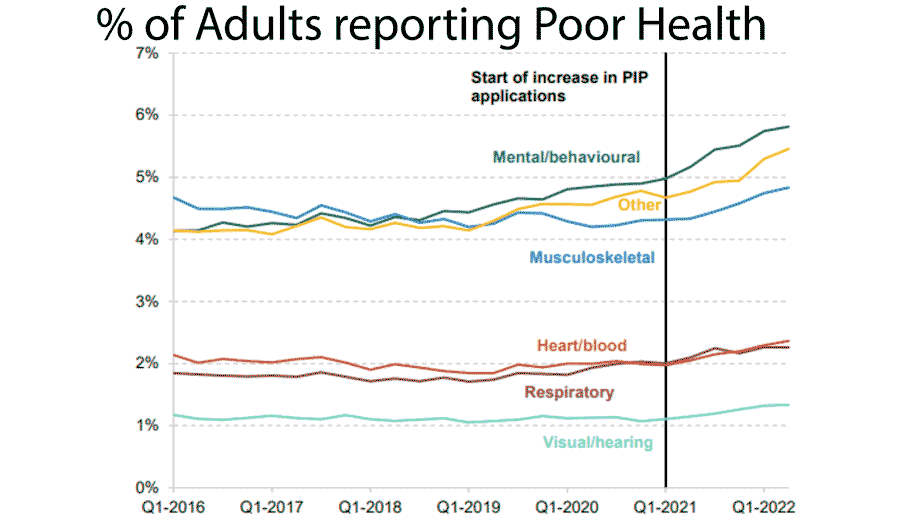

Another major problem for healthcare in the UK is that since 2019, the health of the population has deteriorated. This includes the long-term problems of Covid. Although not so newsworthy, average hospital admissions for covid are higher in 2022 than in 2021. However, it is not just Covid, many other health conditions have worsened since 2019, such as heart disease, mental stress, and respiratory problems. It has led to a rise in the number receiving long-term sickness benefits.

This has numerous effects on the health system. Firstly, there is the obvious pressure on hospital beds, waiting lists and doctors. Secondly, it has affected the health of healthcare professionals, meaning the NHS has to deal with more labour shortages. Whether this is a permanent decline in health or temporary remains to be seen.

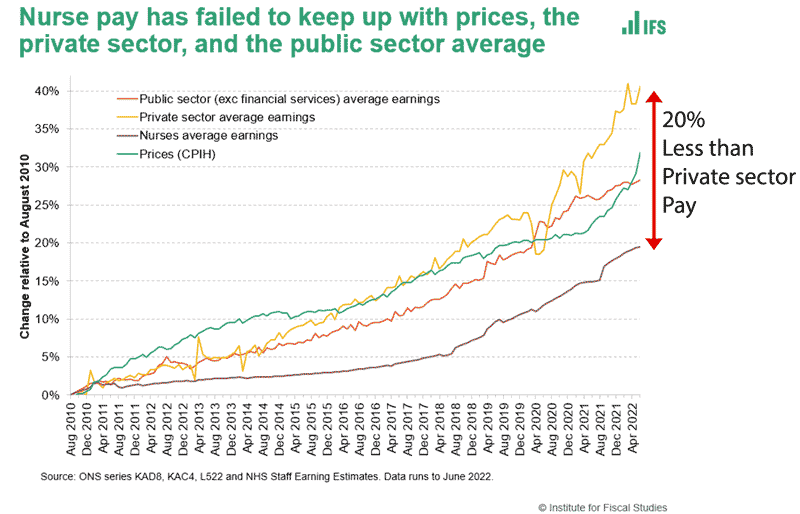

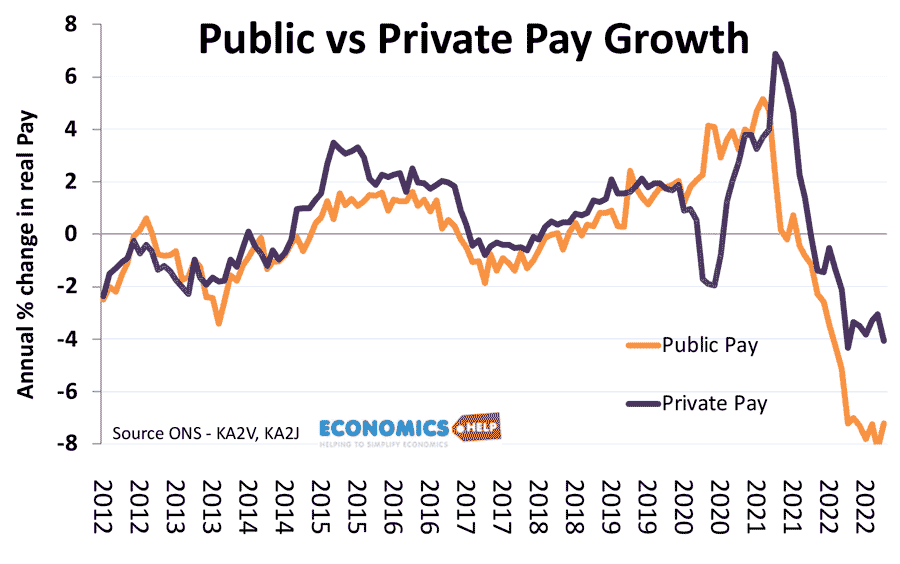

Another part of the healthcare crisis is the pressure put on doctors and nurses. Covid stretched many to work very long hours in very difficult conditions. However, since 2010, there has been a sharp decline in the real pay of doctors and nurses. Nurses’ real pay has grown 20% less than private sector pay and 10% lower than inflation – an unprecedented decline in real pay.

Although real wages have been falling rapidly in recent months, you can see a much sharper decline in public sector pay. This has particularly affected nurses, doctors and consultants. Nurses’ pay is now relatively low compared to other countries Given the pressures of working in the NHS, the decline in real pay is making it harder for the NHS to fill vacancies with many leaving the profession from ill health or burnout.

The government claim that to increase public sector pay in line with inflation would cost £28bn but this is misleading because, according to ITV News, they are assuming two years of 11% wage growth and they already included 5% wage growth into the budget. The cost of meeting the nurses demands for 19% would likely be in the region of £2-3 billion. If all public sector workers were given wage rises to match CPI inflation, the cost would be in the region of £10-15 billion.

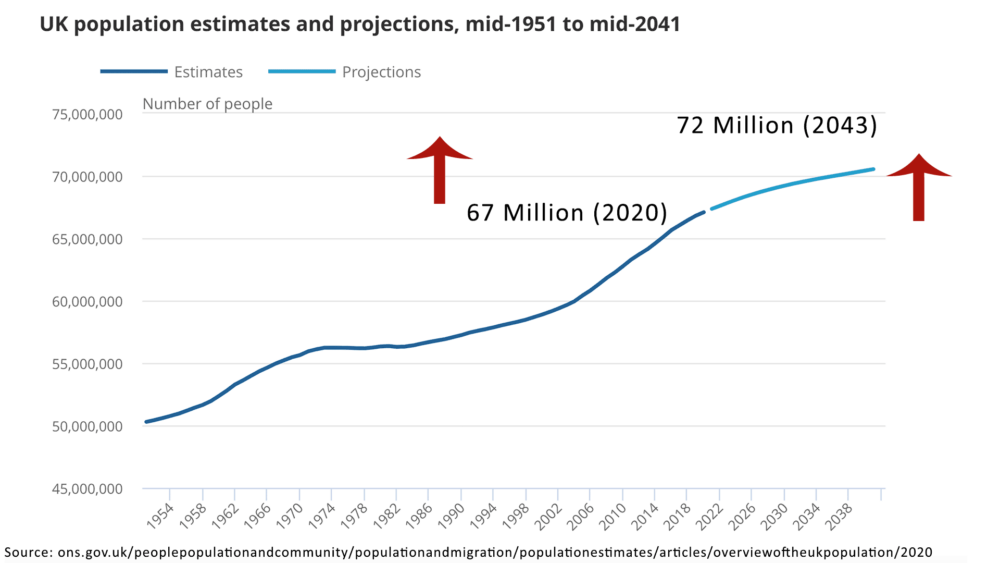

Another long-term issues for the NHS is a rise in the population, combined with an ageing population, this means that rise in real spending is not necessarily enough, given the bigger rise in demand from a growing old population.

Also, worth mentioning there is a strong macroeconomic case to see health care spending as public investment which can improve not just health but labour productivity. The UK’s long-term decline in productivity and economic growth, is at least partly caused by ill health and decline in labour participation. Whilst there is no short-term solution to fixing the nations health, but it would provide not just personal benefit but an economic windfall too.

Related