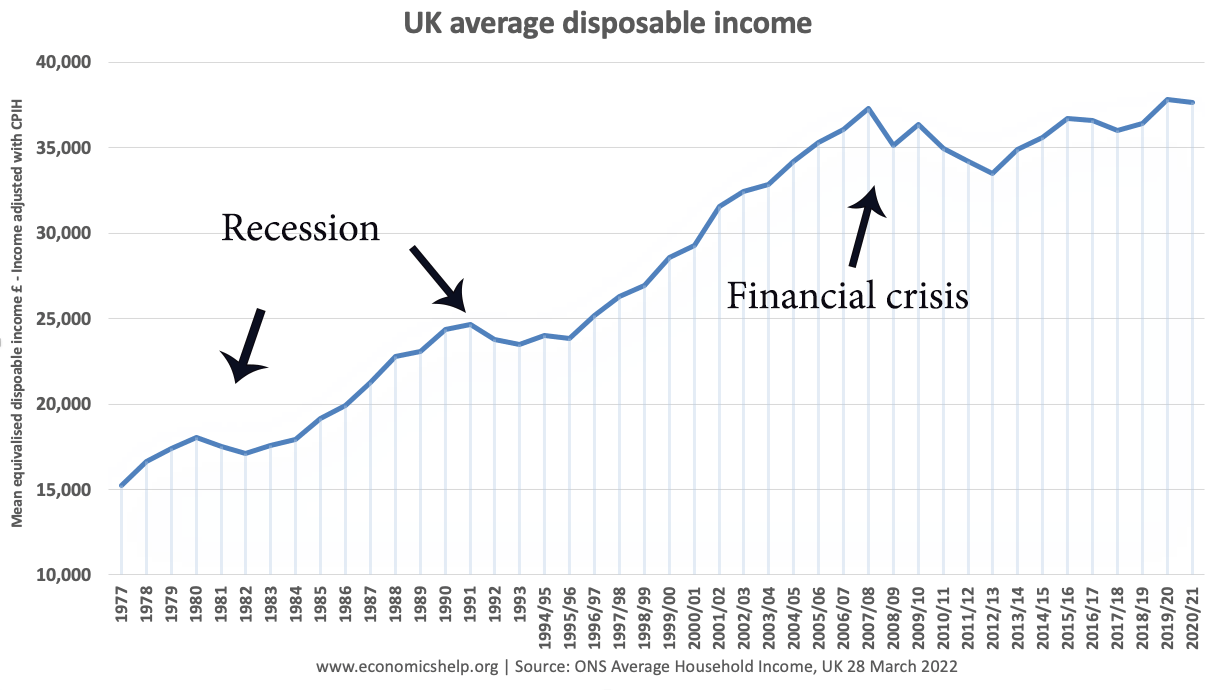

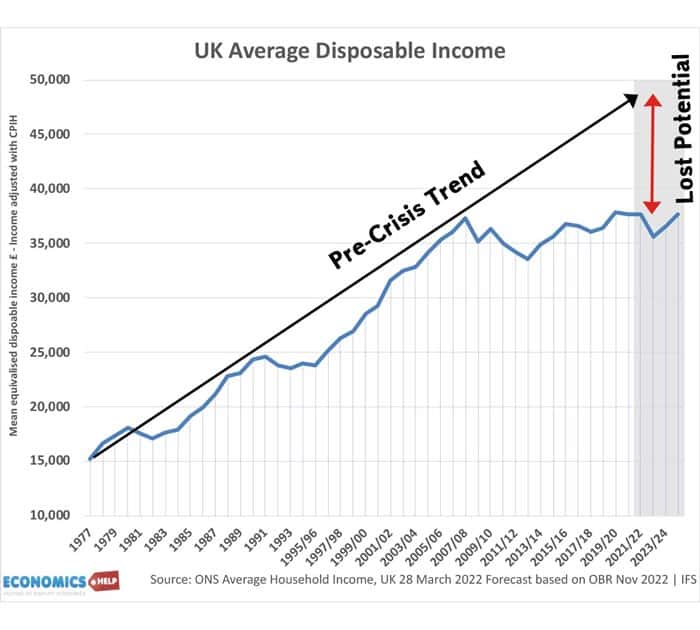

In the past 13 years, the UK has seen an unprecedented stagnation in real incomes. If Pre-crisis growth had been maintained, real incomes would be around £7,000 higher.

Whilst global events like Covid and Ukraine War are mitigating factors, the UK economy has still performed relatively worse, with one of the poorest performances in real wage growth.

Since 2016, business investment has been severely hit, which limits future growth. And recently, the IMF forecast the UK would have a lower growth rate than Russia. Given the record plunge in consumer confidence, it’s not surprising the Bank of England forecast a prolonged recession.

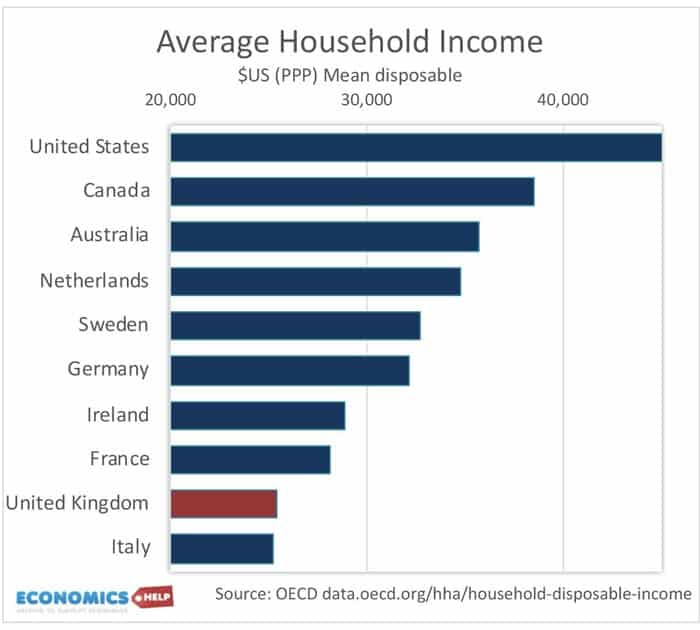

OECD stats highlight how average household incomes in the UK are around £9,000 lower than the average of five similar countries – Australia, Canada, Germany, France and the Netherlands.

The UK economy has been left behind and is starting to resemble Italy, which has experienced its own decades of economic weakness (and political volatility) The problem of low household income is also magnified by inequality. If you look at the earnings of the top 3%, the UK is among the top countries. But, as the FT reports the lowest-earning bracket of British households are 20% worse off than Slovenia. A big turnaround from the past 20 years.

So what went wrong?

There was no magic turning point. There have been complaints about UK economic underperformance since the Edwardian period saw the UK’s global pre-eminence being eclipsed by the US. In the post-war period, Britain steadily lost ground – with people pointing to poor labour relations, strikes, lack of investment, complacency and a governing class not enamoured with technological innovation. But, Britain’s decline wasn’t so visible given everyone benefited from rising incomes and prosperity. To put it into context, this is UK GDP since the 1800s.

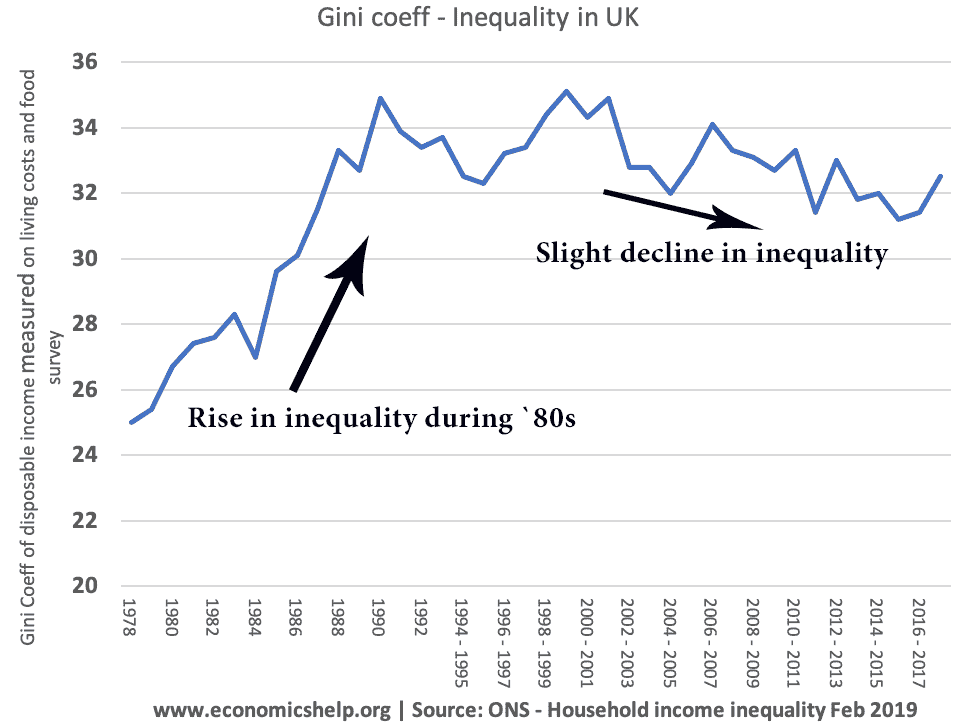

In the 1980s, inequality soared but because of strong economic growth, a majority saw rising real wages and rising wealth. However, the lack of any real wage growth has magnified many problems laying under the surface. The Resolution Foundation report there is no end in sight to the cost of living crisis. Despite benefits rising 10% in April, real incomes are expected to fall for the next two years – as low income families are particularly affected by inflation and rising food prices.

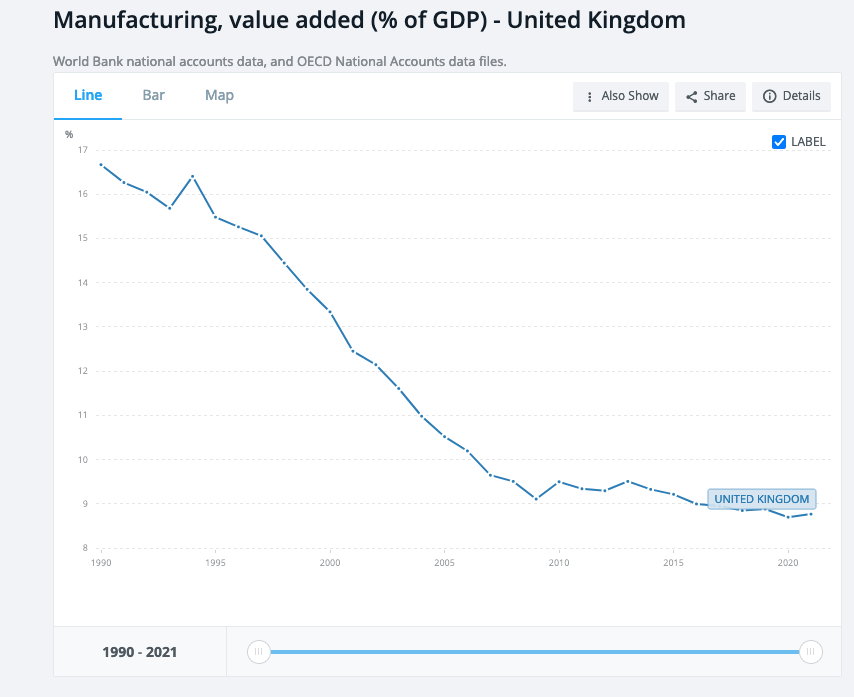

Another feature of the 1980s was deregulation and deindustrialisation. This meant by the 2000s the UK’s competitive advantage lay in services and financial services – which often includes servicing Russian and middle eastern oligarchs. This led to a major concentration of wealth in Greater London. In fact, it is worth pointing out, the UK has become much better at growing wealth than income in the post-war period. But the credit crunch hit financial services and therefore, the UK economy.

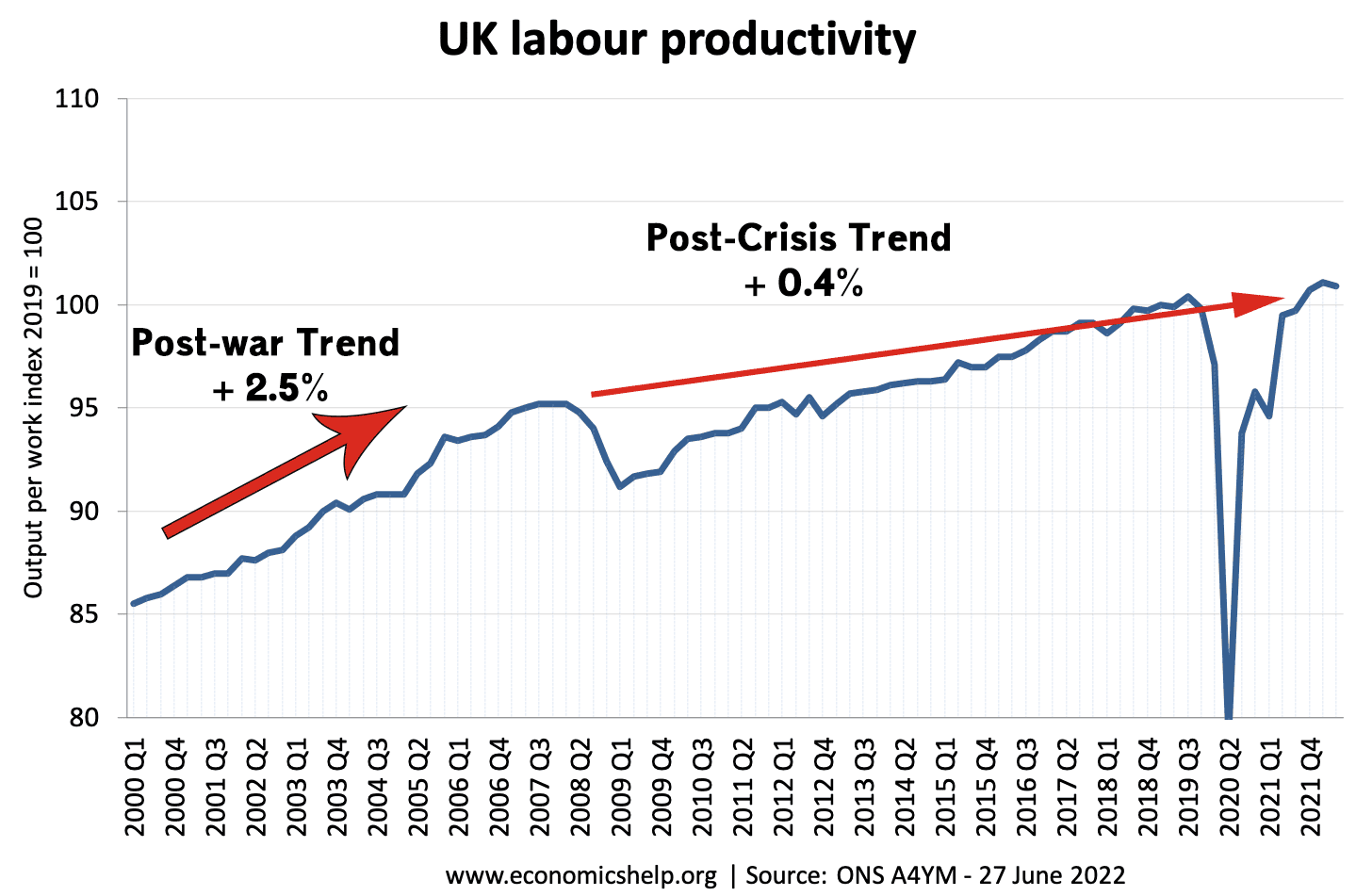

Since 2007, the UK’s productivity growth has slowed dramatically. Productivity is a key determinant of real wages. If firms can increase productivity, then they can pay higher wages. But, the weakness of business investment means the UK’s take-up of new technology is poor. Whilst we worry about AI taking jobs, the UK’s problem is that we have very low investment. Just 100 robots per 10,000 manufacturing workers – lower than Slovenia or Slovakia. To use a more mundane example, between 2003 and 2018, automated car washes declined 50% and hand car washes rose by the same amount It caused the economist Duncan Weldon to quip “It’s more like the people are taking the robots’ jobs.”

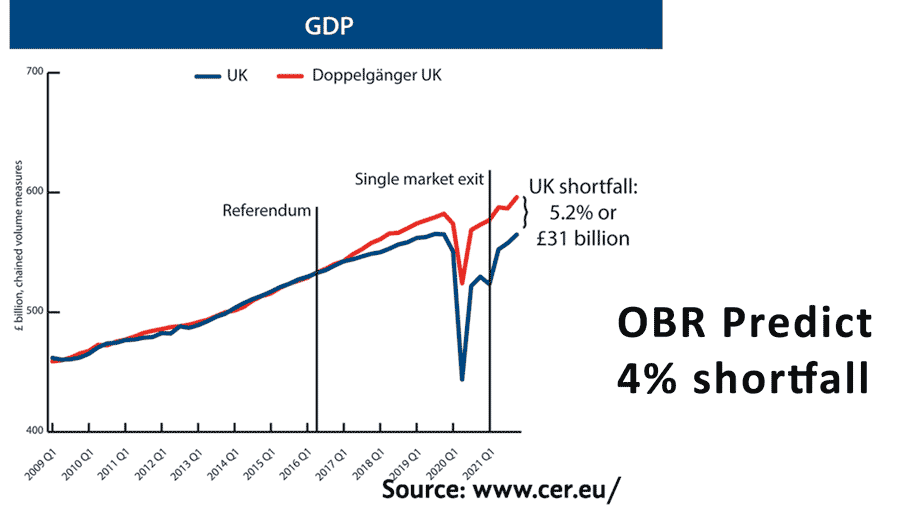

On top of this poor productivity and weak economic growth. The Brexit vote in 2016 led to more turmoil. A hope of Brexiteers was that ending free movement would be the decisive factor, which would end the UK’s reliance on cheap labour and lead to a surge in investment, productivity and real wages. Whilst it might be good in theory, real wages have not increased, and business investment has been curtailed by the uncertainty and costs of Brexit. Furthermore, the impact on trade and confidence led to a significant depreciation in the Pound, which has raised the cost of imports and reduced living standards. And the devaluation did little to improve the UK current account deficit indicating we import more than export.)

It is perhaps ironic that a key element of the UK’s early economic strength was free trade and openness. But, the hard Brexit deal has led to the creation of trade barriers and frictions with our biggest trade partner. The government point to Free trade deals e.g. with Australia but even best case scenario may lead to only 0.08% increase in GDP by 2030. The real Brexit impact is the loss of investment and output, which independent observers such as the OBR have cost the UK around 4-5% lost of GDP. The UK’s problems definitely predated Brexit, but so far Brexit has been another weight on the UK’s economic underperformance.

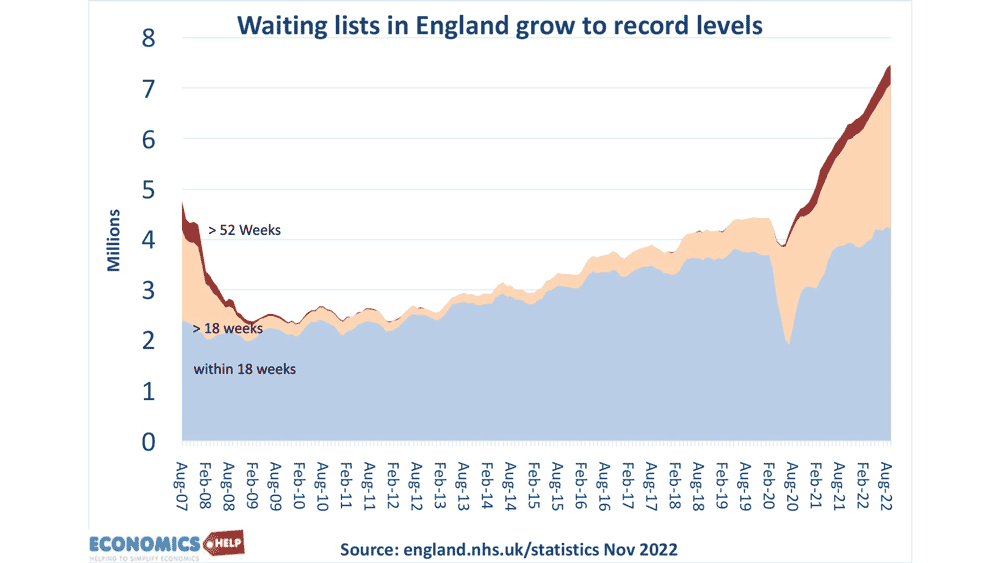

The low growth of the 2010s is at least partly attributable to fiscal austerity, which contributed to weak demand and investment. However, austerity caused more than weak demand, with pressures on public sector investment, and this is becoming visible with record waiting lists and falls in real public sector pay.

This is why despite stagnant incomes, there is a sense of being worse off. Many key public services are at stretching point, not being able to keep up with demand.

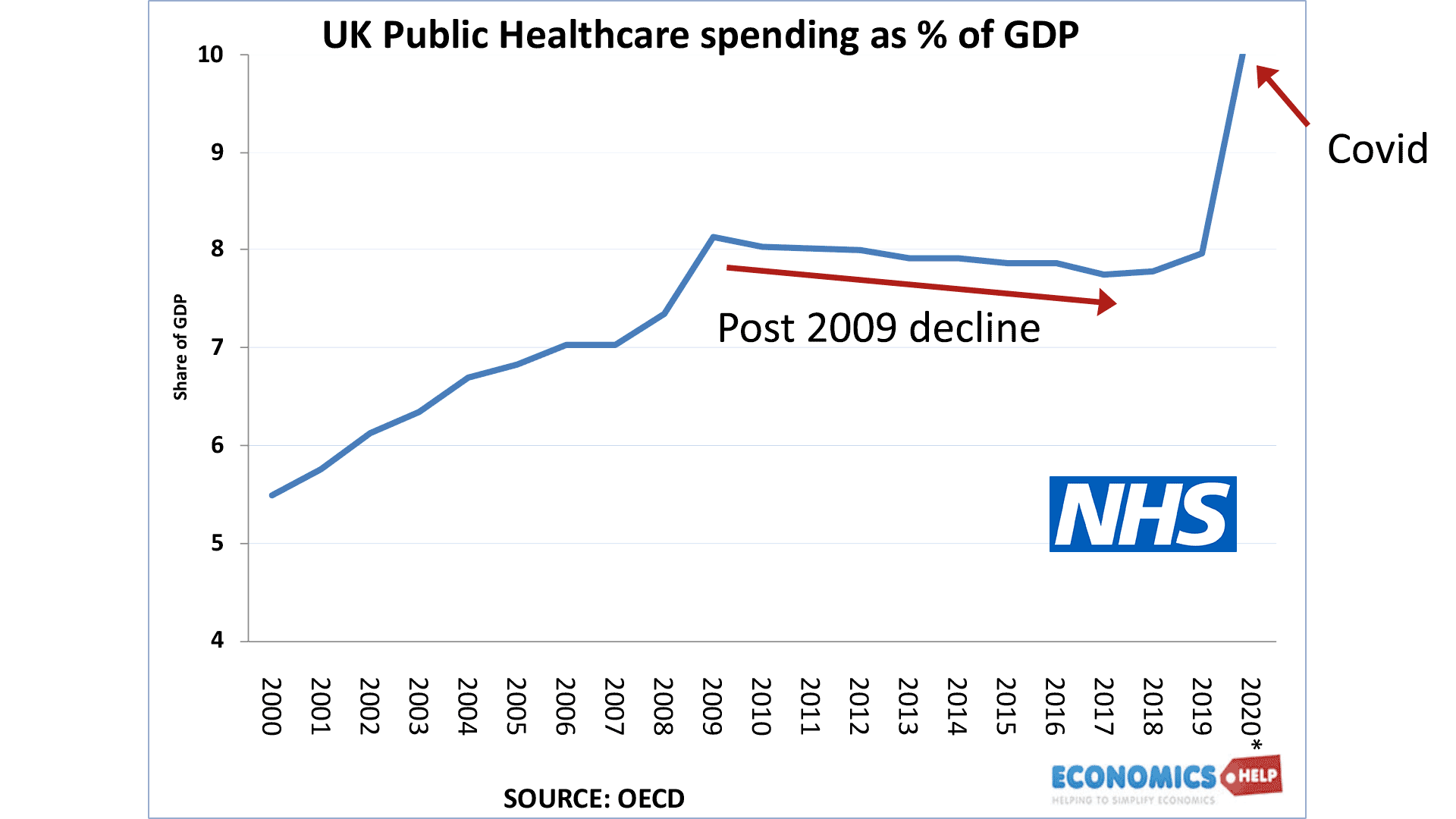

Despite rising demand, Health care spending as share of GDP fell during the 2010s. Combined with Covid, we have seen a rise in in long-term sickness and decline in labour market participation. This early retirement is not just due to ill health, but also some homeowners feeling confident to retire early. But, the consequence is a decline in labour participation and loss of skilled workers, which is a major factor contributing to low growth.

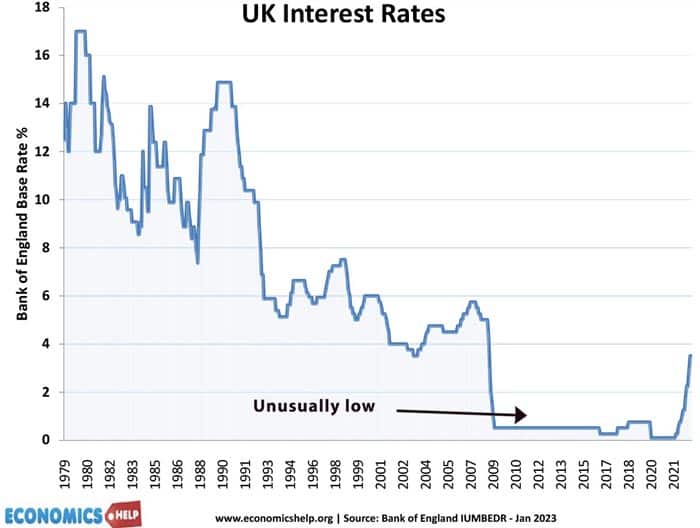

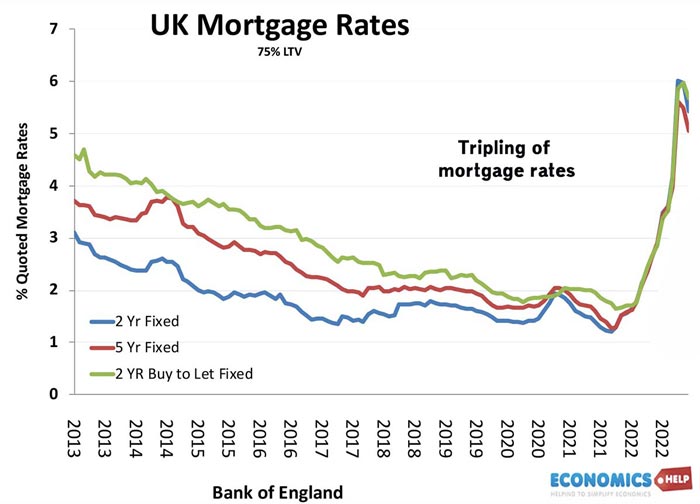

Another complication for the future of the UK economy is the end of the period of ultra low interest rates. In the 2010s wage growth was very low, but the pain was masked to some extent by very low interest rates. With interest rates of 0.5% it meant mortgage payments remained cheap – despite rapid growth in house prices. Zoopla report the typical monthly mortgage payment was actually lower in 2020 than in 2008. It’s not just cheap mortgages, cheap credit made it more attractive to borrow to buy a car. In the mid 2000s, 50% of car purchases were financed by credit.

In 2019, that rose to 90%. Rising interest rates have caused tracker mortgages to rise over £3,000 and those with fixed-rate mortgages will soon see rising costs. The rise in mortgage rates have pushed affordability back to levels seen in 1991 and 2007, which of course were points where house prices fell over 20%. A house price crash at this stage of the economic cycle, would further reduce confidence and wealth. And whilst we often focus on house prices, the rental market has arguably even more serious problems, with rapidly rising rents pushing many people into a situation of struggling to pay rent and bills. It’s another type of inequality in the UK economy.

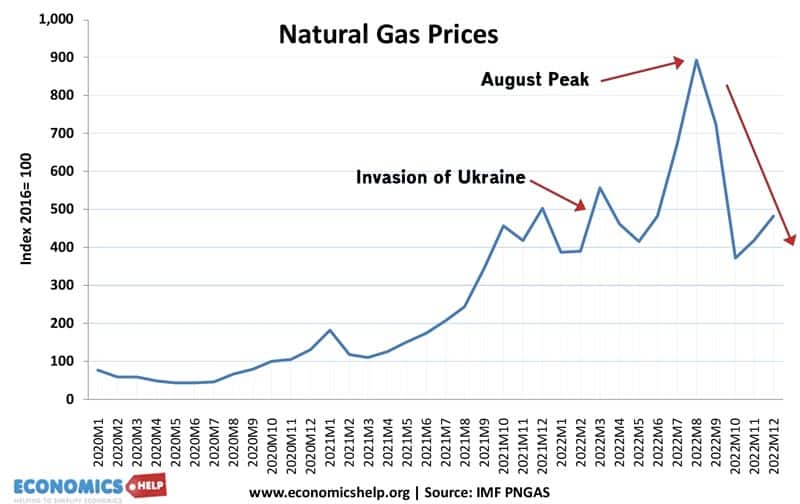

It’s always easy to paint a negative picture and get carried away with doom and gloom. There are some positive signs on the horizon Inflation is falling, and gas wholesale prices are falling and this should enable some increase in real wages by the end of the year. If inflation falls quicker than predicted the interest rate rises may peak soon. Energy prices will still be nearly double pre-2021 levels, but less than feared at the height of the Ukraine crisis.

Last month, government borrowing was less than expected and the deep recession forecast by Bank of England last year, may be slightly shallower than feared. Another factor is that if a country has years of below-trend growth, then in theory, there should be the possibility of catching up with lost growth, catching up with those neighbouring countries.

But, this improvement in short-term factors, doesn’t start to address the long-term issues which go back several decades.

Further reading