It’s not a good time to be a member of the Monetary Policy Committee. Inflation far exceeding forecasts and the Bank was forced into something of a u-turn belatedly increasing interest rates in a shock-and-awe tactic designed to regain credibility. Some critics argue the recent interest rate rises are like using a sledgehammer to crack a nut – engineering a recession and causing widespread economic pain a recession which will primarily fall on the most economically vulnerable. But, whilst it is always easy to criticise – is there any alternative, and what should the Bank of England be doing given the difficult choices facing them?

- Ultra loose monetary policy

The first failure of the Bank of England was to under-estimate the return of inflation. In 2021, the Bank continued with QE – even as global inflation started to rise. In 2020-21, the Bank of England implemented £400bn of QE, which combined with expansionary fiscal policy, was a large stimulus.

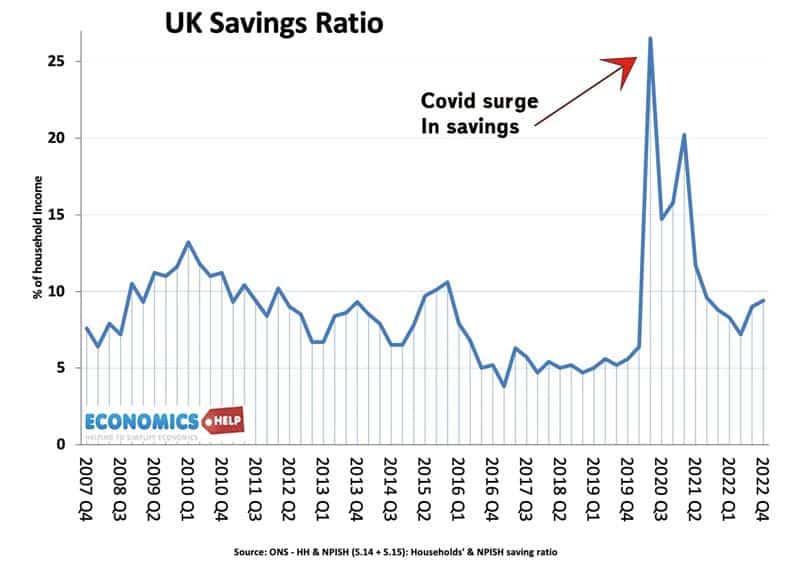

During covid, savings rates soared as many households saw a rise in disposable income. This contributed to a boom in house prices.

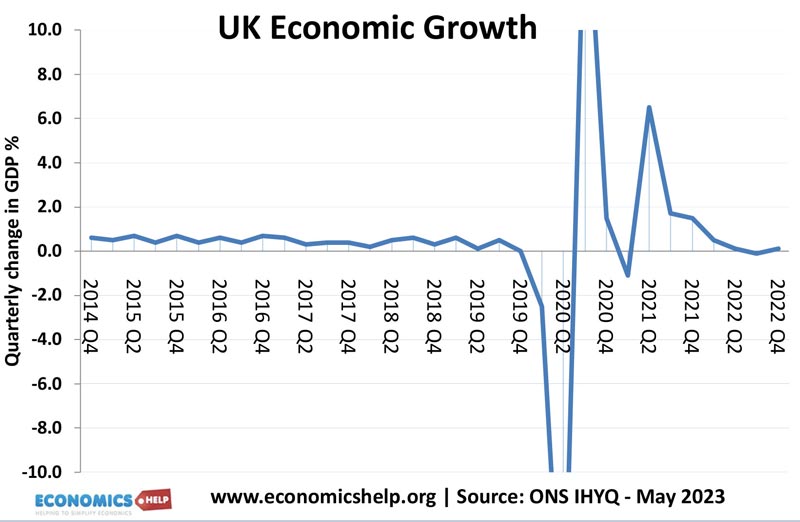

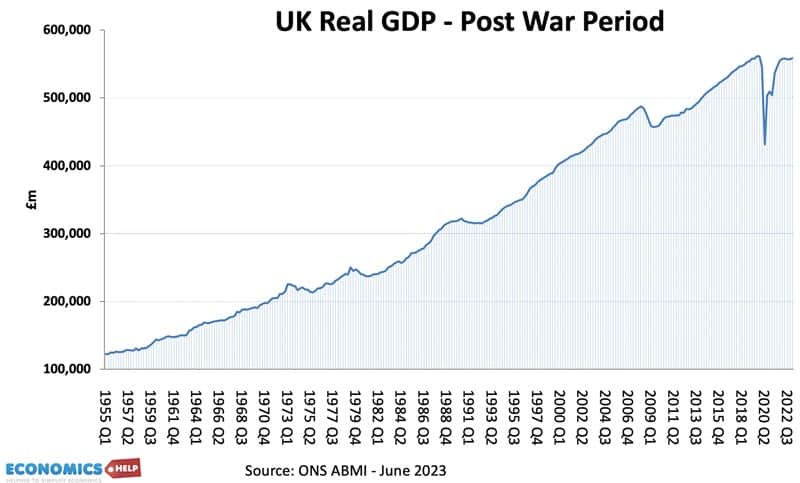

When the lockdown ended, GDP bounced back. The 2020 lockdown recession was kind of artificial. It was like turning off the tap, but when you opened the tap the pent-up water surged back. In 2021, Andy Haldane warned that due to higher savings, there was around £400bn (about 1/3 of UK GDP) of household and company savings which would be seeking a new home.

- Underestimating inflation

On its own, the stimulus might have caused only limited inflation – inflation that may have been controllable, but combined with all the Covid-supply shocks, followed by rising oil and gas prices, inflation crept up.

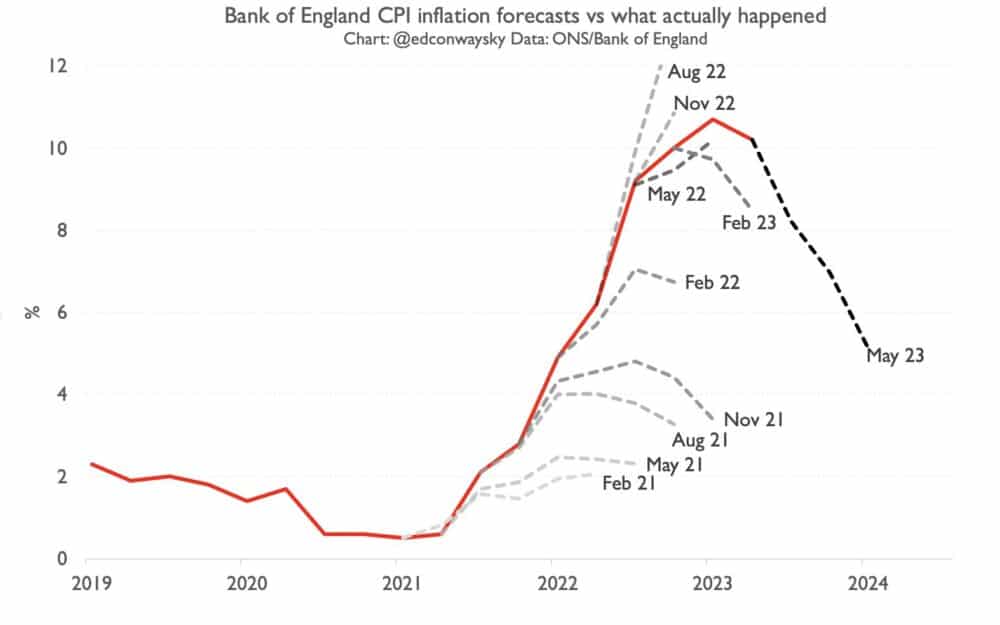

Unfortunately, there is no doubt that the Bank of England forecasts persistently underestimated the scale and duration of high inflation. Not only that, but UK inflation has been one of the highest in the developed world. This is not necessarily the Bank of England’s fault. Brexit supply shocks have contributed to food inflation. The UK was also particularly affected by rising gas prices. But, by getting behind the curve, inflation has become more embedded, leading to a rise in core inflation. Even at the start of the year, the forecast was for inflation to fall back to target by 2024, but unfortunately, this has been missed.

Wrong model

There is a saying economists often end up using past models for today’s problems. After the 2009 financial crisis, QE and ultra-low interest rates probably helped stave off a deeper recession. You can criticise QE for its side effects on asset prices, but, without QE, unemployment could have been higher. When we got some cost-push inflation in 2012, the Bank correctly predicted it would be temporary and soon fall which it did. But, the 2020 Covid recession was not a structural financial collapse like 2009, the scale of QE in hindsight was over-generous. When inflation rose in 2021, there was a hope it would be like 2012, temporary and short-lived. But, this was not to be the case

Difficulty forecasting

Economic forecasting is a tricky business, especially in a period of global volatility, getting forecasts wrong is part of the trade. The real question is what do we do now that inflation is stuck at 8.7% significantly above target. The Bank has decided they will go for a shock and awe approach, raising interest rates more than expected and hinting they could rise to 6%. The logic is that this will reduce inflationary expectations and make it easier to bring inflation down. The Bank argue that if they don’t act, nominal wage growth will continue to rise, causing even more inflation and more pain in the future, and maybe even higher rates will be needed.

Concerns of Bank of England Approach

However, there are a number of concerns with this approach. Firstly, in 2022, the Bank of England’s own stress tests suggested that interest rates of 6% would cause an economic crisis on par with the financial crisis of 2009 and house prices could fall 30%. Now this stress test now looks outdated given the Bank’s underestimation of inflation. But, it is worrying that interest rates could rise to a level the Bank used to think would cause an economic crisis.

Time lag

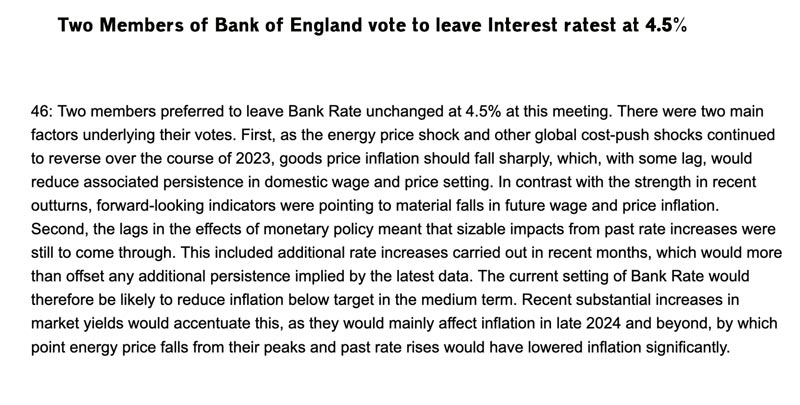

Secondly, interest rates have a time lag of up to 18 months. This means the past 12 interest rates will not have their full effect on reducing inflation until 2024. This week, two members of the Bank of England voted to keep rates at 4.5% their logic was that.

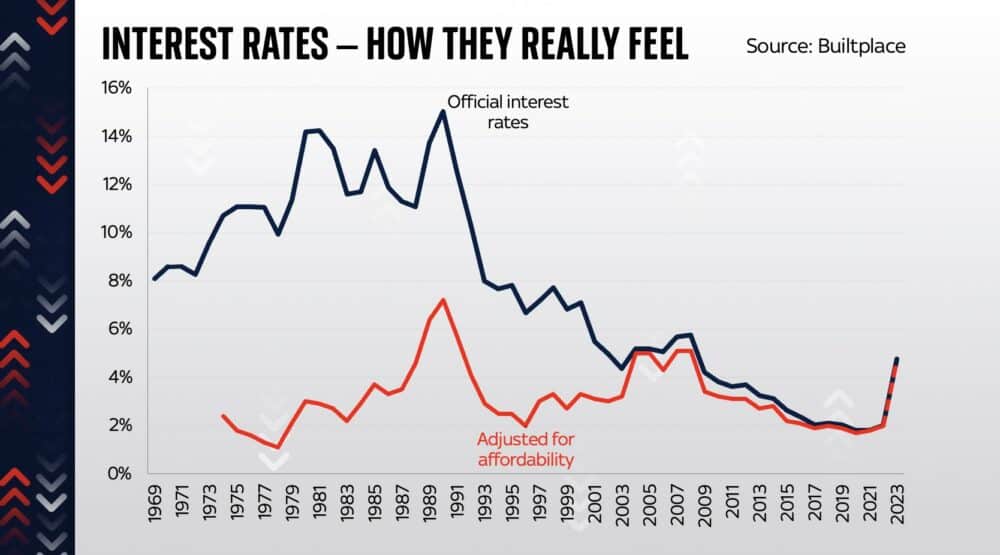

Firstly, energy price shocks continue to go into reverse. Next month gas and electric prices will fall – This isn’t just a fall in energy inflation but a negative inflation rate. This will reduce goods price inflation, and with some lag start to reduce wage growth. Secondly, they point to the time lags of past interest rates that are still to be felt. At this point, further rises in interest rates risk an unnecessary recession and inflation falling below target in the medium term. Also, due to very high house prices, interest rates have a much bigger impact on mortgage payments than in the past. An interest rate of 6% is equivalent to 13% in the past.

Economist Richard Murphy argues that rapid increases in interest rates can also have their own inflationary effects. Firstly, it causes an increase in mortgage costs rise which is measured by CPIH. We can see the rate of Owners’ Occupier costs has increased sharply since rates started to rise. Though CPI inflation excludes these housing costs.

Secondly, higher interest rates will increase the cost of borrowing, which firms may pass on to consumers. This may be important in areas like car leasing which is related to interest costs. Thirdly, higher interest rates could feed through into higher rents as landlords try to pass interest rate costs onto tenants.

It is an interesting point that higher interest rates can cause their own short-term inflationary pressures, but it shouldn’t be overstated. It is only one business cost out of many. If we take say food inflation running at 18%, indirect interest rate costs are only a very small factor. Also, higher interest rates tend to cause an appreciation in the Pound and reduce import prices.

Problem of increasing interest rates in times of Stagflation

The real problem with increasing interest rates at the moment is that the UK has a kind of stagflation – high inflation and low growth. The UK is barely avoiding recession – only growing 0.1% last quarter. In this climate to reduce inflation by slowing down spending and growth is like squeezing a dry sponge, you only get a few drops of water for the amount of pressure you apply. To reduce inflation by higher interest rates requires a lot of pain and a pain that is focused on a relatively small share of the population. E.g. people who took out large mortgages recently. This also raises the problem that interest rate affect a smaller share of the population than in the past because more young people haven’t been able to buy and the broad effects of higher interest rates aren’t the same as in the past.

Monetary policy works best when it is in response to strong growth. For example, in 1998, the Bank of England increased interest rates to 8% in response to strong growth. This rise in rates kept inflation close to target but didn’t cause a recession or unemployment. Growth continued to be close to the long-run trend rate of 2.5%. You could say this was the ‘golden period’ of Central Banks the goldilocks economy – low inflation, strong growth and falling unemployment. It shows that higher interest rates don’t have to cause economic misery, but can finely tune the economy. But the 2020s are a very different economic climate to the 1990s. In present circumstances interest rates become a blunter tool, the ability to fine-tune the economy is lost.

What is the alternative?

If I was on the MPC I would have voted with the two members who voted to keep interest rates at 4.5% . And that is not because I have a tracker mortgage! With falling energy and food prices. Inflation will come down. Core inflation has risen to concerning levels, but I’m not so worried about a wage-price spiral because workers have weak bargaining power in the UK. Despite labour shortages and record vacancies, wages have fallen behind inflation. Their weak bargaining power is highlighted by the fact that real wages have consistently fallen. An alternative to controlling inflation is to use fiscal policy. If there is a need to reduce demand, a higher income tax is a broader-based and more effective method to reduce spending. Also, the government could reduce VAT to reduce the price of goods directly. This would give a temporary fall in inflation, which in the current climate it would help change expectations and give the fall in inflation a real boost.