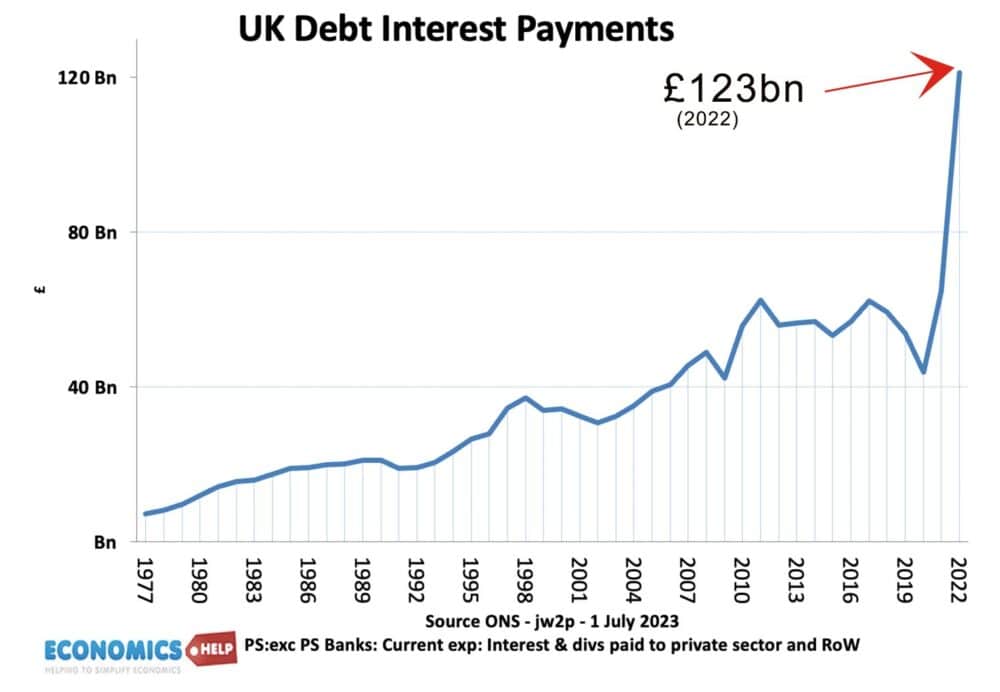

The economist recently warned that governments are living in a fiscal fantasyland, failing to confront dire and growing levels of debt. High inflation and rising interest rates have caused a surge in debt interest payments.

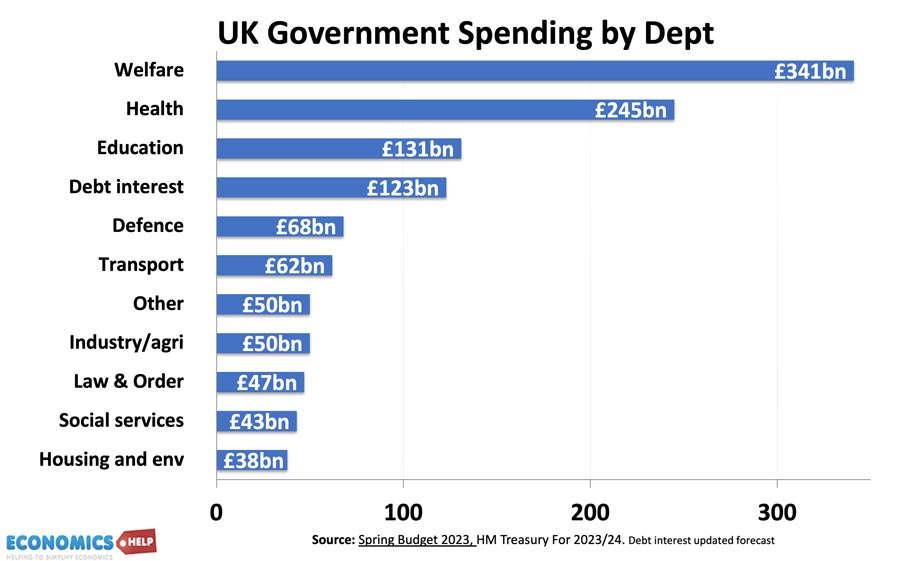

By next year, the UK’s debt service payments will be similar to the entire education budget.

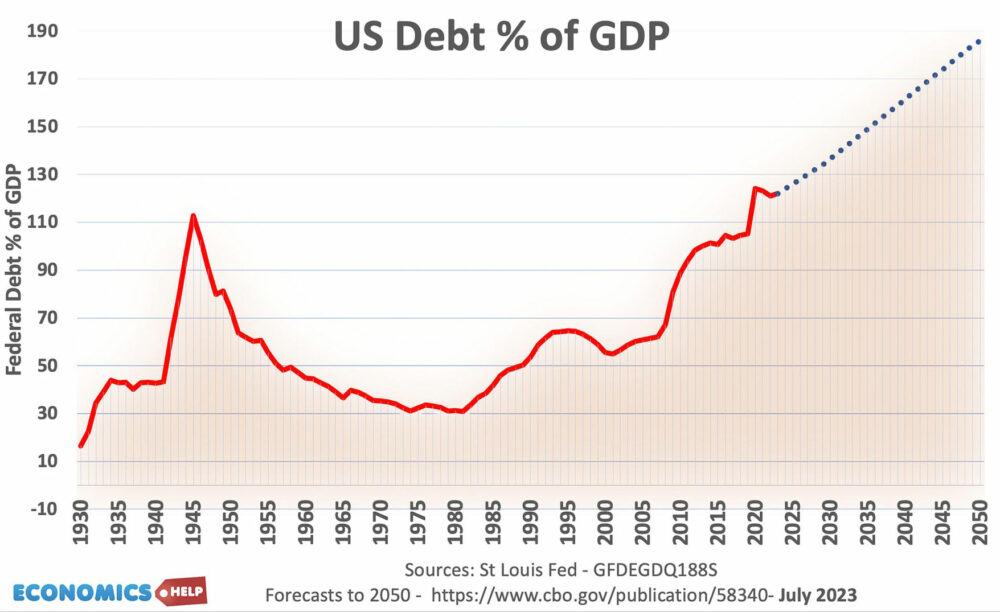

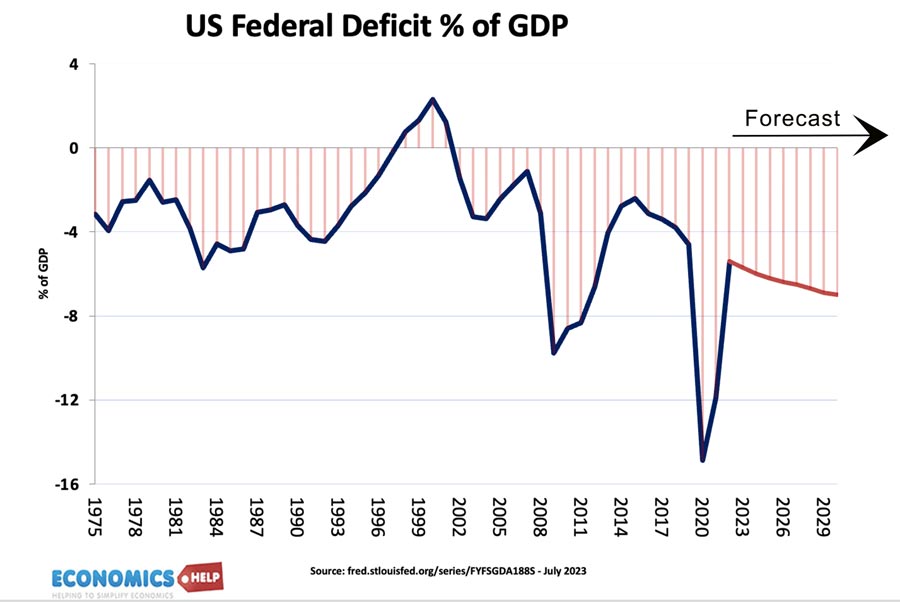

It is a similar story in the US where the deficit is expected to soar in the next 10 years, with a corresponding rise in federal debt.

This debt crunch comes at a time when Western economies face slowing economic growth and an ageing population. All of which places increased pressure on government spending. But how much should we really worry about debt? and does it mean we can no longer afford investment in housing and a green economy?

The Last Debt Crunch

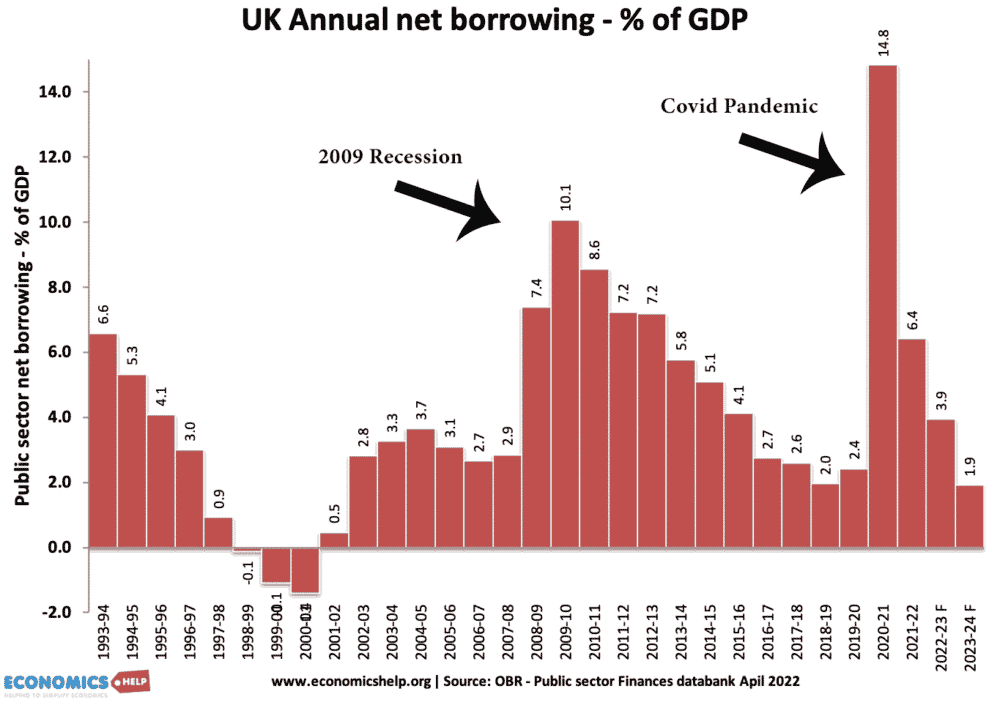

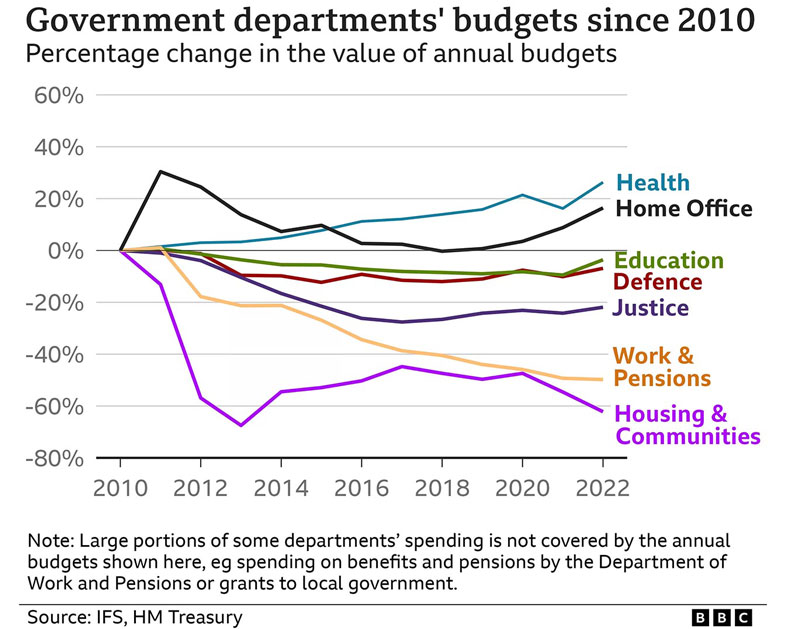

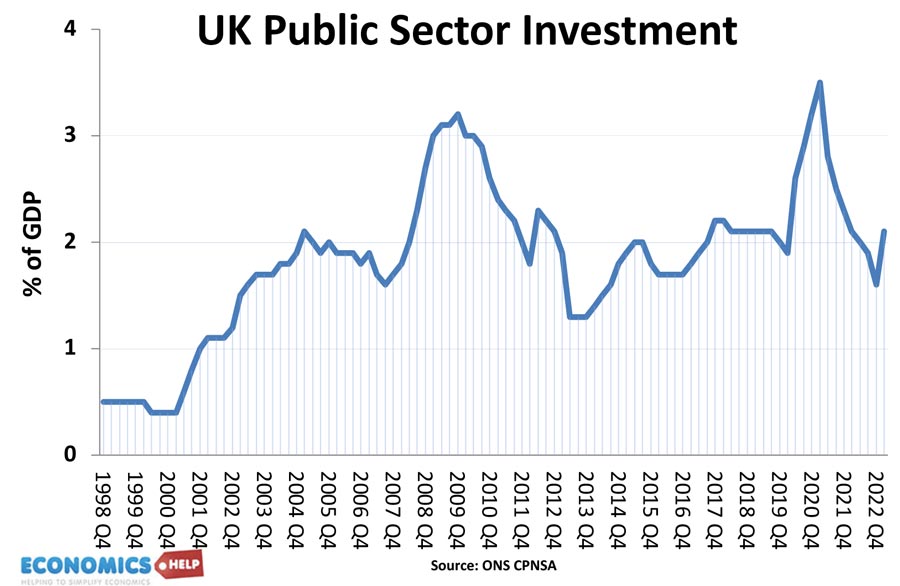

Back in 2009, the UK budget deficit soared in response to the financial crisis. Fears over debt dominated the 2010 election and were a factor in the Conservative’s winning. There followed years of austerity, with spending cut in many departments, such as public investment.

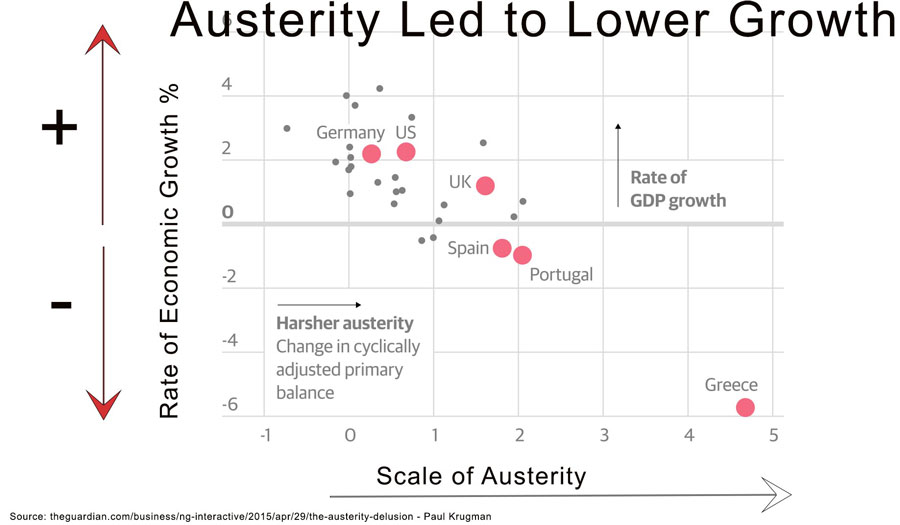

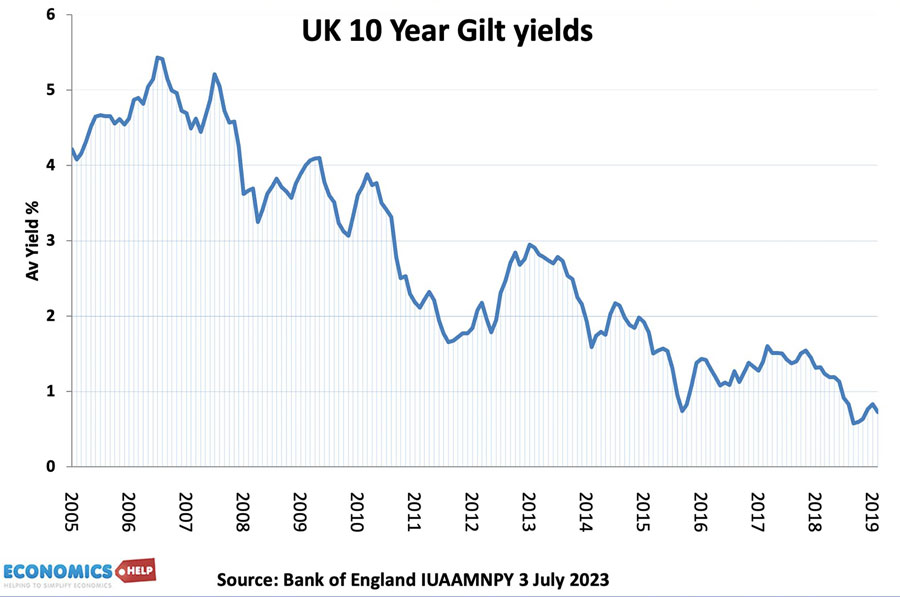

However, fears over debt seemed misplaced as interest rates fell to record low levels. Helped by quantitative easing, which involved the creation of money to buy government bonds. The cost of debt interest payments fell and there was strong demand for buying government bonds from the private sector. Not only that but there was a fairly strong link between austerity and lower economic growth, which ironically harms public finances by reducing tax revenues.

The costs of austerity were most strongly felt in southern Europe, where efforts to improve public finances led to sharp economic downturns. By 2020, after 13 years of low interest rates, governments were more relaxed about higher borrowing and Covid lockdowns led to generous fiscal support accompanied with more QE

From 2008 to 2021, there was very little cost to adding to public sector debt, and given all the political pressures to cut tax and spend more, it is unsurprising debt as a share of GDP rose across the developed world.

Inflation and Interest Rates

However, this debt dynamic has changed quite dramatically since 2021 due to the re-emergence of inflation and higher interest rates.

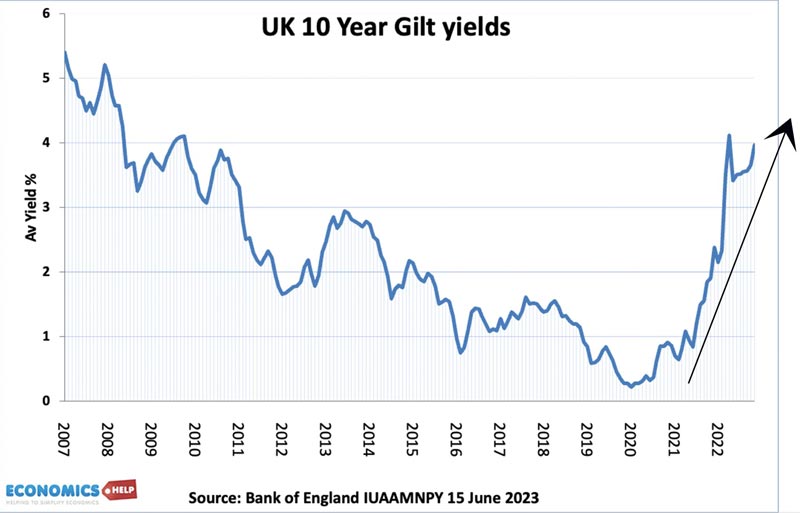

In 2020, UK bond yields reached 0.2%. The government could borrow almost without cost. But, since rising to 4.3%, the cost of debt interest payments has soared.

Also, the UK sell many index linked bonds. This means the debt interest payments depend on inflation. The unexpected high inflation was part of the reason for the surge in debt interest payments.

In September 2021, the UK government under Liz Truss announced a substantial package of tax cuts in a bid to boost economic growth. However, markets reacted badly for many reasons. Firstly, the UK had already had inflation of 9%, and large tax cuts created more inflationary pressures. Therefore, markets demand higher bond yields to compensate for the expected rise in inflation. Interest rates soared and this led to something of a market panic. By increasing the budget deficit from £90 to an estimated £190bn, it also put rising government debt back in focus.

The interesting thing is that if Liz Truss had implemented that budget any time between 2010 and 2020, there wouldn’t have been the same (if any) surge in interest rates. In the 2010s, we were in a liquidity trap – low inflation and low interest rates. The markets would have absorbed the extra debt. But, when inflation is significantly above target, when interest rates are rising, it is much harder to dramatically increase government borrowing. It was a shock because for 13 years bond markets had been very predictable. But like a sleeping tiger it suddenly woke up.

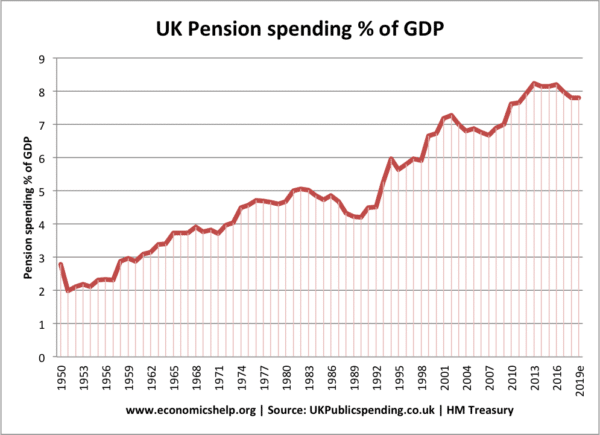

Demographics and slow economic growth

There is another reason to be concerned about levels of government debt and that is demographics. We have an ageing population and this basically means higher spending on pensions and health care. Even if budgets remain neutral, demands on government spending is likely to grow faster than tax revenues. When we talk about austerity in the 2010s, it is important to bear in mind that spending on health care grew in real terms quite substantially. Yet, despite higher spending, it wasn’t enough to prevent a growth in waiting lists and decline in standards. Healthcare spending has grown not just in real terms, but as a share of GDP. As people live longer and there are more medical treatments there is always more to spend on. This trend is only likely to continue. If anything there is a need to increase spending to deal with backlogs.

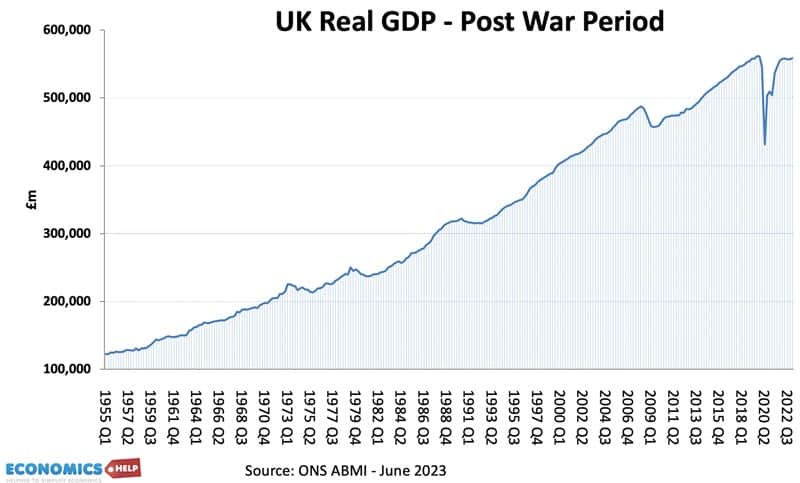

On its own demographics is not necessarily a problem. We have had an ageing population for the past few centuries. If the economy and productivity is growing, then we can afford to spend longer in retirement, we can afford to devote more resources to health care. The real problem comes when economic growth slows down to a trickle. The UK has been particularly affected by lower growth, GDP has fallen behind its post-war trend rate meaning there is just a smaller economic pie to be distributed. In the past governments could rely on growth to increase tax revenues. But, now something has to give – it’s either more debt, higher taxes or spending cuts.

Poor economic growth goes back to 2009 and is due to many factors from low productivity, low investment to Brexit. The big question is whether the past 12 years is an aberration or the new normal. But, recent years don’t look promising for the UK with very low growth and inflation creating very pessimistic forecasts.

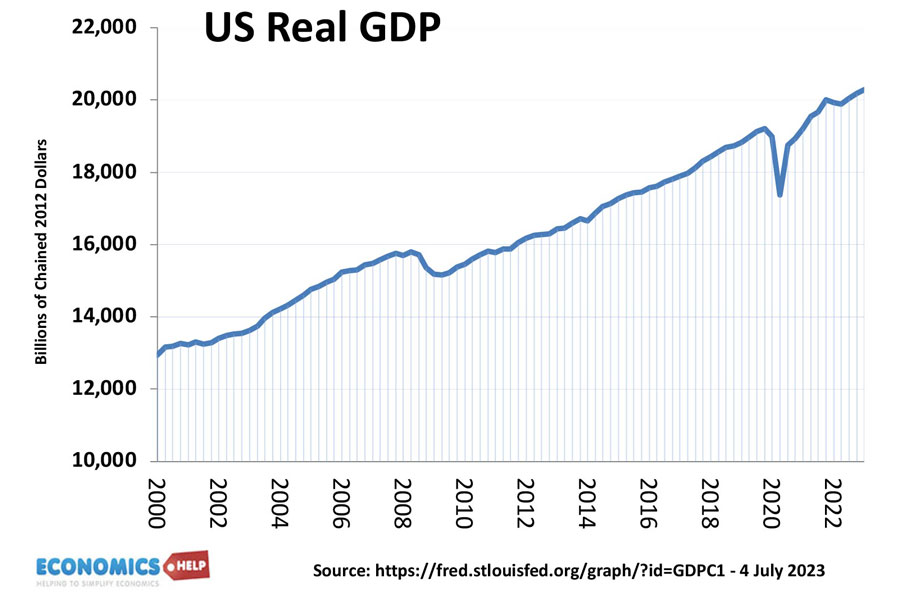

On a brighter note, the US economy has actually performed quite strongly, suggesting low growth is not an inevitability for modern Western economies.

But, even with relatively good US economic growth, they are seeing the forecast budget deficit rise to 7, 10% which is unprecedented given the state of the economic cycle. A lot of this increase is due to rising interest payments. The gravy train of cheap government borrowing appears to be over for the moment.

Should we fear Debt?

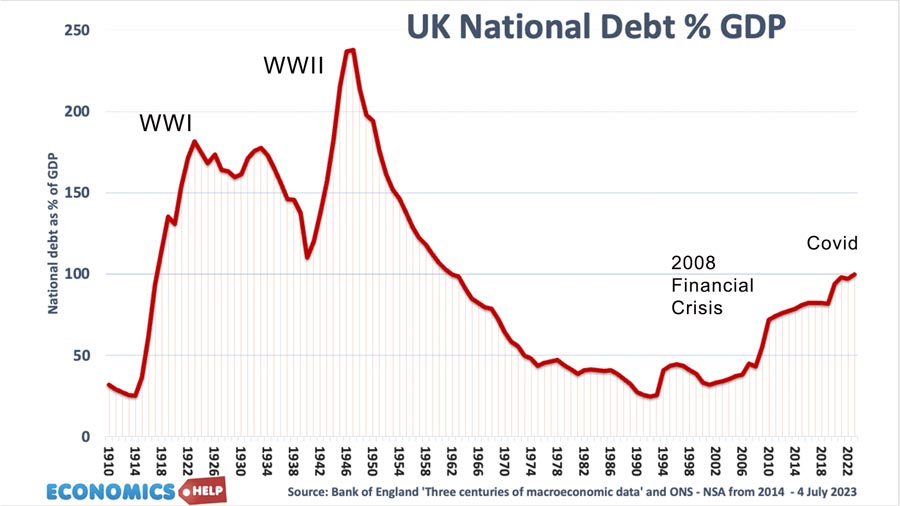

Are debt fears overplayed? In the 2010s, when I started writing about economics, I felt the push for austerity and fears over debt were misplaced. For a start, the UK economy has had much higher debt in the past.

In the post-war period, Britain was nearly broke with debt at 180% of GDP. But, despite this debt mountain, the UK invested in housing and set up a welfare state. In the 1950s, public debt rose to a mouth-watering 240% of GDP . But, did these debt levels destroy the economy? Actually the reverse, it paved the way for a long-post war economic boom and for the next four decades debt as a share of GDP steadily fell. So when people warn about debt levels, bear in mind, there’s no hard and fast rule what is unsustainable. But, before, we open the government chequebook and splurge on debt, there are some reasons to be cautious. The UK survived with a big loan from the US. In the post-war period, inflation was generally low and economic growth was very strong and we had the baby-boomer generation plus migration helping to increase the population. The outlook in 2023 is different, it’s hard to see the same decades-long economic boom, at least in the medium term.

Does it mean we can’t afford to invest?

It is important to make a distinction between borrowing to fund pension spending and borrowing to fund public investment, such as improved energy production. If we invest in green technologies, there will be a future economic benefit of cheaper domestically produced green energy. This will be very useful both for the environment and the economy. For example, the surge in oil and gas prices in 2021 caused huge economic costs to the UK because we are dependent on importing gas. Even Ken Rogoff a leading proponent of austerity in the 2010s, said public investment should be excluded from austerity as it is important to increase economic growth. In many ways, the 2010s were a missed opportunity to invest in housing and renewable energy. If the UK was more energy reliant, it could have avoided some of the inflationary shocks.

Liquidity

Another point about debt is that if you have your own currency, then if there is a liquidity shortage the Central Bank can always print money and buy government bonds. This is why the UK avoided the Euro debt crisis of 2012, but those in the Euro got stuck. A central bank who can print money gives considerably flexibility, but it is not a blank cheque. In a period of inflation, the ability for a central bank to create money to buy bonds is constrained by the inflationary impact. Even the most ardent modern monetary theorists argue that the ability to borrow is constrained by inflation. This is the difference between 2023 and 2013. As mentioned before, high inflation is also increasing the cost of debt interest payments because of index linked bonds and the need for higher rates.

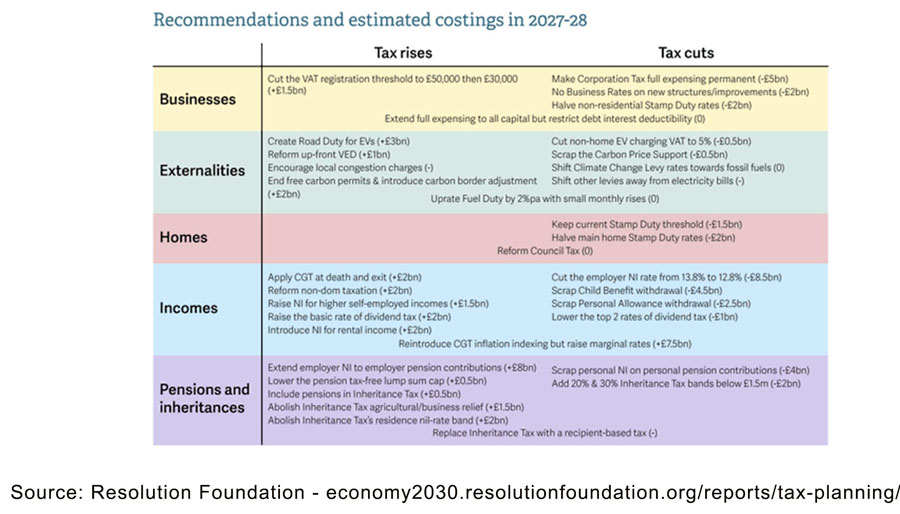

The UK should not use debt as an excuse to stop public investment, but there needs to be a more honest conversation about how to fund future spending. The Resolution Foundation give many good suggestions on raising money, such as road pricing on EV, tax on property, carbon taxes, and abolishing limits on NI. One of the easiest fixes to the problems of an ageing population is actually to encourage immigration, but it comes with pros and cons when there is a shortage of supply of housing.

Future forecasts over debt are always uncertain. We have had two big shocks in the past three years – Covid and energy prices, which caused an unexpected surge in debt. How many more shocks will there be in the next 10 years?

A lot depends on economic growth and inflation. If we were to return to 2% economic growth and inflation fell, a lot of concerns would soon ease. But, if a kind of stagflation is the new normal, there will be very uncomfortable choices for governments as painful choices need to be made.

Further reading