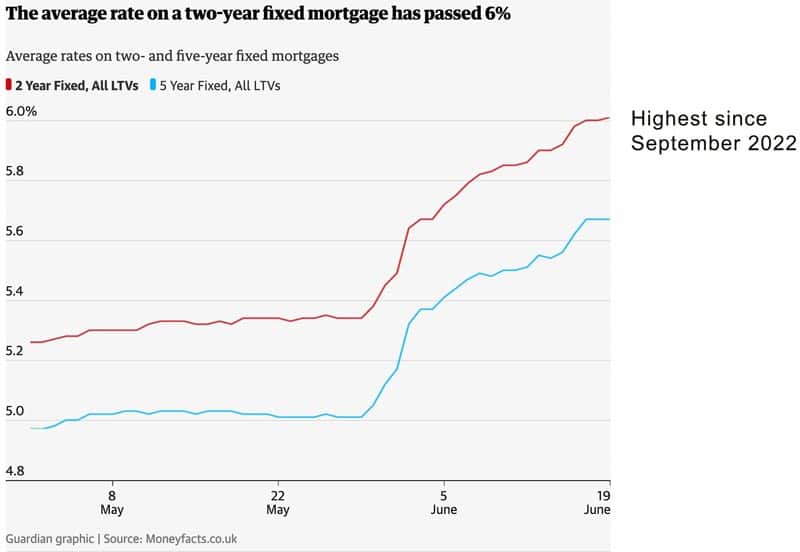

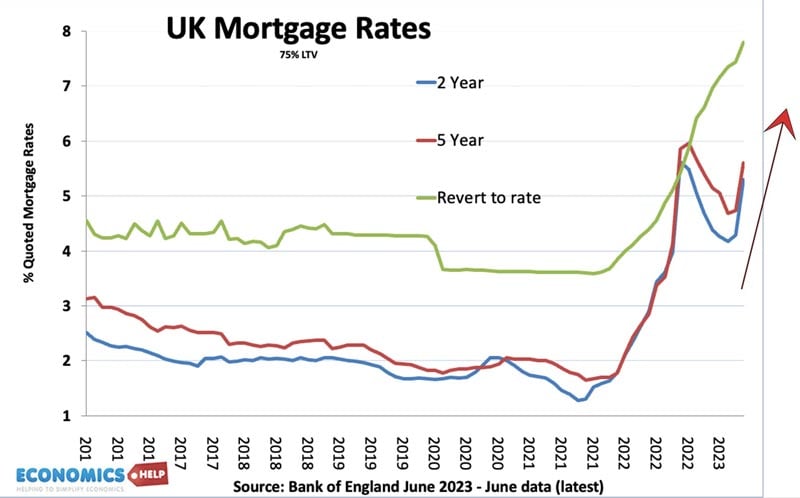

This week 2 year fixed mortgage rates rose above 6% – the highest level since Liz Truss’s mini budget of September.

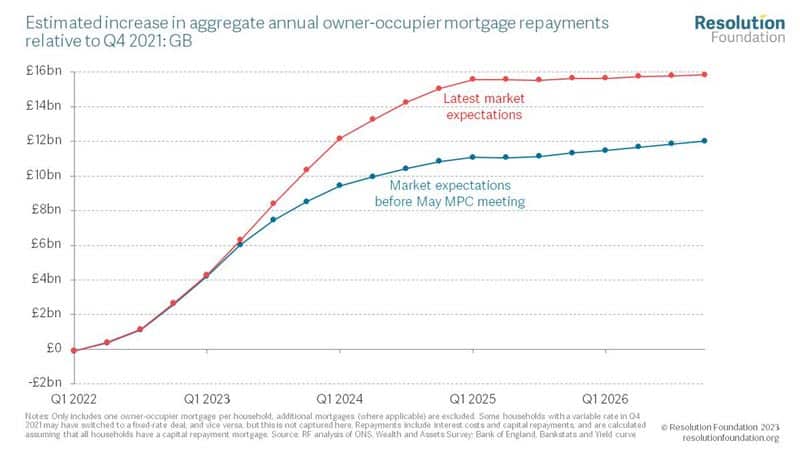

It threatens to add an extra £2,500 a year to the average mortgage. By next year, total mortgage payments could be an extra £14bn compared to 2021.

Whilst the September surge in rates was closely linked to an extravagant budget of tax cuts, the current rise in mortgage rates is looking more difficult to reverse, with profound impacts on house prices and the economy. How did we go from 12 years of ultra-low interest rates to the biggest mortgage crunch since the early 1990s?

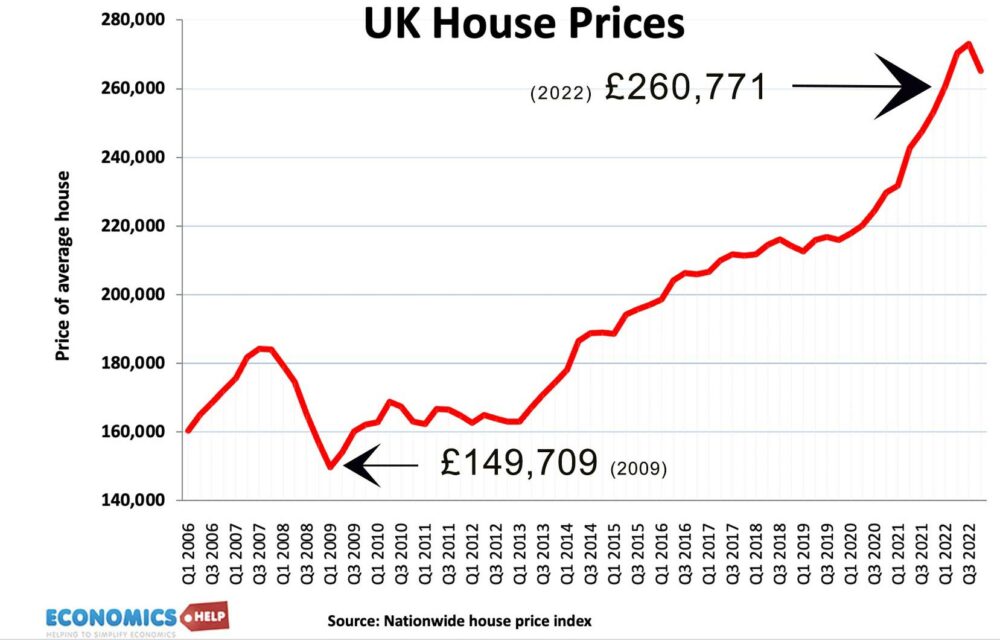

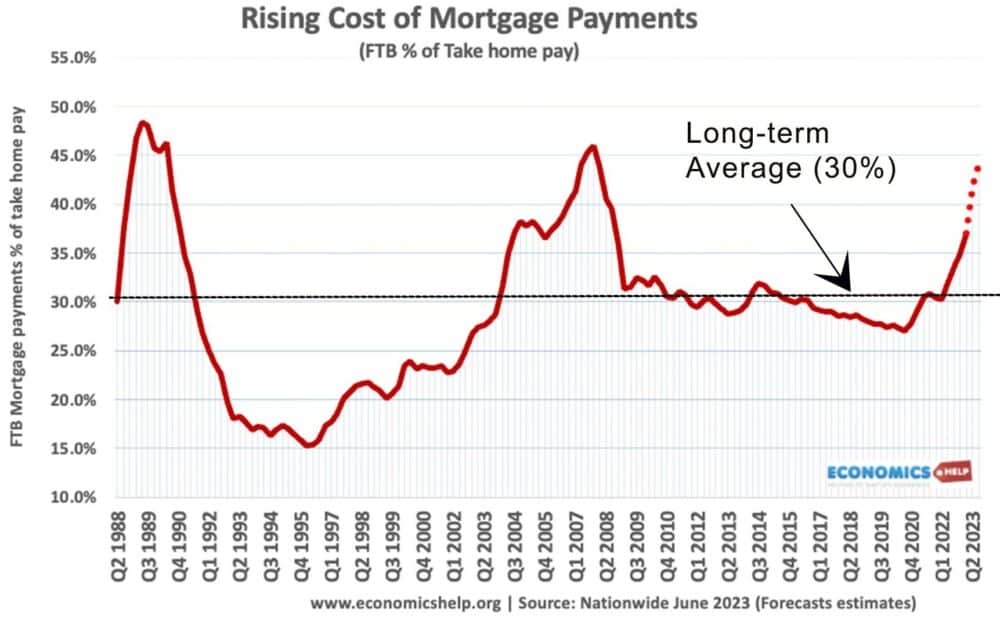

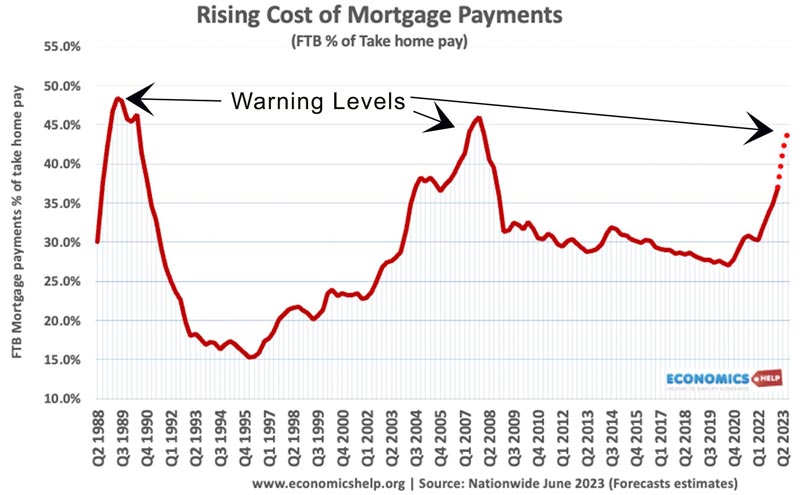

In 2009, average house prices were £149,709 and first time buyers were paying 32% of their income on a mortgage. 12 years later house price had increased 75%, and yet first time buyers were only paying 30% of their income on mortgages.

Until 2022, despite rising house prices, mortgage payments as a share of income remained constant around 30% of income. However, the rise in interest rates risks causing mortgage payments to soar to levels not seen since 2008 and 1991.

Homeowners were rational in taking out ever bigger mortgages, despite very high house prices, because the cost of borrowing was so cheap. Why pay £1,500 monthly rent “dead money”, when you can take out a mortgage at 2%? Not only that, but the UK’s obsession with the housing market meant the government were helping people get bigger mortgages with help to buy.

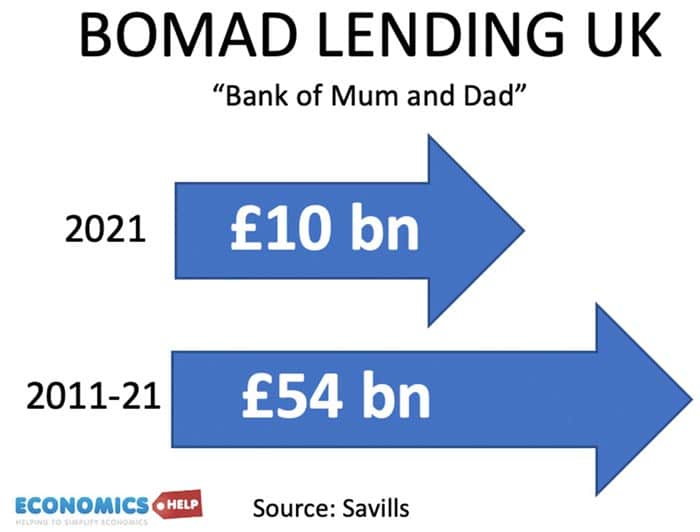

Also, very important parents who had seen big wealth increases themselves, helped their children with deposits to buy. The result is a surge in average deposits. An estimated £54bn parental wealth entered the housing market between 2011 and 2021, all helping to push up the long-term house price to earnings ratio.

And on top of that the Bank of England’s £700bn of QE has helped to further inflate asset prices.

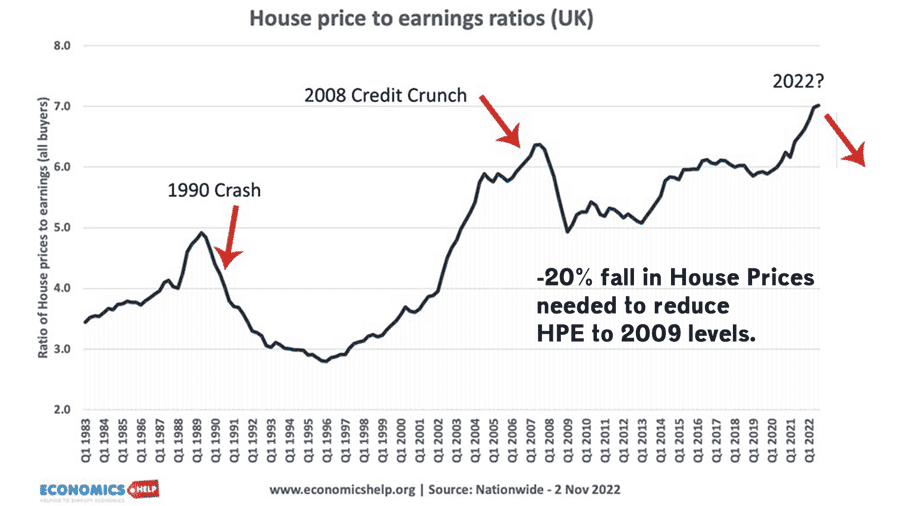

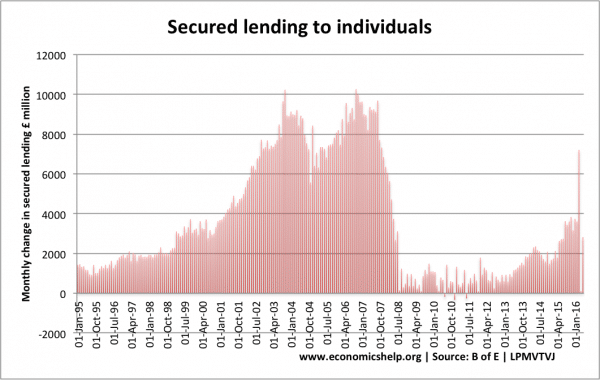

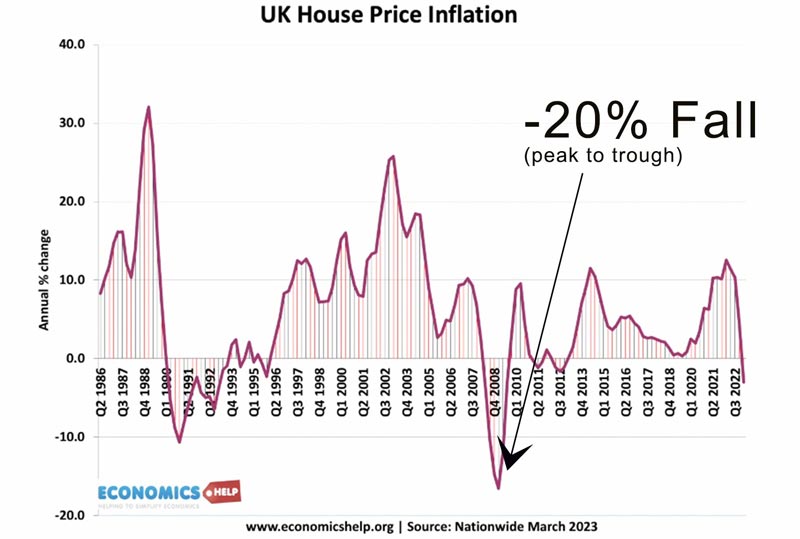

Back in 2009, the global credit crunch hit the banking sector with great force. The government was forced to bailout banks like Northern Rock and Lloyds. The credit crunch led to a dramatic drop in bank lending, a deep recession and a 20% drop in house prices.

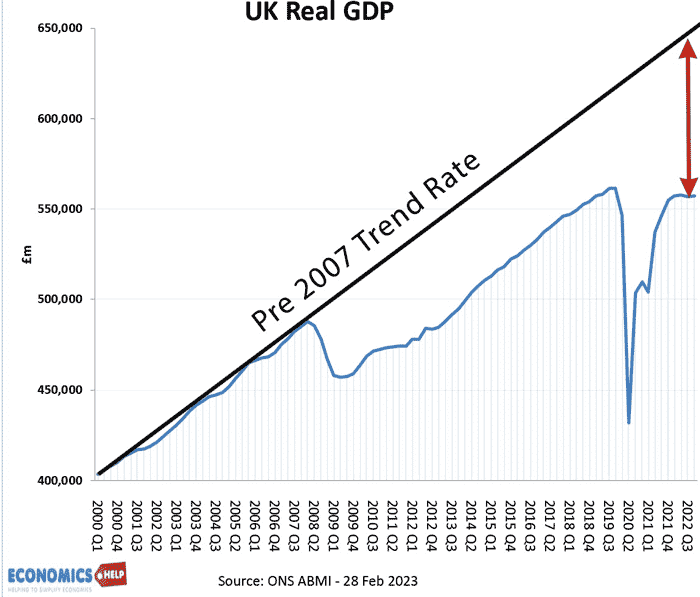

In response to the dire conditions, the Bank of England cut interest rates to record lows of 0.5% in a bid to stimulate economic activity. However, the depth of the credit crunch, combined with government austerity, meant even interest rates of 0.5% failed to return the economy to normal growth.

The Bank were so worried they embarked on quantitative easing. Between 2009 and 2019, the Bank of England injected £425 billion– about 22% of GDP – into the UK economy. The aim of quantitative easing is twofold. Increase the money supply to stimulate demand and increase the price of assets in order to reduce bond yields.

But by increasing bank reserves and reducing interest rates, a side-effect of quantitative easing is that it increases the attractiveness of investing in the stock market and assets like the housing market. Between 2009 and 2022, UK house prices soared 83% – remarkable given that real wages stagnated in this period, and inflation was very low. In the past decade, the UK has been much better at growing wealth than income. And from the perspective of buyers, the cost of housing is not really the house price, but the monthly mortgage and after 12 years of ultra low rates, there was understandably a feeling this was the new normal.

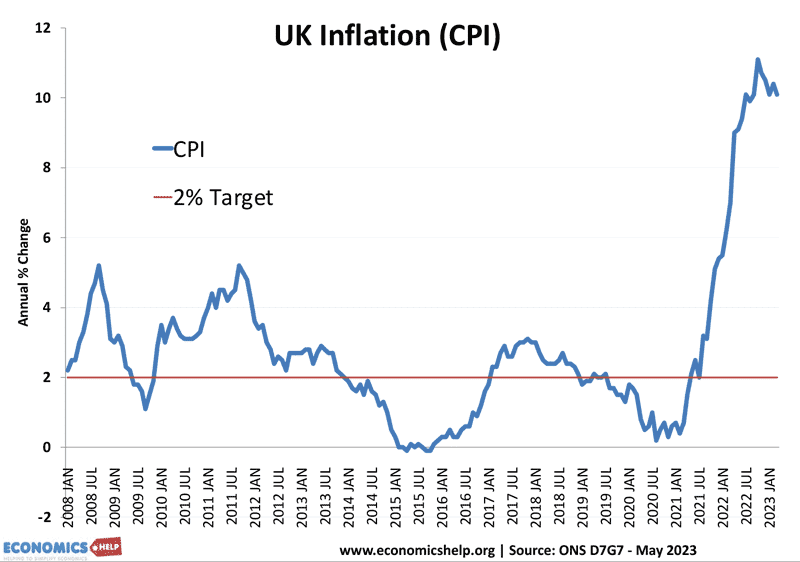

Now doesn’t all this extra QE money create inflation? For 12 years the answer was no, CPI inflation (which ignores house prices) was broadly close to the 2% target. In 2012, the UK had a surge in inflation to 5% (which in those days seemed like a lot). There was pressure for the Bank of England to raise rates, reverse QE and bring inflation under control. But, the Bank of England correctly predicted the inflation was just temporary – primarily from higher taxes and a devaluation in the Pound. Interest rates were kept at 0.5% and inflation soon fell back below target. This is important later for understanding why the Bank got it wrong in 2021.

The 2010s saw low inflation, but strong asset price inflation. It was like a twin track economy, wage growth was very weak, but wealth incresed.

During the Covid crisis of 2020, GDP contracted sharply, the BOE bought an additional £450 billion worth of UK government bonds, bringing the total of QE to £875 billion, or 40% of current GDP. Again interest rates were pushed close to zero and we had another boom in house prices, even as real wages stagnated.

Inflation shocks of 2021/22

But, in late 2021, the global economy had its first inflationary shocks for decades. Covid supply shocks followed by rising oil and gas prices led to a sharp rise in inflation.

Initially, the Bank of England calculated this was like 2008 and 2012 – temporary inflation which would fall soon. However, this didn’t happen; the inflation shock was much greater than 2012. The UK was particularly badly affected by rising oil and gas prices, exacerbated by rising food prices and Brexit shocks to supply chains. In late 2021, the Bank of England belatedly started to raise interest rates from their historical lows.

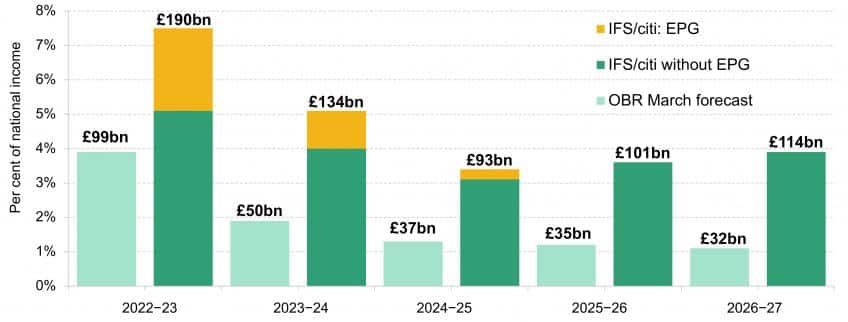

But, then in September 2022, with a backdrop of rising interest rates, high inflation and weak growth, Truss and Kwarteng made a bold bid to boost economic growth, with large tax cuts for business and high earners. Markets were shocked for three reasons.

Firstly, it would cause the government deficit to rise to double to £190bn. Secondly, the stimulus would cause even more inflation and thirdly markets knew it was political disaster to cut taxes for the rich in a cost of living crisis. Bond yields soared because the budget promoted more inflation and with rising interest rates markets had concerns about government debt, which hadn’t surfaced for many years

When Sunak reversed the disastrous budget, interest rates fell close to the pre-September crisis peak, a degree of calm returned. At the start of the year The Bank of England were forecasting inflation would fall back to target of 2% by early 2024. With this kind of forecast, it looked like interest rates may soon be able to peak, and the mortgage crisis may not be so bad.

Persistent Inflation

But, the problem is that inflation has yet again turned out to be much higher and more stubborn than expected. Whilst US inflation has fallen to 4%, the UK has one of the highest inflation rates in the developed world.

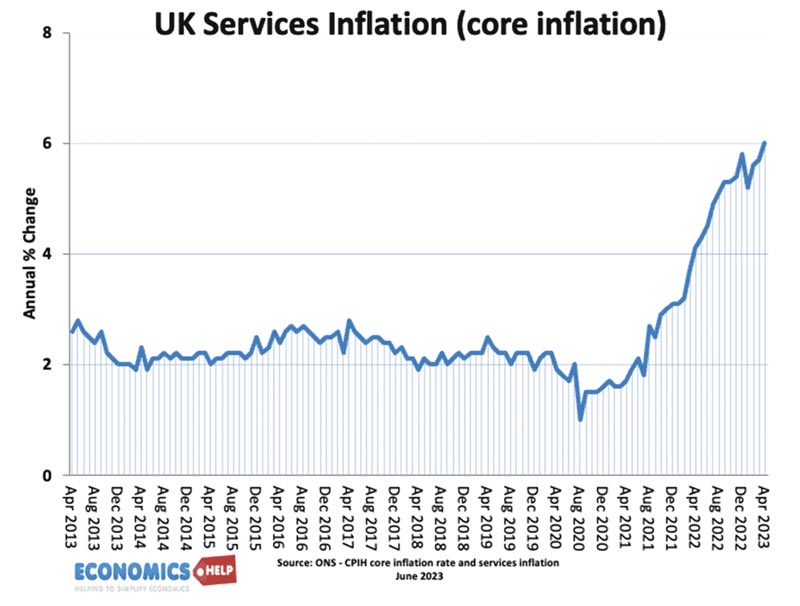

Despite falling oil prices, UK inflation has persistently exceeded the forecasts of economists. Inflation is no longer just due to higher energy and import prices, inflation has become embedded. Services inflation is a good measure of domestic inflation and an indication that underlying core UK inflation is rising. Belatedly nominal wages are rising in a bid to try and keep up with inflation.

This raft of bad news on inflation was the trigger for the current rise in mortgage rates. The difference between the mortgage rates and the base rate has shot up, which means current mortgage deals are more profitable for banks. In the short-term you could say it is profiteering. But, banks may argue they are raising rates because they expect significantly higher base rates in the future. The Resolution Foundation say base interest rates may have to rise to 6%. Mark Carney warns they may remain elevated for a considerable time. Also, there are perhaps other things going on. In the past few weeks, there has been a sea-change in attitudes to house prices. There is an increased awareness house prices are overvalued and the interest rate shock is a potential tipping point, for big falls in house prices. This shift in attitudes is important. Buyers know they can get a big discount on the asking prices and even estate agents are advising clients to be more realistic on prices.

Given this very realistic prospect of falling house prices, banks will be more circumspect in lending to homeowners who could struggle with high mortgage costs and potentially negative equity.

Role of QE

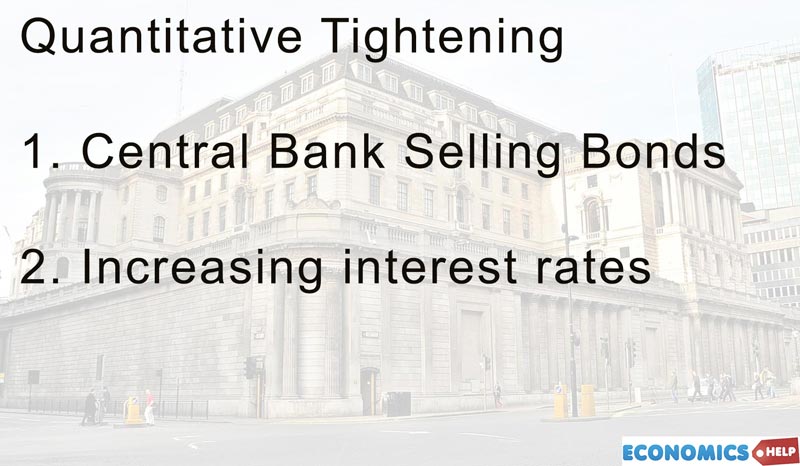

And what about the role of quantitative easing in all this? In November 2022, the Bank of England began the process of quantitative tightening, selling off the government bonds it bought. This has the opposite effect to quantitative easing. Selling bonds reduces asset prices, and pushes up interest rates. In November it sold £0.75bn out of £838bn. A drop in the ocean of its current reserves. But, this is the great unknown of QE, what happens when you reverse it? It is an additional concern for banks.

One feature of QE is that the increased bank reserves, we currently have aim to provide greater financial stability. But, the large reserves of banks are less abundant than they may seem. They have adjusted to new normal of low-interest rates and high reserves by taking more risks. More risk after all was kind of the point of QE. It’s perhaps not as bad as the sub-prime mortgage days of pre-2008, but bad loans and defaults are increasing. For example, Silicon Bank had a great business model if interest rates stayed very low, but the sudden rise in rates caused it to become unprofitable and go bust.

The truth is it is hard to predict the effect of QE on the economy because with Japan, this scale of money creation has not happened before. QE does create uncertainty because there is no certainty how banks will respond to the increase in money supply.

A final complication of QE, is that when interest rates are very low, Central Banks were effectively making profit, but now interest rates have risen, they are paying more interest to commercial banks, government borrowing has become more expensive.

Does new mortgage crisis suggest Trussonomics was correct?

Does the current surge in mortgage rates prove Liz Truss right after all? In a word. No. Basically, if we had Truss/Kwarteng economics on top of the current inflation statistics, there would be even more upward pressure on inflation, interest rates and the selling of sterling. The crisis would just be more severe. You can’t solve the current mortgage and housing crisis by large unfunded tax cuts.

Any glimmers of hope?

On a more positive note, It is worth pointing out that the mortgage market is currently volatile, if we see better than expected inflation statistics later in the year, the outlook could change for the better. (Though Today’s May inflation CPI=8.7% – again was higher than expected) Inflation is forecast to fall with falling food inflation and lower petrol prices. Also, due to time lags, the higher interest rates will increasingly work in slowing down the economy, and therefore, slowing inflation. The Bank of England’s own stress tests from 2022 suggest interest rates of 6% will be unsustainable for the economy. Therefore, there is hope the current fear of permanently rising interest rates may be overplayed. But, even if interest rates were to peak at 5 or 5.5% that is still going to be very costly for many homeowners and the economy.

Related