Last year, the Bank of England made a very gloomy prediction for the UK economy – a deep and prolonged recession.

They were wrong, the UK avoided recession and grew more strongly than some expected, but the downside is that the Bank of England were also wrong about their inflation predictions.

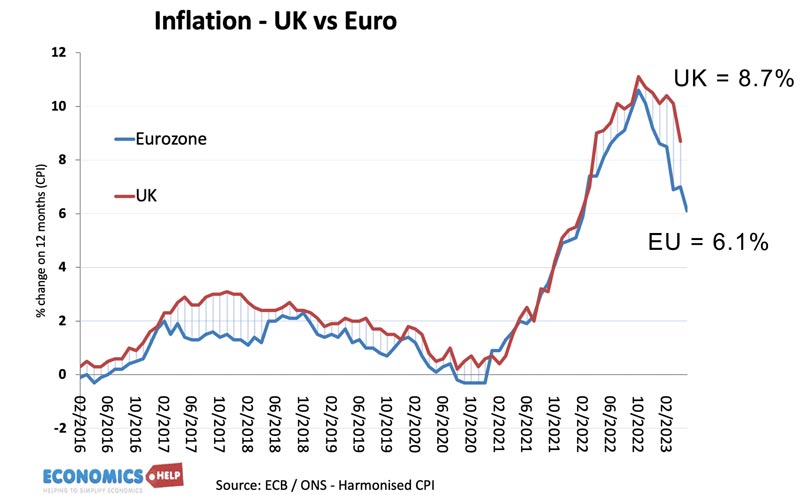

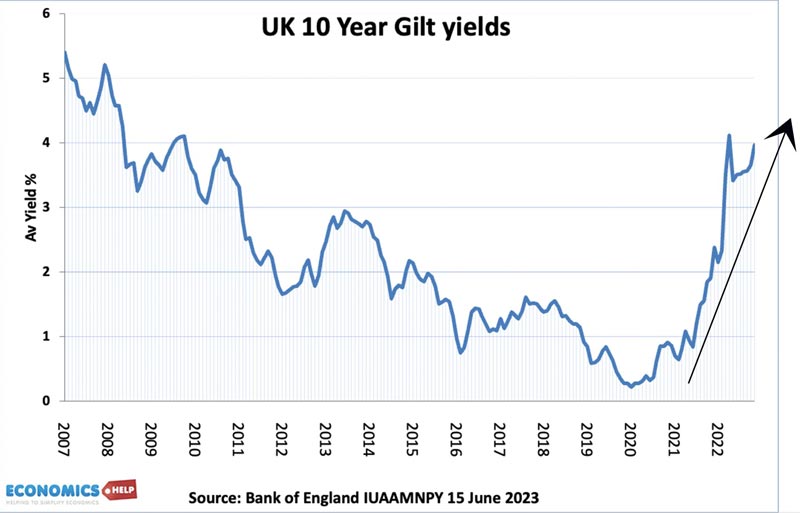

The UK now has one of the highest rates of inflation in the developed world, and this is causing the Bank of England to belatedly increase interest rates in a bid to cool inflation. But, this rapid rise in interest rates risks causing widespread economic pain. The combination of high inflation, falling real wages and a sharp rise in mortgage rates could belatedly push the UK economy into recession by the election year of 2024. Why is the UK economy on a knife-edge, why is inflation in the UK so high and how likely is a deep recession in the UK?

Why is inflation so high?

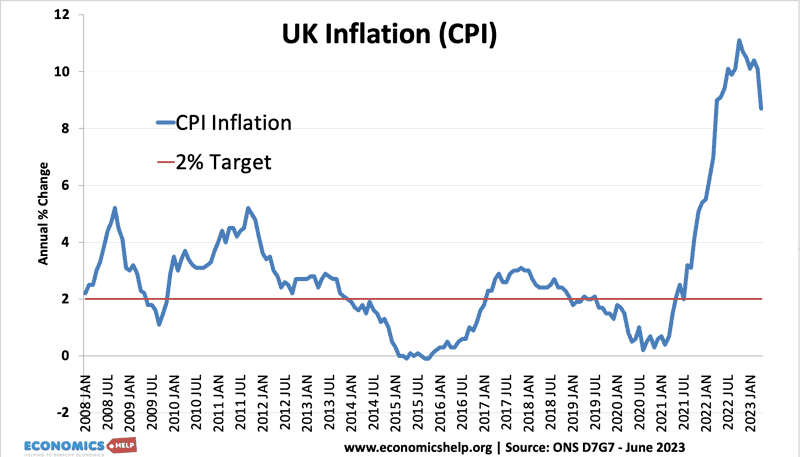

In the past two years, UK inflation has persistently exceeded the Bank of England’s forecast. This was initially due to rising energy and gas prices. But this temporary cost-push inflation has also had second round effects in pushing up nominal wages and also core inflation.

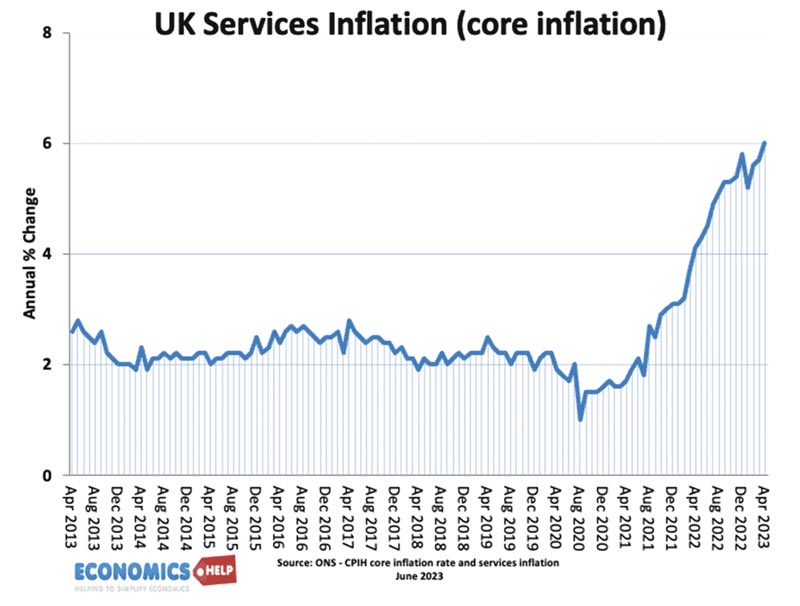

This shows services inflation and this is important because it excludes imports, food and energy and is a sign the UK is generating its own domestically induced inflation. This is what is worrying markets and the Bank of England. Last month the headline rate of inflation dropped to 8.7%, but this fall was less than expected and caused markets to expect interest rates to rise much faster than before.

Impact of Higher interest rates

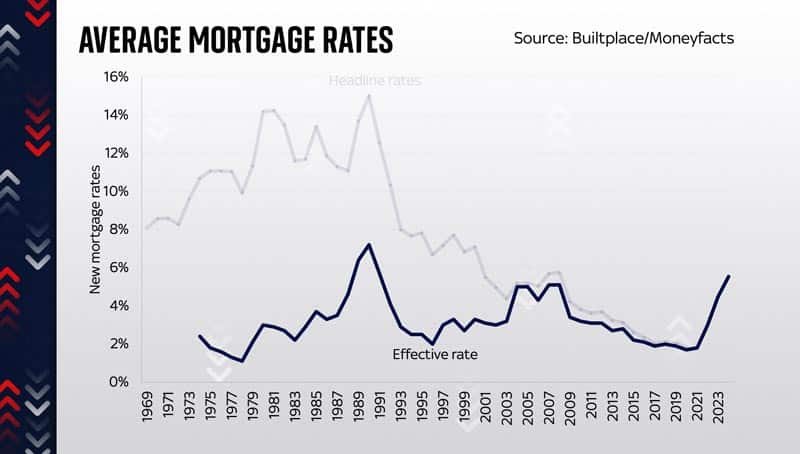

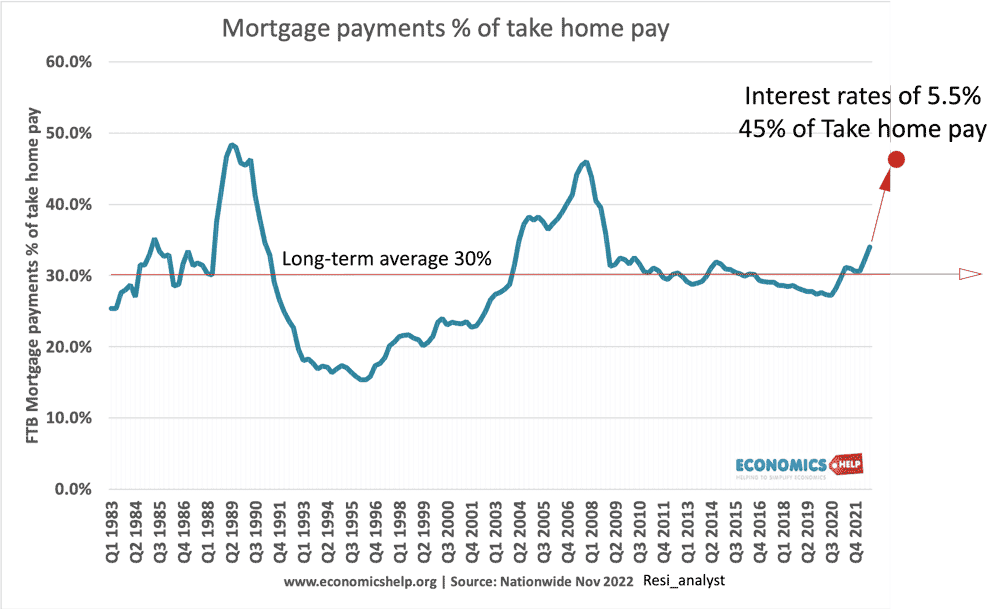

And the rise in interest rates will have a really big effect on the economy, especially as over 1 million homeowners will soon remortgage to a new rate. In 2021, fixed rate mortgage rates were as low as 2%. If they rise to 6%, that will cause a large jump in mortgage costs. Even on a modest £200,000 mortgage, the average homeowner could face an extra £440 a month. Very difficult, in a time of falling real wages.

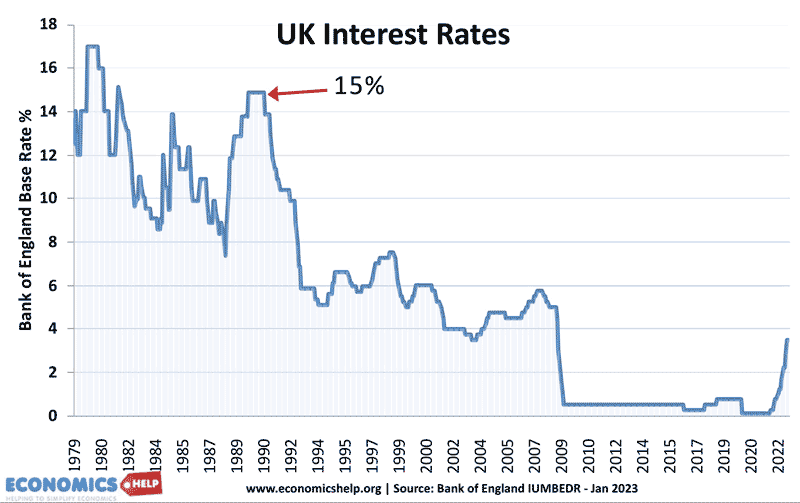

Historically, a headline rate of 5% may not sound much. The Daily Telegraph ran a piece yesterday on how its old readers survived interest rates of 15% in the 1970s, but these headline rates are misleading.

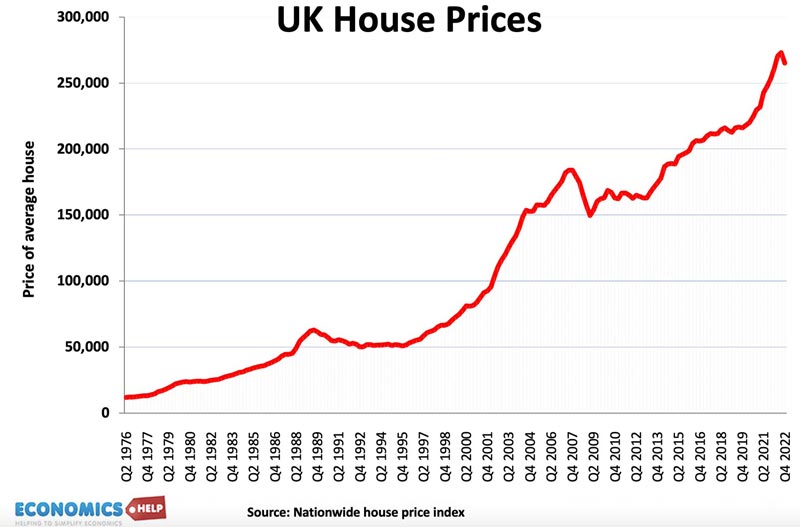

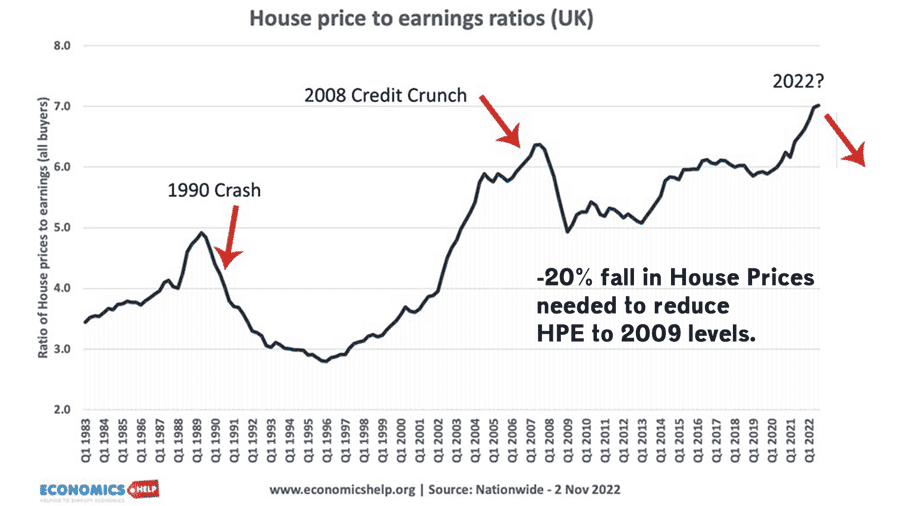

House prices were much lower in the 1970s. Because house price to income ratios are so high today, a small increase in interest rates has very significant effect.

This graph shows the effective interest rate and why a headline rate of 15% in 1979 was equivalent to 3% now. More importantly, it shows that effective interest rates are now close to the level of the early 1990s, when they caused a deep recession and big housing price crash.

Usually with rising interest rates there is a time lag of around 18 months before their effect is fully felt. Interest rates started rising last year, so it will only be in 2024 that their impact will be fully felt on the economy. Interest rates have a time lag because many are on short-term mortgage deals and it takes time for banks and mortgage holders to adjust.

How effective are higher rates in reducing inflation?

Another problem with interest rates is that they are a very imperfect tool for bringing inflation down. The past 12 rate increases have done very little to reduce inflation. The UK’s inflation is not because the economy is booming like say in the late 1980s but because we have all kinds of new supply constraints and rising prices of food and energy.

Firstly, the labour market is very tight, vacancies reached a record 1.3 million in 2022. The result is higher costs for firms and upward pressure on nominal wages. The labour market has been hit by Brexit with some firms struggling to fill vacancies previously filled by EU migrants. Secondly, Brexit has also made it more difficult to import cheap food. Earlier in the year, the UK faced shortages, which was not seen elsewhere on the continent.

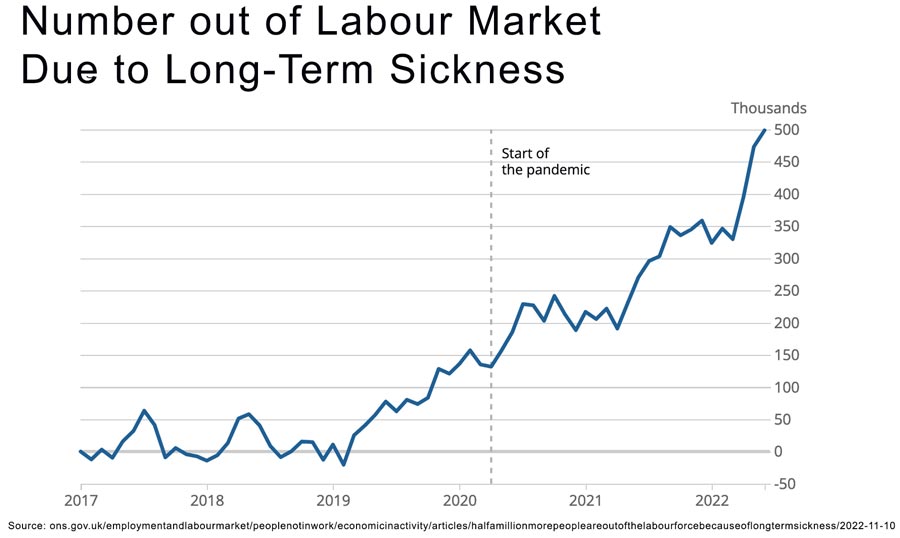

Another very big problem is that the UK has seen a rise in long-term sickness which has caused a fall in labour market participation. This explains why the labour market is tight, yet economic growth is very low. Wages aren’t being pushed up by red-hot demand, but by high inflation combined with a shortage of workers and high vacancies.

The problem is that raising interest rates doesn’t tackle these underlying supply constraints. Therefore to bring inflation down to target of 2%, may require very substantial economic pain, which will cause a recession. Jeremy Hunt recently said he would be happy to have a recession to bring down inflation, but that is the problem, with inflation so stubborn it will require a recession to bring back to target.

The second problem of raising interest rates is that it affects different people in different ways. Some actually benefit from higher interest rates; savers will see much better returns and increased interest income. Older people who have paid off their mortgageswill be blissfully unaffected by rising interest rates. The point is that to bring UK’s inflation down through interest rates is likely to be a painful process. A process that will cause the most pain to homeowners and mortgage holders. It may also be bad news for renters who already dealing with record rents. Higher interest rates are causing landlords to sell homes reducing supply or pass on interest costs to renters.

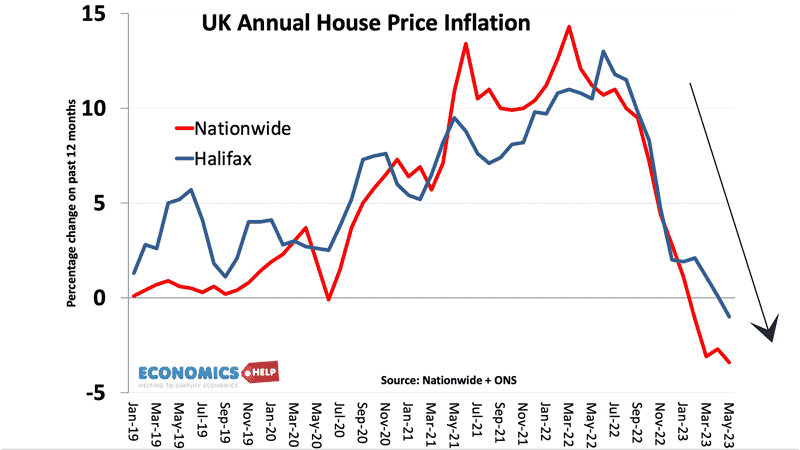

The increased mortgage costs will also put pressure on house prices. Last year, prices reached historical highs of unaffordability.

The combination of overvalued prices and rising mortgage rates is a recipe for falling prices. Moody’s predict a 10% fall, others say it could be a crash of up to 35%. But, the important thing is that falling house prices will, at least in the short term, cause lower economic growth. In the past decade, rising house prices have helped underpin household confidence and are a source of equity withdrawal. But, when prices fall, it causes a negative wealth effect – a loss of confidence, and the spectre of negative equity. The last two periods of house price fall 1991 and 2009 both coincided with a deep recession. A recession contributes to falling house prices, but falling house prices also fuel recessionary pressures.

Other negative pressures

Not only do we have the biggest interest rate squeeze since 1991, but there are many other unfavourable factors hurting the UK economy.

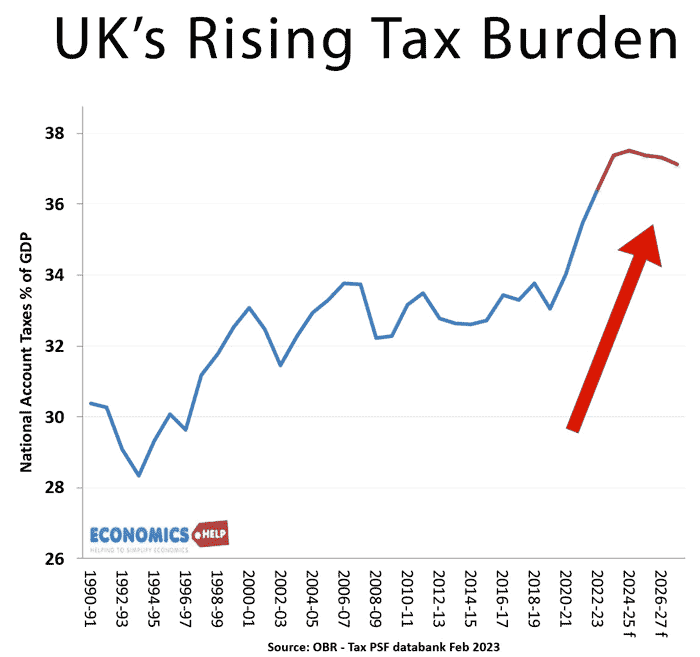

Recent tax changes led to the highest tax burden as a share of GDP. High inflation and rising nominal wages is causing increasing numbers of workers to move into the higher tax bracket of 40%. It is a shock when wages go, up but you realise the extra income is taxed at 40% rather than 20%.

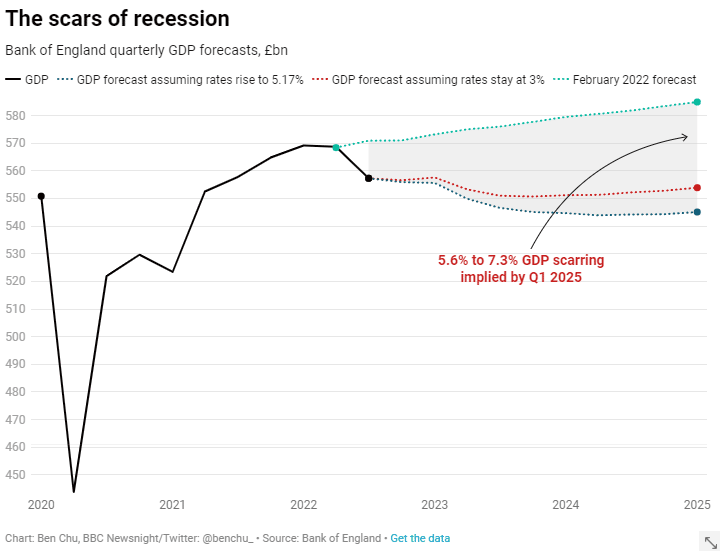

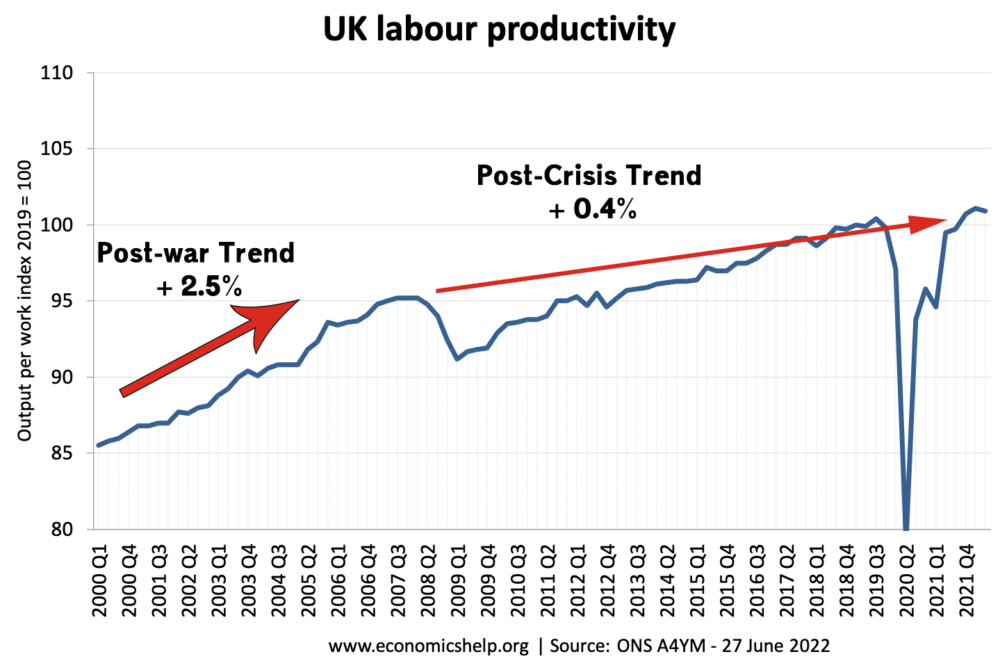

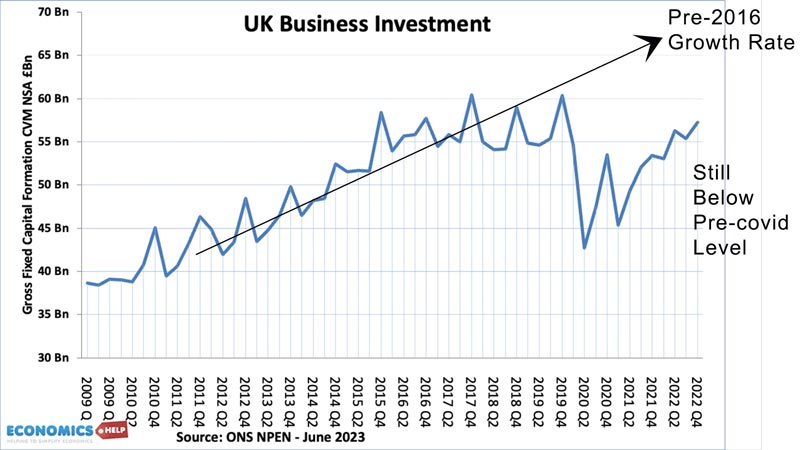

Another problem for the UK economy is that underlying long-term growth has been very weak since 2009. This weak economic growth means that even a small headwind like higher rates can push the economy into recession. There is little resilience. This shows how UK productivity growth changed after 2009. It has led to an unprecedented fall in rates of economic growth. It also shows the lost output from below-trend economic growth. The impact of Brexit costs, uncertainty and poor productivity have all led to low business investment, which is crucial for long-term growth.

Although there has been some recovery since Covid, it is still below the 2020 peak and the new era of higher interest rates will also hit business investment as the cost of borrowing hits them too.

Fiscal policy to the rescue?

Given the Bank is tightening monetary policy, one option is for the government to provide some fiscal stimulus, for example, the tax cuts Conservative MPs long for. There has already been some noise about providing help for mortgage owners. However, the room for fiscal manoeuvre is limited by rising debt levels and also rising interest rate costs.

The impact of last September, when bond yields soared will be fresh in the government’s mind, a reminder that uncosted tax cuts could be disastrous in an era of rising interest rates and low growth. The economist notes that

“For every one-percentage-point rise in rates, the British government’s debt-service costs rise by 0.5% of GDP within a year. ” (Fiscal Policy)

But, also even a small cut in income tax would be insufficient to boost incomes to offset the impact of rising mortgage rates.

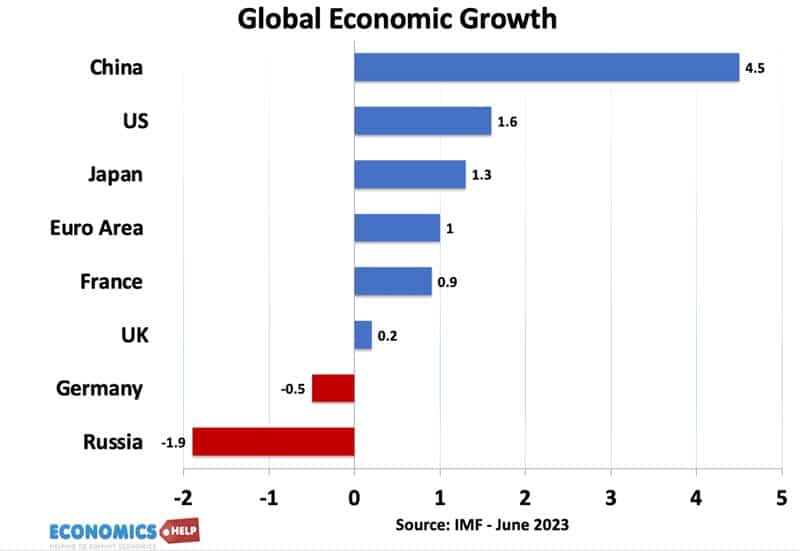

Across the globe there are also signs of a global slowdown, which will hurt the UK economy, which despite Brexit is still a relatively open economy, reliant on trade and global financial flows. The usually strong German economy contracted 0.5% in the first quarter of 2023. This was mainly due to a decline in consumer spending in response to higher prices. Yet, the ECB recently raised interest rates to tackle stubborn EU inflation too. The Chinese economy is also struggling due to a bust in the property sector. But, also of more concern is much weaker exports, hinting at weakness in global demand.

Any room for optimism?

It’s easy to be pessimistic about the state of the UK economy. The rise in interest rates and the prospect of falling house prices are definitely very real problems affecting the economy right now. If we try to end on a more optimistic note, inflation is still set to fall towards the end of the year, helped by falling petrol and energy prices. The effect of previous interest rate rises have not been fully felt and once they do start to reduce spending, the fall in inflation could be accelerated. This will hopefully reduce pressure on increasing rates. The mortgage market is currently highly volatile, but if the next inflation figures were better than expected, sentiment on rates could change. This may sound like clutching at straws, but it may prove interest rates of 5-6% are unsustainable given so many have become accustomed to low rates. But, whatever happens, to demand, it doesn’t alter the long-term problems of low investment and low productivity, which will not be helped by the current problems.