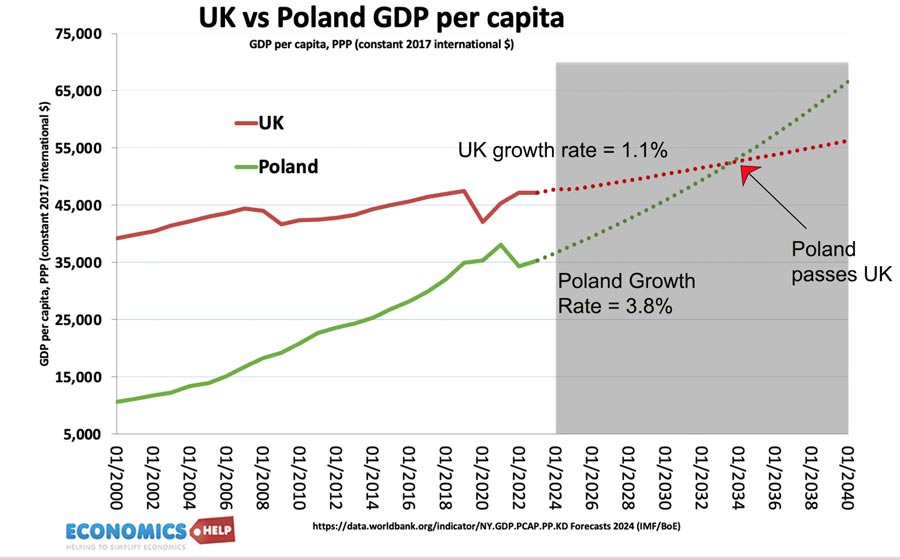

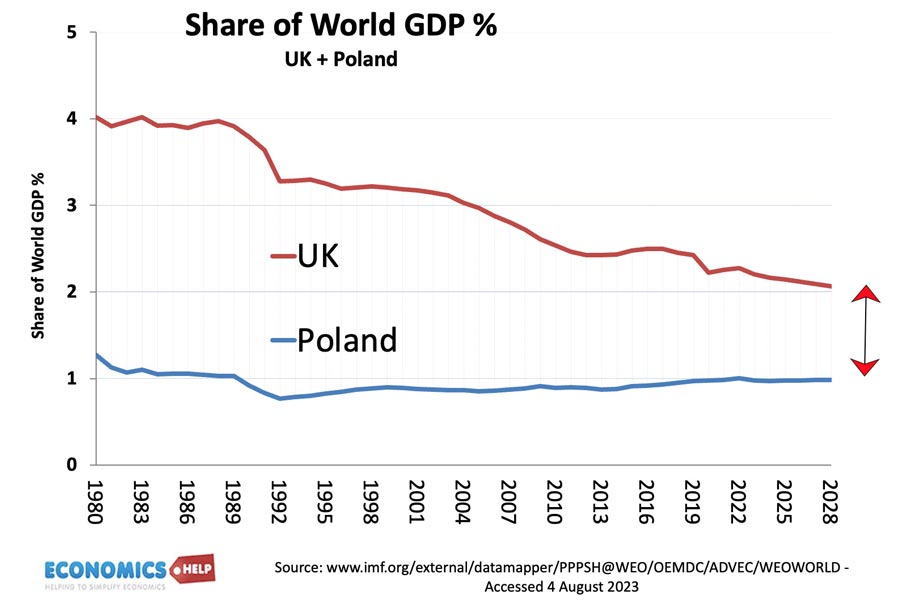

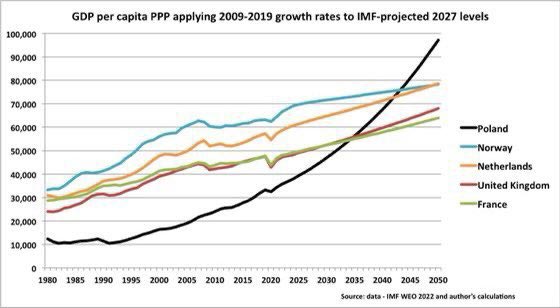

In 2000, the average GDP per capita in the UK was over three times that of Poland. But with the UK economy stuck in a trap of low economic growth, forecasts suggest, on current growth trends Poland could overtake the UK economy by 2035.

In terms of raw size, the UK will still be larger, but measured by average incomes Poland could overtake.

In the early 2000s nearly 1 million Polish workers came to the UK attracted by higher real wages, but within a decade, this could be reversed. What explains this remarkable turn-around?

Poland’s Success

Firstly, it reflects good news. Eastern European economies, such as Poland have been successful in catching up with Western Europe. It is worth bearing in mind, after the lost decades of Communism there were some relatively easy gains in productivity by changing the inefficiency of state intervention.

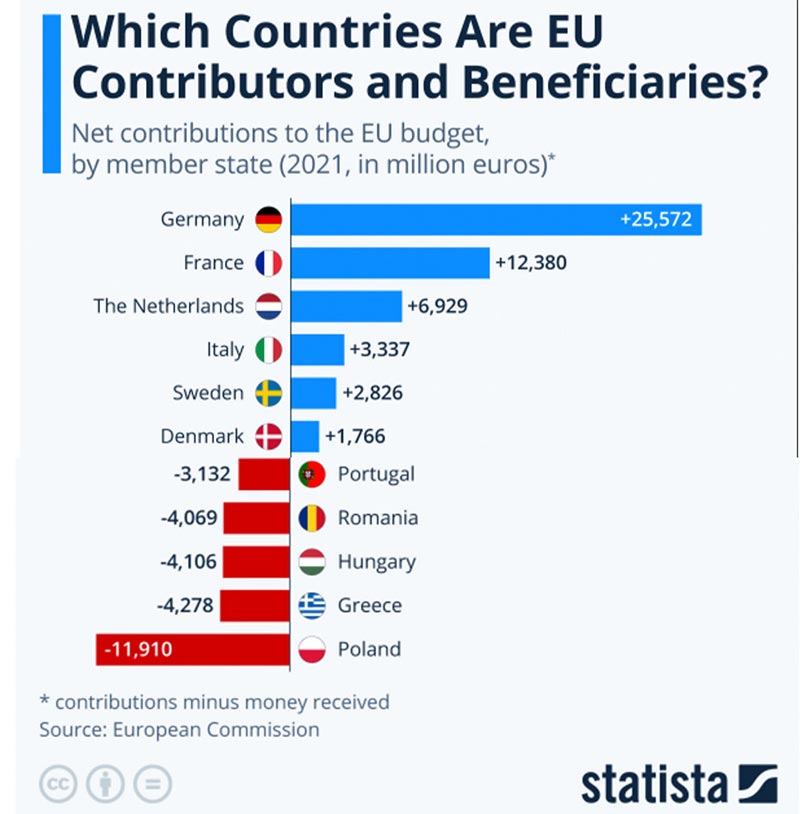

Another reason for Poland’s remarkable growth is that it has been successful in attracting foreign capital to transform industry and become a key player in global supply chains. It is also benefiting from a desire to reduce reliance on China and bring manufacturing closer to Europe. Poland’s success can be best seen in the motor industry, where it has been able to compete not just on low wages, but increasingly through adding greater value and being able to produce high-tech batteries and engines. Poland’s transformation has also been helped by receiving the biggest net contributions from the EU budget. In 2021, it received over £11 billion.

We should bear in mind, this prediction is based on maintaining growth of 3.8%. Things could change. For example, access to EU funds could be curtailed by political interference in the courts. Poland is also heavily dependent on the German economy with 28% of exports going to its neighbour and as the German economy slows, it will impact Poland. Poland has also been quite dependent on Russian gas. Poland has also recently absorbed 1.5 million Ukrainian immigrants, who will provide a boost to real GDP, though not necessarily real GDP per capita.

Failures of the UK Economy

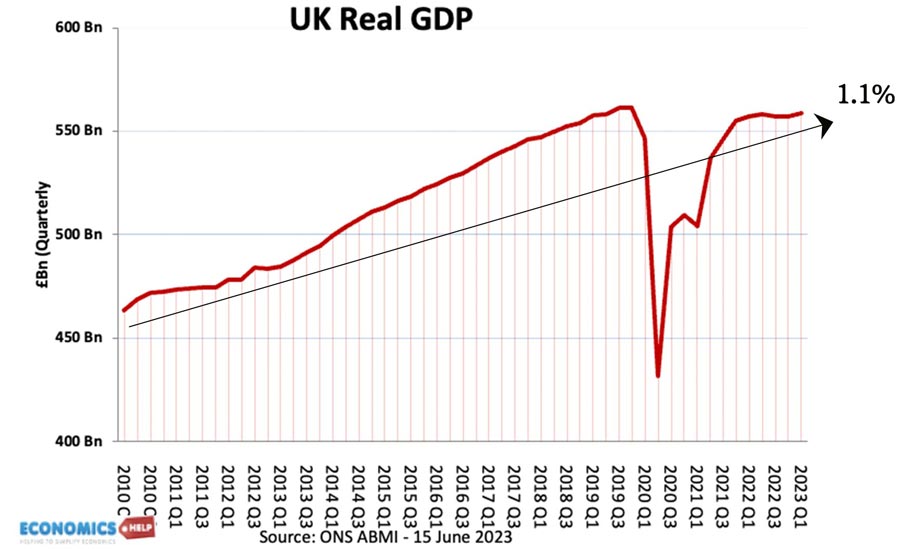

But, whatever challenges the Polish economy faces, the UK can only dream of a growth rate of anything like 3.8%.

Since 2009, UK growth has averaged 1.1% and after seeing the latest Bank of England’s forecasts, even this forecast could prove optimistic for the future.

North Sea Oil Decline

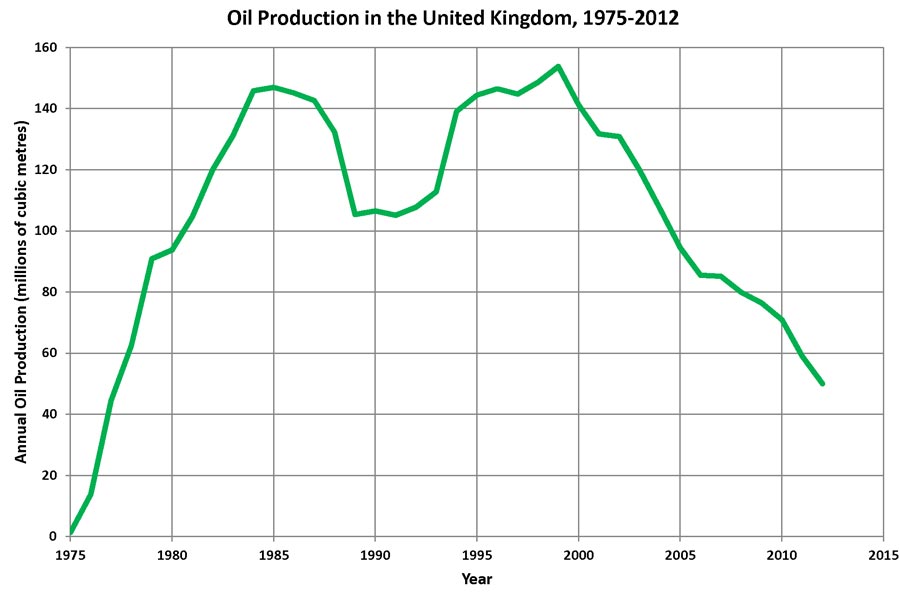

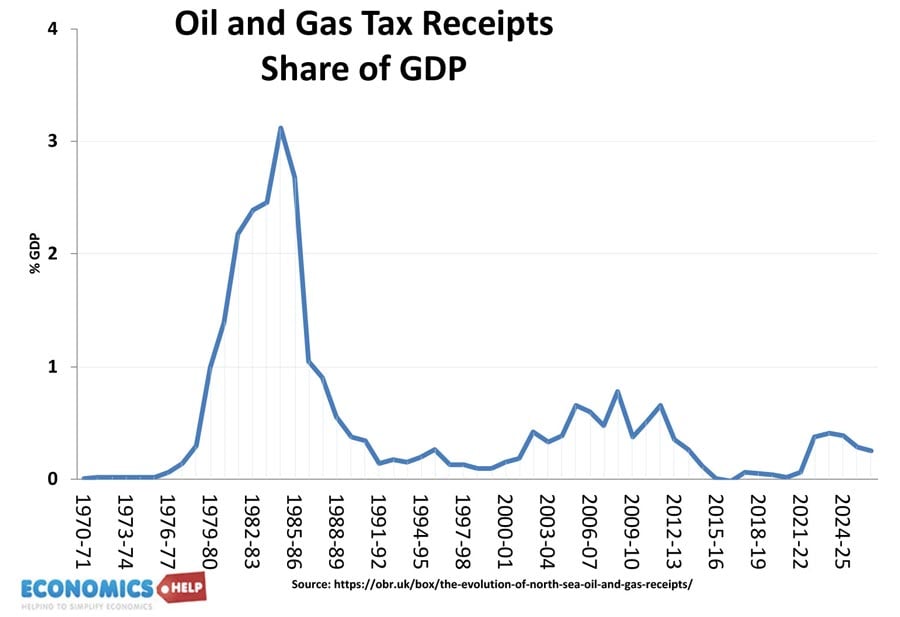

The recent malaise of the UK economy has several causes but if we go back to the 1980s and 1990s, North Sea Oil was an important source of growth, raising tax revenues and a focus for research and development. In the 1980s, high prices and high output led to a North Sea Oil tax bonanza.

This led to a surge in the value of the Pound which made other exports less competitive. The UK had a mild case of Dutch Disease with the oil industry crowding out the rest of the economy.

Also, if we compare the UK with Norway, the UK oil bonanza of the 1980s was largely used to fund income tax cuts, with no long-term plan such as Norway’s Government Pension Fund.

But, since the early 2000s, UK output has dramatically fallen. Rishi Sunak’s recent promise to increase output from the North Sea is more symbolic than practical. There just isn’t much oil left to extract.

Finance Sector

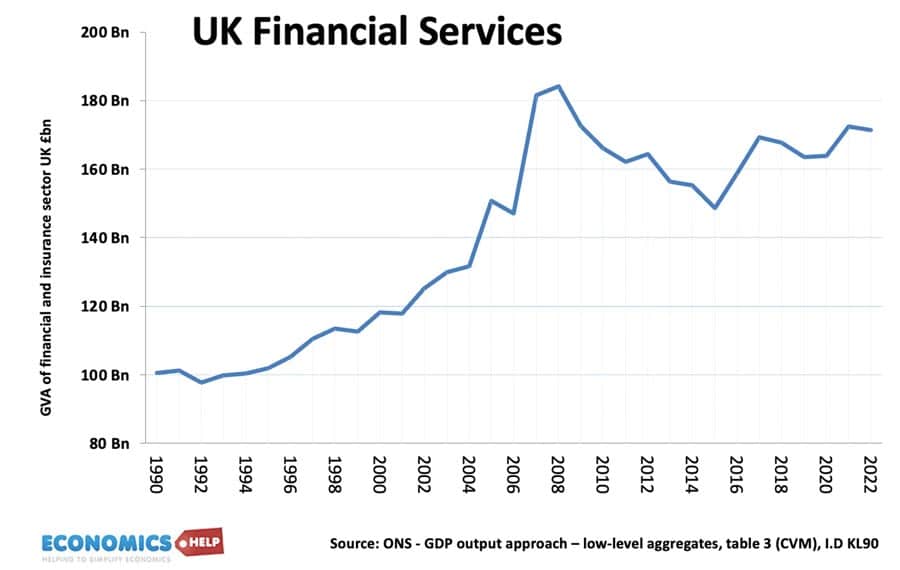

In the 1990s and 2000s, the UK economy was bolstered by the growth of finance. The Big Bang of the late 1980s, saw London become one of the most deregulated financial markets and a main centre of global finance. London benefitted from the rush of new financial instruments such as derivatives and credit default swaps.

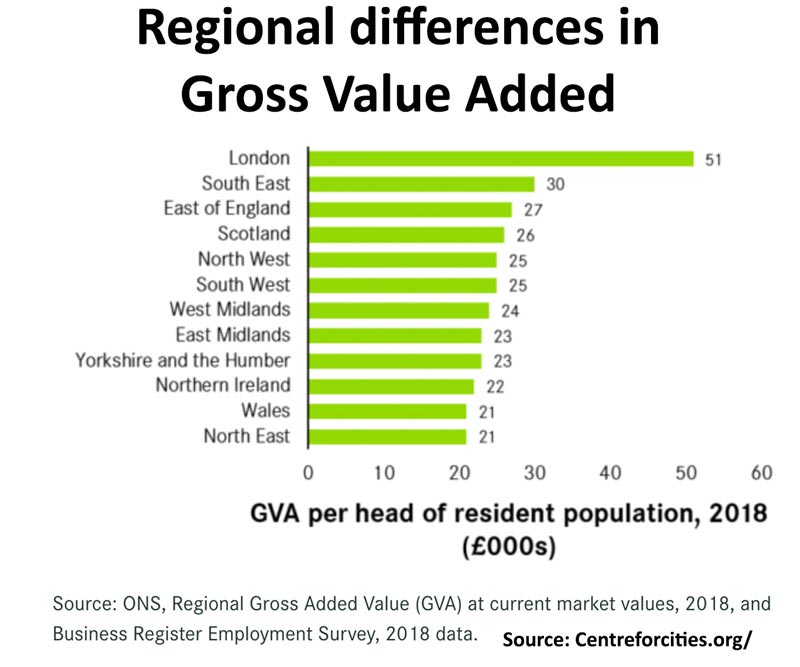

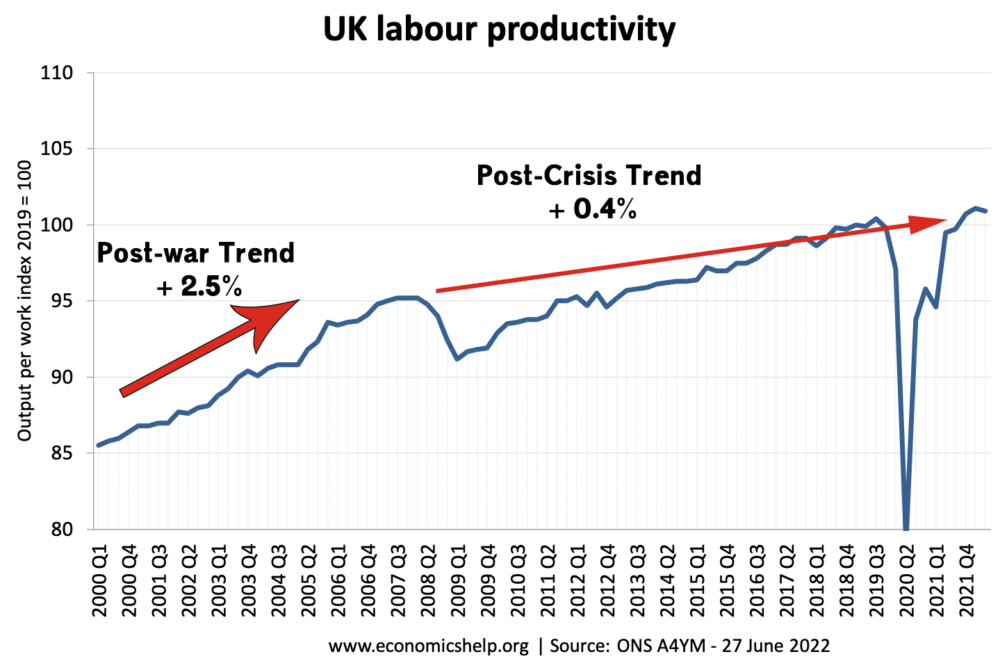

But the success of London as a global financial centre made the UK economy reliant on both finance and the city of London. When the financial crisis hit the global economy in 2008, London was particularly exposed, the rapid growth in finance went into decline and a major source of income and tax revenue fell for several years. It was no-coincidence that after 2008 the UK started to see the big fall in productivity. Before 2008, growth was good, but after 2008, growth has been anaemic.

In 2008, due to the impact of the credit crisis the UK experienced a massive 30% devaluation in the currency, which, in theory, should make exports cheaper and boost manufacturing, but industrial output continued to decline and remain weak.

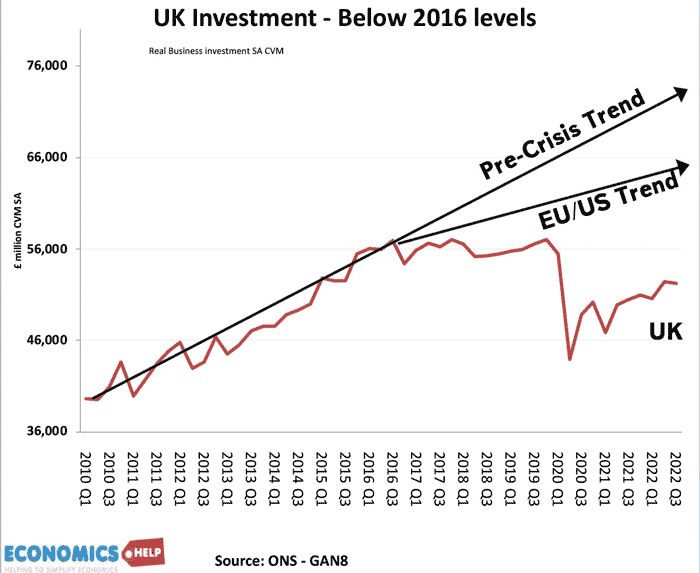

Throughout the 2010s, investment was poor, further hit hard by Brexit in 2016. It left the UK with one of the lowest levels of investment in the OECD. The problem with a strong oil and finance sector is that it can minimise investment and growth elsewhere in the economy – a kind of crowding out effect. However, whilst this is part of the long-term puzzle, we shouldn’t overstate their role.

Austerity of the 2010s

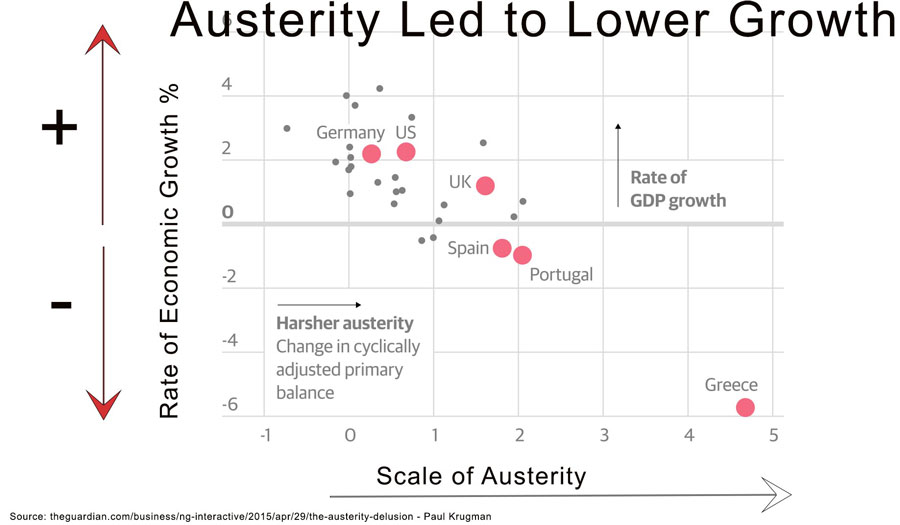

The 2008 recession particularly hit tax revenues because finance with its high salaries paid a significant chunk of income tax. A major feature of the 2010 election was the Conservative plan to reduce debt. This led to the austerity of the 2010s with limited public sector investment and low growth in spending, particularly hitting public sector pay, which has lagged even the poor private sector growth. Austerity magnified the slowdown in economic growth and with interest rates close to zero, it was a missed opportunity for investment in bottlenecks in the UK economy such as housing, transport, and power generation. The unfortunate thing about the 2010s is that ultra-low interest rates did not stimulate capital investment, but investment in property and assets, with wealth growing faster than income.

Brexit

At least two of the reasons for the Brexit vote in 2016, were high levels of immigration from Eastern Europe and the stagnation in wages, which occurred since 2008. It was easy to make a loose association between the two. However, if anything, the nature of Brexit has only added to the UK’s economic problems, with both a significant rise in uncertainty curtailing investment, and new trading rules, making it difficult for British exporters and importers, who now face higher costs and frictions. Ironically, many British firms have moved part of their operations into the EU to escape Brexit red tape. Poland is actively courting British firms. Since 2016, the UK has struggled more than others – with real wage growth amongst the lowest. The negative impact of Brexit is another weight on wage growth.

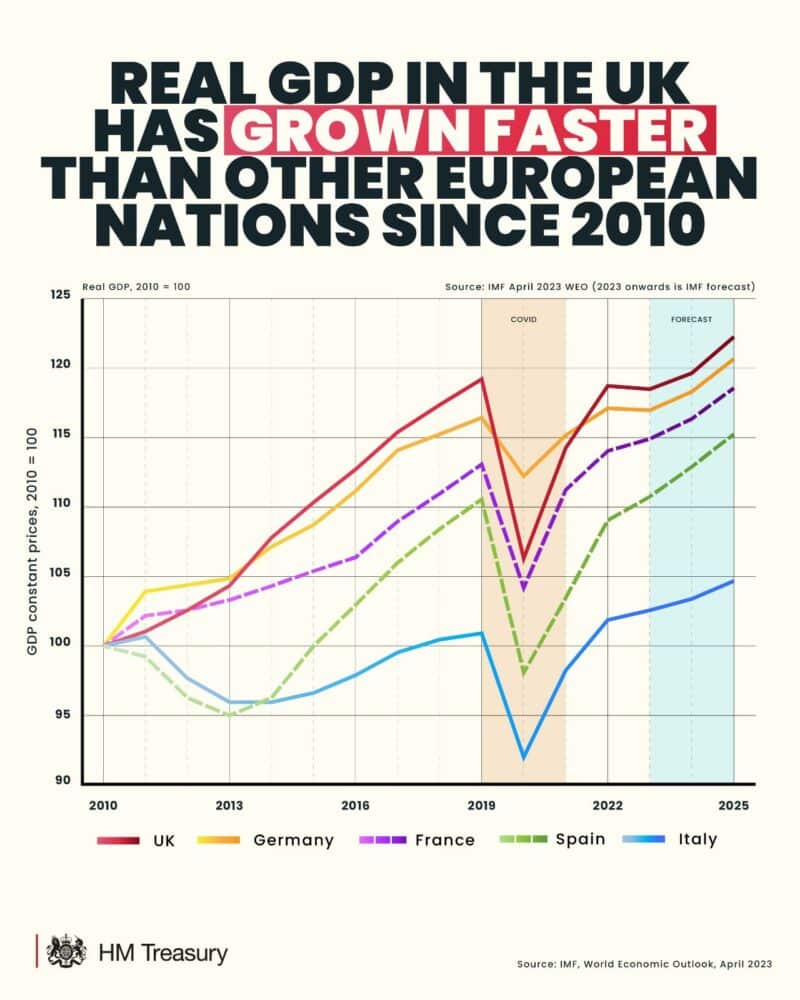

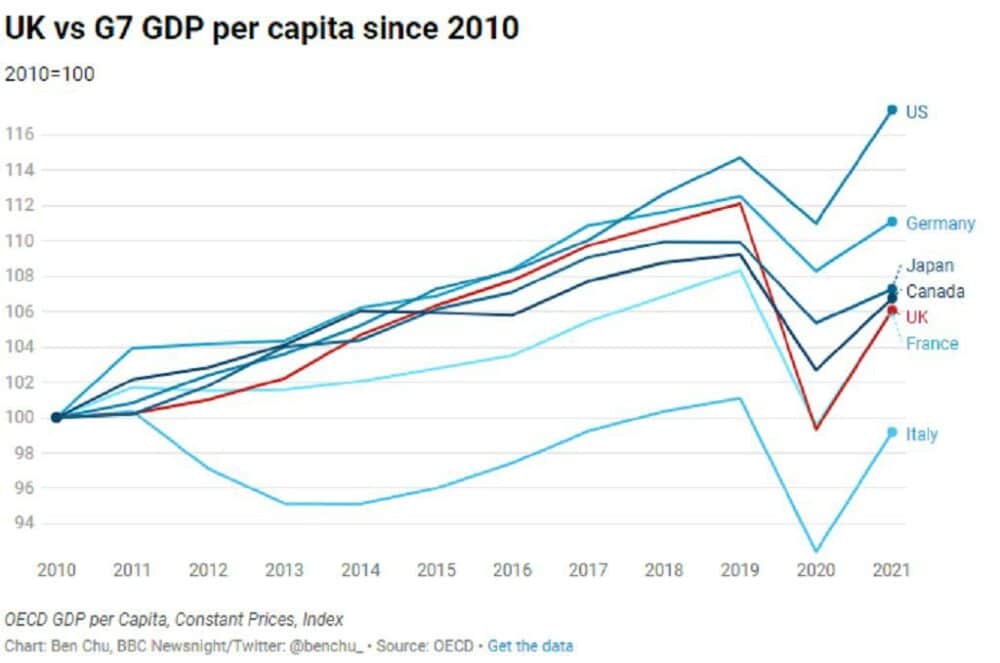

Recently, the chancellor claimed that since 2010 UK economic growth has been the 3rd best in the G7. This is true but needs context. Since 2010, UK real GDP growth has been faster than European economies, helped in no small part by the Euro debt crisis of 2012.

Source: Ben Chu, BBC NewsNight

However, if we adjust for population, the effect is much reduced. In other words, part of UK real GDP growth is due to the rising population. But, for wages, what counts is per capita growth. And if we look at productivity growth (output per worker), then the UK is the worst in the G7. So higher real GDP has been caused by rising population and people working longer hours, not higher real wage rates. Productivity is the key to real wage growth and if productivity is flat, so will real wage growth.

The problem is that with low investment and low confidence there seems to be no immediate solution to the UK’s productivity performance.

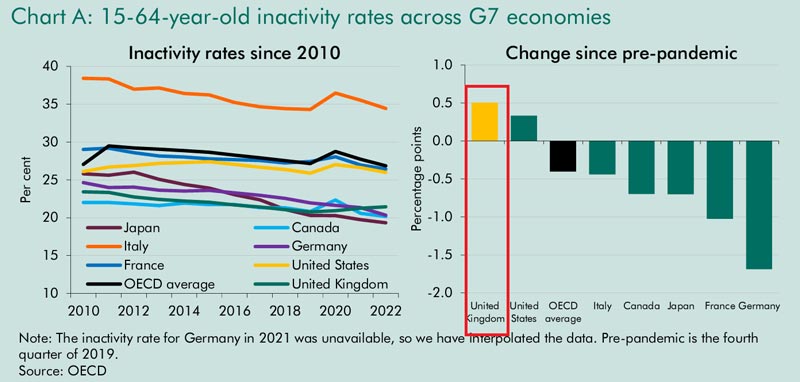

Since the pandemic, the UK has had the largest rise in labour market inactivity, with bad health affecting labour supply and productivity. This is something that has no easy fix.

Is Prediction Really True?

Now, it should be said, the long-term prediction for Poland to over-take the UK wages in 2035 is speculative at best.

For context, on current growth rates, Poland would also overtake several other European countries. Secondly, predicting growth rates for next year is difficult, let alone 10 years in the future. Despite all the real short-term difficulties, the UK could still find a way to break out of its low growth and low productivity and increase economic growth. Similarly, despite the current strength of the Polish economy, it is not guaranted to last. As Poland becomes a mature economy, the scope for easy gains in productivity will be reduced. But, equally, if the UK malaise continues, it could happen even quicker than 2035.

But in the long-term, we would expect a narrowing of wage differentials between similar countries with geographical proximity. And this is a good thing. Economics is not a zero-sum game. The UK benefits from a strong Polish economy. It is an opportunity not a threat.

The UK has definitely had a series of self-inflicted wounds in recent years, which have accelerated the convergence of wages. But, it does lead to interesting outcomes. If Polish and UK wages become similar over time, free movement of labour may seem much more attractive and less of a barrier to rejoining the single market in the future.

Further reading

- Could a new Labour Government Reverse UK Economic Decline?

- How the UK economy has changed in the past 70 years (1952-2022)

This is a pretty shocking info for someone not in the field. I’m currently learning and doing some research to help my students and I’ve learned a lot from your blog