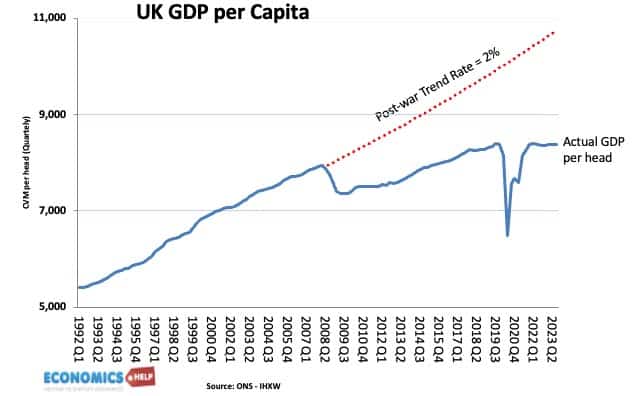

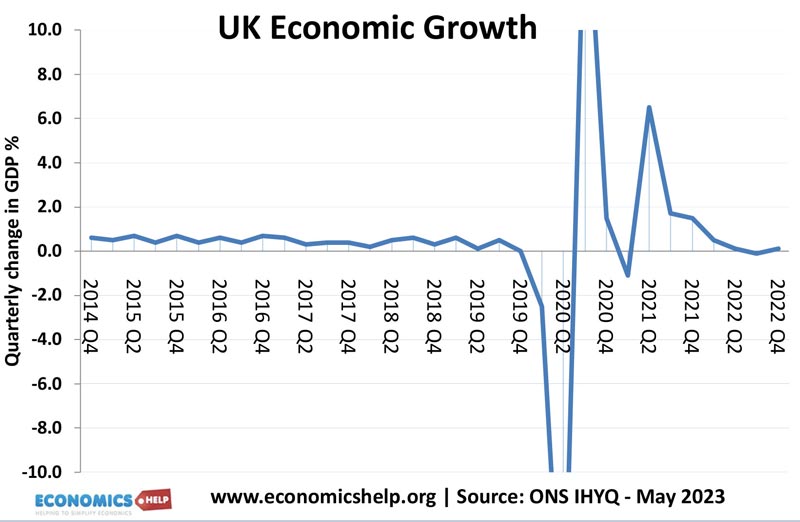

In the post-war period, the UK economy grow at 2.5% a year, but since great financial crisis, growth has slowed down markedly.

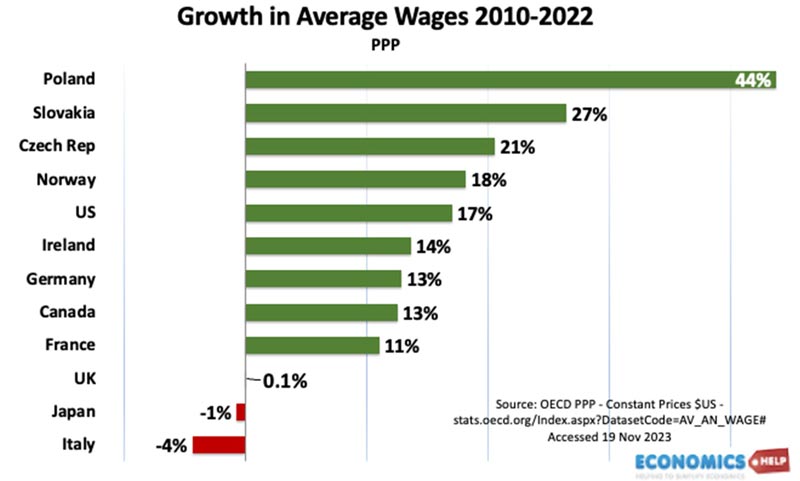

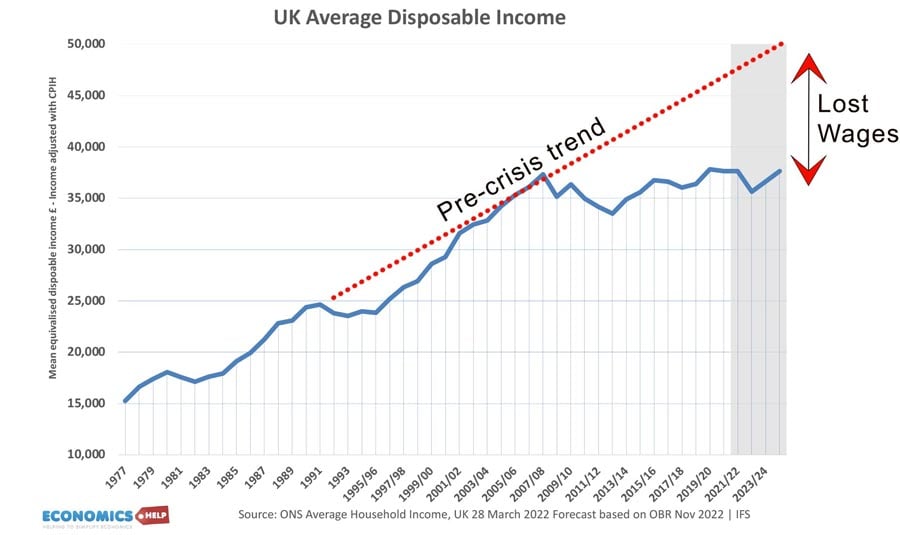

The OECD report that since 2010, the UK has seen growth of just 0.1% in average wages, significantly lower than the majority of our main competitors. If current trends of growth are maintained, Polish living standards could exceed the UK by the late 2030s.

The poor growth record of the UK was the motivation for Liz Truss’ shock therapy approach in September 2022. The problem was that large unfunded tax cuts for high earners sent markets into a spin, pushed up interest rates and damaged confidence. It seems there is no easy solution to economic stagnation. But, If the outlook for the economy has deteriorated how much is due to external factors and how much is due to mismanagement by the government? And importantly can we turn it around?

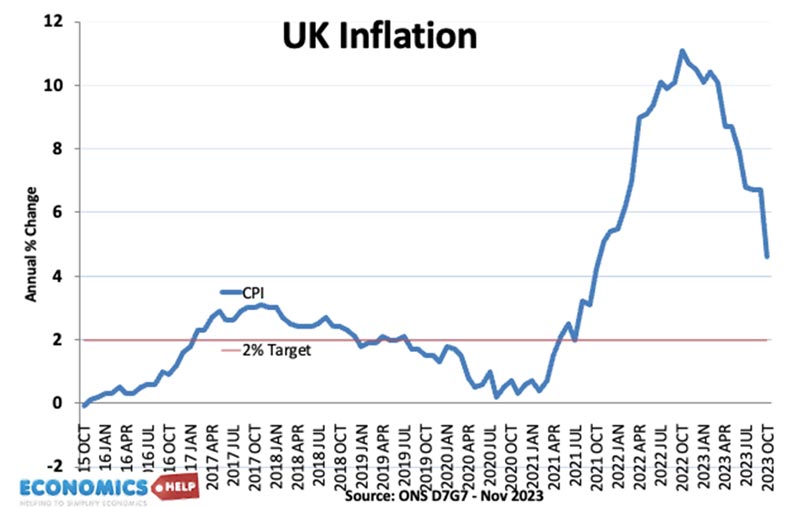

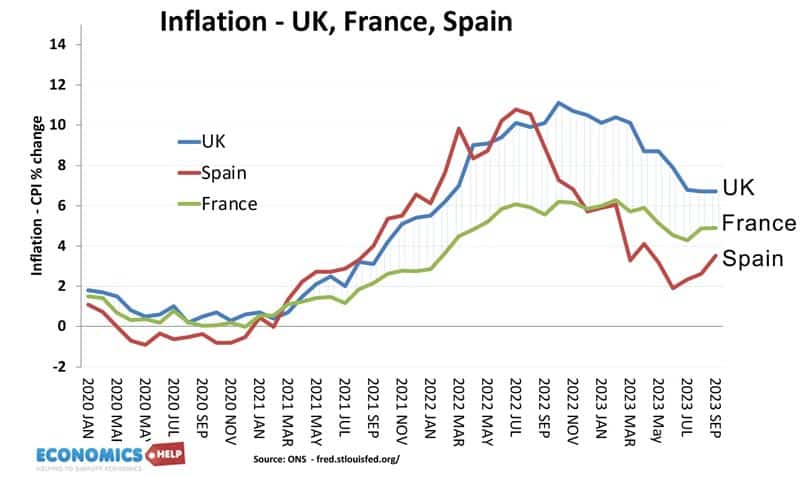

The biggest problem of the past two years has been inflation. It has caused falling real wages, uncertainty, and has impacted the poorest most. Recently, Rishi Sunak claimed credit for halving inflation this year from 10 to 5%. And it is true inflation has fallen, but it has very little to do with government policy. The initial spike in inflation came from a surge in gas and oil prices. In 2022, the Bank of England hoped the rise in inflation would prove temporary, but their forecasts were repeatedly wrong, and inflation grew much faster, and this is why interest rates have had to increase so quickly. The fall in inflation is primarily due to recent declines in energy prices.

With inflation, it seems the government is at the mercy of external factors. But, it is not entirely true. Some European countries such as Spain and France had lower inflation than the UK. The main reason was that in France and Spain, the governments were more willing to intervene in capping energy price increases. This is expensive, but by preventing large energy price rises, it reduced inflation elsewhere in the economy, reducing costs for workers and business.

Causes of Growth Slowdown

If inflation was mainly due to external factors and the Bank of England, what about the slowdown in economic growth since 2010? Back in 2010, the Conservatives inherited an economy recovering from the global credit crunch and a record peace-time budget deficit. A central plan of the Cameron and Osborne era was the necessity of austerity. They argued borrowing needed to be reduced quickly. But, the panic to reduce debt was not shared by most economists.

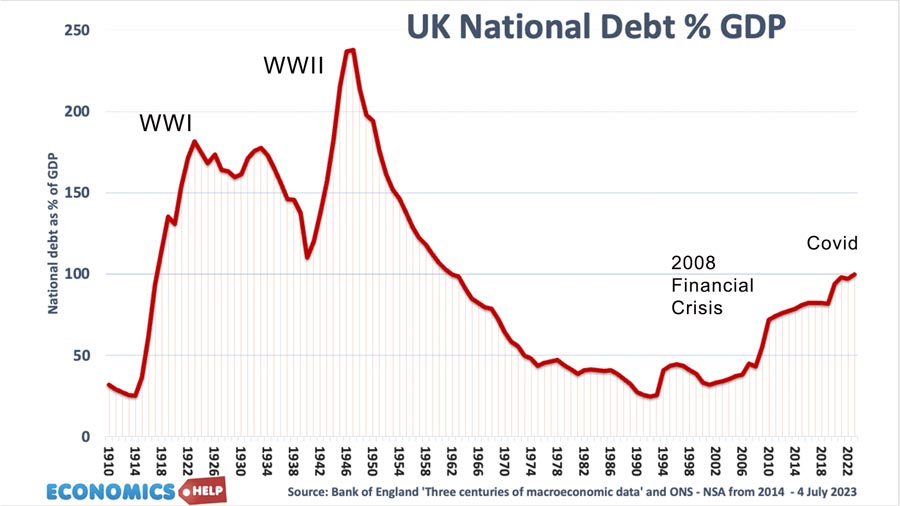

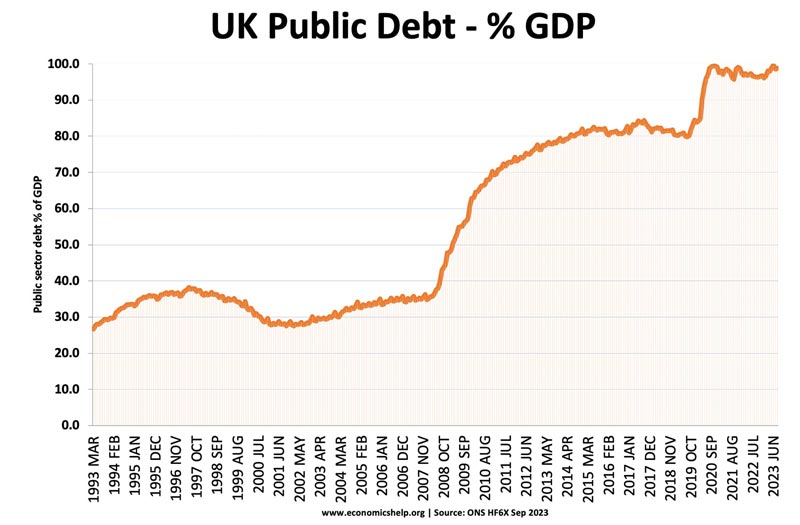

In 2010, UK debt to GDP was still low by post-war standards. But, despite rising demand for health care and an ageing population, spending cuts were pushed through. Austerity had two major costs.

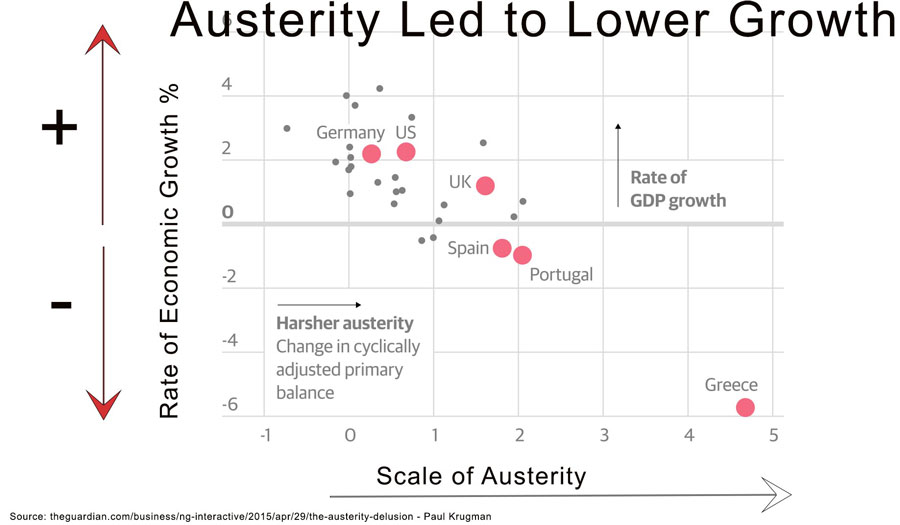

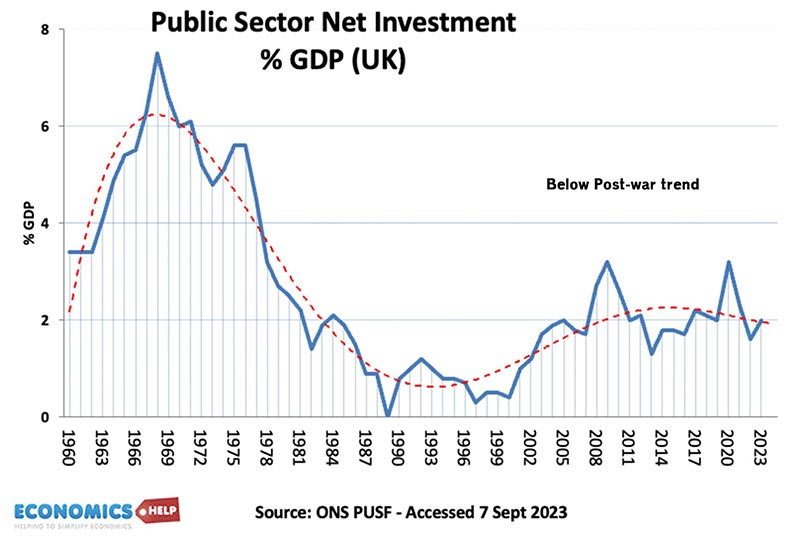

Firstly, in the short-term austerity reduced demand and slowed down the weak recovery. Despite spare capacity, quantitative easing, and a 30% devaluation in sterling, economic growth was unusually weak throughout the 2010s. Interest rates fell close to zero, but despite being very cheap to borrow, the government chose not to invest, it was a missed opportunity to improve the UK’s crumbling infrastructure or improve domestic energy capacity. There is a strong link between levels of austerity and slower rates of economic growth. It is bad economics to obsess about deficits when growth is so weak and interest rates so low.

One of the tragedies of the austerity era is that despite cuts to public spending, government debt rose anyway. Debt rose from 55% of GDP in 2010 to 100% of GDP in 2023. Now, some of that was necessary and even desirable for dealing with the Covid crisis, but the problem with austerity is that by contributing to lower economic growth, it leads to relatively lower tax revenue. In fact, to deal with lower-than-expected tax receipts, the government have been forced to increase tax rates as a share of GDP to record peacetime levels. Higher taxes have further squeezed living standards and held back business investment,

In 2023, due to inflation, nominal government tax revenues have increased and the government promised that taxes could be cut. But, importantly the Resolution Foundation states future government budgets are based on unsustainable cuts in real spending. High inflation increases nominal tax revenue but also needs to increase nominal spending. It’s also bad news for whoever wins the next election. Government budgets have been planned on impossibly tight budgets – a fiscal fiction. Unless growth recovers, we are facing more years of austerity.

The austerity of the early 2010s has also hit public spending and infrastructure. With growing NHS waiting lists, schools in need of repair, a growing backlog of court cases and many local authorities are on the brink of bankruptcy. These may not always affect growth immediately, but the cumulative effect is to hamper nationwide productivity and confidence in the economy, and this is the biggest concern of the past 13 years, the sharp slowdown in UK productivity growth. This is the main factor that determines future growth and the outlook is currently bleak.

Despite reducing public sector investment to 50% less than in the 60s and 70s, the government did back the ambitious and expensive HS2 scheme. Even amidst austerity, Cameron and Osborne were enthusiastic backers for a scheme which in theory would revitalise UK infrastructure. But, the partial cancellation of the scheme is symbolic of the difficulty in building things in the UK. It was felled by a combination of rising costs, mismanagement and government meddling with schemes to add more expensive tunnels to appease local MPs. Costs soared from £40bn to an estimated £130bn. In 2021, a government report still stated the scheme was still a net benefit, as long as it was built to Manchester and Leeds. But, the recent cancellations of the northern leg, means we are left with a £50 billion white elephant from a suburb of Birmingham to a suburb of London. It is the one leg of HS2 where the long-term benefits are never likely to exceed the costs. The failure of HS2 in the north only highlights the UK’s big inequality problem.

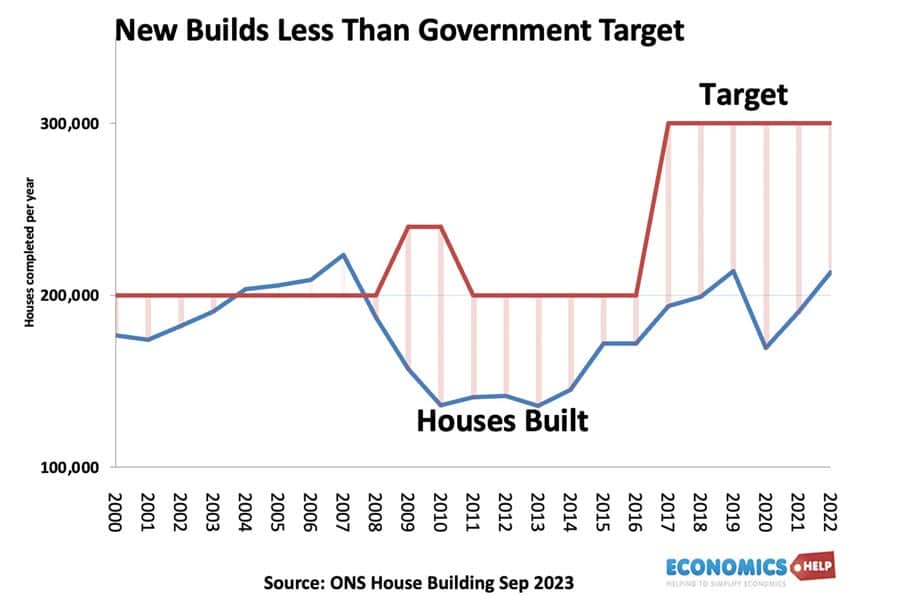

Housing crisis

Another failure of investment is in the housing market. Rising house prices and rents have been critical for damaging living standards, especially for the younger generation. Faced with rising house prices, one policy the government implemented was to help to buy, basically enabling first-time buyers to borrow more, but this did not tackle the underlying situation, it only aggravated the rise in prices by stimulating demand. Despite promises to build 300,000 homes a year, the government has failed to meet its own targets. It is worth adding, that a failure to meet housing targets has been a notable feature of the UK government, whichever party is in power.

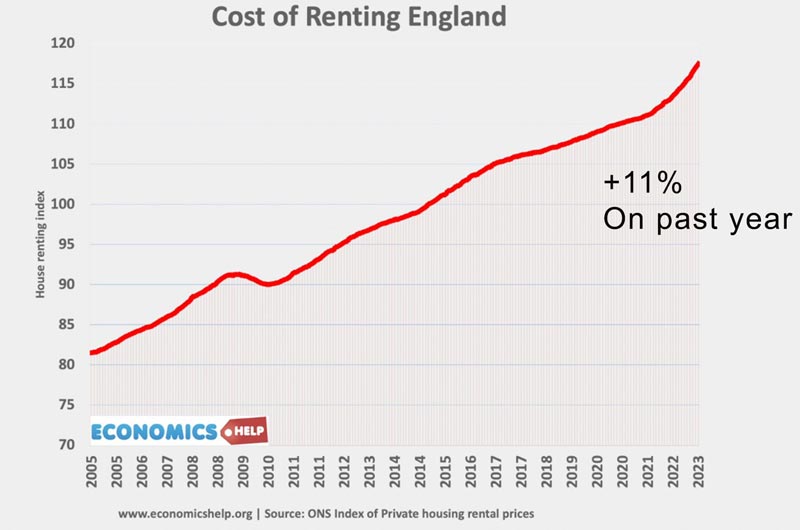

The housing crisis has become particularly acute in the private rented sector because the UK has a net loss of 1.5 million social housing since the early 1980s, causing demand for private renting to soar. Selling off council houses was popular to those who could buy at a discount, but the proceeds were never reinvested in building new social housing. It means that low-income households have been pushed into the private rented sector, which is struggling to keep up with rising demand. It hasn’t helped that some buy to let investors have sold up, fed up with higher interest rates and more government regulation. This is one area of the economy where the government could definitely have done more to reduce the excessive cost of living pressures.

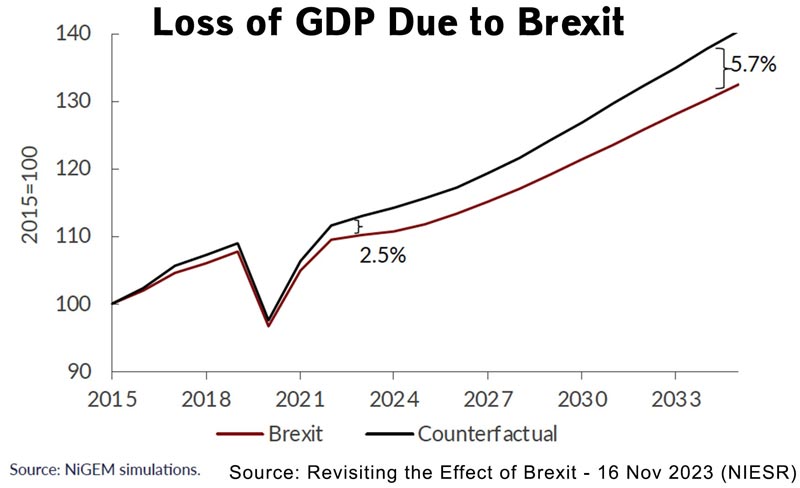

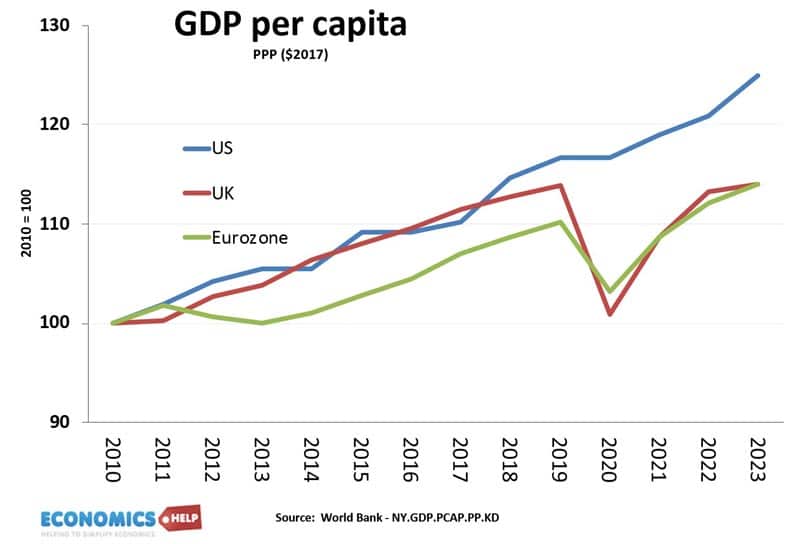

Another shock for the UK economy was the Brexit vote in 2016. It had four main economic effects, increased costs on trade with Europe, a devaluation of Sterling which raised import and food prices, a negative impact on investment and lower economic growth than otherwise. A NIESR model suggests that Brexit has caused GDP to be 2.5% less than otherwise. This will rise to 5% loss by 2035. This is similar to studies by the OBR and UK in a changing Europe. It is important to stress Brexit does not mean the UK will be in perpetual recession, it is more like a slowly deflating balloon – it’s something you don’t particularly notice when its happening. Since 2016, UK growth has been similar to the Eurozone, but much less than Europe.

Also, some of the predicted negative effects of Brexit have not materialised because EU migrants have been replaced by non-EU migrants. But, although it is not calamitous, by 2035, UK GDP per capita will be an average of £2,500 less because of Brexit. A Brexit that involved staying in a single market or customs union would have had very minimal economic costs. Here deliberate government policy has had a big effect on the economy.

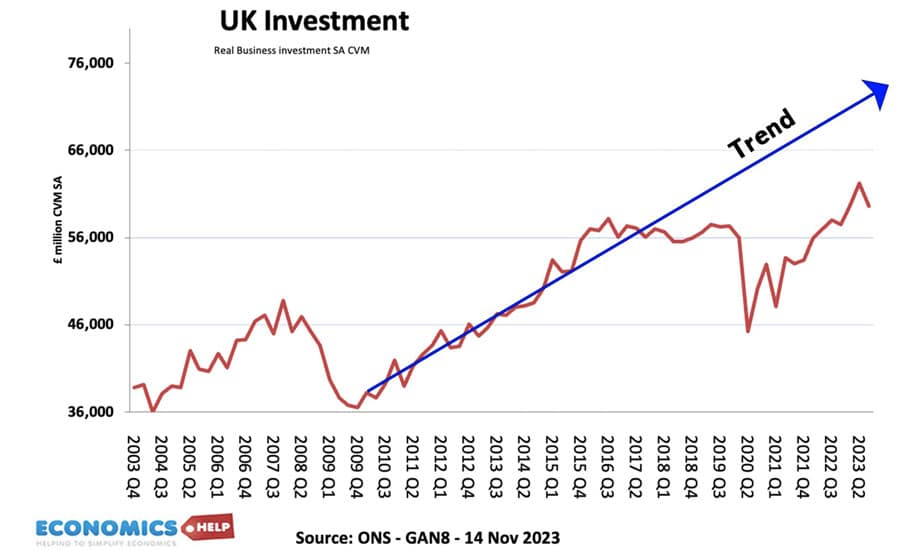

Brexit also had a clear impact on investment, with uncertainty reducing investment growth quite markedly. The UK has one of worst levels of investment in the OECD, not helped by recent rise in interest rates which only further reduce investment. Tackling UK investment will be big challenge.

Overall

With the exception of low unemployment, the UK’s economic performance has been very poor in the past 13 years. To some extent, the government have faced difficult circumstances a slowdown in global productivity growth, the twin crisis of Covid and the Ukraine War. But, although they have been dealt a difficult hand, there are also a few self-inflicted wounds. The long-drama of Brexit definitely undermined investment and frustrated businesses who face higher costs. The austerity of the 2010s was driven by ideology rather than sound economics. It is a legacy of slower growth and under-investment. And despite one party being in power, there has been a surprising amount of flip-flopping of policy from the austerity of the Cameron era to the radical stimulus of Truss and Kwarteng. Tax rates have fluctuated and there is a lack of coherence and stability in many government departments, such as housing.

Sources

https://www.niesr.ac.uk/publications/revisiting-effect-brexit

Taxes are at a 70-year high, yet some 7.7mn people are on hospital waiting lists, schools are crumbling and ministers want to rent space in foreign jails because UK prisons are full.

The Resolution Foundation think-tank has warned that spending plans pencilled in by Hunt for the next parliament are “a fiscal fiction”.

https://www.ft.com/content/8c6461c6-e976-4563-b277-bf61ae0a2c07#selection-3109.168-3109.304

UK business investment has grown only 4.6 per cent since the start of 2016 when it began stagnating — in part reflecting high uncertainty following the Brexit referendum.

By contrast, there has been a 32 per cent expansion in US business investment since the start of 2016 and 15 per cent growth in the eurozone, according to data collected by Oxford Economics.

https://www.niesr.ac.uk/publications/revisiting-effect-brexit

Dear Mr Pettinger

An admirable summary. There are always things one would have done differently but I have no real complaints.

But I do have one or two minor quibbles, which I hope you will accept in a spirit of wishing to improve something already very good indeed.

1st sentence: UK economy [grow => grew] at 2.5% a year, but since [the] great financial crisis …

2nd sentence: The OECD report that .. => reports

? You do not answer the question [economy has deteriorated..] And importantly can we turn it around ?

– Interested to see your suggestions (which I hope are nothing like the Resolution Foundations’ ones).

In “Causes of Growth Slowdown” : you have a chart “Austerity Led to Lower Growth” which looks very like one I remember from the IMF some time ago – ah, I see it is, as quoted by Krugman. Now he sensibly gives the dates it applies to: 2009-13. Maybe you could include that small detail, please ? After all the actual “austerity” period was limited, it is just that since Osborne, no other Tory has been interested in social investment, either, so nothing has improved (a point you make slightly differently elsewhere).

Later in that section you note, correctly, that despite spending cuts, “government debt rose anyway… some of that was necessary and even desirable for dealing with Covid …” Would you care to enlarge on what was necessary, apart from lower tax revenue? – as it seems to me that under Brown at the beginning some of the debt was related to the bank bailouts but not much under Osborne, unless I am misremembering.

Debt: Oh and of course GDP and tax revenue changes &c.