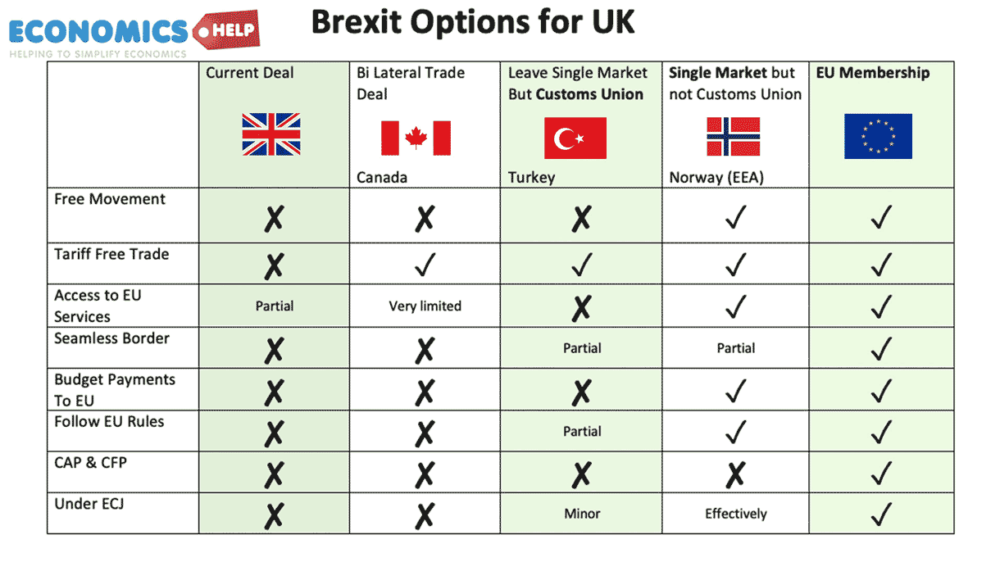

In 2016, the UK voted to leave the EU. Before, 2016, Eurosceptics would talk in admiring terms of Norway and Switzerland. Countries outside the EU, but with most of the economic benefits.

The problem is that after the simplicity of a campaign to leave the EU, the question of what came next was surprisingly tricky. The UK had got used to special deals. EU membership but special exemptions on the Euro, Shengen, even a financial rebate. But, it soon became apparent that when you were outside the EU, it was much harder to have your cake and eat it. The UK had hoped it would be able to appeal directly to national governments, e.g. special access for German car exporters to the lucrative UK market.

But, it didn’t work like that – the EU retained a disciplined approach to the four freedoms of movement – trade, capital, services and people. This was not up for negotiation. The UK was faced with a series of undesirable trade-offs, that no-one really liked.

After months of hard negotiation, in 2019, the Prime Minister brought back a Brexit deal, that parliament promptly rejected. The biggest government defeat on record. Parliament tried different variations of this deal – a custom union, common market 2.0, a 2nd referendum – but nothing could get a majority. It was easy to say what was unacceptable, but difficult to agree on a viable option. The deadlock was a curious combination of remainer MPs wanting a second referendum, and those who felt it was not Brexit enough. The referendum was so simple, but negotiating an acceptable deal much more difficult.

Of course, there were others factor at play. Vote Leave had hoped Brexit would be start of a domino of other countries wanting to leave the EU. They believed or hoped that once Britain had left, other countries would line up to join them. But with political parties across Europe tempted by Euroscepticism, there was little incentive for the European Union to reward leaving the European Union. There would definitely be no special exemptions and have your cake and eat it.

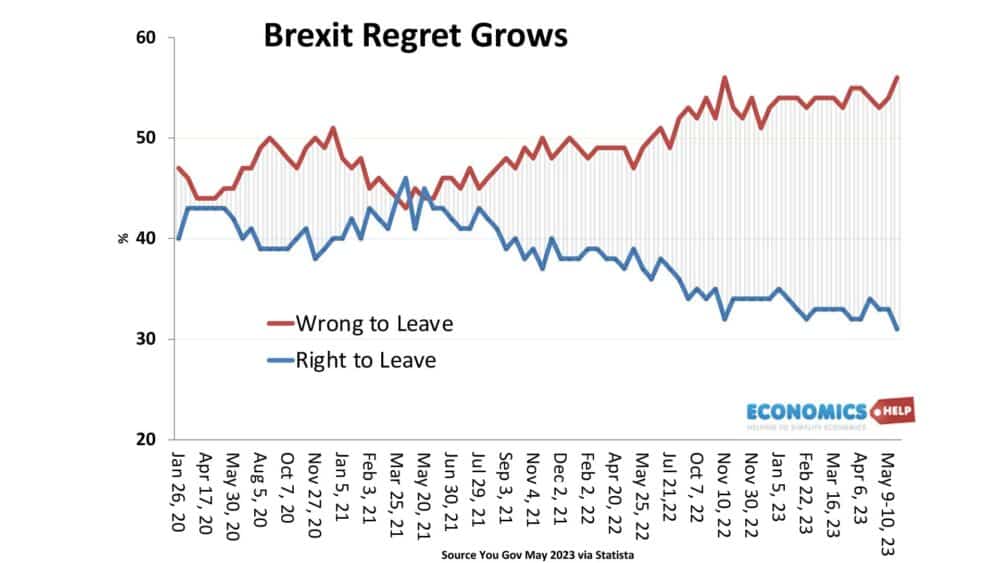

The difficulties of Brexit was remarkably effective in shoring up support for the EU across the continent. In the UK Brexit has become steadily more unpopular. Support for rejoining steadily grows each year, one of the main reasons is demographics. In 2023, Over 65s supported Brexit 56% to 36%. Amongst 18-24 year olds it is 7% in favour 70% against. As older votes pass on, Brexit support dwindles, and new voters see little reason to embrace Brexit. In the EU, support for EU membership has increased.

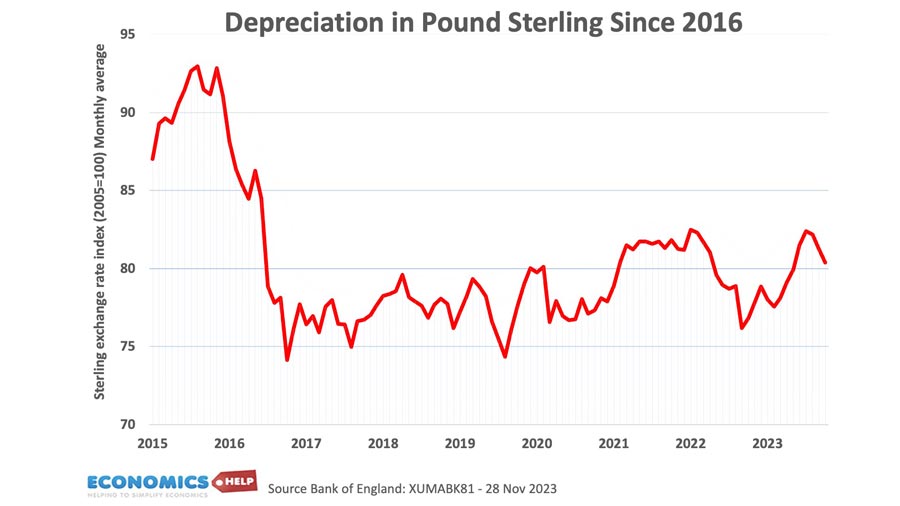

In the immediate aftermath of Brexit, the Pound fell 13% and has remained weaker ever since. This reflects the market’s lower expectations around the UK economy outside the Single Market. This depreciation pushed up import prices increasing the price of food and energy, a problem exacerbated by all the inflation of recent years. Whilst this is a clear cost, the worst forecasts of immediate economic doom, were also wide of the mark. The vote itself, actually changed little. Even leaving the Single Market in 2021 didn’t precipitate a recession. Since 2016, using purchasing power parity, the economic growth of the UK has not been much different to the Eurozone. In fact the whole European continent has slipped behind a booming US economy.

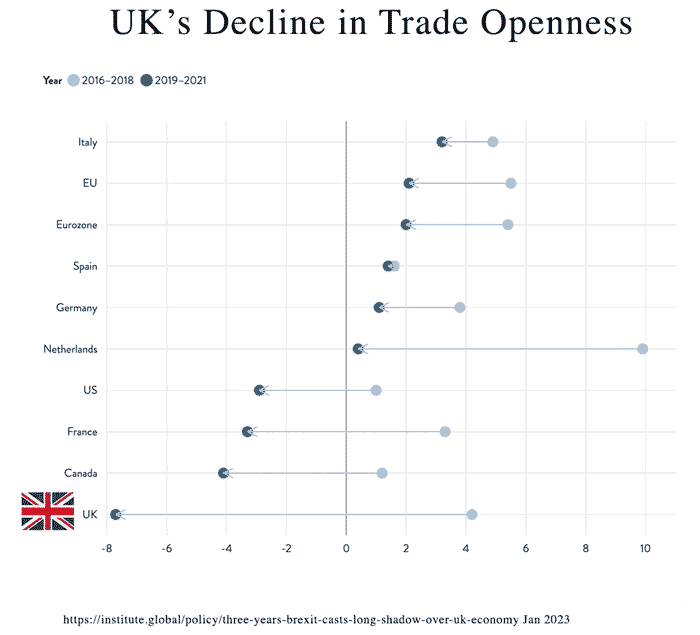

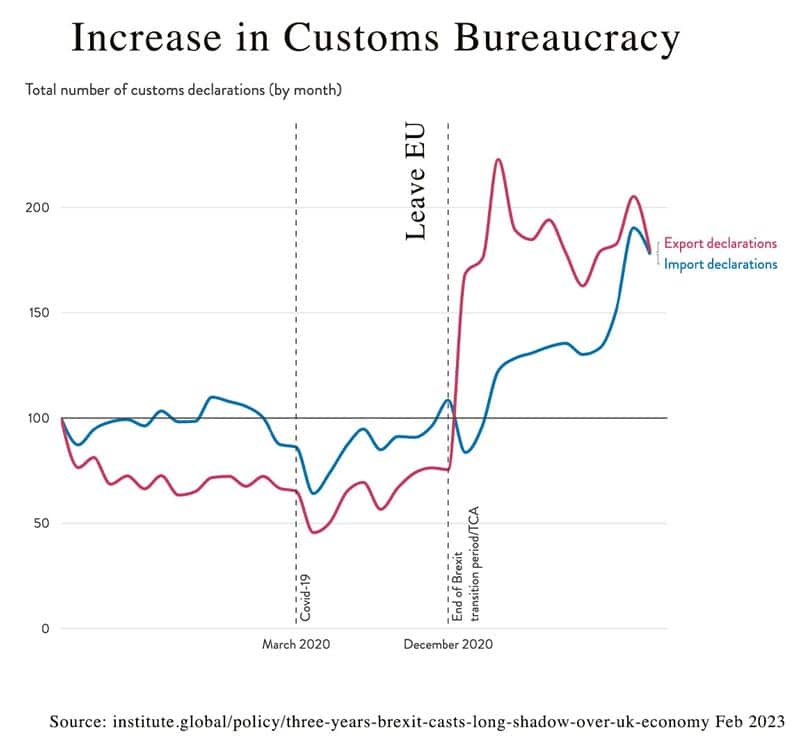

However, there have been very real economic costs of Brexit, which will be increasingly felt over the next few years. There has been a decline in trade openness, increase in bureaucracy and other trade frictions.

Something that is particularly hurt small and medium sized firms the British Chamber of Commerce found 92% report significant challenges with new the trading deal. 80% face higher import costs, causing some firms to go out of business.

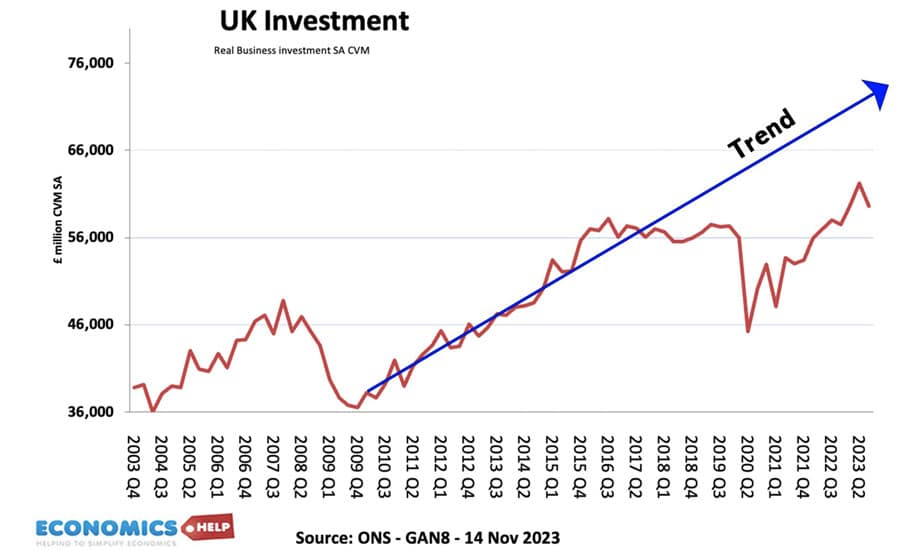

Business investment slumped post 2016, as firms were deterred by all the uncertainty and new costs of trade. 69% of farmers say Brexit is bad for business. Numerous studies have shown that Brexit will cause a net loss of around 4-5% GDP over a period of 15 years. This is reducing average growth rates by 0.3% per year. It is the kind of figure that is not particularly noticeable at the time, but after 15 years, the economy will be £2,500 per person smaller. It is a loss of income that the UK voters are not particularly keen to absorb. And, in 2024, UK firms will face even new costs of doing business with Europe as a result of Brexit.

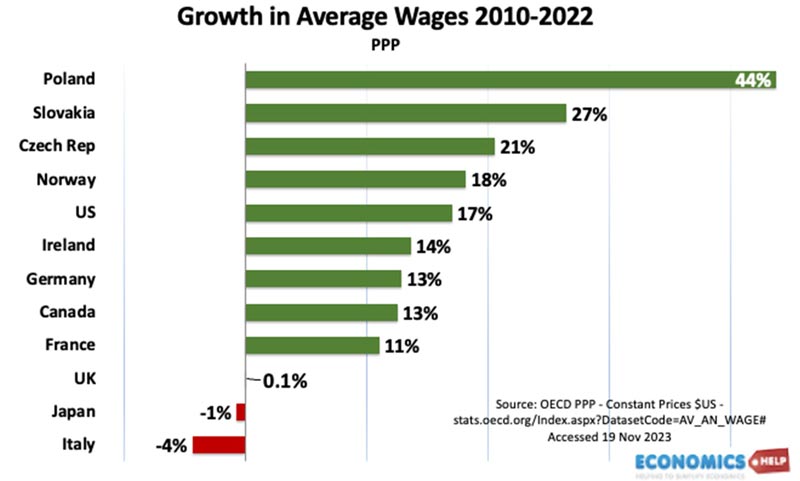

If Brexit had occurred during a long economic boom, its negative effects might have been shrugged off, but unfortunately it co-incided with a period of stagnant real wages, record inflation and a general economic malaise. The economy was vulnerable to the shocks and uncertainties Brexit created. Since 2016, the UK has seen zero growth in average wages, one of the worst in the world.

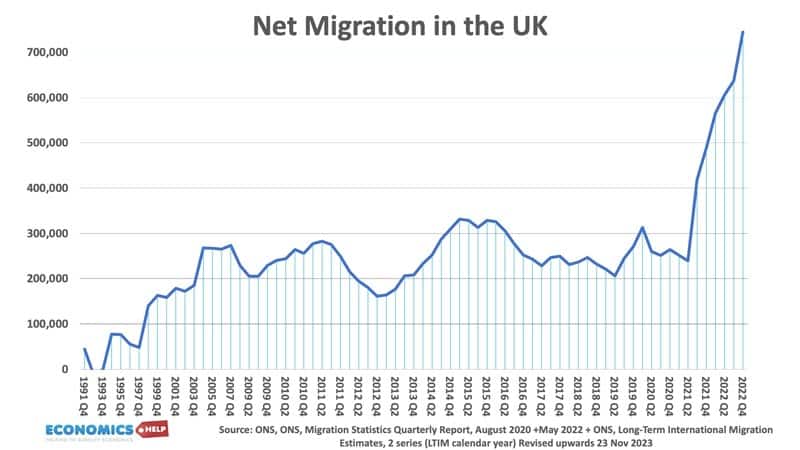

One of the motivations for Brexit was to end free movement of labour. In the preceding years, the UK had seen growing migration from eastern Europe due to the difference in wages and a booming job market in the UK. But, many felt high levels of migration were pushing up rents and pushing down wages. Since Brexit, net migration from Europe has fallen away to zero, but ironically, net migration levels have increased to levels much higher than whilst in the EU. Migration from non-EU countries have soared.

But, there’s another interesting feature. In the 2000s, Polish wages were three times less than the UK, no wonder there was so much net migration. But, Polish wages are fast catching up with the UK. On current trends, Polish wages could exceed British wages by the late 2030s. Even if they don’t quite catch up, the large wage disparities which fed economic migration will dissipate. Free movement within Europe will be less problematic in the future.

The problem is that although public opinion slowly moves against Brexit and in favour of rejoining, it also becomes much harder. Even if the UK indicated an interest in rejoining, the EU would be wary. Also, even if a new generation of politicians wanted to rejoin, it would be less attractive than the past deal. The UK would struggle to regain its raft of favourable concessions and in theory, would have to commit to joining the Euro. Something that would make it increasingly unlikely.

Brexit has thankfully become less divisive as the issue slips behind other problems like the cost of living crisis. But it does highlight the difficulty of solving complex constitutional questions by a simple majority referendum, especially when the deal you are voting for is unclear at the time. Nearly seven years since the vote, there remains little enthusiasm for Brexit and a sense that the same problems still need solving. It remains a cautionary tale for other European countries. Still the worst is over, and in recent years, there have been signs of better relations between the UK and Europe, which is very welcome.

https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/article/comment/winners-losers-and-ones-watch-brexit-indicative-votes

Thanks for this sobering analysis. On the “current deal” (the box): surely the TCA does provide for tariff free and quota free access for goods? What we have now are, of course, non tariff barriers. Many Brexiters failed to see that tariffs per se were not what they once were (in view of the WTO) but that non tariff barriers are a major problem outside the Single Market. I wonder if the emphasis should be first and foremost to get the U.K. back into the Single Market via a reformed (more democratic) EEA. Perhaps along with Ukraine. ??

Trade is at a record 94 billion. The conservative party is remain as signified by Cameron. Since 2018 we have expanded far quicker than Germany and they have had all these advantages you talk off. Because of the democracy afforded by Brexit our government is accountable to us, again. Such a priceless thing as democracy should never be sold or traded away as per Michael Foot and Tony Benn

The first part of your comment makes no sense. Am not sure if you have left out some key words (?). As to the “democracy” issue, I feel I now have less say on laws that impact me. The UK is, and will always remain, aligned with the vast majority of the rules of the Single Market. It is one of the three major economic blocs in the World and it is right next door to us. (And look up “the Brussels effect”). But we no longer have a say over the laws which impact us. I did have votes: directly for the European Parliament, and indirectly for our Government which had a vote in the Council of Ministers (it was very rare for QMV to be formally invoked: consensus is usually the name of the game). No longer. Ironically, one of the first acts of our “brexiter” government was to take away scrutiny of trade deals from Parliament. There is less accountability and “democracy” now than when the UK was in the EU. (PS. I still maintain that there is an error in the table at the top of this article. The UK/ EU agreement DOES provide for tariff free trade in goods, albeit subject to content provisions. As mentioned above, this does not of course permit free circulation within the single market and has therefore led to a significant reduction in our terms of trade compared to what would have been the case: whatever john pugh may think… So the cross should surely be a tick??).