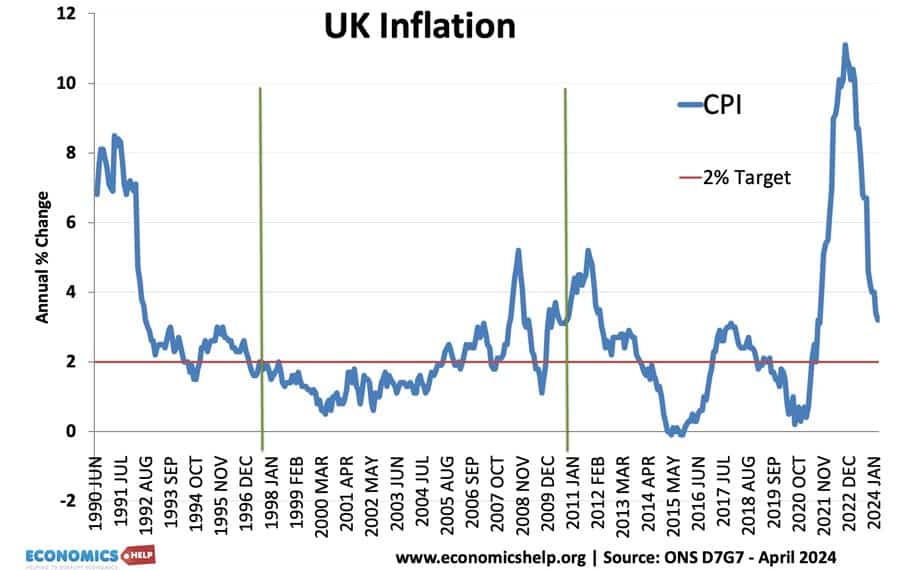

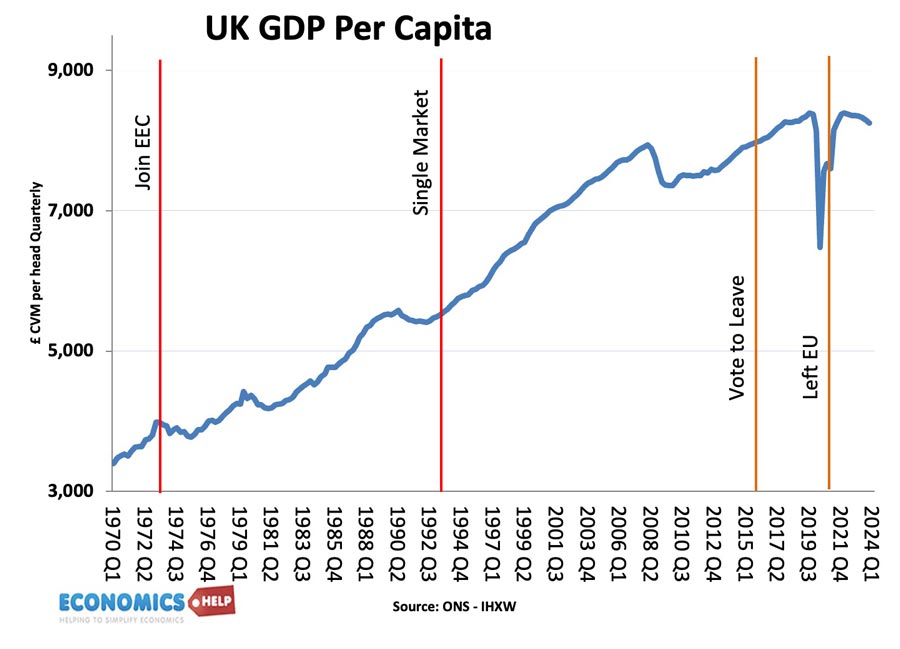

By 2007, New Labour had presided over the longest period of economic growth in the post-war period. It was the goldilocks economy with low inflation, low unemployment and an impressive rise in spending on the NHS and education. But, the devastating global credit crunch caused a deep recession and higher unemployment.

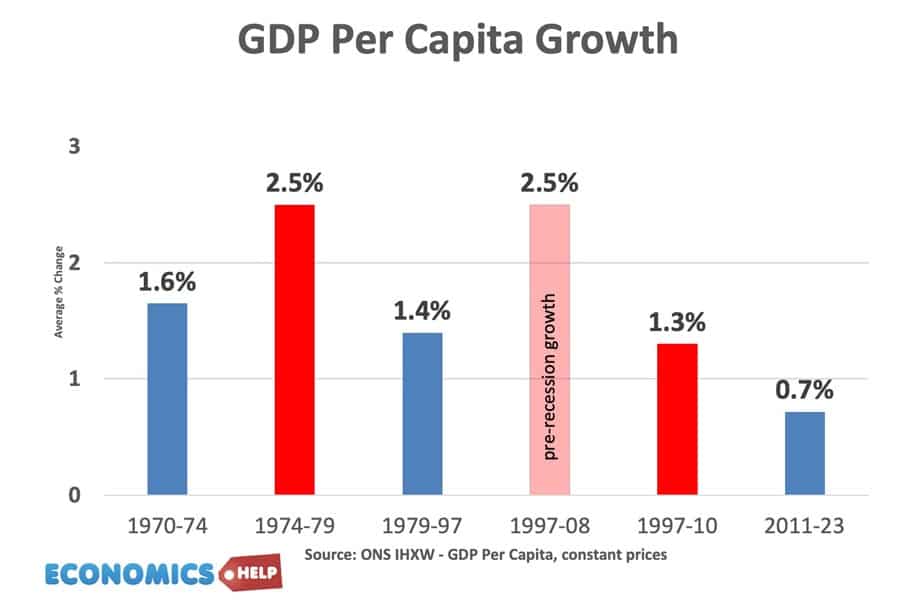

Average GDP per capita growth fell from an impressive 2.5% to a below-average 1.3%. But, how much blame does Brown and Blair deserve for the 2009 recession and how much credit for the overall economic performance? But, first what actually happened in the period of New Labour.

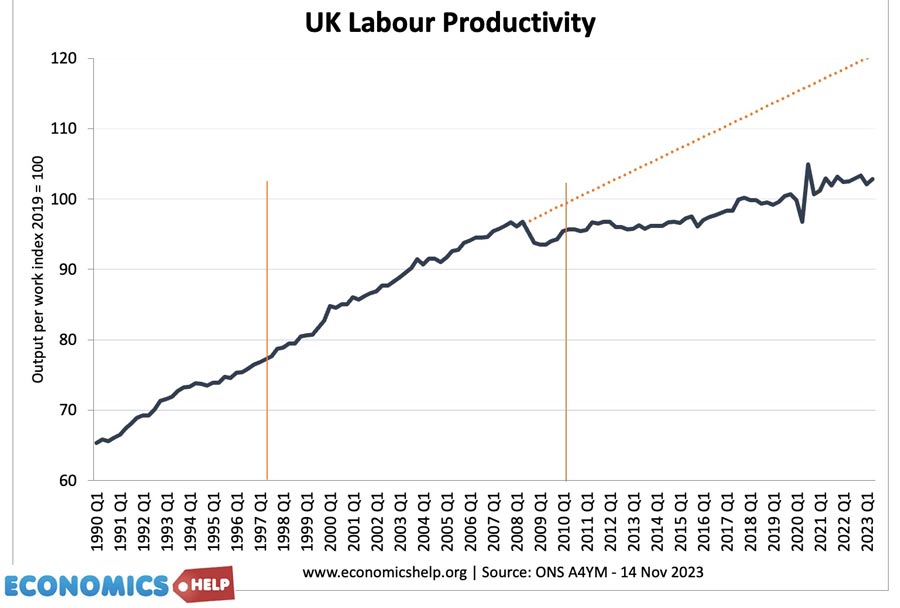

John Van Reenen from the LSE, claims that up to the start of the 2008 recession, the New Labour era saw impressive productivity growth of 2.8 % a year – one of the highest in post-war period and a stark contrast to what has come recently. Van Reenan claims the economy benefited from past supply side policies, but also New Labour policies on competition, research and development and education. It certainly helped that in 1997 Labour inherited a reasonably good economy with national debt close to the lowest level for 80 years. After the ERM debacle of 1992, the UK economy recovered and by 1997 had a decent momentum, with growth averaging 2.5%, but inflation well under control.

Stability

One of the first rules of good governance is not to do stupid things. For example, allowing inflationary booms like the 1970s or late 1980s. In fact, a key economic policy of New Labour was giving the Bank of England monetary independence. No longer could government ministers use interest rates to promote a pre-election boom. Until 2008 at least, this was considered a stabilising influence for the UK economy. Also, if you compare New Labour government to the post-2010 Conservative government, there was also no self-inflicted wounds like austerity, Brexit or Truss budget debacle. But, to avoid disastrous policies is a fairly low bar.

In reality, a significant portion of the UK economic growth was not due to government policy but the momentum of the private sector. A strong area of economic growth was from the finance sector. The growth in finance can be traced back to the big bang banking liberalisation of the 1980s. By 2004, finance and business services made up 33% of the UK economy with investment in this sector almost four times higher than in manufacturing and other industries. The UK benefited from the credit bubble of the early 2000s and the new wave of complex financial instruments. However this was to have devastating consequences. The net effect was that the boom in financial services slightly exaggerated UK economic performance up to 2008. One reason for the abrupt decline in UK tax revenue and economic fortunes post-2010 was the hit to finance from the global credit crunch.

Inequality

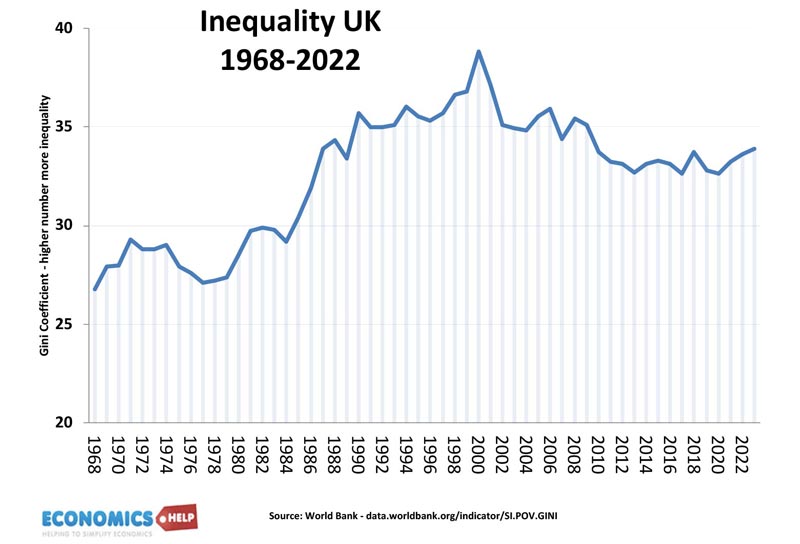

Another impact of the growth of finance was to see a growth in incomes of the highest paid. This explains the slight increase in income inequality towards the end of the New Labour government. Overall inequality remained largely flat However, on the metric of inequality, New Labour did introduce some modest policies to redistribute income. In 1997, the National minimum wage was introduced at a level of £3.30 an hour. It was strongly opposed by many who argued it was cause unemployment. But, this didn’t materialise and has gone on to become one of the most successful economic policies for boosting the wages of low-paid workers.

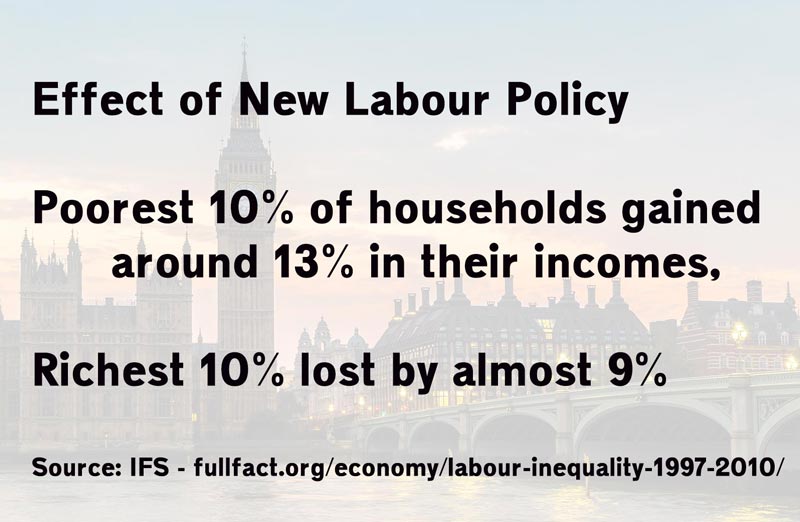

The IFS notes that government policies on tax credits and benefits played a role in reducing inequality, and reducing poverty epecially for children and pensioners. But, it was fragile in that it was based on government benefits rather than underlying income. The improvements were vulnerable to later austerity measures. Overall New Labour implemented modest redistribution. The IFS calculate the net effect of government policy was the poorest 10% of households gained around 13% in their incomes, whilst the richest 10% lost by almost 9%.”

Government spending

In 1976, the Labour government was forced to borrow from the IMF. It was due as much to a balance of payments crisis as high government borrowing. But, it cemented a reputation for Labour fiscal incontinence which Tony Blair was keen to change. The first four years of New Labour saw very conservative spending plans. But, after the 2001 election, New Labour resorted to be a more traditional tax and spend party. Both tax and government spending rose as a share of GDP Though spending rose quicker.

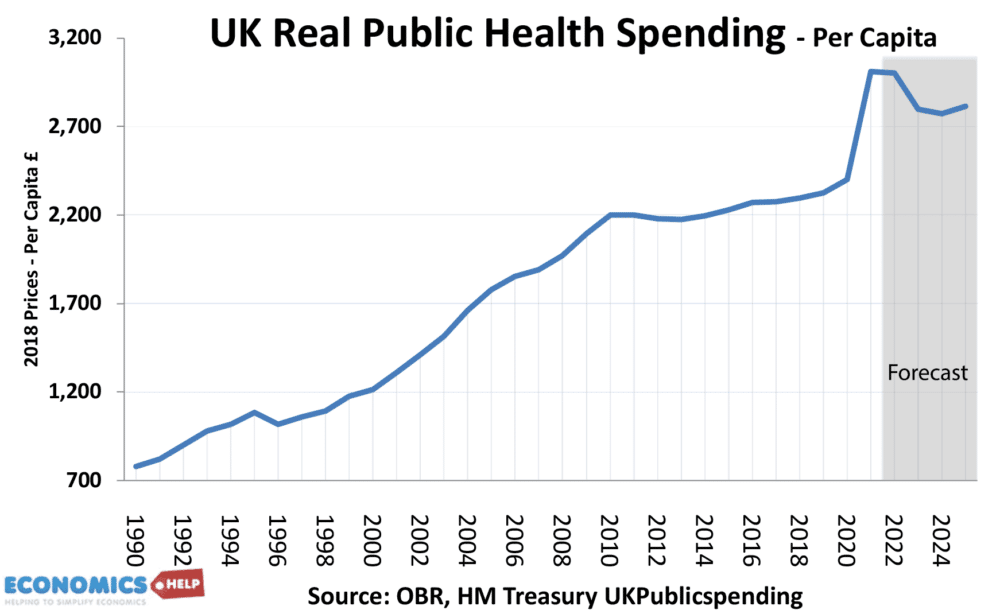

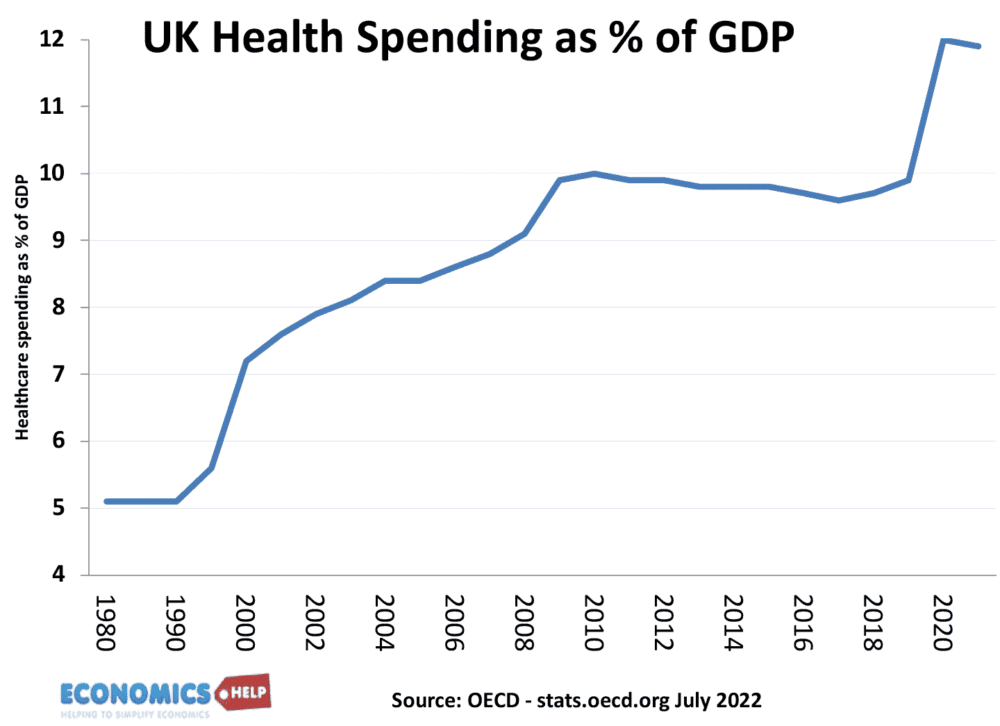

The biggest beneficiaries was the NHS. In 1997, health spending as a share of GDP was well below the OECD average. Under Labour it increased from 5.7% to 10% in 2010.

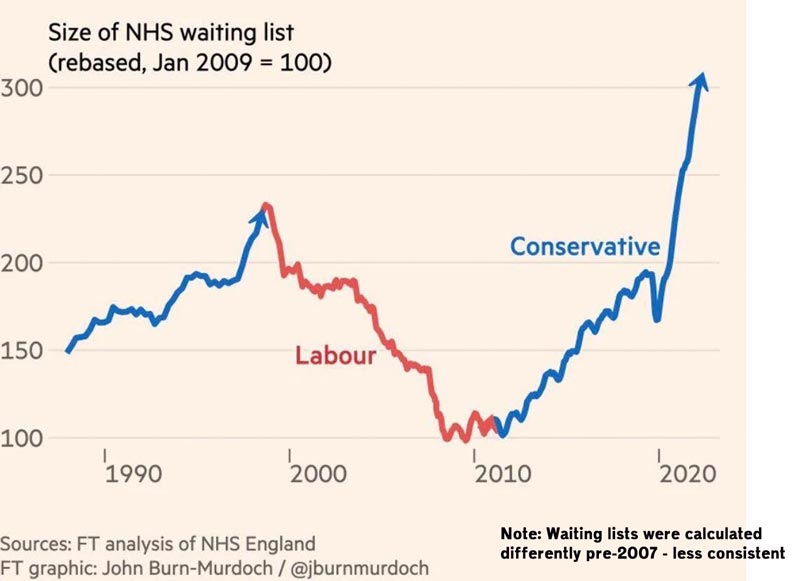

Even in real terms, per capita spending almost doubled. The average wait for hospital inpatient care fell from 13 weeks to four weeks. The impact on waiting lists contrasts sharply with the post-2010 situation. Although worth mentioning waiting lists are measured differently. Also, the increase in money for the NHS post 2001 was so rapid, it wasn’t always used most efficiently. With the extra money also came increased policy meddling and a rise in bureaucracy.

Capital spending rose from £1.1bn to £5.5bn over the decade to 2007-8. That money built 100 hospitals, pushing the average age of NHS buildings down dramatically

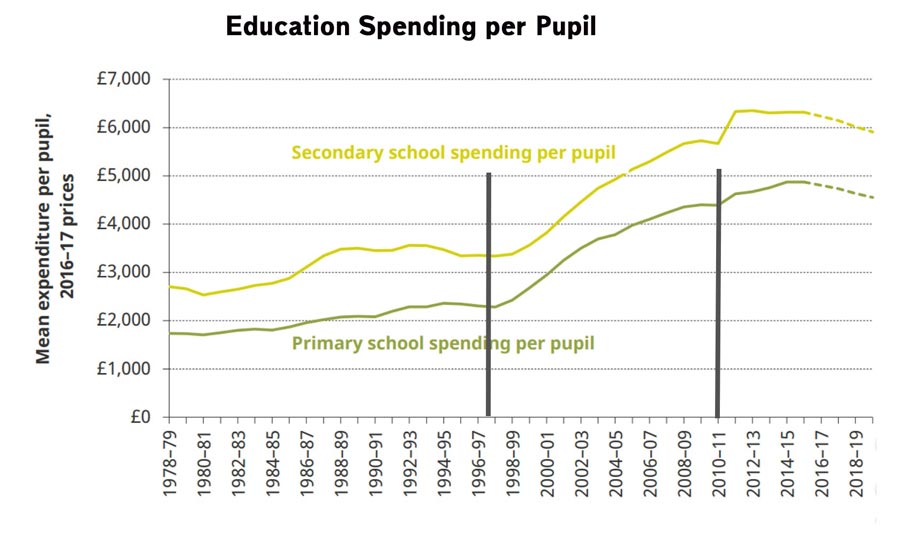

Education

It wasn’t just health, education saw a rise in spending from 1.6% to 5.7% of GDP, with real spending nearly doubling from £56 to £103 billion. This included sure start for under fives and an expansion of university education with a government target of 50% school leavers going to university. 10 years after 1997, graduate numbers rose from 1.8 million to 2.4 million. Whether this expansion in student numbers is sustainable is a good question with many universities struggling financially and tuition fees rising substantially.

PFI

It is also worth bearing in mind, that this government spending was also part financed by private finance initiatives. By 2008, the total value of PFI contracts was £68bn. The idea was that the government would use private investment to help fund public investment. It committed the British taxpayer to future spending of £215bn. After the credit crunch private investment dried up, so the government had to fund the private investments itself, leaving a ridiculous situation of the government lending itself money to fund PFI. In 2018 a report by the National Audit Office found that the UK had incurred many billions of pounds in extra costs for no clear benefit through PFIs

Net Migration

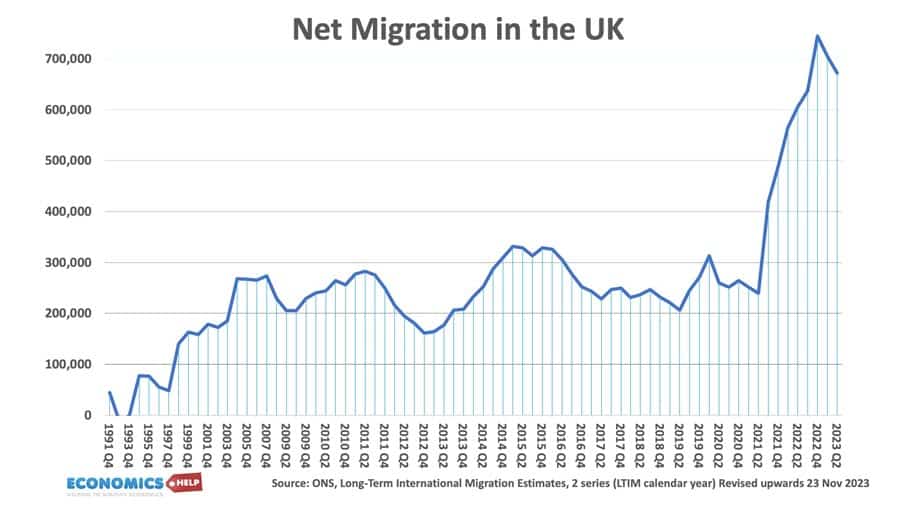

Under New Labour net migration was averaging close to 200,000 a year, only marginally higher than previous 10 years. Yet, the decision to immediately allow migration from Eastern Europe after the ascension of countries like Poland would have a large impact, not many foresaw. Interestingly in 2004, with rising real wages and low unemployment, the decision was uncontroversial and had bipartisan support.

National Debt

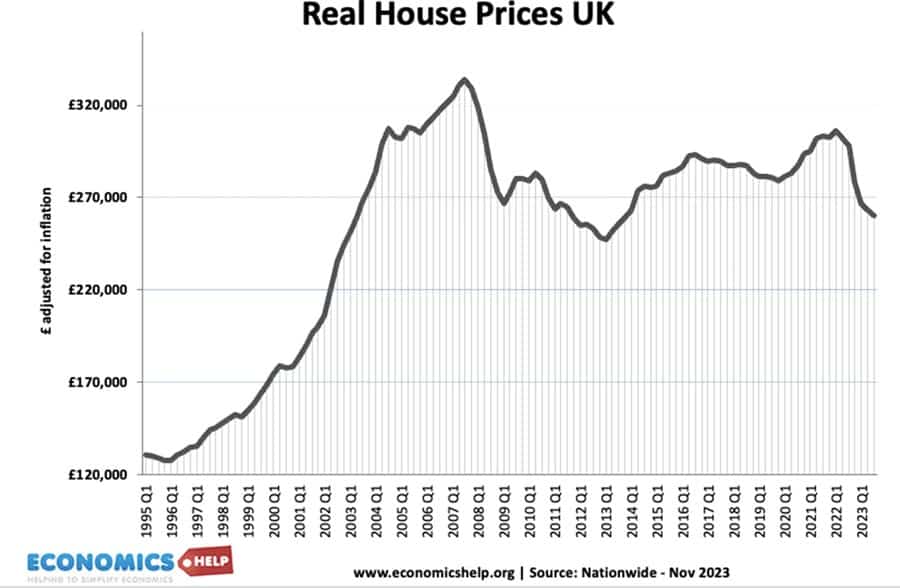

Despite a significant rise in government spending as a share of GDP, national debt continued to hover close to historical lows. It was only the credit crunch of 2008, which saw record peace time budget deficits. One mistake was relying on tax revenues from the finance sector. Given the disastrous impact of the credit crunch how much was it due to the policies of Blair and Brown? Firstly the credit crunch was a global event, with the primary problems starting in America. Reckless mortgage lending, a boom and bust in house prices, and aggressive bank lending caused the whole financial system to come under severe pressure. There is nothing a UK government could have done about the financial excesses in the US. However, the UK had its own reckless lending. Building societies which became banks like Northern Rock and Bradford & Bingley had aggressively sought to lend more mortgages by funding mortgages from short-term money markets. When the credit crunch hit, the banks were deeply exposed and required a government bailout. In 2007, the UK mortgage market was badly regulated. Self-certification mortgages, 100% interest-only mortgages all helped contributed to a boom in house prices, which then saw a 20% fall after 2009. A foresighted government would have reversed the financial liberalisation of the 1980s and early 90s and introduced better regulation. But, it was a topic that received little interest before the credit crisis.

Credit Crunch

The credit crunch damaged the economic record of New Labour, but does Gordon Brown deserve more credit for pursuing the best response to the real crisis? There was bold action. Bank recapitalisation and nationalisation to prevent further loss of confidence. It may not have saved the world, but it did help save a global economy, tottering on the edge. Given the depth of the recession and fall in spending, the government pursued a loosening of fiscal policy, VAT was temporarily cut and this did help the economy to recover. By May 2010, the UK was growing. Politically, the high budget deficits was costly. But, in a recession, that is the textbook response. Austerity in a recession only slows down the economy and prevents a recovery in tax revenue. Arguably the austerity of the post 2010 Conservative government slowed down the UK’s recovery to a near stagnation. A continuation of Brown’s economic policies may have enabled stronger recovery and a better performance in the 2010s.

Housing Market

Another long-term issue in the UK economy has been the housing market. Under New Labour, there was a boom in house prices with house price to incomes reaching record levels pre-2008 crisis. During the period of New Labour, housing supply continued its low levels. Only briefly exceeding the government’s modest target of 200,000 homes a year before the credit crunch set back building again. Arguably this was another missed opportunity of the period, a failure to get to grips with the UK’s growing housing crisis which would magnify over the next decade.

Overall

The main feature of New Labour was a significant increase in public spending on the NHS and education. This was partly funded by economic growth and partly through a rise in borrowing. It was a necessary injection of cash, even if it was not always used most judiciously.