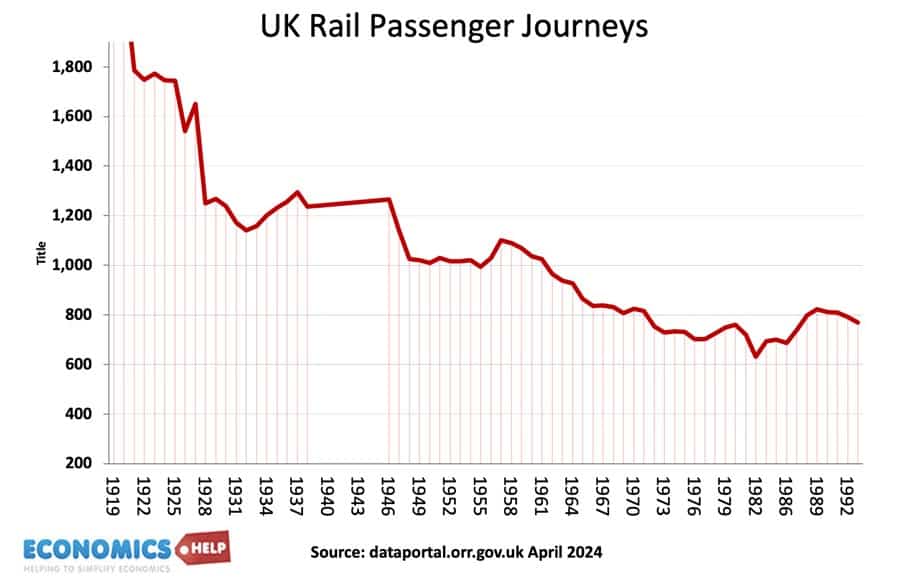

In the Victorian age, the UK led the world in building railways, it was an invention that changed the world. But, by the 1980s, the state owned British Railways was the butt of jokes, stale sandwiches, declining passengers and closed lines. The railways just couldn’t compete with the convenience and lower cost of motorway Britain.

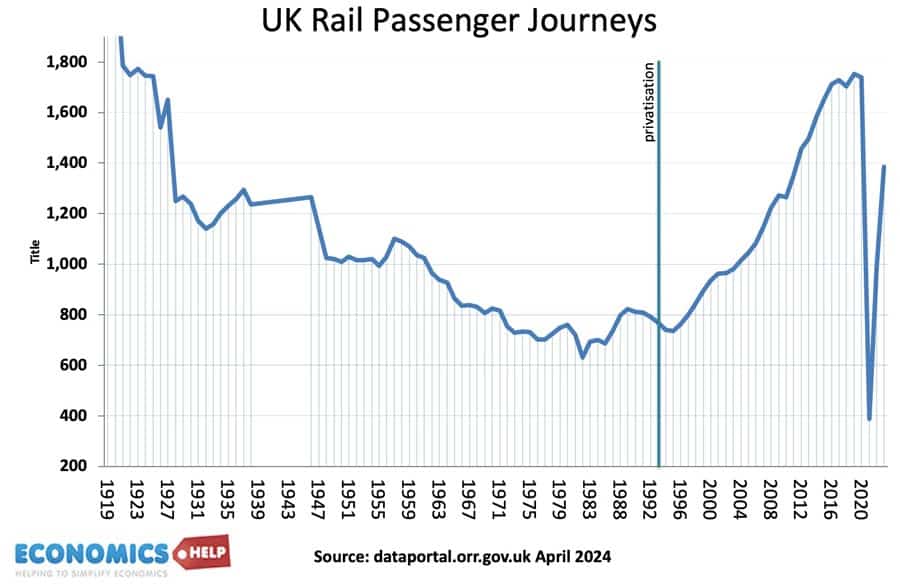

Yet, even the great free-marketer Mrs Thatcher didn’t dare privatise British Rail, she believed, it was a step too far. But, in 1993 under John Major, British Rail was privatised, and broken up into many separate units. It was hoped, privatisation would cut costs, improve competition and improve services. And in the years following privatisation, passenger figures did rise significantly. It was part of a European wide boom in train travel, a response to congested roads, higher economic growth and private companies attracting new customers.

However, despite rising passenger numbers, cracks in the model of privatisation soon started to appear. The fragmentation of the network meant there was no guiding hand or overall vision. The Hatfield crash of 2000 due to poorly maintained track set off a panic, with Railtrack imposing speed restrictions and undergoing hasty maintenance. The disaster led to the demise of Railtrack and its effective nationalisation. Government subsidies to the rail industry soared as problems of creaking infrastructure became apparent.

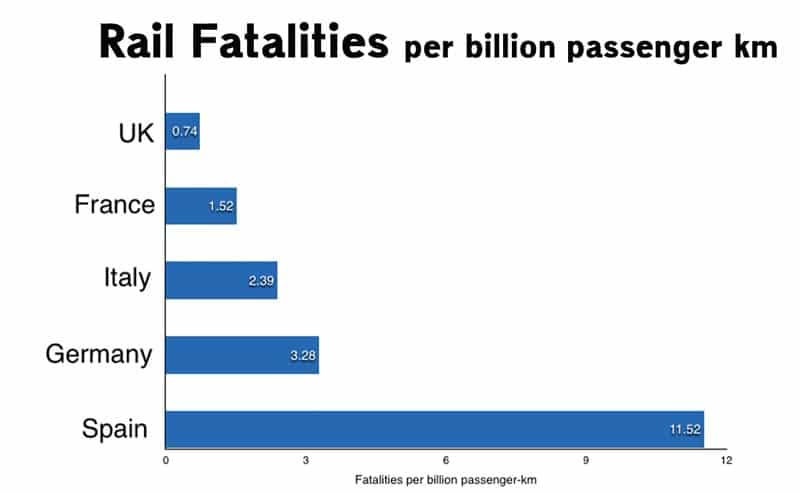

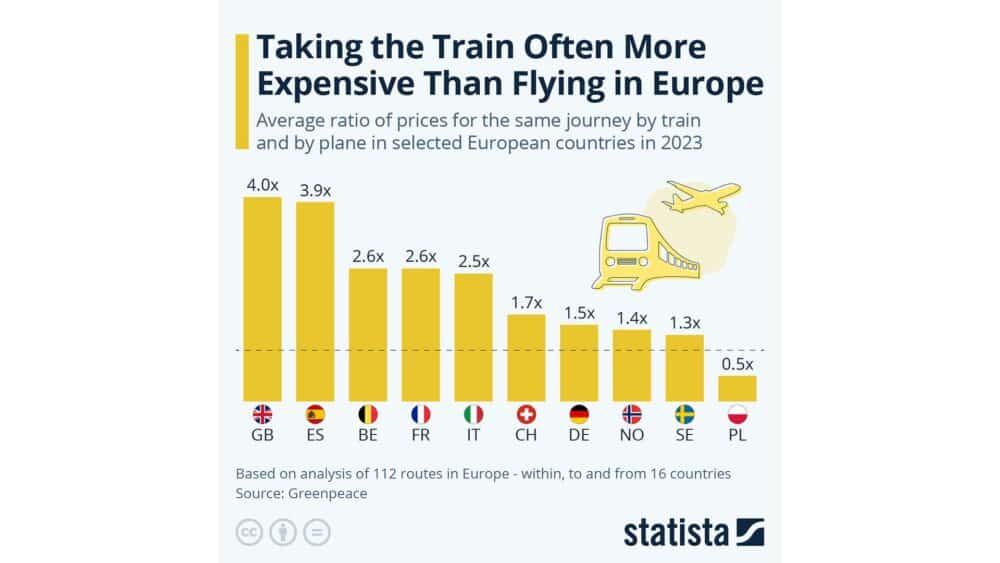

Though it is worth mentioning the UK rail safety record is one of the best in Europe, rail travel is significantly safer than British road. Passenger numbers may have risen since 1993, but privatisation failed to put a lid on costs, and passengers have witnessed two decades of above-inflation price rises. It means the UK has one of the most expensive rail networks in Europe, though we will look at this in more detail later, as this question is not straightforward.

The basic model of privatisation was franchising, companies would bid for the right to run services. However, the fragmentation of the network only created an illusion of competition. The FT report an internal government document of the time, admitted local monopolies were a political trick to gain local approval. It was pretend capitalism. The esteemed railways writer Christian Woolmar points out the basic problem of privatising rail is it that it is a natural monopoly, requires considerable public investment, and provides an essential public service.

It is true, that railways are used primarily by higher income commuters, hardly a surprise given cost of tickets. But, when rail fails, everyone suffers more road congestion and lost productivity. Even Tory Minister, Sir Malcolm Rifkind admitted the chosen model of privatisation was “irrational, bad economics and bad business sense”. Many European countries looked at the UK’s bold privatisation experiment, but it is telling that no-one has wanted to copy the UK model.

Failed Franchises

One of the few genuinely profitable rail routes in the UK was the East Coast Main Line between London and Edinburgh. Since privatisation in 1997, three private franchises have failed causing the government to have to step in and run it directly. In 2009, the state owned East Coast franchise was successful paying £ 1 billion in premium payments to the government. But, in 2015, it was reprivatised, this time run by Virgin. But, even Richard Branson couldn’t work his magic. In 2018 Virgin and Stagecoach walked away returning the service to the state sector once more. And it’s not just the East Coast franchise which failed in the private sector but Welsh railways, Northern and ScotRail to name but a few. The state-owned LNER has seen a rapid recovery from the pandemic decline. outperforming the privately run West Coast main line.

Politicisation of the railways

One of the paradoxes of the partial privatisation, it has made the railways more political than the days of British Rail. We see more government intervention in the railways than the pre-privatisation structure. Already, 40% of passenger journey are effectively run by state owned companies and the infrastructure owned by the state controlled Network Rail.

One problem for the UK rail network is the rise in costs. The McNulty report argues UK railways are 34% more expensive than European counterparts. One reason is that relatively short franchises gave little incentive for companies to invest in training staff or investing for long-term. This contrasts to say the Dutch model of competitive tendering, which helped to reduce costs. The implication of rising costs has been an increase in state subsidies. In 2018-19 net government support for the railways was £7 bn, double in real terms, pre-privatisation. However, the Covid collapse in passengers saw government costs soar. Between April 2020 and March 2023, the rail system cost the public purse more than £52bn.

Given the huge level of state support, the profitability of private companies is controversial. For example, in the year ending 2022-23, rolling stock companies paid out £410m to shareholders as profit margins rose 41%. The ownership of the rolling stock is the most profitable part of the network. And this is one criticism of the privatisation structure is that there is a cherry-picking of profitable parts of the network, with the government and taxpayer footing the bill, when the market conditions fail. The RMT claim leakages from privatisation in terms of dividends and admin costs amount to £1.2 billion a year. The Grant-Schapps plan for British Rail, claims there is potential £1.5 billion a year potential savings.

The profitability of railways is disputed. Full Fact claim that profit margins for train operating companies runs closer to 4%. If that is the case, renationalisation of railways will not be the panacea leading of lower prices.

Ticket Prices

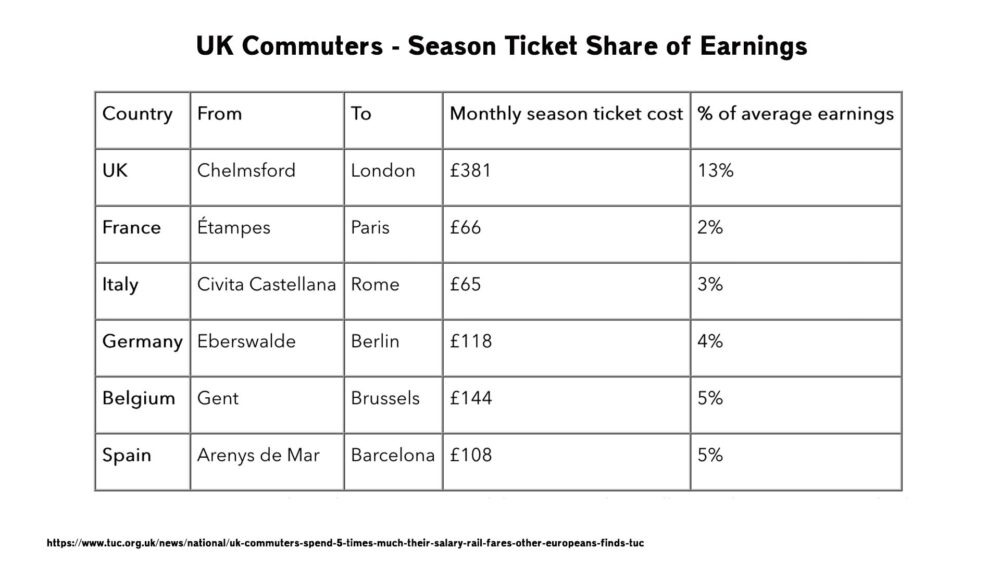

Whilst passengers see rising prices, how does the UK compare internationally? If you use basic buy on the day tickets, UK prices are undoutedly the highest in Europe. However, privatisation has encouraged more complex dynamic pricing with substantially lower prices for buying in advance. The motto of UK trains is buy in advance. If we measure tickets bought in advance, the results are less significant witht the UK less of an outlier. However, if we look at the share of income spent on commuter season tickets, the UK again experiences the highest share.

Whatever the price of UK tickets, customers agree it can be complicated and bewildering to buy the cheapest tickets, and this highlights an issue behind the fragmented nature of the private network, a lack of overall national co-ordination and strategy. For all its faults, British Rail could see the overall picture of the whole rail system. Post privatisation there has been an increase in complexity and fragmentation, with responsibility often lacking. The system has also become very bureaucratic. This was seen in the Hatfield crash of 2000, but also the timetabling disaster of 2018, when trains just didn’t turn up. Network Rail blamed train operating companies. Companies blamed Network Rail and everyone blamed the Rail minister Chris Grayling who claimed it was nothing to do with him. Privatisation created a circular chain of passing the buck.

Successes of Privatisation

One of the few successes of privatisation has been in freight. Freight travel has increased 80% since 1993 but also it has seen costs fall. A reflection that competition has been easier to introduce in national freight, but not passenger services. Also, despite all the problems of privatisation, the UK is one of the few countries to see new lines and routes being added. Chiltern Railways reopened a new route from Oxford to London and has received praise for the quality of its services.

HS2

The cause of rail privatisation has not been helped by HS2, a large ambitious project which has taken a large share of government rail investment, but with its recent part cancellation, is likely to give relatively low returns. The railway writer Christain Woolmar points out that there were many small scale, regional projects which could have given a much higher return and helped reduce costs, for example, increased electrification of lines. By comparison, the state owned India Rail has electrified 45% of its network in just five years, whilst UK electrification runs at a snail pace and incurs high costs. It reflects a general problem that it is just very expensive to build infrastructure in the UK.

There is a good reason why rail privatisation was left to the last. It is the most difficult. Like water, it is an important public service, a natural monopoly and requires significant investment. Whilst increasing competition could play a role, the way the UK was privatised, we ended up with little competition but many of the costs from private monopolies. It’s no surprise no-one followed the UK model. T

Related

Sources:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U6V-HDbX9A8

https://gbrtt.co.uk/keep-informed/blogs/beesley-lecture/

https://www.ft.com/content/d6683d7c-717c-4213-bc06-56c18bb538e5

https://www.seat61.com/uk-europe-train-fares-comparison.html

https://www.christianwolmar.co.uk/2023/05/the-crumbling-edifice-of-rail-privatisation/

- CC BY-SA 2.0view terms

- File:An LNER Azuma train at Burnmouth, geograph 6350005 by Walter Baxter.jpg