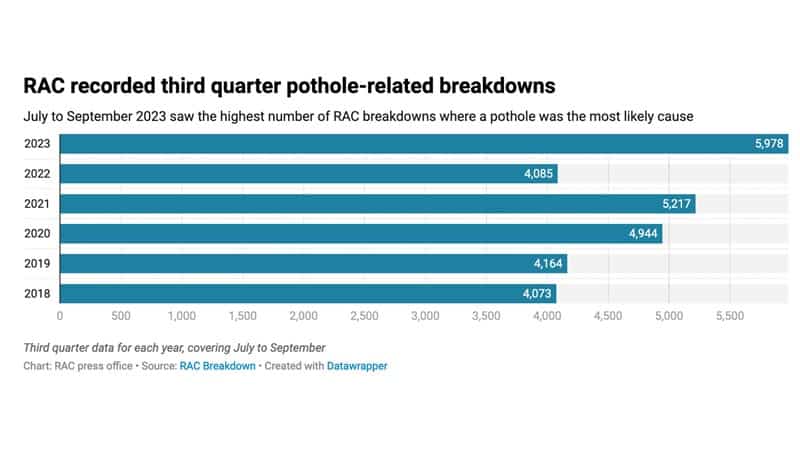

In the past 15 years, there is a general sense that many public services have been deteriorating. This isn’t just pessimism but backed up by longer waiting lists, crumbling infrastructure, even a record number of potholes. But this fiscal blackhole is likely to get worse before it gets better.

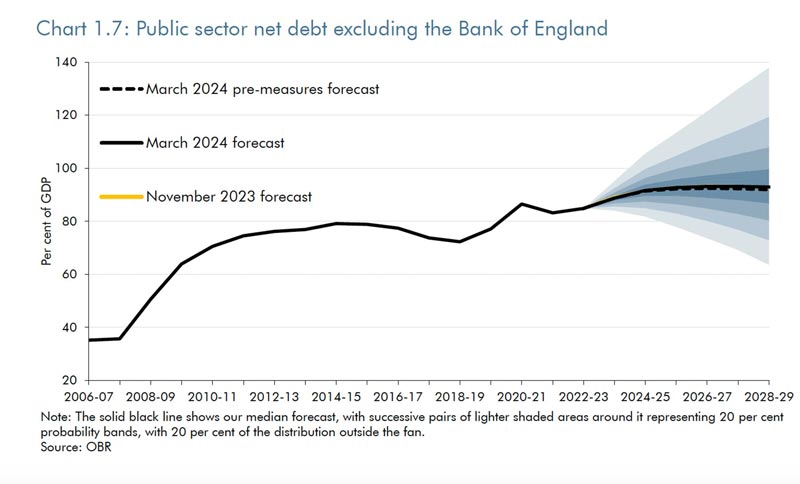

The next government, faces dealing with bankrupt local councils, falling tax revenues, unwinding QE, an ageing population and the fact the most unpalatable spending cuts and tax rises have been left to after the election. It’s not all doom and gloom, there are some mitigating policies we can look at it. But, even taking an optimistic view, the UK is in a grim financial situation that will make it very difficult for the next government.

Spending plans

The first factor is future spending plans. As Ben Zaranko, of the IFS notes “The government’s tendency is to announce pleasant things in the short term to be ‘paid for’ by unpleasant things that conveniently fall after the election,” For example, UK debt rules are met by promising to raise petrol and income tax thresholds. The government is also committed to a strict spending limit but without saying how it will be achieved. Some areas like health, defence and pension are protected, but it means that unprotected departments face real cuts of up to 13%.

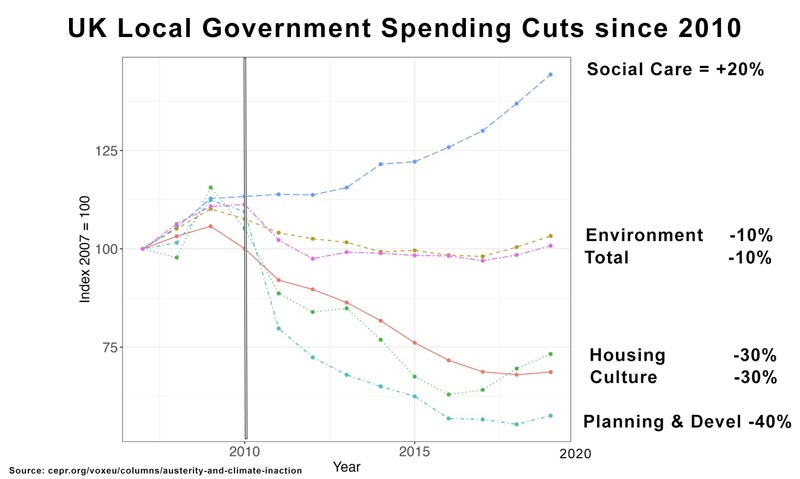

But, this would be on top of austerity for the past decade. Since 2010, local government spending on culture, housing and planning have already been cut by over 30%. The head of the OBR recently referred to government plans as fiscal fiction because there is no detail how cuts will be achieved. Also, when we talk about spending cuts, it’s important to look at per capita spending. With a growing population, spending will have to rise in real terms, just to maintain the same per capita levels. You can see the contrast between GDP and GDP per capita growth in recent years.

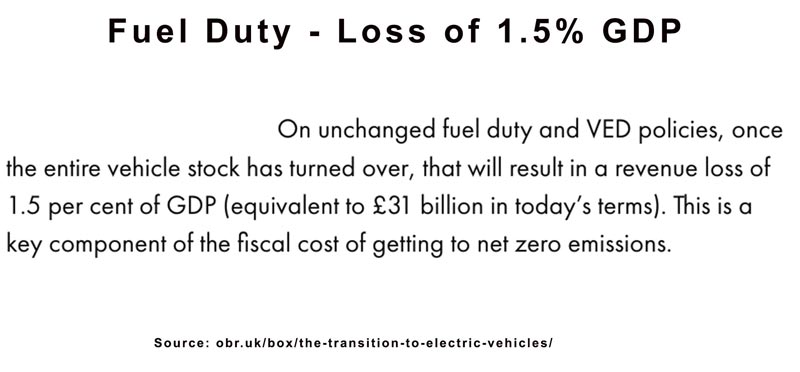

Falling Tax Revenues

Whilst demand for government spending rises, some tax revenues are falling. Fuel duty used to be a big source of revenue, but its continued freezing, plus switch to electric means future governments will steadily lose this source of revenue. The OBR states this will be equivalent to losing 1.5% of GDP in tax revenue by 2030. To put that in context that’s a 6p increase in the basic rate of income tax to compensate lost fuel duty.

If smoking is phased out, that will be another loss of tax revenue. Whilst it’s easy to cut taxes, it’s not easy to introduce new ones. Electronic road pricing is an alternative revenue source, but good luck introducing it. There’s certainly nothing left to privatise which in the past boosted revenues by over £70bn.

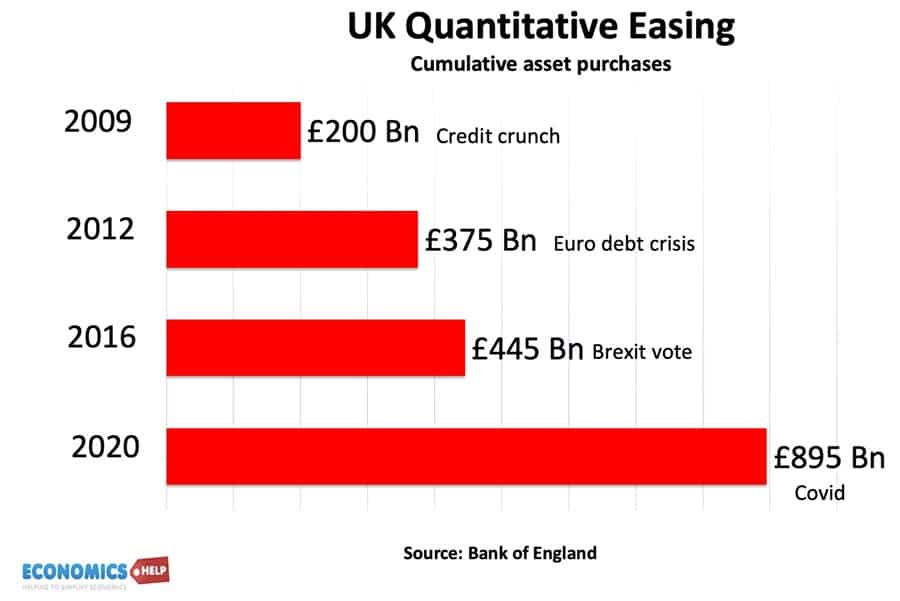

The Cost of QE

A very different problem is QE. It began in 2009. The Bank of England created money and bought bonds. Initially, this made a profit for the Bank and therefore the government. The Bank of England gained interest on the long-term bonds it bought and for a time paid no interest on the reserves it created. However, that has changed. Since the rise in interest rates, the Bank of England has to pay a higher interest rate to commercial banks on the reserves it created.

The New Economics Foundation (NEF) calculate that the Bank of England will need to pay out £150bn by 2028 so they can make payments to the banking sector. But, there is also another problem – the Bank of England bought bonds when yields were low and prices high, but since the rise in interest rates, the bond price has fallen. Effectively the bank bought high and is selling at a loss. What this means is that in the austerity years of the 2010s, the government was actually getting a financial bonus from quantitative easing. But, now the taxpayer is losing out because quantitative easing is operating at a loss. This is a hidden burden on the next government. But, as I promised its not all doom and gloom. There is no reason the Central Bank have to keep paying high interest on all the reserves it created. Why should commercial banks get an effective taxpayer subsidy just because of monetary policy? The ECB has moved to a tiered reserves system, and the UK could do the same, saving a potential £1.3bn to £11bn a year.

Spending cuts does not mean lower spending

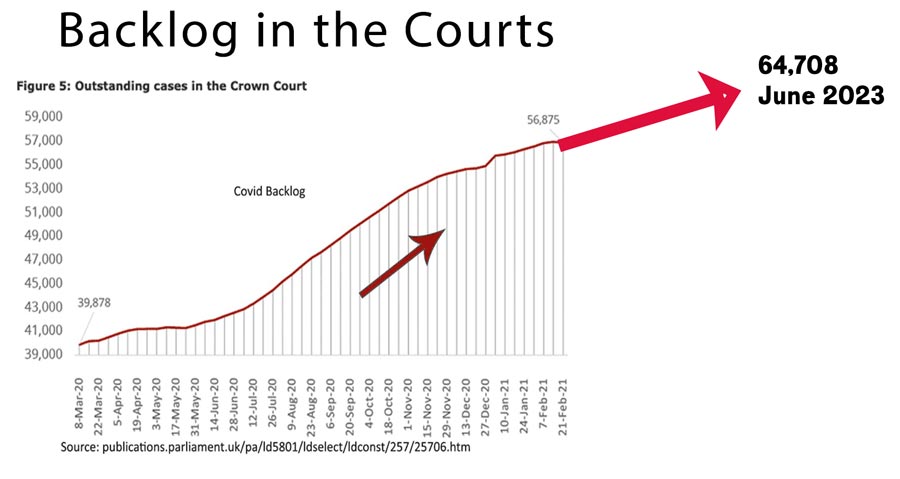

Austerity has been very real for departments like police, local councils, justice and housing. But, deep spending cuts do not necessarily mean lower spending. Potholes increase spending on car maintenance, lack of doctors and health infrastructure can lead to lower labour market participation. The IFS highlight one example of a false economy. To meet spending cuts, many police stations were closed, but this led to an increase in crime, social problems and lower prices. The author of the study claims, that for every £1 of saving, the policy delivered an additional cost of £3 to £7 borne by society. The problem is that UK public services have been under pressure for over a decade. We have seen the closure of 800 libraries since 2010. Waiting times for court cases have risen to record levels.

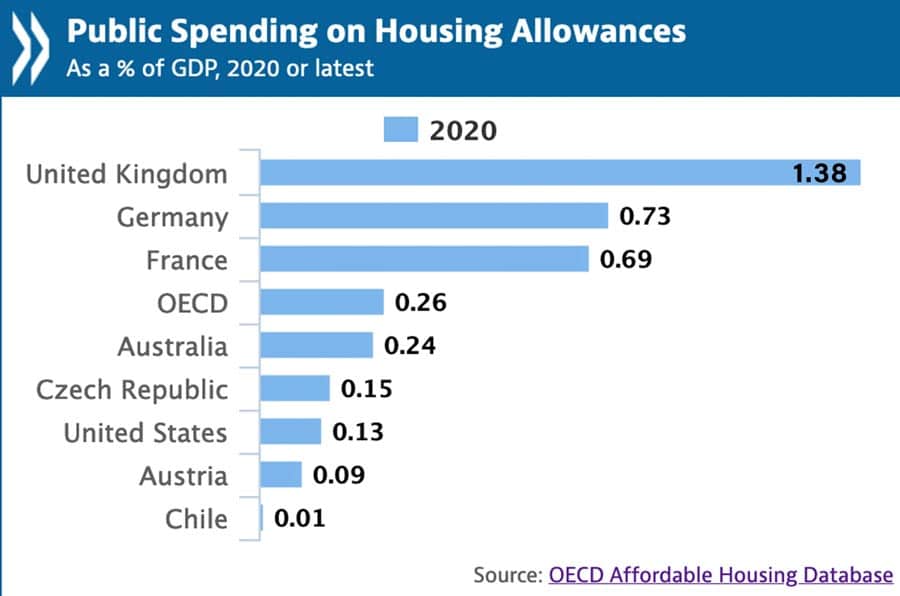

Housing False Economy

Another example of how spending cuts can increase need for government spending. Cuts to public spending on housing has led to a sharp rise in rents and the cost of living. This caused a rise in housing benefit. It rose to £25bn a year. But, the government felt this was too high and so housing benefit was frozen. However, for many households, especially with more than two children, the benefit freezes during a period of rapid inflation meant they struggled to pay the rent.

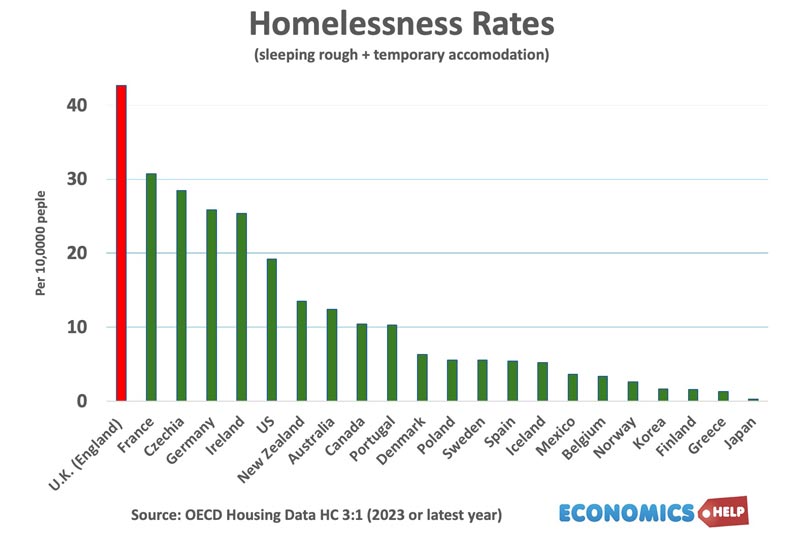

This has led to a surge in homelessness. The UK has the worst rate of homelessness in the OECD This measure is not sleeping rough on a street, but the experience of temporary accommodation. The Local Governments Council claims it cost councils at least £1.7bn to provide temporary accommodation in 2022/23.

Ageing population

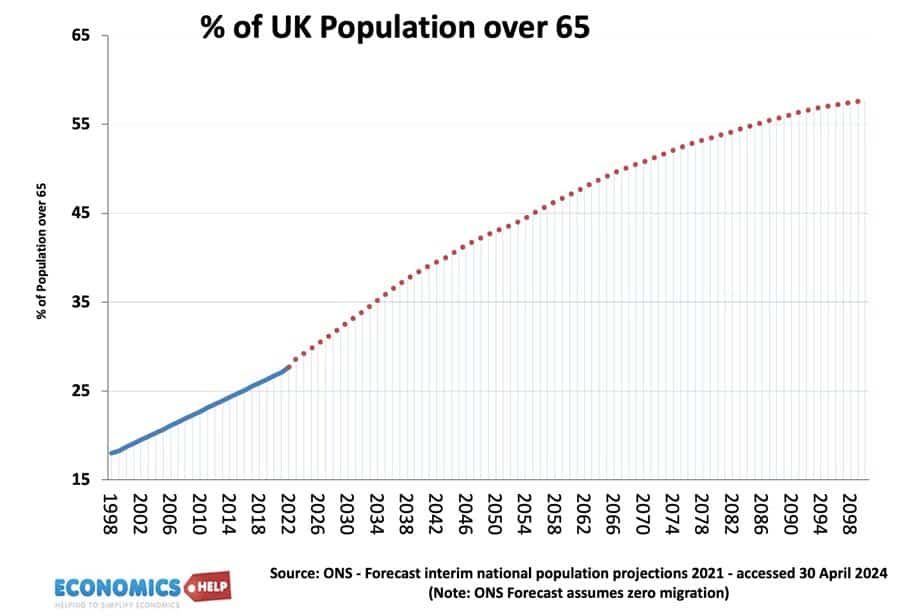

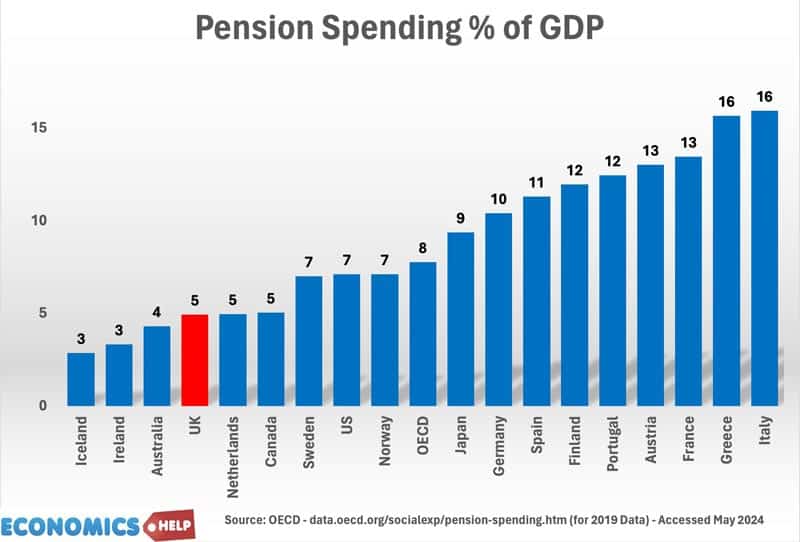

The UK population is ageing. ONS forecast state the share of the population over 65 is forecast to rise to 32% by the end of the decade and then keep rising. The government has raised the pension age to 66 and will increase to 67 around 2027, but even so pension spending has been rising and is forecast to rise. It’s basic economics that an ageing population will increase pressure on health spending, social care and pension, whilst receiving less tax revenue. The triple lock guarantee has meant that pension benefits has risen faster than other benefits. The impact is future governments will face greater spending constraints because of this ageing population. It is worth bearing in mind, that the UK spends a relatively smaller share of GDP on pension benefits than countries like France and Italy, therefore, there is no easy way to reduce the pension burden without increasing the pension burden.

There are some things the government can do, cutting NI and increasing income tax has actually shifted more tax burden onto richer pensioners. The easiest way to get out of this fiscal hole of ageing population is to raise the retirement age to 70. Some claim this is necessary. It would certainly improve finances. But, it is worth bearing in mind, we have increased inequality of healthy life expectancy. A rise in the retirement age to 70 would be very hard for lower sociel-economic groups with poor health. The other solution is immigration. ONS forecasts actually assume zero net migration, I’m not sure why they chose this. But, migration of working age adults, especially those willing to work in health and social care would limit the costs.

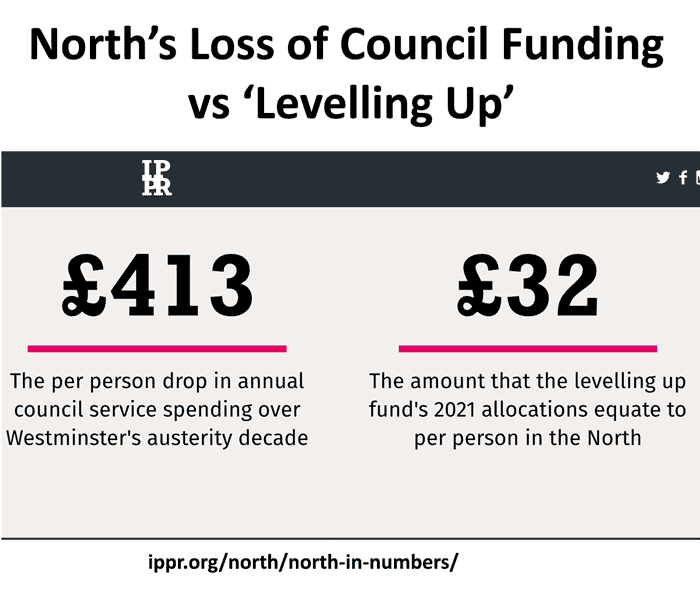

Levelling up

For all the talk of levelling up, the real story is that local government spending has been squeezed by central government cuts. Cuts to local spending dwarf levelling up funds. Local government is an unprotected department and faces more upcoming cuts. It has been the most visible sign of austerity. The RAC reported a record rise in pothole related breakdowns.

An estimated 1 million in the UK. Local councils don’t have the budget. 800 Libraries closed down since 2010.

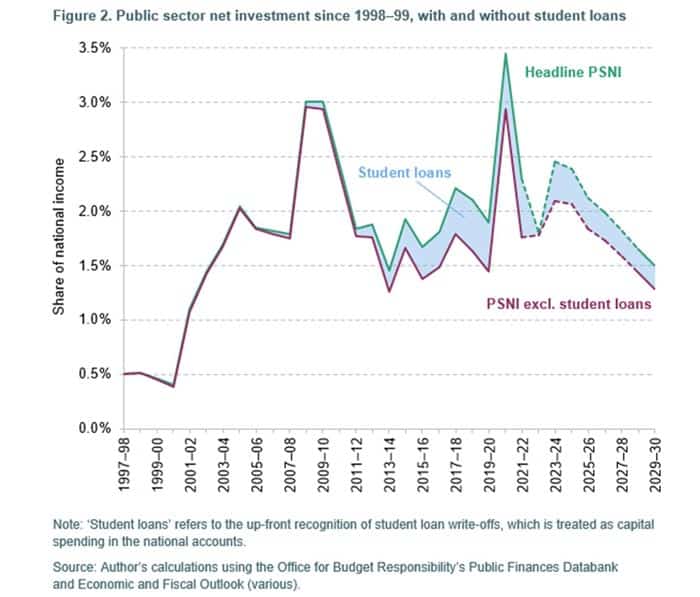

Public investment

Despite deteriorating public servers, public investment is set to fall. Something I learnt recently was that figures for public investment include student loans that have been written off. But, student loans is not recently public investment. The problem is that there are many candidated for public investment. Water faces renationalisation and the need for more investment. It’s a similar story in railways and housing.

Sources: