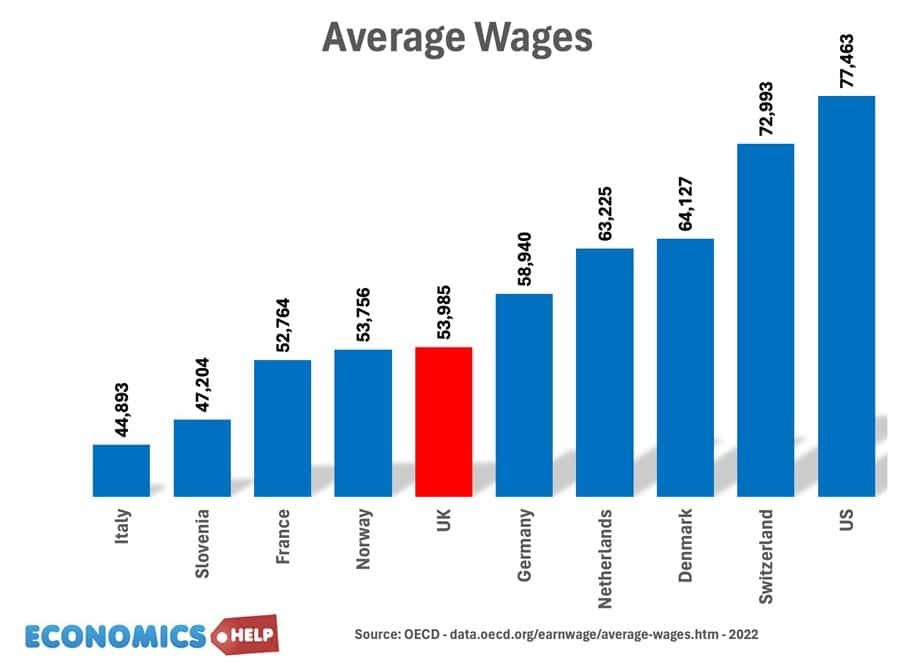

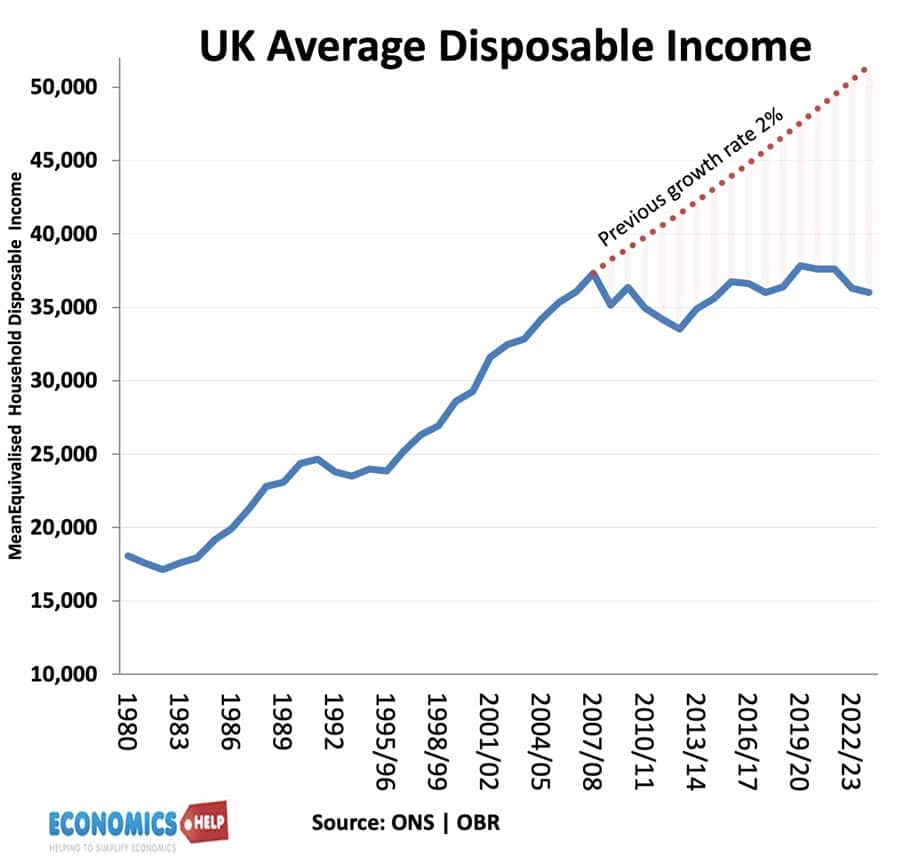

Compared to many major European economies, UK average wages are lower and this is before we take into account relatively higher housing costs and longer working hours for British workers. In the past 15 years, the UK has seen pretty much stagnant real wages. If the pre-crisis trend had been maintained, real wages would be £11,000 a year higher. Apart from Italy, relative to other European countries, UK wages have fallen behind, meaning on current trends, UK wages could slip behind more countries in the future.

The UK Treasury like to point out that since 2010, UK real GDP compares relatively well to other European economies. Newspapers report the UK economy is going gangbusters. But if this is a true reflection of the UK economy, why has wage growth for the past 15 years been such a disaster? Let us look at why UK wages have disappointed and whether there is any hope it will improve in the coming years.

Firstly, let’s quickly address the real GDP issue. UK Real GDP growth has averaged 1% since the great financial crisis, this way below the post-war trend rate, but importantly, has been significantly boosted by immigration and a growing population. Real GDP per capita gives a better guide to what the average citizen experiences. On this metric, the UK performance is relatively weak. The UK is still below the 2019 level. Now the last GDP statistics were a bit more positive, but before we talk about the economy doing really well, we have to put one quarter’s growth in the context of the past 15 years. It’s one of the worst Parliaments for wage growth. To regain the post-war trend in rising wages would take several years of positive growth.

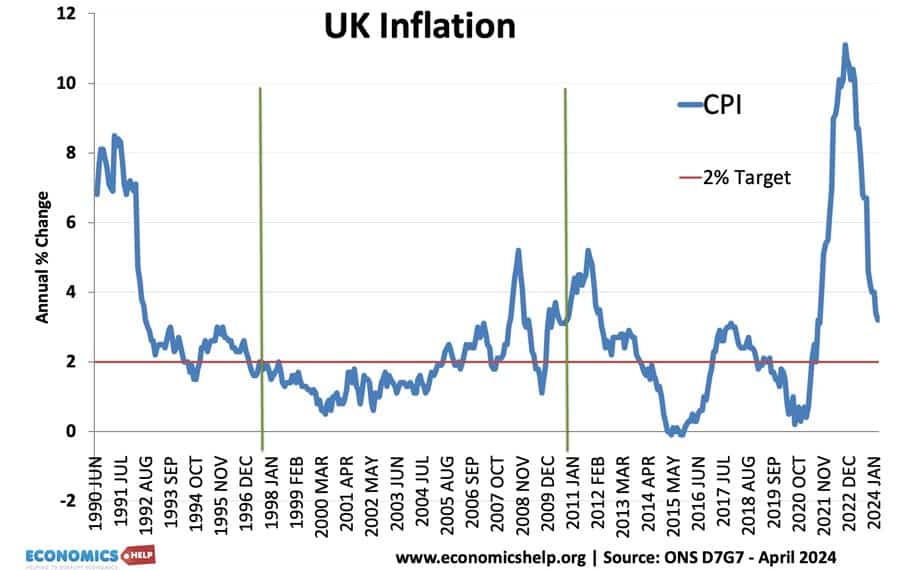

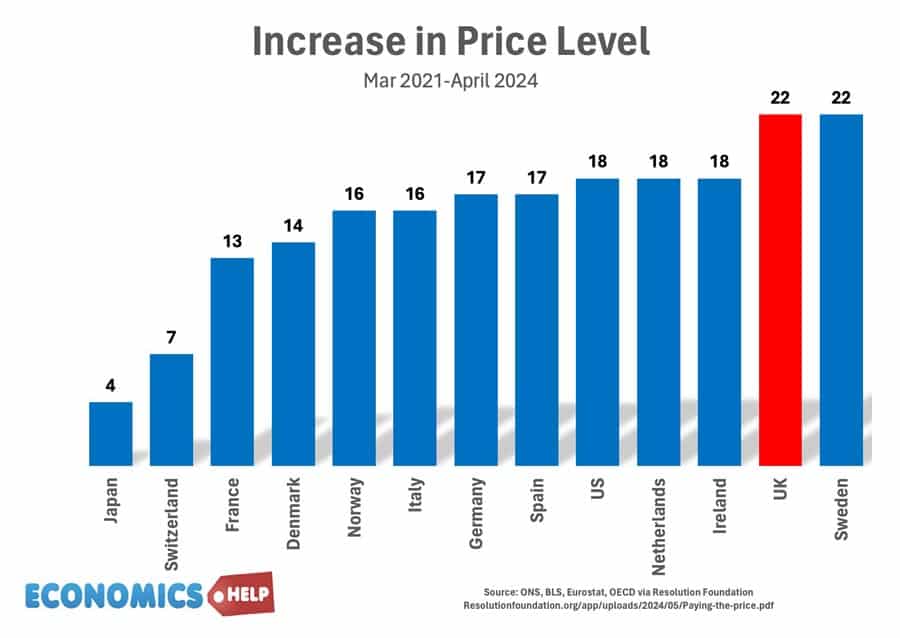

The biggest hit to real wages in the past two years has been from inflation. Inflation was a global story, with rising gas and oil prices pushing up prices. However, UK prices have risen significantly more than other countries. 22% rise compared to 13% for France.

And also it is inflation which impacted low income groups relatively more. The biggest price rises were in essentials like food, which saw 40% rise in prices, and interestingly we saw a 7% fall in consumption on food. No wonder demand for food banks has soared in the past few years. But this raises the important question why has the UK been more affected by inflation?

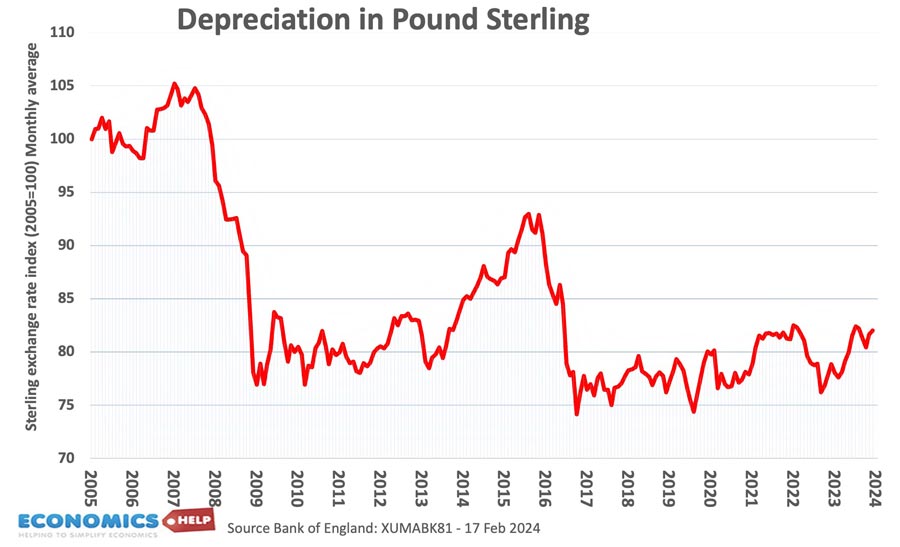

In 2016, the Pound fell 15%, which raised import prices directly. However, in the past three years, the Pound has stabilised so this does not explain the recent rise in prices?

Another potential reason is monopoly firms taking advantage of inflation to push up prices, now whilst there is evidence firms did this at the start of Covid, in the past year, UK profit margins have fallen quite sharply, showing it’s not just workers who have received lower returns. The squeeze is also being felt in corporate profit margins.

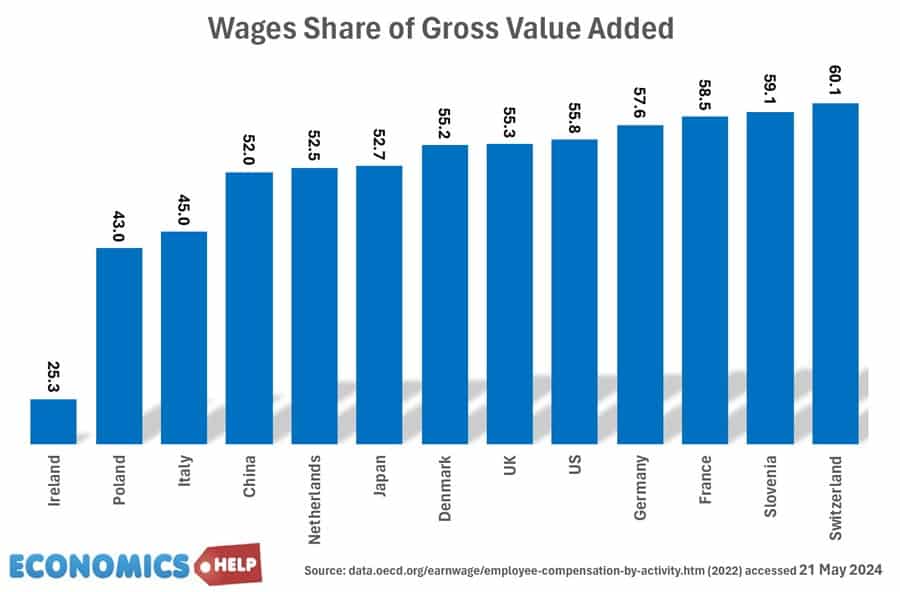

UK wages account for 55% of Gross Value Added which is actually quite a high percentage compared to other countries.

So what was behind the UK’s sensitivity to inflation?

Firstly, the UK’s reliance on natural gas had a big impact, with electricity prices rising fast. In France, prices rose 40% less than the UK reflecting a much more generous government price cap and greater availability of nuclear energy. Secondly, Brexit related frictions have pushed up prices of transport and food imports, with the UK experiencing shortages, delays and higher costs. Researchers at LSE claim Brexit has caused food prices to be 30% higher or 8 percentage points higher than without Brexit. It was a global inflation shock, but these frictions added to the price rises. But the bad news is that far from getting better new custom checks and charges are being introduced this year and could add another 60% to costs for food importing. One firm importing goods from eastern Europe claims it could have to pay up to £2,000 more per lorry. This will feed through into higher prices.

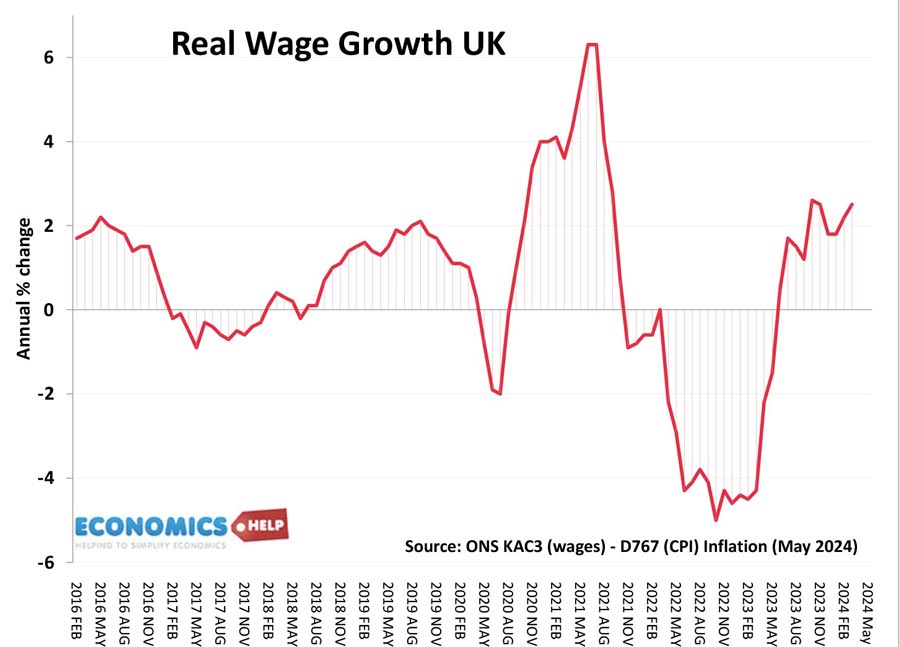

However, whilst the past few years have been difficult, it is only part of the story, why have wages nearly stagnated since 2008? To explain this we need to look more into the underlying weakness of the UK economy.

But first, it is worth pointing out that not all workers have been equally affected. The worst hit sector is public sector workers. For example, NHS staff have seen a fall in real wages of 6%. This decline in public sector pay has led to a crisis of recruitment and low morale and a reflection of government austerity, with public sector pay a frequent target of government austerity. On this front with more spending cuts planned for future years, it will be hard to reverse this. There is no sign of a better government fiscal position to boost wages. If anything the situation is worse than it looks. Usually, a period of inflation like we saw in 2022 helps to reduce debt to GDP. This is because inflation can help inflate away the government’s debt with higher nominal tax revenues. But, that hasn’t happened, debt has increased in recent years. It’s not just workers being squeezed but government finances too.

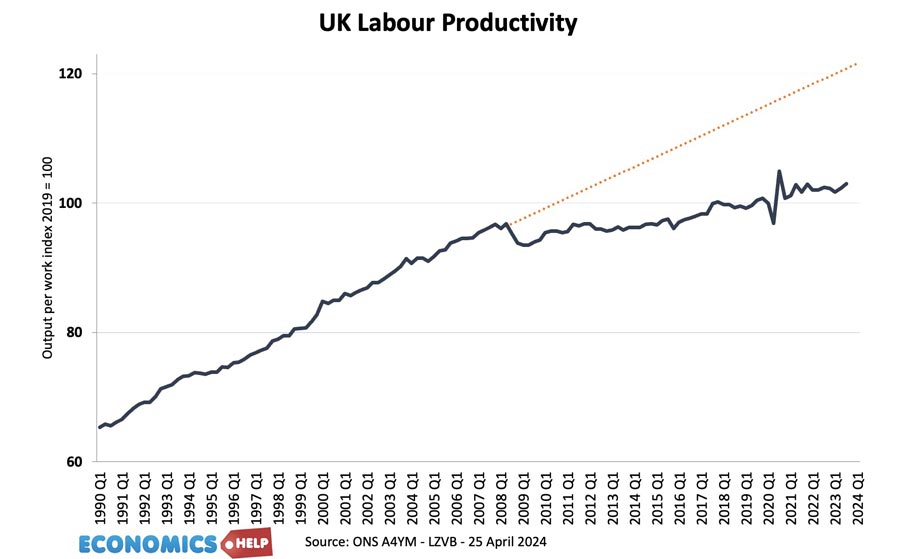

The biggest long-term factor determining wage growth is labour productivity. In fact, producitivity also determines other factors like profit, economic growth and government finances. Basically, if workers become more productive, wages tend to rise. But, the problem here is that productivity growth has slowed down dramatically. It explains why one of the few countries to have worse wage growth than the UK, Italy, has had a productivity nightmare in the past 20 years. The fear is that the UK is starting to resemble the 20-year wage stagnation of Italy.

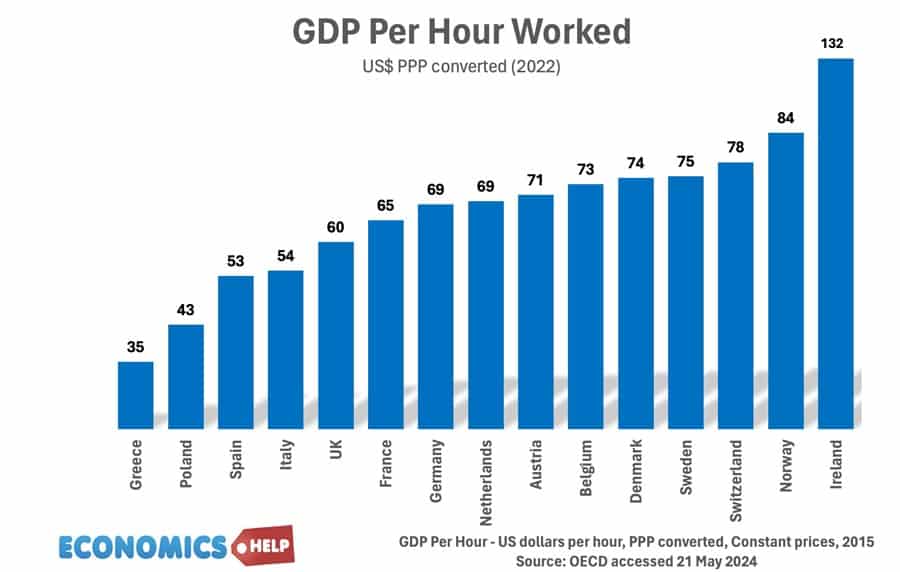

How long do you need to work for your wage?

Another factor behind wages, is that it also depends how long you have to work.

This shows output per hour worked measured in PPP terms. The UK’s economy is around 15% below that of Germany and Netherlands. In effect, UK workers have to work longer hours to produce the same output as German workers. Unless, productivity rises, there is little hope of sustained rises in real wages. In the past decade there have been frequent forecasts productivity would regain its upward momentum, but the problem with these forecasts is that they are overly optimistic.

Any postitive news for real wages?

At least in the short-term, there is some good news. Headline inflation is falling fast. And whilst inflation falls, workers are finally seeing growth in real wages. This has to be kept in the context of 15 years of stagnant wages, but it is still good news. Secondly, the period of high inflation and high interest rates did encourage greater saving and paying off of debts. UK personal debt levels are certainly better than pre 2008. It means that as inflation falls and possibly interest rates later in the year, consumers may become tempted to increase spending and help the economic recovery. This is significant for real wage growth. However, whilst there is this more optimistic outlook in the short-term, whether this will translate into better long-term growth is much more uncertain.

The only positive trend in the past 15 years has been the lowest-paid workers gaining higher wages through the minimum wage, but this alone can’t reverse the UK’s relatively high level of inequality. Outside London and the poorest households are significantly worse off than the poorest households in other countries such as France.