Since 2000, there was only one major economy which has seen a fall in real GDP per capita – Italy. In this period, Italy has experienced a shocking fall in productivity, rising debt, and prolonged economic turmoil. We are told the Italian economy is riven by cronyism, falling birth rates, and a regional divide. Yet, to many people’s surprise, one of the fastest growing economies since 2019 has been Italy.

Is this rebound of economic growth the start of a new era for Italy or is it just papering over the long-term cracks?

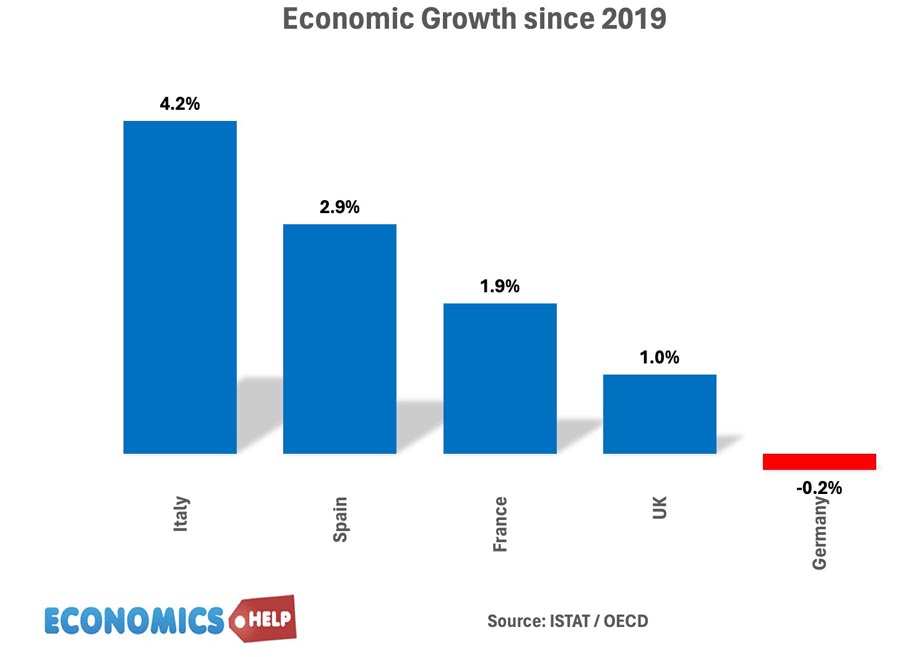

There are three reasons for the recent higher growth in Italy. Firstly Italy received €110bn of EU funds as part of the Covid recovery plan. By 2026 it will receive €195 the largest amount in the EU. Secondly, the government have pursued generous tax credits to subsidise home improvements known as the Superbonus 110%. It has led to a surge in housing investment and this has caused much of the higher growth. By February 2024, government support had contributed upwards of €200bn new investment or 10% of Italy’s GDP. But, given such a large fiscal stimulus, Italy’s growth since 2019 at 4.2% is not particularly spectacular. We are not so much seeing an Italian economic miracle but continued weakness in the European economy and Germany in particular. And given the interconnectedness between Italy and Germany, a recession in German manufacturing will inevitably filter through to Italy. This year, the Bank of Italy expects growth of 0.5% whilst Germany will contract by 0.2%. But, 0.5% is still very low

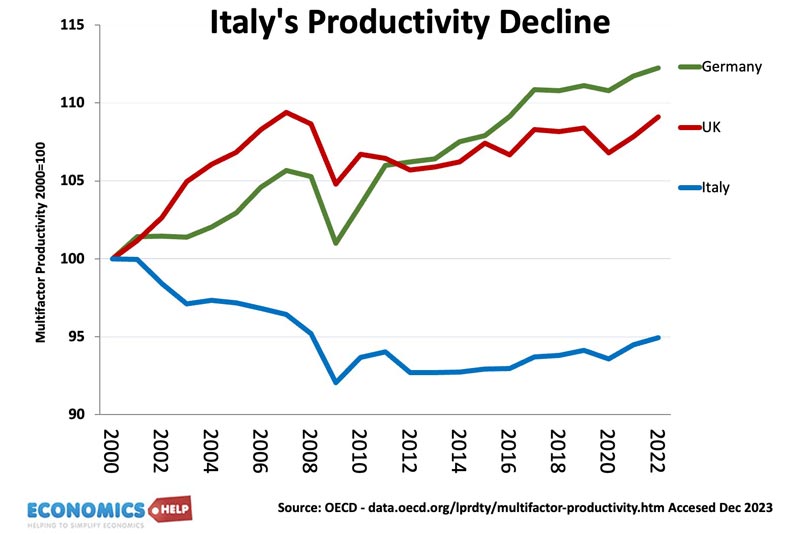

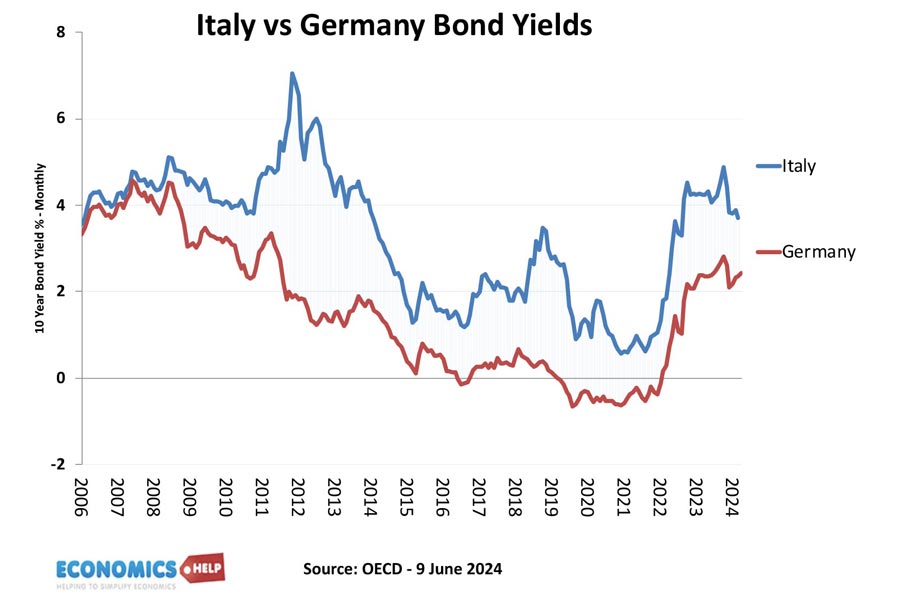

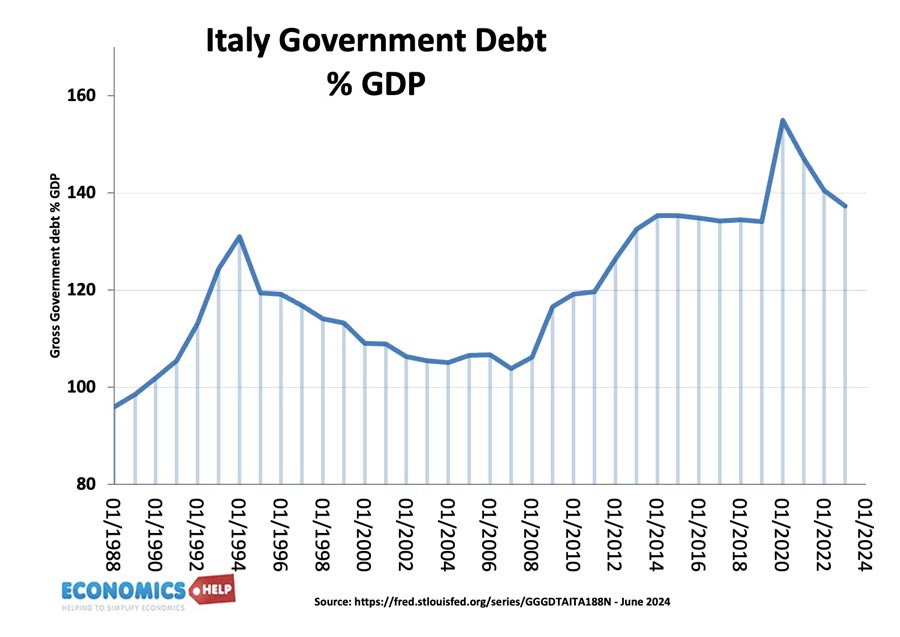

Also, whilst the stimulus boosted growth in the short-term, the key question is whether it will help to tackle the underlying productivity crisis hitting the Italian economy. Since 2000, Italy’s productivity, the output per worker has slumped behind other competitors. Another problem of the fiscal stimulus is that it has led to a budget deficit of 7.4% of GDP – double the EU average. This is a concern given Italy’s long history of high debt. Italy is paying a calamatous 8.2% of revenue in debt interest payments. Adding to debt through fiscal stimulus will increase these costs in the long-term. However, there are two pieces of good news. Italian bond yields have come down closer to German levels.

This is due to both low inflation and market predictions the Eurozone is slowly moving towards a common bond market.

Secondly, despite fiscal stimulus, the high levels of Italian debt have also fallen from 155 to 137% of GDP. It is still one of the highest in the developed world, but at least moving in the right direction. However, it does limit Italy’s ability to continuously promote economic growth through fiscal stimulus. The fall in debt, partly reflects the fact that with higher economic growth, tax revenues at last are starting to rise. And this leads onto a factor which really hobbled the Italian economy in the 2010s.

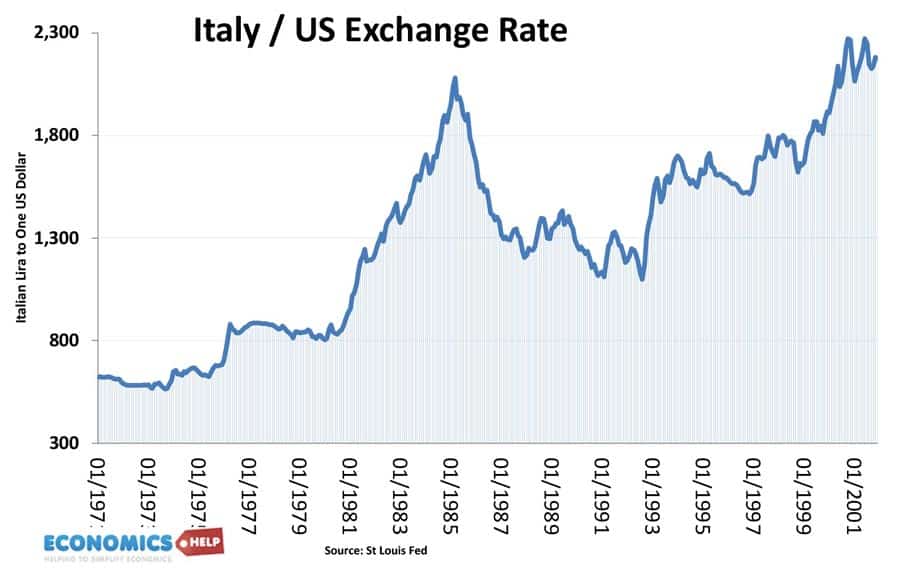

After the financial crisis the Italian economy had a double dip recession. The first recession was caused by the global credit crisis, the second was more self-inflicted as membership of the Eurozone and surging bond yields caused Italy to pursue spending cuts and austerity in the time of economic slowdown. At least Italy seems to be learning that austerity in a recession only makes things worse. However, there is more to Italy’s stagnation than austerity. The slowdown started in 2000, just as Italy happened to enter in the Euro. Some claim this is co-incidence, but there is more to it than that. In the post-war period, Italian inflation was often higher than other European countries, to maintain competitiveness, Italy relied on frequent devaluations in the Lira.

However, once in the Euro, this easier option was not available. Italy had falling productivity, higher costs, but without the ability to devalue, they just become less competitive and manufacturing struggled this led to a record current account deficit, lower growth and a build up of debt as imports were financed by borrowing. Not only that but in the Euro, Italy lost control of monetary policy and bond yields soared.

The good news is that Italy is starting to adjust to the Eurozone, after 20 years in the Euro, it knows it can’t rely on devaluation and high inflation. And one of its recent successes is keeping inflation relatively lower than many other countries. This is despite a reliance on natural gas and being hard hit by Ukraine War. Italy faced some of the highest wholesale costs of electricity in Europe. But, consumers have been insulated by a highly regulated electricity market. Prices fell 10% last year and are likely to fall 20% this year.

Long-Term Problems

However, what about all the long-term problems of the Italian economy have these been resolved by recent period of economic growth?

Economist Bruno Pellegrino, argues a factor behind Italy’s decline is its tendency to nepotism and cronyism, which has led to poor quality management. An NBER paper argues that Italian often firms rely on cronyism and family connections rather than meritocracy. This leads to an inflexibility and lack of dynamism and a key factor behind low growth. Italy has the second largest manufacturing sector in Europe, but the global economy is fast changing, anbd has struggled to respond to the influx of cheap Chinese imports and now US led subsidies. It also has a higher percentage of small firms, who are getting left behind, especially in IT.

Another factor, which undoubtedly contributed to low growth was the political turmoil, especially of the Bresluconi era where government was sidetracked by scandals and votes of no-confidence. Italy has had 68 governments in 77 years, making it hard to introduce long-term reforms which promote real economic growth. There are some signs of improvements in stability in recent months.

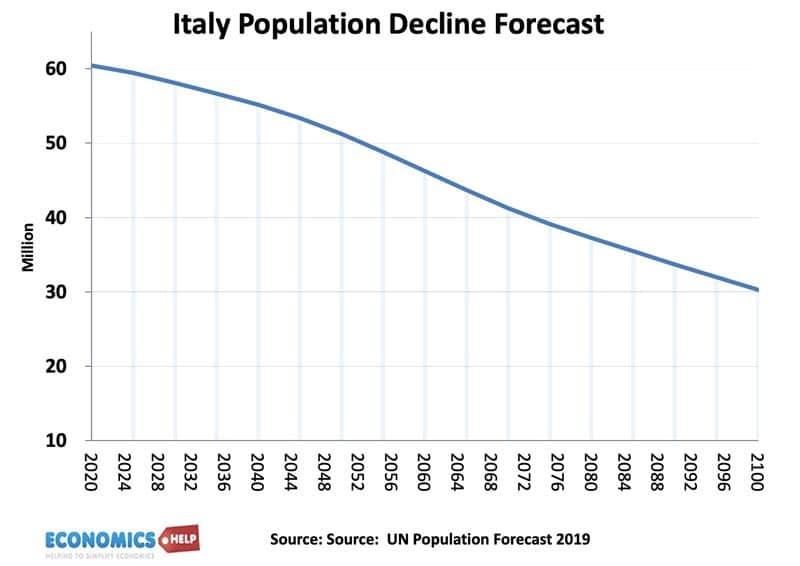

Another long-term issue facing Italy is a decline in the working age population. Italy has one of the lowest birth rates in the world, and is ageing earlier than other European countries. It faces one of the highest pension burdens in the OECD, 16% of GDP goes on pensions, but this is only likely to grow as more reach retirement. This is a large fiscal burden that is limiting the government’s ability to spend on more productive areas of the economy. Even the fall in unemployment more reflects a shortage of workers than any improvement in the economy.

Not only do Italy have a shrinking base of young workers, they have one of the lowest rates of higher education in Europe. Italy has the 2nd highest rate of young people not in employment, education or training in the EU behind only Romania. The perceived poor quality of higher education deters young people from entering university creating a cycle of lower skills, that prevents upward mobility. In fact, young people are leaving Italy in droves. 10% of highly educated Italians live abroad, the highest rate in the developed world.

Just checking I’m not being shadow banned on your YT site as my comments show but the count doesn’t change.