The Eastern European Boom

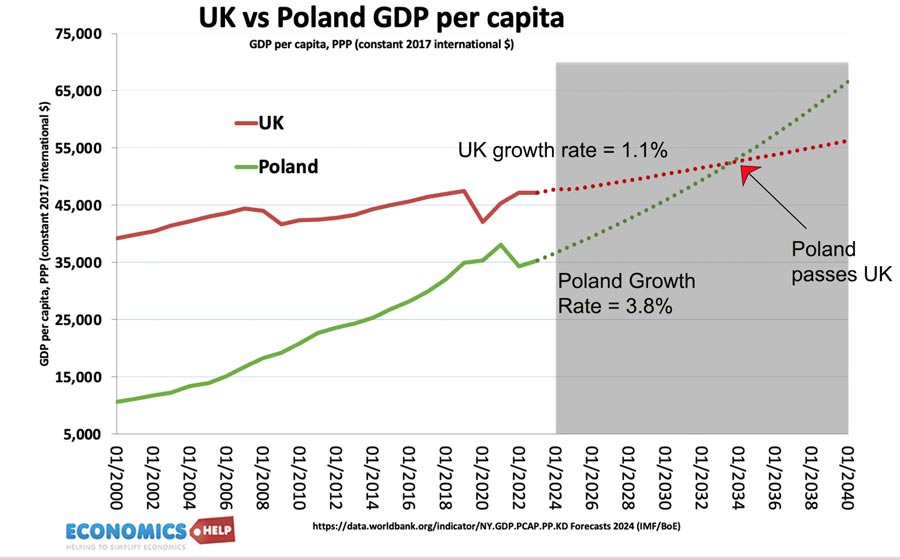

Whilst Western Europe struggles with low growth, Eastern Europe is booming. In the past two decades, Eastern Europe has quietly witnessed an economic transformation, with growth in living standards outperforming the West. Estonia, Poland and Romania have all seen a doubling of living standards and are catching up with their Western peers. In the early 1990s, wages in the west were five times higher than Poland. But on current rates of economic growth, average wages in Poland could overtake the UK towards the end of the 2030s. It’s a remarkable turnaround. Whilst the German car industry stutters, Poland has seen a doubling in the size of car industry, which now accounts for 8% of GDP. What has caused this transformation in the east? and why is the west falling behind?

Reasons for Higher Growth

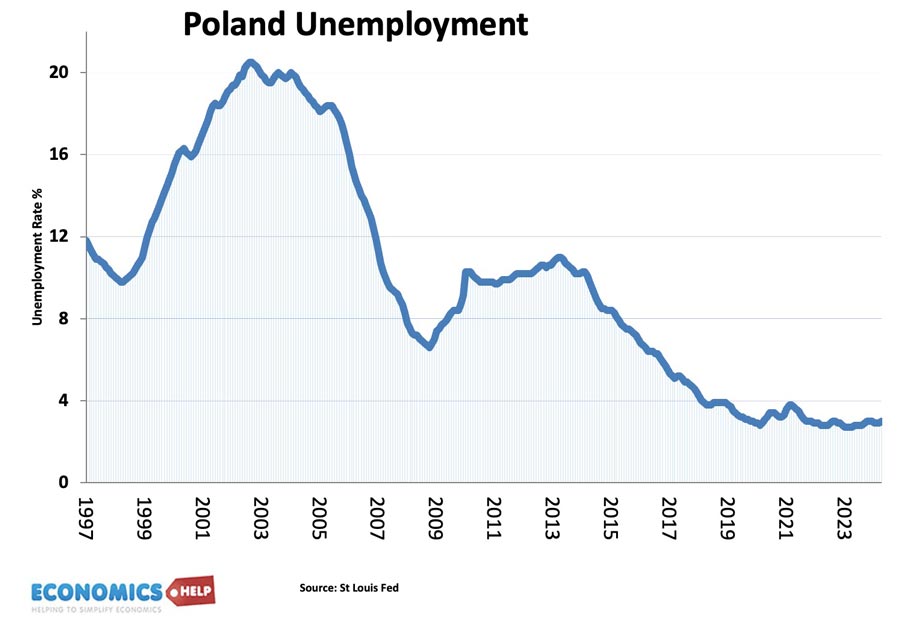

One reason for higher growth rates in eastern Europe is that in the post-communist system, there were many inefficiencies that gave room for easy productivity gains as firms learnt western methods. However, this productivity gap is slowing meaning it will get harder to maintain higher growth rates than the west. 2023 was a difficult year for Polish economy with high inflation curtailing growth. But, since the October elections, renewed confidence in the private sector has seen the World Bank revise upwards its forecast of growth to 3% in 2024 and 3.5% in 2025. This is much more optimistic than the miserable growth rates predicted for the likes of Germany, France and UK.

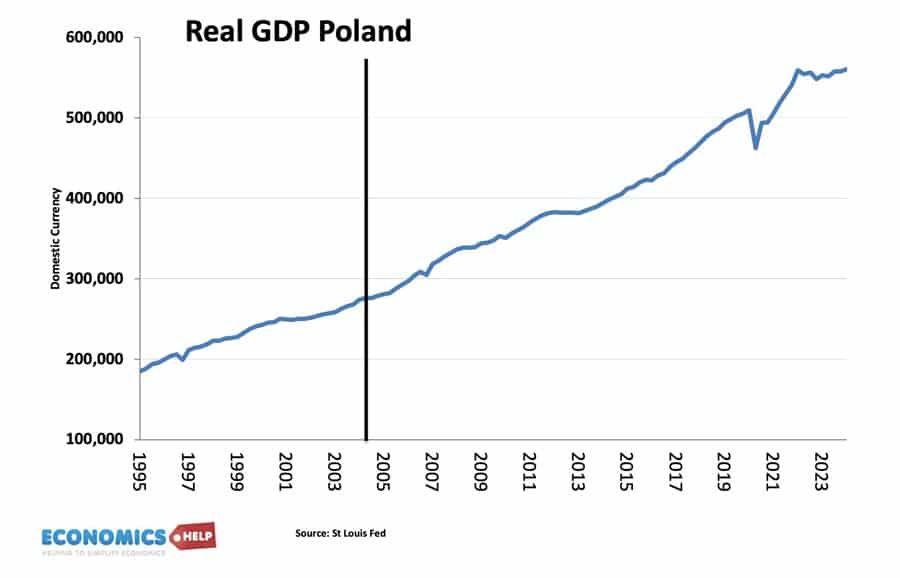

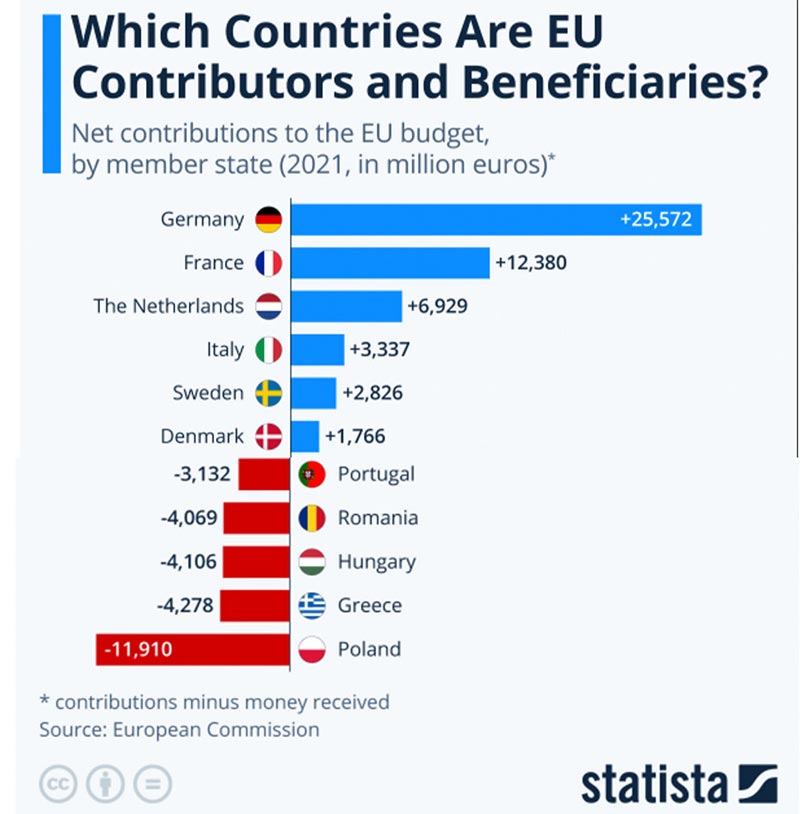

Since joining the EU in 2004, Poland has more than doubled its national output. The success of EU membership explains why support for EU is so high in Poland. Membership of the EU saw three main benefits.

Firstly, trade with Europe increased. Secondly, it became more attractive for foreign investment, and thirdly Poland has been one of the biggest recipient of EU Funds. in 2021, alone it received a net gain of €12bn. In recent years, concerns over judicial independence and rule of law saw the EU place a temporary freeze on funds. But following a restoration of judicial independence under Donald Tusk, EU recovery funds were unfrozen and this will help economy.

Investment

However, more than EU funds, what has really boosted the Polish economy growth is the inflow of private investment as multinational firms see Poland as an attractive destination. The stock of foreign direct investment in Poland reached $415bn in 2018 or 40% of GDP. Poland is the largest recipient of foreign direct investment, but why has Poland attracted so much investment? Firstly, wage costs are still significantly lower than Germany and the UK. Secondly, Poland is one of the hardest working economies in the OECD, an average 1766 hours per year, compared to 1332 in Germany. Poland also has good levels of education with 42% of young workers having higher education, above the European average. Also, since the Ukraine War, raised fears over the west’s reliance on China, Poland is seen as a partial alternative. Lower cost manufacturing but the with the great advantage of geographical proximity.

Inequality

One of the striking features of Polish economic growth is that it has corresponded to a decline in inequality. This shows a 26% decline in levels of inequality, showing that growth has been broad based. In 2005, 45% were at risk of povery, in 2022, that had fallen to 16% In fact, across Eastern Europe, levels of inequality are amongst the lowest in the world. By contrast, Brazil has a GINI coefficient of 50.In the early days of joining the EU, Poland suffered something of a brain drain, with young entrepreneurial workers leaving to seek higher wages in western Europe. In 2011, it reached a record 2 million net emigration. This loss of skilled workers adversely affected the economy, but in recent years, the effect of Brexit in the UK plus narrowing of the wage gap has seen many of these young workers return to Poland and net emigration has declined. Since 2022, Poland has also seen the biggest influx of Ukrainian refugees, bolstering the labour force and GDP, though also putting pressure on housing and education. 41% of the 1 million Ukrainian refugees are of school age. The Ukrainian conflict has hightened tension in eastern Europe and put pressure on Poland’s trade with Russia, but it has also encouraged multinationals to reshore manufacturing closer to Europe rather than more risky supply chains from Asia.

In 2023, partly as a result of mortgage subsidy and partly growing population, Poland saw the fastest growth in house prices in Europe. But, despite recent the recent housing boom, Poland still has one of the more affordable housing markets in Europe, helped by relatively lower population density. Economic growth and rising wealth have fostered a construction boom, which contributes to growth and so far has avoided the worst excesses of the Anglosphere.

Strong economic growth has created a virtuous circle of falling unemployment – close to full employment and relatively low levels of government debt by European standards. This is despite significant government investment, such as a major increase in the road network, a key factor in Poland’s place as a source of trade. Relatively low borrowing meant the recent incoming government had room for fiscal expansion after a difficult 2023.

Potential Problems

The Polish economy is not without problems. It was vulnerable to loss of Russian gas, seeing inflation reach 15% in 2022. In 2023, energy prices rose 23% the 3rd highest in Europe. It may be catching up with western Europe, but the pace of narrowing has slowed, and the narrowing gap reflects as much weakness in western European economies as strength in the Polish economy. Around 28% of Poland’s exports go to Germany, so an economic slowdown in their main trading power and traditional engine of European growth bodes ill for the Polish economy.

Western Europe has struggled in recent years due to ageing population, low investment and low confidence. Germany was particularly affected by rise in gas prices. Also, western Europe a member of the Euro has tended towards fiscal austerity, which has hampered public investment. This is a factor behind Germany’s long-term difficulties. In theory, as a member of the EU, Poland should progress towards adopting the Euro. But, the difficulties faced by countries like Greece, Italy and Portugal may show a cautionary tale. Once in the Euro, countries lose independence over monetary policy and exchange rate. There is no guarantee that interest rates set in Frankfurt would be ideally suited to a Polish economy that is currently very different to western Europe. However, for the moment, delaying the decision seems to be fine. A key feature for the Polish economy is the outlook for the Germany economy, this video suggests that Germany’s crisis shows no signs of abating and could get worse.